What you need to know about research dissemination

Last updated

5 March 2024

Reviewed by

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

In this article, we'll tell you what you need to know about research dissemination.

- Understanding research dissemination

Research that never gets shared has limited benefits. Research dissemination involves sharing research findings with the relevant audiences so the research’s impact and utility can reach its full potential.

When done effectively, dissemination gets the research into the hands of those it can most positively impact. This may include:

Politicians

Industry professionals

The general public

What it takes to effectively disseminate research will depend greatly on the audience the research is intended for. When planning for research dissemination, it pays to understand some guiding principles and best practices so the right audience can be targeted in the most effective way.

- Core principles of effective dissemination

Effective dissemination of research findings requires careful planning. Before planning can begin, researchers must think about the core principles of research dissemination and how their research and its goals fit into those constructs.

Research dissemination principles can best be described using the 3 Ps of research dissemination.

This pillar of research dissemination is about clarifying the objective. What is the goal of disseminating the information? Is the research meant to:

Persuade policymakers?

Influence public opinion?

Support strategic business decisions?

Contribute to academic discourse?

Knowing the purpose of sharing the information makes it easy to accurately target it and align the language used with the target audience .

The process includes the methods that will be used and the steps taken when it comes time to disseminate the findings. This includes the channels by which the information will be shared, the format it will be shared in, and the timing of the dissemination.

By planning out the process and taking the time to understand the process, researchers will be better prepared and more flexible should changes arise.

The target audience is whom the research is aimed at. Because different audiences require different approaches and language styles, identifying the correct audience is a huge factor in the successful dissemination of findings.

By tailoring the research dissemination to the needs and preferences of a specific audience, researchers increase the chances of the information being received, understood, and used.

- Types of research dissemination

There are many options for researchers to get their findings out to the world. The type of desired dissemination plays a big role in choosing the medium and the tone to take when sharing the information.

Some common types include:

Academic dissemination: Sharing research findings in academic journals, which typically involves a peer-review process.

Policy-oriented dissemination: Creating documents that summarize research findings in a way that's understandable to policymakers.

Public dissemination: Using television and other media outlets to communicate research findings to the public.

Educational dissemination: Developing curricula for education settings that incorporate research findings.

Digital and online dissemination: Using digital platforms to present research findings to a global audience.

Strategic business presentation: Creating a presentation for a business group to use research insights to shape business strategy

- Major components of information dissemination

While the three Ps provide a convenient overview of what needs to be considered when planning research dissemination, they are not a complete picture.

Here’s a more comprehensive list of what goes into the dissemination of research results:

Audience analysis : Identifying the target audience and researching their needs, preferences, and knowledge level so content can be tailored to them.

Content development: Creating the content in a way that accurately reflects the findings and presents them in a way that is relevant to the target audience.

Channel selection: Choosing the channel or channels through which the research will be disseminated and ensuring they align with the preferences and needs of the target audience.

Timing and scheduling: Evaluating factors such as current events, publication schedules, and project milestones to develop a timeline for the dissemination of the findings.

Resource allocation: With the basics mapped out, financial, human, and technological resources can be set aside for the project to facilitate the dissemination process.

Impact assessment and feedback: During the dissemination, methods should be in place to measure how successful the strategy has been in disseminating the information.

Ethical considerations and compliance: Research findings often include sensitive or confidential information. Any legal and ethical guidelines should be followed.

- Crafting a dissemination blueprint

With the three Ps providing a foundation and the components outlined above giving structure to the dissemination, researchers can then dive deeper into the important steps in crafting an impactful and informative presentation.

Let’s take a look at the core steps.

1. Identify your audience

To identify the right audience for research dissemination, researchers must gather as much detail as possible about the different target audience segments.

By gathering detailed information about the preferences, personalities, and information-consumption habits of the target audience, researchers can craft messages that resonate effectively.

As a simple example, academic findings might be highly detailed for scholarly journals and simplified for the general public. Further refinements can be made based on the cultural, educational, and professional background of the target audience.

2. Create the content

Creating compelling content is at the heart of effective research dissemination. Researchers must distill complex findings into a format that's engaging and easy to understand. In addition to the format of the presentation and the language used, content includes the visual or interactive elements that will make up the supporting materials.

Depending on the target audience, this may include complex technical jargon and charts or a more narrative approach with approachable infographics. For non-specialist audiences, the challenge is to provide the required information in a way that's engaging for the layperson.

3. Take a strategic approach to dissemination

There's no single best solution for all research dissemination needs. What’s more, technology and how target audiences interact with it is constantly changing. Developing a strategic approach to sharing research findings requires exploring the various methods and channels that align with the audience's preferences.

Each channel has a unique reach and impact, and a particular set of best practices to get the most out of it. Researchers looking to have the biggest impact should carefully weigh up the strengths and weaknesses of the channels they've decided upon and craft a strategy that best uses that knowledge.

4. Manage the timeline and resources

Time constraints are an inevitable part of research dissemination. Deadlines for publications can be months apart, conferences may only happen once a year, etc. Any avenue used to disseminate the research must be carefully planned around to avoid missed opportunities.

In addition to properly planning and allocating time, there are other resources to consider. The appropriate number of people must be assigned to work on the project, and they must be given adequate financial and technological resources. To best manage these resources, regular reviews and adjustments should be made.

- Tailoring communication of research findings

We’ve already mentioned the importance of tailoring a message to a specific audience. Here are some examples of how to reach some of the most common target audiences of research dissemination.

Making formal presentations

Content should always be professional, well-structured, and supported by data and visuals when making formal presentations. The depth of information provided should match the expertise of the audience, explaining key findings and implications in a way they'll understand. To be persuasive, a clear narrative and confident delivery are required.

Communication with stakeholders

Stakeholders often don't have the same level of expertise that more direct peers do. The content should strike a balance between providing technical accuracy and being accessible enough for everyone. Time should be taken to understand the interests and concerns of the stakeholders and align the message accordingly.

Engaging with the public

Members of the public will have the lowest level of expertise. Not everyone in the public will have a technical enough background to understand the finer points of your message. Try to minimize confusion by using relatable examples and avoiding any jargon. Visual aids are important, as they can help the audience to better understand a topic.

- 10 commandments for impactful research dissemination

In addition to the details above, there are a few tips that researchers can keep in mind to boost the effectiveness of dissemination:

Master the three Ps to ensure clarity, focus, and coherence in your presentation.

Establish and maintain a public profile for all the researchers involved.

When possible, encourage active participation and feedback from the audience.

Use real-time platforms to enable communication and feedback from viewers.

Leverage open-access platforms to reach as many people as possible.

Make use of visual aids and infographics to share information effectively.

Take into account the cultural diversity of your audience.

Rather than considering only one dissemination medium, consider the best tool for a particular job, given the audience and research to be delivered.

Continually assess and refine your dissemination strategies as you gain more experience.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 24 October 2024

Last updated: 30 January 2024

Last updated: 11 January 2024

Last updated: 17 January 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 12 October 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 31 January 2024

Last updated: 23 January 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, a whole new way to understand your customer is here, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules for innovative dissemination of research

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Open and Reproducible Research Group, Institute of Interactive Systems and Data Science, Graz University of Technology and Know-Center GmbH, Graz, Austria

Affiliation Center for Research and Interdisciplinarity, University of Paris, Paris, France

Affiliation Freelance Researcher, Vilnius, Lithuania

Affiliation University and National Library, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary

Affiliation Institute for Research on Population and Social Policies, National Research Council, Rome, Italy

Affiliation Open Knowledge Maps, Vienna, Austria

Affiliation National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Affiliation Center for Digital Safety and Security, AIT Austrian Institute of Technology, Vienna, Austria

- Tony Ross-Hellauer,

- Jonathan P. Tennant,

- Viltė Banelytė,

- Edit Gorogh,

- Daniela Luzi,

- Peter Kraker,

- Lucio Pisacane,

- Roberta Ruggieri,

- Electra Sifacaki,

- Michela Vignoli

Published: April 16, 2020

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007704

- Reader Comments

Author summary

How we communicate research is changing because of new (especially digital) possibilities. This article sets out 10 easy steps researchers can take to disseminate their work in novel and engaging ways, and hence increase the impact of their research on science and society.

Citation: Ross-Hellauer T, Tennant JP, Banelytė V, Gorogh E, Luzi D, Kraker P, et al. (2020) Ten simple rules for innovative dissemination of research. PLoS Comput Biol 16(4): e1007704. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007704

Editor: Russell Schwartz, Carnegie Mellon University, UNITED STATES

Copyright: © 2020 Ross-Hellauer et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This work was partly funded by the OpenUP project, which received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 710722. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: We have read the journal's policy and have the following conflicts: TR-H is Editor-in-Chief of the open access journal Publications . JT is the founder of the Open Science MOOC, and a former employee of ScienceOpen.

Introduction

As with virtually all areas of life, research dissemination has been disrupted by the internet and digitally networked technologies. The last two decades have seen the majority of scholarly journals move online, and scholarly books are increasingly found online as well as in print. However, these traditional communication vehicles have largely retained similar functions and formats during this transition. But digital dissemination can happen in a variety of ways beyond the traditional modes: social media have become more widely used among researchers [ 1 , 2 , 3 ], and the use of blogs and wikis as a specific form of ‘open notebook science’ has been popular for more than a decade [ 4 ].

Professional academic social networks such as ResearchGate and Academia.edu boast millions of users. New online formats for interaction with the wider public, such as TED talks broadcast via YouTube, often receive millions of views. Some researchers have even decided to make all of their research findings public in real time by keeping open notebooks [ 5 , 6 ]. In particular, digital technologies invoke new ways of reaching and involving audiences beyond their usual primary dissemination targets (i.e., other scholars) to actively involve peers or citizens who would otherwise remain out of reach for traditional methods of communication [ 7 ]. Adoption of these outlets and methods can also lead to new cross-disciplinary collaborations, helping to create new research, publication, and funding opportunities [ 8 ].

Beyond the increase in the use of web-based and computational technologies, other trends in research cultures have had a profound effect on dissemination. The push towards greater public understanding of science and research since the 1980s, and an emphasis on engagement and participation of non-research audiences have brought about new forms of dissemination [ 9 ]. These approaches include popular science magazines and science shows on television and the radio. In recent years, new types of events have emerged that aim at involving the general public within the research process itself, including science slams and open lab days. With science cafés and hackerspaces, novel, participatory spaces for research production and dissemination are emerging—both online and offline. Powerful trends towards responsible research and innovation, the increasing globalisation of research, and the emergence and inclusion of new or previously excluded stakeholders or communities are also reshaping the purposes of dissemination as well as the scope and nature of its audiences.

Many now view wider dissemination and public engagement with science to be a fundamental element of open science [ 10 ]. However, there is a paradox at play here, for while there have never been more avenues for the widespread dissemination of research, researchers tend nonetheless to value and focus upon just a few traditional outputs: journal articles, books, and conference presentations [ 11 ].

Following Wilson and colleagues [ 12 ], we here define research dissemination as a planned process that involves consideration of target audiences, consideration of the settings in which research findings are to be received, and communicating and interacting with wider audiences in ways that will facilitate research uptake and understanding. Innovative dissemination, then, means dissemination that goes beyond traditional academic publishing (e.g., academic journals, books, or monographs) and meetings (conferences and workshops) to achieve more widespread research uptake and understanding. Hence, a citizen science project, which involves citizens in data collection but does not otherwise educate them about the research, is not here considered innovative dissemination.

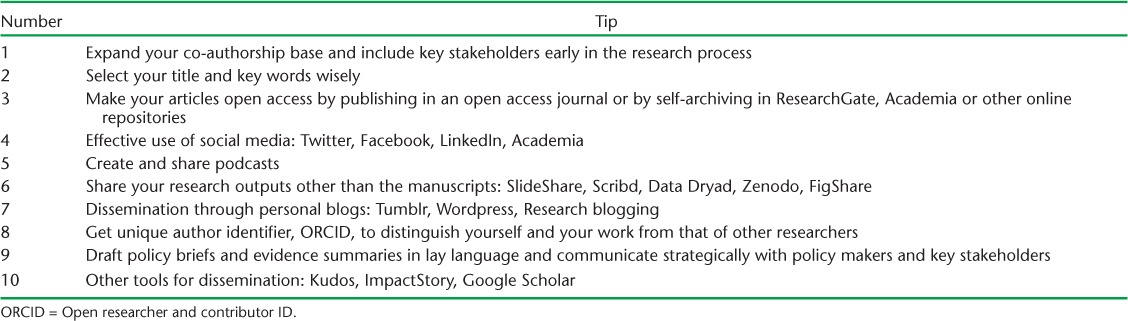

We here present 10 steps researchers can take to embrace innovative dissemination practices in their research, either as individuals or groups ( Fig 1 ). They represent the synthesis of multidimensional research activities undertaken within the OpenUP project ( https://www.openuphub.eu/ ). This European Coordination and Support Action grant award addressed key aspects and challenges of the currently transforming science landscape and proposed recommendations and solutions addressing the needs of researchers, innovators, the public, and funding bodies. The goal is to provide stakeholders (primarily researchers but also intermediaries) with an entry point to innovative dissemination, so that they can choose methods and tools based on their audience, their skills, and their requirements. The advice is directed towards both individual researchers and research teams or projects. It is similar to other entries in the Ten Simple Rules series (e.g., [ 13 , 14 ]). Ultimately, the benefit here for researchers is increased recognition and social impact of their work.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007704.g001

Rule 1: Get the basics right

Despite changes in communication technologies and models, there are some basic organisational aspects of dissemination that remain important: to define objectives, map potential target audience(s), target messages, define mode of communication/engagement, and create a dissemination plan. These might seem a bit obvious or laborious but are critical first steps towards strategically planning a project.

Define objectives

The motivation to disseminate research can come in many forms. You might want to share your findings with wider nonacademic audiences to raise awareness of particular issues or invite audience engagement, participation, and feedback. Start by asking yourself what you want to achieve with your dissemination. This first strategic step will make all other subsequent steps much simpler, as well as guide how you define the success of your activities.

Map your audience

Specify who exactly you want your research results to reach, for which purposes, and what their general characteristics might be (e.g., policy makers, patient groups, non-governmental organisations). Individuals are not just ‘empty vessels’ to be filled with new knowledge, and having a deeper contextual understanding of your audience can make a real difference to the success of your engagement practices. Who is most affected by your research? Who might find it most valuable? What is it that you want them to take away? Get to know your target audiences, their needs and expectations of the research outcomes, as well as their preferred communication channels to develop a detailed understanding of their interests and align your messages and media with their needs and priorities. Keep in mind, too, that intermediaries such as journalists or science communication organisations can support or mediate the dissemination process.

Target/frame your messages

Target and frame the key messages that you want to communicate to specific groups. Think first from the perspective of what they might want or need to hear from you, rather than what you want to tell them. Choosing media and format of your communication strongly depends on your communication objectives, i.e., what you want to achieve. There are many ways to communicate your research; for example, direct messages, blog/vlog posts, tweeting about it, or putting your research on Instagram. Form and content go hand in hand. Engage intermediaries and leverage any relevant existing networks to help amplify messages.

Create a dissemination plan

Many funded research projects require a dissemination plan. However, even if not, the formal exercise of creating a plan at the outset that organises dissemination around distinct milestones in the research life cycle will help you to assign roles, structure activities, as well as plan funds to be allocated in your dissemination. This will ultimately save you time and make future work easier. If working in groups, distribute tasks and effort to ensure regular updates of content targeted to different communities. Engage those with special specific skills in the use and/or development of appropriate communication tools, to help you in using the right language and support you in finding the suitable occasions to reach your identified audience. Research is not linear, however, and so you might find it best to treat the plan as a living document to be flexibly adapted as the direction of research changes.

Rule 2: Keep the right profile

Whether communicating as an individual researcher, a research project, or a research organisation, establishing a prominent and unique identity online and offline is essential for communicating. Use personal websites, social media accounts, researcher identifiers, and academic social networks to help make you and your research visible. When doing this, try to avoid any explicit self-promotion—your personal profile naturally will develop based on your ability to be an effective and impactful communicator.

Academia is a prestige economy, where individual researchers are often evaluated based on their perceived esteem or standing within their communities [ 15 ]. Remaining visible is an essential part of accumulating esteem. An online presence maintained via personal websites, social media accounts (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn), researcher identifiers (e.g., ORCID), and academic social networks (e.g., ResearchGate, institutional researcher profiles) can be a personal calling card, where you can highlight experience and demonstrate your expertise in certain topics. Being active on important mailing lists, forums, and social media is not only a good chance to disseminate your findings to those communities but also offers you the chance to engage with your community and potentially spark new ideas and collaborations.

Using researcher identifiers like ORCID when disseminating outputs will ensure that those outputs will be unambiguously linked back to the individual researcher (and even automatically updated to their ORCID profile). The OpenUP survey showed that nearly half of the respondents (41%) use academic social networks as a medium to disseminate their research, and a quarter of respondents (26%) said that these networks informed their professional work [ 16 ].

Create a brand by giving your project a unique name, ideally with some intuitive relation to the issue you are investigating. Create a striking visual identity, with a compelling logo, core colours, and a project slogan. Create a website that leverages this visual identity and is as simple and intuitive as possible, both in its layout and in the way content is formulated (limit insider jargon). Create associated appropriate social media accounts (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, SlideShare, YouTube) and link to this from the project website. Aim for a sustained presence with new and engaging content to reinforce project messaging, and this can help to establish a core following group or user base within different platforms. Include links to other project online presences such as social media accounts, or a rolling feed of updates if possible. Consider including a blog to disseminate core findings or give important project updates. A periodical newsletter could be released in order to provide project updates and other news, to keep the community informed and activated regarding project issues. Depending on the size of your project and budget, you might want to produce hard copy material such as leaflets or fact sheets, as well as branded giveaways to increase awareness of your project. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, try not to come across as a ‘scientific robot’, and make sure to communicate the more human personality side of research.

Rule 3: Encourage participation

In the age of open research, don’t just broadcast. Invite and engage others to foster participation and collaboration with research audiences. Scholarship is a collective endeavour, and so we should not expect its dissemination to be unidirectional, especially not in the digital age. Dissemination is increasingly done at earlier stages of the research life cycle, and such wider and more interactive engagement is becoming an integral part of the whole research workflow.

Such participative activities can be as creative as you wish; for example, through games, such as Foldit for protein folding ( https://fold.it/portal/ ). You might even find it useful to actively engage ‘citizen scientists’ in research projects; for example, to collect data or analyse findings. Initiatives such as Zooniverse ( https://www.zooniverse.org/ ) serve as great examples of allowing anyone to freely participate in cutting-edge ‘people-powered research’.

Disseminating early and often showcases the progress of your work and demonstrates productivity and engagement as part of an agile development workflow. People like to see progress and react positively to narrative, so give regular updates to followers on social media, for example, blogging or tweeting early research findings for early feedback. Alternatively, involving businesses early on can align research to industry requirements and expectations, thus potentially increasing commercial impact. In any case, active involvement of citizens and other target audiences beyond academia can help increase the societal impact of your research [ 17 ].

Rule 4: Open science for impact

Open science is ‘transparent and accessible knowledge that is shared and developed through collaborative networks’, as defined by one systematic review [ 18 ]. It encompasses a variety of practices covering a range of research processes and outputs, including areas like open access (OA) to publications, open research data, open source software/tools, open workflows, citizen science, open educational resources, and alternative methods for research evaluation including open peer review [ 19 ]. Open science is rooted in principles of equitable participation and transparency, enabling others to collaborate in, contribute to, scrutinise and reuse research, and spread knowledge as widely as possible [ 20 ]. As such, innovative dissemination is a core element of open science.

Embracing open science principles can boost the impact of research. Firstly, OA publications seem to accrue more citations than their closed counterparts, as well as having a variety of possible wider economic and societal benefits [ 21 ]. There are a number of ways to make research papers OA, including at the journal site itself, or self-archiving an accepted manuscript in a repository or personal website.

Disseminating publications as preprints in advance of or parallel to journal submission can increase impact, as measured by relative citation counts [ 22 ]. Very often, traditional publishing takes a long time, with the waiting time between submission and acceptance of a paper being in excess of 100 days [ 23 ]. Preprinting speeds up dissemination, meaning that findings are available sooner for sharing and reuse. Potential platforms for disseminating preprints include the Open Science Framework, biorXiv, or arXiv.

Dissemination of other open science outputs that would usually remain hidden also not only helps to ensure the transparency and increased reproducibility of research [ 24 ], but also means that more research elements are released that can potentially impact upon others by creating network effects through reuse. Making FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) research data and code available enables reuse and remixing of core research outputs, which can also lead to further citations for projects [ 25 , 26 , 27 ]. Published research proposals, protocols, and open notebooks act as advertisements for ongoing research and enable others to reuse methods, exposing the continuous and collaborative nature of scholarship.

To enable reuse, embrace open licenses. When it comes to innovative dissemination, the goal is usually that the materials are accessible to as large an audience as possible. If appropriate open licenses are not used, while materials may be free to access, they cannot be widely used, modified, or shared. The best in this case is the widely adopted Creative Commons licenses, CC BY or CC 0. Variations of these licenses are less permissive and can constrain reuse for commercial or derivative purposes. This limitation, however, prevents the use of materials in many forms of (open) educational resources and other open projects, including Wikipedia. Careful consideration should be given to licensing of materials, depending on what your intended outcomes from the project are (see Rule 1). Research institutes and funding bodies typically have a variety of policies and guidance about the use and licensing of such materials, and should be consulted prior to releasing any materials.

Rule 5: Remix traditional outputs

Traditional research outputs like research articles and books can be complemented with innovative dissemination to boost impact; for example, by preparing accompanying nonspecialist summaries, press releases, blog posts, and visual/video abstracts to better reach your target audiences. Free media coverage can be an easy way to get results out to as many people as possible. There are countless media outlets interested in science-related stories. Most universities and large research organisations have an office for public affairs or communication: liaise with these experts to disseminate research findings widely through public media. Consider writing a press release for manuscripts that have been accepted for publication in journals or books and use sample forms and tools available online to assist you in the process. Some journals also have dedicated press teams that might be able to help you with this.

Another useful tool to disseminate traditional research outputs is to release a research summary document. This one- or two-page document clearly and concisely summarises the key conclusions from a research initiative. It can combine several studies by the same investigator or by a research group and should integrate two main components: key findings and fact sheets (preferably with graphical images to illustrate your point). This can be published on your institutional website as well as on research blogs, thematic hubs, or simply posted on your social media profiles. Other platforms such as ScienceOpen and Kudos allow authors to attach nonspecialist summaries to each of their research papers.

To maximise the impact of your conference presentations or posters, there are several steps that can be taken. For instance, you can upload your slides to a general-purpose repository such as Figshare or Zenodo and add a digital object identifier (DOI) to your presentation. This also makes it easier to integrate such outputs with other services like ORCID. You can also schedule tweets before and during any conferences, and use the conference hashtag to publicise your talk or poster. Finally, you can also add information about your contributions to email signatures or out-of-office messages [ 28 ].

Rule 6: Go live

In-person dissemination does not just have to be at stuffy conferences. With research moving beyond the walls of universities, there are several types of places for more participatory events. Next to classic scientific conferences, different types of events addressing wider audiences have emerged. It is possible to hit the road and take part in science festivals, science slams, TEDx talks, or road shows.

Science slams are short talks in which researchers explain a scientific topic to a typically nonexpert audience. Similar to other short talk formats like TED talks, they lend themselves to being spread over YouTube and other video channels. A prominent example from the German-speaking area is Giulia Enders, who won the first prize in a science slam that took place in 2012 in Berlin. The YouTube video of her fascinating talk about the gut has received over 1 million views. After this success, she got an offer to write a book about the gut and the digestive system, which has since been published and translated into many languages. You never know how these small steps might end up having a wider impact on your research and career.

Another example is Science Shops, small entities which provide independent, participatory research support to civil society. While they are usually linked to universities, hacker and maker spaces tend to be community-run locations, where people with an interest in science, engineering, and art meet and collaborate on projects. Science festivals are community-based showcases of science and technology that take place over large areas for several days or weeks and directly involve researchers and practitioners in public outreach. Less formally, Science Cafés or similar events like Pint of Science are public engagement events in casual settings like pubs and coffeehouses.

Alternatively, for a more personal approach, consider reaching out to key stakeholders who might be affected by your research and requesting a meeting, or participating in relevant calls for policy consultations. Such an approach can be especially powerful in getting the message across to decision-makers and thought-leaders, although the resources required to schedule and potentially travel to such meetings means you should target such activities very carefully. And don’t forget the value of serendipity—who knows who you’ll meet in the course of your everyday meetings and travels. Always be prepared with a 30 second ‘elevator pitch’ that sums up your project in a confident and concise manner—such encounters may be the gateways to greater engagement or opportunities.

Rule 7: Think visual

Dissemination of research is still largely ruled by the written or spoken word. However, there are many ways to introduce visual elements that can act as attractive means to help your audience understand and interpret your research. Disseminate findings through art or multimedia interpretations. Let your artistic side loose or use new visualisation techniques to produce intuitive, attractive data displays. Of course, not everyone is a trained artist, and this will be dependent on your personal skills.

Most obviously, this could take the form of data visualisation. Graphic representation of quantitative information reaches back to ‘earliest map-making and visual depiction’ [ 29 ]. As technologies have advanced, so have our means of visually representing data.

If your data visualisations could be considered too technical and not easily understandable by a nonexpert reader, consider creating an ad hoc image for this document; sometimes this can also take the form of a graphical abstract or infographic. Use online tools to upload a sample of your data and develop smart graphs and infographics (e.g., Infogr.am, Datawrapper, Easel.ly, or Venngage).

Science comics can be used, in the words of McDermott, Partridge, and Bromberg [ 30 ], to ‘communicate difficult ideas efficiently, illuminate obscure concepts, and create a metaphor that can be much more memorable than a straightforward description of the concept itself’. McDermott and colleagues continue that comics can be used to punctuate or introduce papers or presentations and to capture and share the content of conference talks, and that some journals even have a ‘cartoon’ publication category. They advise that such content has a high chance of being ‘virally’ spread via social media.

As previously discussed, you may also consider creating a video abstract for a paper or project. However, as with all possible methods, it is worth considering the relative costs versus benefits of such an approach. Creating a high-quality video might have more impact than, say, a blog post but could be more costly to produce.

Projects have even successfully disseminated scientific findings through art. For example, The Civilians—a New York–based investigative theatre company—received a three-year grant to develop The Great Immensity , a play addressing the complexity of climate change. AstroDance tells the story of the search for gravitational waves through a combination of dance, multimedia, sound, and computer simulations. The annual Dance Your PhD contest, which began in 2007 and is sponsored by Science magazine, even asks scientists to interpret their PhD research as dance. This initiative receives approximately 50 submissions a year, demonstrating the popularity of novel forms of research dissemination.

Rule 8: Respect diversity

The academic discourse on diversity has always included discussions on gender, ethnic and cultural backgrounds, digital literacy, and epistemic, ideological, or economic diversity. An approach that is often taken is to include as many diverse groups into research teams as possible; for example, more women, underrepresented minorities, or persons from developing countries. In terms of scientific communication, however, not only raising awareness about diversity issues but also increasing visibility of underrepresented minorities in research or including more women in science communication teams should be considered, and embedded in projects from the outset. Another important aspect is assessing how the communication messages are framed, and if the chosen format and content is appropriate to address and respect all audiences. Research should reach all who might be affected by it. Respect inclusion in scientific dissemination by creating messages that reflect and respect diversity regarding factors like gender, demography, and ability. Overcoming geographic barriers is also important, as well as the consideration of differences in time zones and the other commitments that participants might have. As part of this, it is a key responsibility to create a healthy and welcoming environment for participation. Having things such as a code of conduct, diversity statement, and contributing guidelines can really help provide this for projects.

The 2017 Progression Framework benchmarking report of the Scientific Council made several recommendations on how to make progress on diversity and inclusion in science: (1) A strategy and action plan for diversity should developed that requires action from all members included and (2) diversity should be included in a wide range of scientific activities, such as building diversity into prizes, awards, or creating guidance on building diversity and inclusion across a range of demographics groups into communications, and building diversity and inclusion into education and training.

Rule 9: Find the right tools

Innovative dissemination practices often require different resources and skills than traditional dissemination methods. As a result of different skills and tools needed, there may be higher costs associated with some aspects of innovative dissemination. You can find tools via a more-complete range of sources, including the OpenUP Hub. The Hub lists a catalogue of innovative dissemination services, organised according to the following categories, with some suggested tools:

- Visualising data: tools to help create innovative visual representations of data (e.g., Nodegoat, DataHero, Plot.ly)

- Sharing notebooks, protocols, and workflows: ways to share outputs that document and share research processes, including notebooks, protocols, and workflows (e.g., HiveBench, Protocols.io, Open Notebook Science Network)

- Crowdsourcing and collaboration: platforms that help researchers and those outside academia to come together to perform research and share ideas (e.g., Thinklab, Linknovate, Just One Giant Lab)

- Profiles and networking: platforms to raise academic profile and find collaboration and funding opportunities with new partners (e.g., Humanities Commons, ORCID, ImpactStory)

- Organiding events: tools to help plan, facilitate, and publicise academic events (e.g., Open Conference Systems, Sched, ConfTool)

- Outreach to wider public: channels to help broadcast your research to audiences beyond academia, including policy makers, young people, industry, and broader society (e.g., Famelab, Kudos, Pint of Science)

- Publishing: platforms, tools, and services to help you publish your research (e.g., Open Science Framework, dokieli, ScienceMatters)

- Archive and share: preprint servers and repositories to help you archive and share your texts, data, software, posters, and more (e.g., BitBucket, GitHub, RunMyCode)

The Hub here represents just one attempt to create a registry of resources related to scholarly communication. A similar project is the 101 Innovations in Scholarly Communication project, which contains different tools and services for all parts of a generalised research workflow, including dissemination and outreach. This can be broadly broken down into services for communication through social media (e.g., Twitter), as well as those designed for sharing of scholarly outputs, including posters and presentations (e.g., Zenodo or Figshare). The Open Science MOOC has also curated a list of resources for its module on Public Engagement with Science, and includes key research articles, organisations, and services to help with wider scientific engagement.

Rule 10: Evaluate, evaluate, evaluate

Assess your dissemination activities. Are they having the right impact? If not, why not? Evaluation of dissemination efforts is an essential part of the process. In order to know what worked and which strategies did not generate the desired outcomes, all the research activities should be rigorously assessed. Such evaluation should be measured via the use of a combination of quantitative and qualitative indicators (which should be already foreseen in the planning stage of dissemination; see Rule 1). Questionnaires, interviews, observations, and assessments could also be used to measure the impact. Assessing and identifying the most successful practices will give you the evidence for the most effective strategies to reach your audience. In addition, the evaluation can help you plan your further budget and minimise the spending and dedicating efforts on ineffective dissemination methods.

Some examples of quantitative indicators include the following:

- Citations of publications;

- alternative metrics related to websites and social media platforms (updates, visits, interactions, likes, and reposts);

- numbers of events held for specific audiences;

- numbers of participants in those events;

- production and circulation of printed materials;

- media coverage (articles in specialised press newsletters, press releases, interviews, etc.); and

- how much time and effort were spent on activities.

Some examples of qualitative indicators include the following:

- Visibility in the social media and attractiveness of website;

- newly established contacts with networks and partners and the outcomes of these contacts;

- feedback from the target groups; and

- share feedback within your group on what dissemination strategies seemed to be the most effective in conveying your messages and reaching your target audiences.

We recognise that researchers are usually already very busy, and we do not seek to pressurise them further by increasing their burdens. Our recommendations, however, come at a time when there are shifting norms in how researchers are expected to engage with society through new technologies. Researchers are now often partially evaluated based on such, or expected to include dissemination plans in grant applications. We also do not want to encourage the further fragmentation of scholarship across different platforms and ‘silos’, and therefore we strongly encourage researchers to be highly strategic in how they engage with different methods of innovative dissemination. We hope that these simple rules provide guidance for researchers and their future projects, especially as the tools and services available evolve through time. Some of these suggestions or platforms might not work across all project types, and it is important for researchers to find which methods work best for them.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to everyone who engaged with the workshops we conducted as part of this grant award.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 19. Pontika N, Knoth P, Cancellieri M, Pearce S. Fostering Open Science to Research Using a Taxonomy and an ELearning Portal. In: iKnow: 15th International Conference on Knowledge Technologies and Data Driven Business, 21–22 Oct 2015, Graz, Austria [cited 2020 Mar 23]. Available from: http://oro.open.ac.uk/44719/

- 29. Friendly M. A Brief History of Data Visualization. In: Handbook of Data Visualization . Chen C, Härdle W, Unwin A, editors. Springer Handbooks Comp.Statistics. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-33037-0_2 . 2008. Pp.15–56.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 28, Issue 3

- Responsible dissemination of health and medical research: some guidance points

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7765-2443 Raffaella Ravinetto 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6275-6853 Jerome Amir Singh 2 , 3

- 1 Public Health Department , Institute of Tropical Medicine , Antwerpen , Belgium

- 2 Howard College School of Law , University of Kwazulu-Natal , Durban , South Africa

- 3 Dalla Lana School of Public Health , University of Toronto , Toronto , Ontario , Canada

- Correspondence to Dr Raffaella Ravinetto, Public Health Department, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerpen, Belgium; rravinetto{at}itg.be

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2022-111967

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- Global Health

Ravinetto and Singh argue that better practices can be implemented when disseminating research findings through abstracts, preprints, peer-reviewed publications, press releases and social media

Dissemination has been defined as ‘the targeted distribution of information and intervention materials to a specific public health or clinical practice audience’, 1 and as being ‘simply about getting the findings of your research to the people who can make use of them, to maximise the benefit of the research without delay’. 2 Ethics guidelines concur that research stakeholders have ethical obligations to disseminate positive, inconclusive or negative results, 3 in an accurate, comprehensive and transparent way 4 —even more so during public health emergencies. 5

Summary of research dissemination

What —Dissemination of health and medical research entails communicating the findings of research to stakeholders in ways that can facilitate understanding and use.

Why —Any positive, inconclusive or negative research findings should be disseminated to maximise the social value of the research and to accurately inform medical policies and practices.

When —Dissemination of health and medical research should occur as soon as possible after completion of interim and final analysis, particularly during public health emergencies.

Who —Researchers, research institutions, sponsors, developers, publishers and editors must ensure the timely and accurate dissemination of research findings. Similarly, the scientific community should critically appraise research findings; policymakers and clinicians should weigh the implications of research findings for policy and clinical practice; while mainstream media should communicate the implications of research findings to the general public in a manner that facilitates understanding.

How —Research findings are primarily disseminated via press releases, preprints, abstracts and peer-reviewed publications. To ensure timely, comprehensive, accurate, unbiased, unambiguous and transparent dissemination, all research stakeholders should integrate ethics and integrity principles in their institutional dissemination policies and personal belief systems.

Peer-reviewed publications

Publication in peer-reviewed journals remains the benchmark dissemination modality. Independent peer-review aims to assure the quality, accuracy and credibility of reports, but does not always prevent the publication of poorly written, dubious or even fraudulent manuscripts, 9 particularly if there is dearth of qualified reviewers, and/or an findings are hastily published to gain competitive advantage and visibility. 10 Furthermore, researchers who are inexperienced or subject to an institutional ethos of ‘publish or perish’, may choose to publish in predatory journals with highly questionable marketing and peer-review practices. 11 While target audiences may be unable to access findings if journal content is not freely accessible on the Internet, some researchers, particularly those in resource-constrained settings 12 may be unable to publish their research due to resource constraints (eg, publication fees may be prohibitively high). 13 Some may be poorly motivated to publish inconclusive or negative data. 14 Because of such shortcomings, commentators such as Horby warn that ‘clinicians should not rely solely on peer review to assess the validity and meaningfulness of research findings’. 15

For peer-reviewed publications to remain a key-dissemination modality, editors should follow the Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals , of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, and comply with the core practices of the Committee on Publication Ethics (eg, data and reproducibility, ethical oversight, authorship and contributorship, etc.). This entails going beyond a ‘checklist approach’ and subjecting manuscripts to rigorous screening and assessment. Journals should strive to select qualified independent reviewers and prioritise open-access policies. Research institutions should distance themselves from a ‘publish or perish’ culture which, together with the willingness to hide ‘unfavourable’ results, remains a major driver of unethical publication practices—which, in turn, translates to ill-informed policies and practices. 16

Scientific conferences are valuable venues for sharing research results with peers, and getting prepublication critical feedback. Abstracts often appear in the supplement of a scientific journal, which reaches a broader audience. However, even if attendance costs are not prohibitively expensive, the selection of abstracts may be highly competitive. As a result, not all research findings—even of topical interest—are selected. Furthermore, even if selection is conducted by independent experts, the limited information contained in an abstract may mask scientific and/or ethical shortcomings in the work.

Communication via abstracts is laudable, but should be rapidly followed by peer-reviewed publications, which allows for the findings to be comprehensively reviewed by experts. When abstracts remain the sole source of information, the findings’ significance might be misunderstood, overestimated or wrongly used to guide behaviours, policies and practices.

Preprints, that is, preliminary reports of work not yet peer-reviewed, are uploaded in dedicated free-access servers, such as https://www.medrxiv.org/ . Preprints are increasingly being used by health researchers, thanks to the evolving policies of major journals that now accept manuscripts previously posted as preprints. 17 Theoretically, preprints possess high value as they allow for rapid, open-access dissemination, and immediate yet informal peer-appraisal in the comments section. However, preprints also hold implicit risks. For instance, rapidity may detract from quality and accuracy; most peers will not be able to systematically invest time for the expected high-quality feedback; rushed or inexperienced readers may miss the (sometimes, small print) cautioning that preprints should not be considered established information, nor become the basis for informing policy or medical guidelines; and findings from preprints that may later be substantially revised or rejected after undergoing peer-review processes, could continue to be relied on and disseminated if, for example, they were included in scoping or systematic reviews before peer-review (the same applies to retracted peer-reviewed manuscripts).

To mitigate such risks, researchers should submit preprint manuscripts to a peer-reviewed journal as soon as reasonably possible, and transparently communicate on negative peer-review outcomes, or justify why the preprint is not being timeously submitted to a peer-review journal. Once accepted or published, researchers could remove their preprint from preprint servers or link to the final published version. The media have a duty to communicate preprint findings as unreviewed and subject to change. The scientific community should reach agreement on ‘Good Preprint Practices’ and ascribe less ambiguous terminology to preprints (eg, ‘Not peer-reviewed’ or ‘Peer-review pending’). 18

Press releases, media coverage and social media

Since 2021, the dissemination of clinical trial findings by corporate press release has almost become synonymous with announcements of COVID-19 scientific breakthroughs. Therefore, it seems important to briefly contextualise the strategy underpinning such dissemination. Corporate press releases are often preceded by stock repurchasing or ‘buybacks’, that is, companies buy back part of their own stock held by executives. This increases demand for the stock and enhances earnings per share. 19 Pharmaceutical or biotechnology companies typically engage in strategically timed buybacks, before press releases announcing significant research findings. Furthermore, corporates in the USA and elsewhere may employ press releases to comply with the legal requirements to disclose information that impact on their market values, and changes in their ‘financial conditions and operations’. 20 Press releases are typically drafted by marketing experts and they are often first aimed at the market, and driven by corporate interests rather than social value.

For researchers, the potential to amplify scientific visibility through mass media may act as a powerful incentive to indulge in flattering but inaccurate language. Nonetheless, they have a moral responsibility to review press releases for accuracy, and to immediately make key-information including the protocol, analysis plan and detailed results, publicly available. For instance, the media briefing that announced on 16 June 2020 the life-saving benefit of dexamethasone in severe COVID-19 was followed on 26 June by a preprint with full trial results 15 . In ab sence of such good practices, press releases can contain inaccuracies or overhype findings 7 with major damaging downstream effects. 16

The media have an equally significant impact on science dissemination: peer-reviewed publications which receive more attention from lay-press, are more likely to be cited in scientific literature. 21 Perceived media credibility also impacts on dissemination: once individuals trust a media source, 22 they often let down their guard on evaluating the credibility of that source. This speaks to the importance of discerning media dissemination ( box 2 ). Journalists who cover early press releases should critically appraise them considering their limitations and potential conflicts of interest.

Recommendations for journalists

Recommendations for journalists who cover (early) press release.

A. Always be conscious of the power of the media to shape the views, fears and beliefs of the public, in the short term, medium term and long term.

B. Weigh the tone and the extent of coverage afforded to press releases, based, among other factors, on:

A critical appraisal of whether the press release was preceded by stock buyouts and/or aimed at influencing corporates share values.

A critical appraisal of the science underpinning the press release, such as the sample size, study population representativeness (for instance, age, sex, ethnicity), research questions that are not addressed yet, and any omissions of potential harms.

A recourse to the views of independent scientists, paying attention to any declared or undeclared conflicts of interest that may bias their opinions.

C. Critically appraise the accuracy and possible biases of (independent) scientists’ opinions on press releases, when shared on personal social media feeds, before deciding whether to afford coverage to such views.

D. Afford the same coverage given to the initial press release (or more, if necessary) to any significant follow-up information-related thereto.

A call for good dissemination practices

The scientific community, health system policy-makers and regulators are the primary audience of peer-reviewed manuscripts, abstracts and preprints. These constituents should be, or become, ‘sufficiently skilled in critical thinking and scientific methods that they can make sensible decisions, regardless of whether an article is peer reviewed or not’ 15 ; understand that the nature of scientific knowledge is incremental and cumulative (one study seldom changes practice on its own); and also critically assess other sources, for example, pharmacovigilance, etc. Conversely, corporate press releases are aimed at influencing the market, and society as a whole—and not suited for scientific appraisal.

Irrespective of dissemination modalities, upstream information is cascaded to mainstream and social media, spreading knowledge but risk catalysing misunderstanding or overemphasis. Risks are only partially mitigated by independent quality control on the upstream information (relatively stringent in peer-review, weaker in preprints and abstracts, and virtually absent for press releases). In table 1 , we summarise recommendations for good dissemination practices, aimed at researchers, research institutions, developers, medical journals editors, media, journalists, social media actors, medical opinion leaders, policy-makers, regulators and the scientific community. All these stakeholders should integrate ethics and integrity in their policies and behaviours, to ensure timely, comprehensive, accurate, unbiased, unambiguous and transparent dissemination of research findings.

- View inline

Summary of the recommendations for good dissemination practices

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

- The Unites States Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- National Institute for Health Care and Research

- World Medical Association

- Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS)

- ↵ WHO guidelines on ethical issues in public health surveillance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Accessed on 21/04/2022 at P214263_WHO Guidelines on Ethical Issues_COUV.indd .

- Massey DS ,

- Wallach JD , et al

- McMahon JH ,

- Lydeamore MJ ,

- Stewardson AJ

- Cashin AG ,

- Richards GC ,

- DeVito NJ , et al

- Upshur REG ,

- Zdravkovic M ,

- Berger-Estilita J ,

- Zdravkovic B , et al

- Ellingson MK ,

- Skydel JJ , et al

- Kmietowicz Z

- Ravinetto R

- Ravinetto R ,

- Caillet C ,

- Zaman MH , et al

- ↵ et al Sorkin AR , Karaian J , Gandel S . Biden Renews Pushback against stock Buybacks , 2022 . Available: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/28/business/dealbook/biden-stock-buybacks.html

- Neuhierl A ,

- Scherbina A ,

- Schlusche B

- Anderson PS ,

- Gray HM , et al

- Pew Research Centre

Twitter @RRavinetto

Contributors This manuscript was jointly written by RR and JAS.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

How to disseminate your research

- Published: 01 January 2019

- Version: V Version 1.0 - January 2019

This guide is for researchers who are applying for funding or have research in progress. It is designed to help you to plan your dissemination and give your research every chance of being utilised.

What does NIHR mean by dissemination?

Effective dissemination is simply about getting the findings of your research to the people who can make use of them, to maximise the benefit of the research without delay.

“Research is of no use unless it gets to the people who need to use it”

Professor Chris Whitty, Chief Scientific Adviser for the Department of Health

Principles of good dissemination

Stakeholder engagement: Work out who your primary audience is; engage with them early and keep in touch throughout the project, ideally involving them from the planning of the study to the dissemination of findings. This should create ‘pull’ for your research i.e. a waiting audience for your outputs. You may also have secondary audiences and others who emerge during the study, to consider and engage.

Format: Produce targeted outputs that are in an appropriate format for the user. Consider a range of tailored outputs for decision makers, patients, researchers, clinicians, and the public at national, regional, and/or local levels as appropriate. Use plain English which is accessible to all audiences.

Utilise opportunities: Build partnerships with established networks; use existing conferences and events to exchange knowledge and raise awareness of your work.

Context: Understand the service context of your research, and get influential opinion leaders on board to act as champions. Timing: Dissemination should not be limited to the end of a study. Consider whether any findings can be shared earlier

Remember to contact your funding programme for guidance on reporting outputs .

Your dissemination plan: things to consider

What do you want to achieve, for example, raise awareness and understanding, or change practice? How will you know if you are successful and made an impact? Be realistic and pragmatic.

Identify your audience(s) so that you know who you will need to influence to maximise the uptake of your research e.g. commissioners, patients, clinicians and charities. Think who might benefit from using your findings. Understand how and where your audience looks for/receives information. Gain an insight into what motivates your audience and the barriers they may face.

Remember to feedback study findings to participants, such as patients and clinicians; they may wish to also participate in the dissemination of the research and can provide a powerful voice.

When will dissemination activity occur? Identify and plan critical time points, consider external influences, and utilise existing opportunities, such as upcoming conferences. Build momentum throughout the entire project life-cycle; for example, consider timings for sharing findings.

Think about the expertise you have in your team and whether you need additional help with dissemination. Consider whether your dissemination plan would benefit from liaising with others, for example, NIHR Communications team, your institution’s press office, PPI members. What funds will you need to deliver your planned dissemination activity? Include this in your application (or talk to your funding programme).

Partners / Influencers: think about who you will engage with to amplify your message. Involve stakeholders in research planning from an early stage to ensure that the evidence produced is grounded, relevant, accessible and useful.

Messaging: consider the main message of your research findings. How can you frame this so it will resonate with your target audience? Use the right language and focus on the possible impact of your research on their practice or daily life.

Channels: use the most effective ways to communicate your message to your target audience(s) e.g. social media, websites, conferences, traditional media, journals. Identify and connect with influencers in your audience who can champion your findings.

Coverage and frequency: how many people are you trying to reach? How often do you want to communicate with them to achieve the required impact?

Potential risks and sensitivities: be aware of the relevant current cultural and political climate. Consider how your dissemination might be perceived by different groups.

Think about what the risks are to your dissemination plan e.g. intellectual property issues. Contact your funding programme for advice.

More advice on dissemination

We want to ensure that the research we fund has the maximum benefit for patients, the public and the NHS. Generating meaningful research impact requires engaging with the right people from the very beginning of planning your research idea.

More advice from the NIHR on knowledge mobilisation and dissemination .

- Request new password

- Create a new account

Doing Research in Counselling and Psychotherapy

Student resources, disseminating the findings of your research study.

It is very important to find appropriate ways to disseminate the findings of your research – projects that sit on office or library shelves and are seldom or never read represent a tragic loss to the profession.

A key dimension of research dissemination is to be actively involved with potential audiences for your work, and help them to understand what it means to them. These dialogues also represent invaluable learning experiences for researchers, in terms of developing new ideas and appreciating the methodological limitations of their work. An inspiring example of how to do this can be found in:

Granek, L., & Nakash, O. (2016). The impact of qualitative research on the “real world” knowledge translation as education, policy, clinical training, and clinical practice. Journal of Humanistic Psychology , 56(4), 414 – 435.

A further key dimension of research dissemination lies in the act of writing. There are a number of challenges associated with writing counselling and psychotherapy research papers, such as the need to adhere to journal formats, and the need (sometimes) to weave personal reflective writing into a predominantly third-person standard academic style. The items in the following sections explore these challenges from a variety of perspectives.

Suggestions for becoming a more effective academic writer

Sources of advice on how to ease the pain of writing:

Gioia, D. (2019). Gioia’s rules of the game. Journal of Management Inquiry , 28(1), 113 – 115.

Greenhalgh, T. (2019). Twitter women’s tips on academic writing: a female response to Gioia’s rules of the game. Journal of Management Inquiry , 28(4), 484 – 487.

Roulston, K. (2019). Learning how to write successfully from academic writers. The Qualitative Report, 24(7), 1778 – 1781.

Writing tips from the student centre, University of Berkeley

The transition from being a therapist to being a researcher

Finlay, L. (2020). How to write a journal article: Top tips for the novice writer. European Journal for Qualitative Research in Psychotherapy , 10, 28 – 40.

McBeath, A., Bager-Charleson, S., & Abarbanel, A. (2019). Therapists and academic writing: “Once upon a time psychotherapy practitioners and researchers were the same people”. European Journal for Qualitative Research in Psychotherapy , 9, 103 – 116.

McPherson, A. (2020). Dissertation to published article: A journey from shame to sharing. European Journal for Qualitative Research in Psychotherapy , 10, 41 – 52.

Journal article style requirements of the American Psychological Association (including a section on writing quantitative papers)

Writing qualitative reports

Jonsen, K., Fendt, J., & Point, S. (2018). Convincing qualitative research: What constitutes persuasive writing? Organizational Research Methods , 21(1), 30 – 67.

Ponterotto, J.G. & Grieger, I. (2007). Effectively communicating qualitative research. The Counseling Psychologist , 35, 404 – 430.

Smith, L., Rosenzweig, L. & Schmidt, M. (2010). Best practices in the reporting of participatory action research: embracing both the forest and the trees. The Counseling Psychologist, 38, 1115 – 1138.

Staller, K.M. & Krumer-Nevo, M. (2013). Successful qualitative articles: A tentative list of cautionary advice. Qualitative Social Work, 12, 247 – 253.

Clark, A.M. & Thompson, D.R. (2016). Five tips for writing qualitative research in high-impact journals: moving from #BMJnoQual . International Journal of Qualitative Methods , 15, 1 – 3

Gustafson, D. L., Parsons, J. E., & Gillingham, B. (2019). Writing to transgress: Knowledge production in feminist participatory action research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20 . DOI: 10.17169/fqs-20.2.3164

Caulley, D.N. (2008). Making qualitative reports less boring: the techniques of writing creative nonfiction. Qualitative Inquiry, 14, 424 – 449.

Disseminating research findings: what should researchers do? A systematic scoping review of conceptual frameworks

Affiliation.

- 1 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, YO10 5DD, UK. [email protected].

- PMID: 21092164

- PMCID: PMC2994786

- DOI: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-91

Background: Addressing deficiencies in the dissemination and transfer of research-based knowledge into routine clinical practice is high on the policy agenda both in the UK and internationally.However, there is lack of clarity between funding agencies as to what represents dissemination. Moreover, the expectations and guidance provided to researchers vary from one agency to another. Against this background, we performed a systematic scoping to identify and describe any conceptual/organising frameworks that could be used by researchers to guide their dissemination activity.

Methods: We searched twelve electronic databases (including MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO), the reference lists of included studies and of individual funding agency websites to identify potential studies for inclusion. To be included, papers had to present an explicit framework or plan either designed for use by researchers or that could be used to guide dissemination activity. Papers which mentioned dissemination (but did not provide any detail) in the context of a wider knowledge translation framework, were excluded. References were screened independently by at least two reviewers; disagreements were resolved by discussion. For each included paper, the source, the date of publication, a description of the main elements of the framework, and whether there was any implicit/explicit reference to theory were extracted. A narrative synthesis was undertaken.

Results: Thirty-three frameworks met our inclusion criteria, 20 of which were designed to be used by researchers to guide their dissemination activities. Twenty-eight included frameworks were underpinned at least in part by one or more of three different theoretical approaches, namely persuasive communication, diffusion of innovations theory, and social marketing.

Conclusions: There are currently a number of theoretically-informed frameworks available to researchers that can be used to help guide their dissemination planning and activity. Given the current emphasis on enhancing the uptake of knowledge about the effects of interventions into routine practice, funders could consider encouraging researchers to adopt a theoretically-informed approach to their research dissemination.

Grants and funding

- MC_U130085862/MRC_/Medical Research Council/United Kingdom

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Ten tips to improve the visibility and dissemination of research for policy makers and practitioners

J p tripathy, a bhatnagar, h d shewade, a m v kumar, r zachariah, a d harries.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

CORRESPONDENCE Jaya Prasad Tripathy, International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease South-East Asia Office, C-6 Qutub Institutional Area, New Delhi, 110 016 India, e-mail: [email protected] , [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Received 2016 Oct 7; Accepted 2017 Dec 2; Issue date 2017 Mar 21.

Effective dissemination of evidence is important in bridging the gap between research and policy. In this paper, we list 10 approaches for improving the visibility of research findings, which in turn will hopefully contribute towards changes in policy. Current approaches include using social media (Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn); sharing podcasts and other research outputs such as conference papers, posters, presentations, reports, protocols, preprint copy and research data (figshare, Zenodo, Slideshare, Scribd); and using personal blogs and unique author identifiers (ORCID, ResearcherID). Researchers and funders could consider drawing up a systematic plan for dissemination of research during the stage of protocol development.

Keywords: open access, Twitter, Facebook, social media, policy brief

Une dissémination efficace des résultats de recherche est cruciale pour combler le fossé qui existe entre la recherche et la politique de santé, ainsi que sa mise en œuvre. Dans cet article, nous énumérons 10 approches visant à améliorer la visibilité des résultats de la recherche qui vont, si tout va bien, à leur tour contribuer au changement en matière de politique. Les approches actuelles incluent le recours aux réseaux sociaux (Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn), le partage de podcasts et d'autres résultats de recherche comme des documents de conférences, des affiches, des présentations, des rapports, des protocoles, des photocopies, des données de recherche (figshare, Zenodo, Slideshare, Scribd), l'utilisation d'un blog personnel et un identifiant unique de l'auteur (ORCID, ResearcherID). Les chercheurs et les financeurs pourraient envisager d'ébaucher un plan systématique de dissémination de la recherche dès l'élaboration du protocole.

Es importante lograr una difusión eficaz de las pruebas científicas, con el objeto de superar la brecha que existe entre la investigación y las políticas y las prácticas. En el presente artículo se mencionan diez enfoques que mejoran la visibilidad de los resultados de las investigaciones, con la intención de que contribuyan a su vez a la modificación de las políticas. Las estrategias vigentes incluyen la utilización de las redes sociales (Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn), el intercambio de las redifusiones multimedia (podcasts) y de otros productos de las investigaciones como son los artículos, los afiches, las presentaciones en las conferencias, los informes, los protocolos, los manuscritos antes de su publicación, los datos de investigación (figshare, Zenodo, Slideshare, Scribd) y la utilización de bitácoras personales (blogs) y de los identificadores únicos de los investigadores (ORCID, ResearcherID). Los investigadores y las instituciones patrocinadoras deben procurar la elaboración de un plan sistemático de difusión de las investigaciones durante la etapa de preparación del protocolo.

The full potential for research evidence to influence changes in decision-making and policy and practice is not yet being realised. 1 Keeping in mind the growing interest in bridging the gap between research and policy and practice, effective dissemination in an appropriate format is of vital importance. If we wish to maximise the benefits of publication and its eventual influence on policy and practice, there are a number of actions that can be taken before and after the paper is published.