- Social Psychology

Dutton and Aron and the Misattribution of Arousal Theory

Shopping Cart

Articles & Insights

Expand your mind and be inspired with Achology's paradigm-shifting articles. All inspired by the world's greatest minds!

Cognitive Process & Emotional Perception: Insights from The Misattribution of Arousal Study

By declan fitzpatrick, this article is divided into the following sections:.

The Misattribution of Arousal, a concept explored by psychologists Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron in the 1970s, has significantly contributed to our understanding of emotional perception and cognitive processes. This influential research aimed to understand how individuals misinterpret physiological arousal, attributing it to the wrong source, thus affecting their emotional experiences.

By examining the methodology, findings, and implications of the Misattribution of Arousal studies, we can gain crucial insights into the complexities of human emotions, relationships, and decision-making.

Methodology and Design

Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron designed a series of experiments to investigate the concept of misattributed arousal. One of their most famous studies involved an experimental setup on two bridges in Vancouver, Canada: one a sturdy, low-lying bridge, and the other a wobbly suspension bridge high above a river. These bridges were chosen to induce different levels of physiological arousal due to varying degrees of perceived danger.

Male participants crossing each bridge were approached by an attractive female confederate who asked them to fill out a survey and offered her phone number for potential follow-up questions. The researchers hypothesized that the heightened physiological arousal from crossing the more frightening suspension bridge would be misattributed to the attractiveness of the female interviewer, leading to increased romantic attraction.

This experimental design allowed Dutton and Aron to isolate the effects of situationally induced arousal on emotional perception, providing empirical data on how physiological states influence cognitive interpretations and emotional responses.

Key Findings

The results of the Misattribution of Arousal studies were revealing and groundbreaking for understanding emotional perception. Dutton and Aron found that male participants who crossed the suspension bridge were significantly more likely to contact the female interviewer afterward compared to those who crossed the stable bridge. This finding suggested that the arousal induced by the fear of crossing the suspension bridge was misattributed to feelings of romantic attraction toward the female confederate.

These findings highlighted the powerful role of physiological arousal in shaping emotional experiences. The research demonstrated that individuals often incorrectly attribute their physical sensations to the wrong source, leading to altered emotional perceptions. This phenomenon showed how easily our cognitive processes could be influenced by external factors, resulting in misinterpretations of our own emotional states.

The Misattribution of Arousal studies provided compelling evidence that emotions are not solely based on internal cues but are significantly shaped by the context in which physiological arousal occurs. This research underscored the importance of understanding the interplay between physiological and cognitive factors in shaping our emotional experiences.

Psychological Mechanisms and Implications

The Misattribution of Arousal studies illuminated several psychological mechanisms underlying emotional perception. One key factor is the role of cognitive labeling, where individuals interpret physiological arousal based on contextual cues. When experiencing heightened arousal, people look for explanations in their environment, often attributing their physical state to the most salient or plausible cause.

Another important mechanism is the concept of arousal transfer, where physiological arousal from one source influences emotional responses to unrelated stimuli. This transfer occurs because the body’s physiological state remains elevated, leading individuals to misattribute their arousal to subsequent events or interactions. The studies by Dutton and Aron demonstrated how this process could lead to heightened romantic attraction when combined with fear-induced arousal.

These insights have profound implications for understanding the complexities of emotional perception and the factors that influence our emotional experiences. The findings emphasize the importance of context in shaping emotions and highlight the need for critical awareness of how external factors can impact our cognitive interpretations. In various contexts, from interpersonal relationships to marketing strategies to decision-making processes, recognizing and addressing the potential for misattribution of arousal can lead to more accurate and authentic emotional experiences.

Ethical Considerations

While the Misattribution of Arousal studies provided valuable insights into emotional perception, they also raised ethical considerations related to the manipulation of participants’ arousal states. The experiments involved inducing heightened physiological arousal through potentially anxiety-provoking situations, raising questions about the potential distress experienced by participants.

Modern ethical standards prioritize minimizing harm and ensuring the welfare of research participants. Researchers must obtain informed consent, provide thorough debriefing, and ensure that any induced behaviors do not have adverse long-term effects. The ethical controversies surrounding the Misattribution of Arousal studies have contributed to the development of stricter guidelines to protect participants while advancing scientific knowledge.

Broader Societal Impact

The insights gained from the Misattribution of Arousal studies have had significant implications for various domains, including relationships, therapy, and advertising. Understanding the impact of misattributed arousal on emotional experiences can inform strategies to promote healthy relationships, improve therapeutic interventions, and create effective marketing campaigns.

In the realm of relationships, recognizing the potential for misattribution of arousal can guide individuals and couples in understanding the true sources of their emotions. This awareness can help in navigating romantic relationships and distinguishing genuine emotional connections from those influenced by external factors.

In therapy, the findings of the Misattribution of Arousal studies underscore the importance of addressing the context in which emotional experiences occur. Therapists can use this knowledge to help clients identify and reframe misattributed emotions, leading to more accurate self-awareness and healthier emotional regulation.

In advertising and marketing, the insights from the Misattribution of Arousal studies highlight the potential for strategic use of arousal-inducing stimuli to influence consumer behavior. By understanding how emotional responses can be shaped by contextual factors, marketers can design campaigns that elicit desired emotional reactions and drive customer engagement.

Theoretical Contributions

The Misattribution of Arousal studies have made significant contributions to psychological theories, particularly in understanding the interplay between physiological arousal and cognitive interpretation in shaping emotional experiences. They provided empirical support for the concept of cognitive labeling and highlighted the role of arousal transfer in influencing emotional responses.

The research also contributed to the broader discourse on cognitive and social psychology, emphasizing the importance of context in shaping our emotional perceptions. By elucidating the mechanisms underlying misattributed arousal, the studies by Dutton and Aron have informed theoretical frameworks and research on emotion, cognition, and interpersonal relationships.

The Misattribution of Arousal studies conducted by Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron remain a cornerstone in the study of emotional perception and cognitive processes. The research highlights the importance of context in shaping emotions and emphasizes the need for critical awareness of how external factors influence our cognitive interpretations. It underscores the significance of thoughtful and ethical approaches to understanding and addressing the complexities of emotional perception.

Their contributions to our understanding of emotional perception provide valuable guidance for creating conditions that promote accurate and authentic emotional experiences. Ultimately, the Misattribution of Arousal studies serve as a powerful reminder of the intricate interplay between physiological and cognitive factors in shaping human emotions and behavior.

Browse Achology Quotes:

► Book Recommendation of the Month

The ultimate life coaching handbook by kain ramsay.

A Comprehensive Guide to the Methodology, Principles and practice of Life Coaching

Misconceptions and industry shortcomings make life coaching frequently misunderstood, as many so-called coaches fail to achieve real results. The lack of wise guidance further fuels this widespread skepticism and distrust.

Get updates from the Academy of Modern Applied Psychology

About Achology

Useful links, our policies, our 7 schools, connect with us, © 2024 achology.

There was a problem reporting this post.

Block Member?

Please confirm you want to block this member.

You will no longer be able to:

- Mention this member in posts

Please allow a few minutes for this process to complete.

Psychology Concepts

Dutton and aron suspension bridge experiment.

The suspension bridge experiment was conducted by Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron in 1974, in order to demonstrate a process where people apparently misjudge the cause of a high level of arousal. The results of the experiment showed that the men who were approached by an attractive woman on a less secure bridge were found to experience a higher level of arousal, and had a tendency to attribute this to the presence of the woman.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

Misattribution of Arousal

Misattribution of arousal definition.

Misattribution of Arousal Background

The concept of misattribution of arousal is based on Stanley Schachter’s two-factor theory of emotion. Although most people probably think they just spontaneously know how they feel, experiencing an emotion is a little more complicated according to the two-factor theory. The theory suggests that two components are necessary to experience an emotion: physiological arousal and a label for it. Schachter suggested that physiological states are ambiguous, so one looks to the situation to figure out how one feels. So if your heart is pounding and you have just swerved out of the way of an oncoming car, you will attribute the pounding heart to the accident you almost had, and therefore will label your emotion “fear.” But if your near collision is with a classmate upon whom you have recently developed a crush, you would probably interpret your pounding heart quite differently. You may think, “This must be love that I am feeling.” Based on the two-factor theory, emotional experience is malleable because the emotion experienced depends partly on one’s interpretation of the events that caused the physiological arousal.

Classic Research on Misattribution of Arousal

Schachter and his colleague Jerome Singer tested the misattribution of arousal hypothesis in a classic experiment conducted in 1962. They told participants that they were testing the effects of a vitamin on people’s vision. In reality, however, some participants were injected with epinephrine (a drug that causes arousal, such as increased heart rate and shakiness). Of these participants, some were warned that the drug causes arousal and others were not. Schachter and Singer predicted that participants who were not informed of the drug’s effects would look to the situation to try to figure out what they were feeling. Therefore, participants unknowingly given the arousal-causing drug were expected to display emotions more consistent with situational cues compared with participants not given the drug and participants accurately informed about the drug’s effects. The results of the experiment supported this hypothesis. Compared with participants in the other two conditions, participants who had received the drug with no information about its effects were more likely to report feeling angry when they were left waiting in a room with a confederate (a person who appeared to be another participant but was actually part of the experiment) who acted angry about the questionnaire that he and the real participant had been asked to complete. Likewise, when the confederate acted euphoric, participants in this condition were also more likely to feel happy. With no information about the actual source of their arousal, these participants looked to the context (their fellow participants) to acquire information about what they were actually feeling. In contrast, participants told about the drug’s effects had an accurate explanation for their arousal and therefore did not misattribute it, and participants not given the drug did not have any arousal to attribute at all. These findings parallel the example of the professor who did not know that caffeine was responsible for her jitters and therefore felt nervous instead of buzzed. In each case, attributing one’s arousal to an erroneous source altered one’s emotional experience.

In a classic experiment conducted by Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron in 1974, the misattribution of arousal effect was shown to even affect feelings of attraction. In this experiment, an attractive female experimenter approached men as they crossed either a high, rickety suspension bridge or a low, safe bridge at a popular tourist site in Vancouver, Canada. Whenever an unaccompanied male began to walk across either bridge, he was approached by a female researcher who asked him to complete a questionnaire. Upon completion, the researcher wrote her phone number on a corner of the page and said that he should feel free to call her if he wanted information about the study results. The researchers found that more men called the woman after crossing the rickety bridge compared with the stable bridge. The explanation for this finding is that men in this condition were presumably breathing a bit more rapidly and had their hearts beating a bit faster than usual as a result of crossing the scary bridge, and when these effects occurred in the presence of an attractive woman, they misattributed this arousal to feelings of attraction.

Implications of Misattribution of Arousal

The misattribution paradigm has been used as a tool by social psychologists to assess whether arousal accompanies psychological phenomena (e.g., cognitive dissonance). For students of social psychology, the message is that, consistent with many findings in social psychology, aspects of the situation can have a profound influence on individuals—in this case, on the emotions an individual experiences. Consequently, you may want to take your date to a scary movie and hope that your date will interpret his or her sweaty palms as attraction to you, but be careful, because in this context, arousal caused by actual feelings of attraction may also be attributed to fear in response to the scary film.

References:

- Sinclair, R. C., Hoffman, C., Mark, M. M., Martin, L. L., & Pickering, T. L. (1994). Construct accessibility and the misattribution of arousal: Schachter and Singer revisited. Psychological Science, 5, 15-19.

- Zanna, M. P., & Cooper, J. (1974). Dissonance and the pill: An attribution approach to studying the arousal properties of dissonance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 29, 703-709.

- Zillmann, D. (1983). Transfer of excitation in emotional behavior. In J. T. Cacioppo & R. E. Petty (Eds.), Social psychophysiology: A sourcebook. New York: Guilford Press.

- Open Course

Misattribution of Arousal

In this video I explain the idea of misattribution of arousal ; when people misinterpret their physiological arousal, which may cause them to mislabel their emotional experience. I explain how this was demonstrated in Schachter & Singer’s study (discussed in the previous video) as well as in Stuart Valins’s study of false heart-beat feedback. The most famous example of misattribution of arousal comes from Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron ‘s study of male responses to a female interviewer differing whether they met her on the Capilano suspension bridge or on solid ground.

Stuart Valins (1966) Cognitive Effects of False Heart-Rate Feedback: https://www.researchgate.net/publicat…

Radiolab Live – Tell-Tale Hearts – http://www.radiolab.org/story/radiola…

Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron (1974) Some evidence for heightened sexual attraction under conditions of high anxiety: http://gaius.fpce.uc.pt/niips/novopla…

Don’t forget to subscribe to the channel to see future videos! Have questions or topics you’d like to see covered in a future video? Let me know by commenting or sending me an email!

Video Transcript

Hi, I’m Michael Corayer and this is Psych Exam Review. In this video we’re going to look at the idea of misattribution of arousal. So in the previous video I talked about theories of emotion and I ended by talking about the Schachter-Singer theory of emotion which is also known as Two-Factor theory and the basic idea of Two-Factor theory is that our emotional experience is the result of a combination of our physiological activity and our interpretation of that activity and the situation that we’re in.

What this means is that it’s possible for us to misinterpret things, to misinterpret the cause of that physiological activity and as a result we might mislabel our emotional experience. Now this was demonstrated in the experiment I described by Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer in that some of the participants were misinformed about the effects of an injection that they received. So the participants had received an injection of epinephrine or adrenaline, and some of them were told the truth about what this injection was going to do to them and others were misinformed. And then later what we saw was that the participants labeled their emotional state differently depending on whether they were well-informed or misinformed about the source of their physiological activity.

Now this misattribution of arousal was also demonstrated in a study by Stuart Valins , and Valins was actually a student of Stanley Schachter’s, and one study that Valins did had males listen to a heartbeat and they believed that they were listening to their own heartbeat. And while they were listening to their heartbeat they were asked to rate their attraction to images of semi-nude women. What Valins found was that if the researchers manipulated the speed of the heartbeat that the males were listening to, so if they’re looking at these pictures and they hear the heartbeats speeding up, they actually misinterpreted this as thinking their own heart was speeding up. And as a result they rated those images as being more attractive. They felt more attraction to those women because they thought “my heart’s beating faster, that must clearly be a sign that I really like what I’m seeing”.

Now this was also demonstrated inadvertently in 2015 during a recording of the podcast Radiolab by WNYC. So they were doing a live podcast recording with a live audience and this podcast featured a loud heartbeat sound throughout the podcast which was playing in the background of a story that was being told. And what they found was that some of the listeners actually started feeling dizzy from hearing this heart rate that was accelerating and some people actually fainted from hearing this. And this shows this possibility to misinterpret the source of physiological activity. Now of course in this case the participants even knew that the heart that they were hearing was not their own and yet it still had this powerful effect.

Now probably the most famous example of misattribution of arousal is a study conducted by Donald Dutton and Arthur Aaron in 1974 . In this study Dutton and Aaron had males interviewed by a female in Capilano Park in Vancouver and in some cases the female interviewed the male subjects while they were standing on the Capilano Suspension Bridge and in other cases the men were interviewed by the same female interviewer but they were standing on stable ground. At the end of the interview, she sort of gives them her phone number and says you know “you can give me a call if you have any questions”.

And what Dutton and Aaron found was that the men who met her while they were standing on the suspension bridge were more likely to call than the men who met her while they were standing on solid ground. Now to give you an idea of why this bridge would have this potential effect on men calling this woman back, we’ll take a look at the Capilano Suspension Bridge. So here’s a picture of it here and you can see that it’s probably a bit of a physiologically arousing experience to be standing on this bridge. To give you a sense of scale there you can see that those are two people standing on the bridge, so it’s quite high up and it’s still shaking.

The idea is that the men were misinterpreting their physiological arousal. The bridge was the cause of their elevated heart rate and their sweaty palms but they’re talking to this woman and they’re thinking you know “my heart’s pounding and I’m sweating, like, man, I must really be attracted to her” right? So they misinterpreted this and therefore they were more likely to try to get in touch with her after the interview was over. Ok, so hopefully that helps you to understand this idea of misattribution of arousal. I hope you found this helpful, if so, please like the video and subscribe to the channel for more. Thanks for watching!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Some evidence for heightened sexual attraction under conditions of high anxiety

- PMID: 4455773

- DOI: 10.1037/h0037031

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- The aggression-inhibiting influence of heightened sexual arousal. Baron RA. Baron RA. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1974 Sep;30(3):318-22. doi: 10.1037/h0036887. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1974. PMID: 4459439 No abstract available.

- Role playing as a source of self-observation and behavior change. Kopel SA, Arkowitz HS. Kopel SA, et al. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1974 May;29(5):677-86. doi: 10.1037/h0036675. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1974. PMID: 4833429 No abstract available.

- Effects of varying intensity of attack and fear arousal on the intensity of counter aggression. Knott PD, Drost BA. Knott PD, et al. J Pers. 1972 Mar;40(1):27-37. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1972.tb00646.x. J Pers. 1972. PMID: 5013147 No abstract available.

- Thematic techniques and clinical practice. Dana RH. Dana RH. J Proj Tech Pers Assess. 1968 Jun;32(3):204-14. doi: 10.1080/0091651X.1968.10120473. J Proj Tech Pers Assess. 1968. PMID: 4385565 Review. No abstract available.

- Alcohol and tension reduction. A review. Cappell H, Herman CP. Cappell H, et al. Q J Stud Alcohol. 1972 Mar;33(1):33-64. Q J Stud Alcohol. 1972. PMID: 4551021 Review. No abstract available.

- How music-induced emotions affect sexual attraction: evolutionary implications. Marin MM, Gingras B. Marin MM, et al. Front Psychol. 2024 Apr 10;15:1269820. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1269820. eCollection 2024. Front Psychol. 2024. PMID: 38659690 Free PMC article. Review.

- Enjoying art: an evolutionary perspective on the esthetic experience from emotion elicitors. Serrao F, Chirico A, Gabbiadini A, Gallace A, Gaggioli A. Serrao F, et al. Front Psychol. 2024 Feb 26;15:1341122. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1341122. eCollection 2024. Front Psychol. 2024. PMID: 38469222 Free PMC article.

- The increasing instance of negative emotion reduce the performance of emotion recognition. Wang X, Zhao S, Pei Y, Luo Z, Xie L, Yan Y, Yin E. Wang X, et al. Front Hum Neurosci. 2023 Oct 13;17:1180533. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2023.1180533. eCollection 2023. Front Hum Neurosci. 2023. PMID: 37900730 Free PMC article.

- Facial attractiveness in the eyes of men with high arousal. Han S, Gao J, Xing W, Zhou X, Luo Y. Han S, et al. Brain Behav. 2023 Sep;13(9):e3132. doi: 10.1002/brb3.3132. Epub 2023 Jun 27. Brain Behav. 2023. PMID: 37367435 Free PMC article.

- Exploring effects of response biases in affect induction procedures. Moulds DJ, Meyer J, McLean JF, Kempe V. Moulds DJ, et al. PLoS One. 2023 May 11;18(5):e0285706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0285706. eCollection 2023. PLoS One. 2023. PMID: 37167316 Free PMC article.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Genetic Alliance

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

What “The Love Bridge” Tells Us About How Thoughts and Emotions Interact

How much control do you have over your emotions?

Have you ever wondered why one person can speak in public without apparent nerves while another crumples under pressure?

Or why one elite athlete can shake off their nerves to win Olympic gold while another chokes?

Even with ample experience some people never seem to learn to cope with their emotions.

A key insight comes from a controversial psychology study carried out on a rickety bridge by Dutton and Aron (1973) .

The love bridge

Men crossing the bridge were approached by an attractive woman who asked them to fill out a survey. The men were chosen because they were known to be nervous and this was exaggerated by the fact the bridge was swaying, its handrails were very low and there was a 230-foot drop to the river below.

After the men filled out the survey the woman gave them her number and said they could call her if they wanted the study explained in more detail.

A little further up men crossing another bridge were also being approached by a female researcher half-way across. The difference was that this bridge was sturdy, did not sway and was only a few feet above a small stream.

One of the key tests was: how many people would call up the attractive woman?

On the stable, safe bridge only 2 out of the 16 participants called. But, on the rickety bridge, 9 out of 18 called. So something about the rickety bridge made people more likely to call.

Fear transformed into attraction?

Dutton and Aron’s explanation was that it’s how we label the feelings we have that’s important, not just the feelings themselves. In this experiment men on the rickety bridge were more stressed and jittery than those on the stable bridge. And the argument is that they interpreted these bodily feelings as attraction, leading them to be more likely to make the call.

So: fear had been transformed into attraction.

This explanation is now controversial because subsequent studies have found that it’s rare to be able to reinterpret a negative emotion like fear into a positive one like attraction. Indeed some studies have specifically shown it can’t be done ( Zanna et al., 1976 ).

However, we can reinterpret one positive emotion into a different positive emotion, and the same for negative emotions.

Certainly neutral bodily feelings can be interpreted either way. That’s why you can have a strong cup of coffee and the arousing effect might contribute to either elation or irritation, depending on how your day is going.

For a more extreme example think about the physical feeling you get on a roller-coaster. It’s not dissimilar from being mugged. You sweat, the knees wobble, the heart races and the bowels loosen. But one experience people will pay for and the other everyone would pay to avoid.

Of course the aftermath of each experience and the interpretation is quite different.

Going back to the original questions: the speaker who tries to reinterpret their nerves as excitement and anticipation is likely to do better than one who thinks of them as signals to run away and hide.

In the same way the athlete who deals with performance anxiety by trying to channel it into their race will do better than the athlete who allows it to overwhelm them.

Our emotions aren’t just things that happen inside us which bubble up from the deep over which we have little or no control. Like conscious thoughts their effect on our behaviour depends on how we interpret them.

Emotions aren’t the opposite of rationality, they are part and parcel of rationality and do respond to how we think. While Dutton and Aron’s experiment may have been flawed, the motivating idea behind their experiment was not: how we label and interpret our feelings can fundamentally change our experience of them.

Image credits: Jamie Hladky & _chrisUK

Author: Dr Jeremy Dean

Psychologist, Jeremy Dean, PhD is the founder and author of PsyBlog. He holds a doctorate in psychology from University College London and two other advanced degrees in psychology. He has been writing about scientific research on PsyBlog since 2004. View all posts by Dr Jeremy Dean

Join the free PsyBlog mailing list. No spam, ever.

Misattribution of Arousal (Definition + Examples)

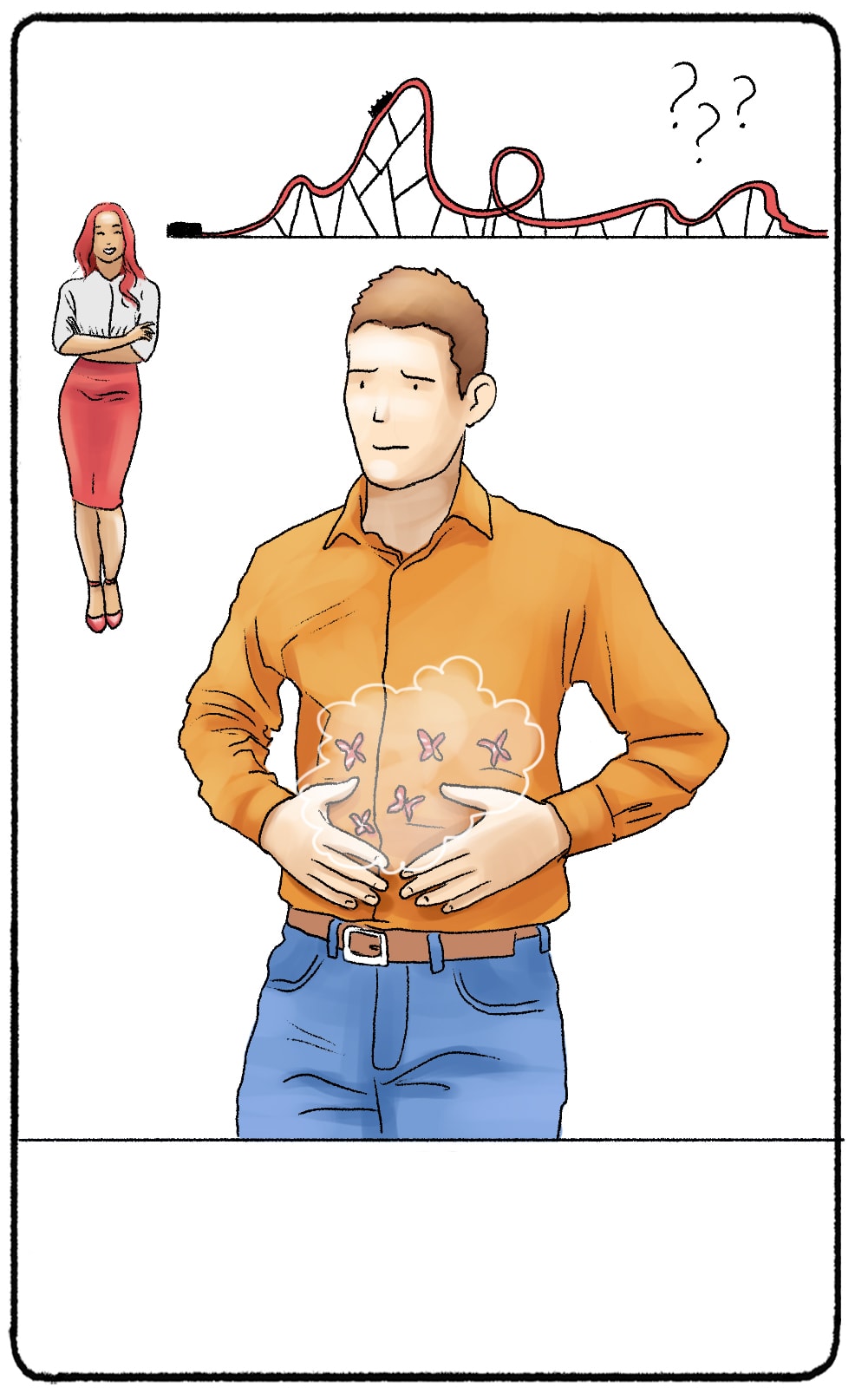

What do an amusement park, a scary movie, and a rock climbing wall have in common? Well, they all get your heart pumping. They all give you a rush of excitement at one point. And they make great first dates. Part of the reason that these three date ideas are so successful is that they get you and your date’s heart pounding. By the end of the date, you might find yourself looking at the other person with butterflies in your stomach.

These butterflies aren’t always the result of your attraction to the other person. But you might still tell yourself that you had a hot date. This is called misattribution of arousal, and it’s pretty fascinating. It’s one of the many ways that our brains might get their wires crossed or make a mistake about how we’re feeling.

What Is Misattribution of Arousal?

Misattribution of Arousal is a psychological phenomenon in which someone attributes their arousal to one stimulus, even though different stimuli may have caused it. A theme park date may excite a young man. The rollercoaster actually caused his heart to race, but he attributes the sensation to his date.

In fact, there are a ton of different ways that our brains misattribute information. “Misattribute” simply means to make a mistake. Social psychologists have studied a handful of different misattributions that distort the way that we see the world or remember things. The misattribution of arousal is particularly interesting because it involves completely arbitrary activities, like running or watching a scary movie, to how attractive someone else may seem to us.

“Arousal” doesn’t always mean sexual arousal. “To arouse” simply means to awaken or to set off a certain feeling. It could refer to the arousal of our fight-or-flight response or awaken someone from sleep.

Think about your body’s response when you’re in love or about to go on an exciting first date . Your heart is racing, your palms get sweaty, and you might feel anxious. Now think about your body’s response to a suspenseful movie or inching up a roller coaster. Same reactions, right?

We are meaning-making creatures. Our brains want an explanation for the way that we feel. On a date, we may mistake our sweaty palms and racing heart for sexual arousal, when really we are just nervous about rock climbing or seeing a horror movie.

Why Is Misattribution of Arousal Called "The Suspension Bridge Effect?"

In 1974, psychologists Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron put this theory to the test. They created an experiment in which male participants walked across two bridges. One bridge was sturdy and low to the ground. The other was suspended high in the air, so it was less sturdy.

The researchers hypothesized that the participants may misattribute their arousal from the scary bridge and think that they were more attracted to a woman who they met during the study.

They recruited the woman to meet the participants at two different parts during the test.

The first meeting was at the middle of the bridge. The woman gave the men a Thematic Apperception Test, in which they had to tell a story based on an image. The image was not meant to invoke sexual themes in the story.

The men who were on the suspension bridge were much more likely to bring in sexual themes to the story than the men who were not on the suspension bridge.

But the experiment wasn’t over. The woman also met the men at the end of the bridge or a small distance away from the end of the bridge, at a point where the men would have calmed down from the excitement of the suspension bridge. (By the way, the woman did not know the hypothesis behind the experiment.) She was instructed to give each of the men her phone number and tell them that if they had any questions, they should call her.

The same experiment was done with a male at the end of the bridge. There was no difference in whether the (presumably straight) participants called the male after the experiment was over. But there was a different when the researchers recruited a woman for the experiment. The men who met the woman immediately after leaving the suspension bridge were more likely to call the woman than the men who met her at a distance away from the suspension bridge. This proved the researcher’s hypothesis.

It Goes Both Ways

A few other experiments aimed to replicate the findings of the bridge experiment in 1974. One in particular expanded the idea of how misattribution affects attraction. In 1981, researchers published “Passionate Love and the Misattribution of Arousal.” (What a name!) The publication involved two different experiments in which men were asked to watch a video of a woman talking about themselves and rate the attractiveness of that woman. The videos were filmed in a way to make the woman appear more or less attractive.

Some men were put through exercise tests before the videos in order to create a state of arousal. The researchers found that the “aroused” men weren’t just more likely to rate the “attractive” women as more attractive than the control group. They were also more likely to rate the “unattractive” women as less attractive.

Music and Misattribution Of Arousal

There have been studies on the misattribution of arousal in women, too. (There haven’t been any significant studies on misattribution of arousal in the LGBTQ population, although this Reddit post discusses how misattribution of arousal may affect the asexual community.) One study in particular shows that different types of arousal may affect men and women.

In 2017, researchers published, “Misattribution of musical arousal increases sexual attraction towards opposite-sex faces in females.” The findings were pretty much self-explanatory. When women were aroused by listening to music, they were more likely to rate neutral male faces as attractive than women who rated the faces in silence.

How is Misattribution of Arousal Related to Self-Perception Theory?

Self-perception theory is the idea that our self-concept comes from our observations and what we make of those observations. Misattribution of arousal falls under this theory and shows that our observations may not always be "right." We determine our attraction to another person based on our interpretation of our bodily signals, whether we know where they are actually coming from or not.

You might be thinking, “I know what I’m doing for my next date!” But the real lesson regarding the misattribution of arousal should be the importance of knowing yourself and your body. You may think that the butterflies in your stomach may be from the girl you see across the room or even the food that you see in front of you. But that attractiveness may just be due to other feelings within the body. The more you can become self-aware of what is happening in your body, the less likely you will misattribute arousal and attraction.

Other Attribution Theories and Terms in Psychology

The misattribution of arousal is just one piece of a larger attribution puzzle. Attribution is a big topic in psychology. How does the mind attribute cause to actions or behaviors? What experiences or patterns of thought bring us to conclusions about why things happen? The human mind doesn’t just wonder why we feel aroused or excited. Attribution also helps us make judgments about why people do good things, evil things, and everything in between.

If you are curious about attribution or are studying attribution in your psychology classes, familiarize yourself with the following terms.

Situational Attribution

Situational attribution takes place when we attribute someone’s behavior to external factors. The following are examples of situational attribution:

- A rainy day may be the reason someone is rushed or grumpy.

- A person’s generosity may be the result of a recent lottery prize.

- When a child was young, they were told by many adults to never talk to strangers. These words echo in the person's mind every time someone tries to chat them up on the bus or at a bar.

This type of attribution suggests that the action is not a reflection of the person’s character, but their environment.

Dispositional Attribution

Dispositional attribution takes place when we attribute someone’s behavior to their character. The following are examples of dispositional attribution:

- A person is late to work because they are lazy.

- Your boss forgets to tell you about an assignment because they are manipulative and cruel.

- A billionaire donates to charity because they are a benevolent person.

This type of attribution speaks to the heart of a person’s character. The actor-observer bias is the tendency to use dispositional attribution when assessing the actions of others while using situational attribution when assessing our own actions.

Predictive Attribution

We look for patterns when we look for meaning. Predictive attribution is a type of attribution that allows us to make future predictions. For example, we may attribute an Eagles win to the fact we wore our lucky shirt, and continue to wear that lucky shirt before every game.

Explanatory Attribution

We can also attribute certain events in our lives to different factors. When we try to make sense of the world around us in this way, we are tapping into explanatory attribution. Digging deeper into this attribution, we find three explanatory styles that guide us to our ultimate conclusions.

These explanatory styles illuminate two types of attribution on different ends of a spectrum. When we learn to explain the events in our lives in positive ways, we can see the world in a more positive light and enjoy a happier life.

Let’s break down what contributes to these explanatory styles:

- Personalization (Internal vs. External Attribution)

- Permanence (Stable vs. Unstable Attribution)

- Pervasiveness (Global vs. Specific Attribution)

Personalization

Internal vs. external attribution is similar to dispositional vs. situational attribution. When we use internal attribution, we look to our character. External attribution considers outside factors. You can say that you won a contest because you are naturally talented (internal attribution) or that you lost the contest because the other contestants cheated (external attribution.)

Permanence

Are things permanent, or do they just pass us by? Stable and unstable attribution offers a different perspective. Stable attribution considers everything has a fixed, or permanent, event. Unstable attribution has a more temporary perspective. Let’s say you performed poorly on a test. You can either conclude that you will always be a failure (stable attribution) or that this test was a one-time slip-up, but you’re going to grow and do better next time (unstable attribution.)

Pervasiveness

Are events part of a worldwide pattern, or did this result just take place in one spot? How pervasive is an event? This is what global and specific attribution attempt to explain. Maybe you auditioned for an acting role and the casting director told you that you’d never make it as an actor. You can either assume that all casting directors, everywhere, feel the same way (global attribution.) Or, you can assume that the casting director’s mean words were a result of culture, the agency, or the part of town you were auditioning in (specific attribution.)

Already, you can see how different types of attribution lead to very different mindsets!

Related posts:

- Attribution Theory

- Situational Attribution (Definition + Examples)

- Fundamental Attribution Error (Definition + Examples)

- Arousal Theory of Motivation

- Dispositional Attribution (Definition + Examples)

Reference this article:

About The Author

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Misattribution of Arousal

Misattribution of arousal is a term in psychology, which describes the process whereby people make a mistake in assuming what is causing them to feel aroused.

To test the causation of misattribution of arousal, Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron (1974) conducted the following experiment. This text taken from their paper:

Male passersby were contacted either on a fear-arousing suspension bridge or a non-fear-arousing bridge by an attractive female interviewer who asked them to fill out questionnaires containing Thematic Apperception Test pictures. Sexual content of stories written by subjects on the fear-arousing bridge and tendency of these subjects to attempt postexperimental contact with the interviewer were both significantly greater. No significant differences between bridges were obtained on either measure for subjects contacted by a male interviewer. A third study manipulated anticipated shock to male subjects and an attractive female confederate independently. Anticipation of own shock but not anticipation of shock to confederate increased sexual imagery scores on the Thematic Apperception Test and attraction to the confederate. Some theoretical implications of these findings are discussed.

As the men finished the survey, the woman explained she would be available to answer any questions regarding her project, giving her phone number and name to the male subjects.

Dutton and Aron wondered if the participants were more likely to call the woman because they were physically attracted to her or not. However, Dutton and Aron had to take into consideration that some factors of the men, such as the possibility of some men already involved in a relationship or how an individual male interpreted the woman’s body gestures.

Therefore, Dutton and Aron had the woman survey the men under two conditions: immediately after they crossed a 450-foot (140 m)-long bridge or after they had crossed and had enough time to rest. In the first condition, the men who were surveyed during their cross over the bridge would have caused their arousal level to increase as they were speaking to the woman. Conditions, such as experiencing winds during their walk and the nervous feeling may have contributed to their fast paced heartbeats and rapid breathing.

In the other condition, the woman had approached the men after they had crossed the bridge. They had enough time to rest and get their heartbeat and breathing at a normal pace.

As a result, the men who were approached on the bridge were found to be more aroused and could have mistaken their arousal from the bridge for the arousal they experienced from the attractive woman’s presence. There was a large amount of those in the first condition who called the woman and asked her for a date, whereas there was a lower number in men who called the woman after crossing the bridge and resting. Similar results were found when a male approached women in the same situation.

Attraction Hacks: Misattribution of Arousal Theory

- Katherine Luong

Ready for your weekly dose of spicy psychology content? Look no further than the ~misattribution of arousal theory~. Misattribution of arousal is defined as “the idea that physiological arousal can be perceived to stem from a source that is not actually the cause of the arousal.”

The baseline assumption here is that there is always an objective biochemical cause for the sensations we feel, but it’s possible to give different cognitive labels to the same sensation—causing different conscious experiences of the same thing.

For example, nerves and excitement are two distinct feelings. One is negative, and the other is positive. But both have the same physical properties: a faster heart rate, shakiness, and a rush of adrenaline. Your cognitive interpretation of the context thus determines whether you feel good or bad about the very same sensations.

Here’s how it relates to relationship psychology: the misattribution of arousal theory can be used to induce romantic and sexual attraction in certain (heart-racing) situations—you misattribute your arousal to the person rather than the situation.

Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron conducted a famous study in 1974 commonly known as the Capilano Suspension Bridge Study , where they found that people were more attracted to a person when they met on a dangerous suspension bridge than when they met the same person on a safer, less scary bridge .

They had the same woman approach multiple men on both bridges, where she asked them to write a story and gave them her phone number for them to follow up with if they… “had any questions” 😏. They found that those who were approached on the suspension bridge were more likely to use sexual imagery in their writing sample, and more likely to call her back to ask for a date.

Dutton and Aron attributed this difference to the context: the men who were approached on the scary bridge were already nervous about their own safety—causing them to feel high heart rates, dizziness, and sweaty palms. It turns out that those same physical sensations are also present when we’re attracted to someone . And our silly little human brains can’t always tell the difference, making them believe they were more attracted to the woman than they might have been otherwise.

The takeaway is this: if you ever want to tip the scales of attraction in your favor, bring your next date to a suspension bridge. Or go skydiving. Or, you can just work out together too! Anything that raises their heart rate, whether it be fear or physical activity, can trick their brain into thinking you’re the reason that their heart is fluttering (or that they might pass out). Don’t go overboard, but keep the misattribution of arousal theory in mind to boost attraction, whether you’re trying to trick yourself or your crush.

Katherine is a Relationship Psychology Researcher on the Marriage Pact's Relationship Science Team. She can be reached at katherine ‘at’ marriagepact.com.

Don’t miss another story.

Subscribe to the Marriage Pact Newsletter for a weekly dose of Marriage Pact, delivered straight to your inbox.

You Are Not So Smart

Misattribution of arousal.

The Misconception: You always know why you feel the way you feel.

The Truth: You can experience emotional states without knowing why, even if you believe you can pinpoint the source.

The bridge is still in British Columbia, still long and scary, still sagging across the Capilano Canyon daring people to traverse it.

If you were to place the Statue of Liberty underneath the bridge, base and all, it would lightly drape across her copper shoulders. It is about as wide as a park bench for its entire suspended length, and when you try to cross, feeling it sway and rock in the wind, hearing it creak and buckle, it is difficult to take your eyes off of the rocks and roaring water two-hundred and thirty feet below – far enough for you feel in your stomach the distance between you and a messy, crumpled death. Not everyone makes it across.

In 1974, psychologists Art Aron and Donald Dutton hired a woman to stand in the middle of this suspension bridge. As men passed her on their way across, she asked them if they would be willing to fill out a questionnaire. At the end of the questions, she asked them to examine an illustration of a lady covering her face and then make up a back story to explain it. She then told each man she would be more than happy to discuss the study further if he wanted to call her that night, and tore off a portion of the paper, wrote down her number, and handed it over.

The scientists knew the fear in the men’s bellies would be impossible to ignore, and they wanted to know how a brain soaking in anxiety juices would make sense of what just happened. To do this, they needed another bridge to serve as a control, one which wouldn’t produce terror, so they had their assistant go through the same routine on a wide, sturdy, wooden bridge standing fixed just a few feet off of the ground.

After running the experiment at both locations, they compared the results and found 50 percent of the men who got them digits on the dangerous suspension bridge picked up a phone and called looking for the lady of the canyon. Of the men questioned on the secure bridge, the percentage who came calling dropped to 12.5. That wasn’t the only significant difference. When they compared the stories the subjects made up about the illustration, they found the men on the scary bridge were almost twice as likely to come up with sexually suggestive narratives.

What was going on here? One bridge made men flirty and eager to follow up with female interviewers, and one did not. To make sense of it, you must understand something psychologists call arousal and how easy it is to falsely identify its source. Mistaken emotional origins can save relationships, create amorous mirages and lead you into behaviors and attitudes both sublime and hypocritical.

Arousal, in the psychological sense, is not limited to sexual situations. It can envelop you in a number of ways. You’ve felt it: increased heart rate, focused attention, sweaty palms, dry mouth, big breaths followed by bigger sighs. It is that wide-eyed, electricity in your veins feeling you get when the wind picks up and the rain begins to pour. It is a state of wakefulness, more alert and aware than normal, in which your mind is paying full attention to the moment. This isn’t the action-roll-out-of bed-feeling you get when a fire alarm snaps you out of a deep sleep. No, arousal is prolonged and total, it builds and saturates. Arousal comes from deep inside the brain, in those primal regions of the autonomic nervous system where ingoing and outgoing signals are monitored and the glass over the big fight-or-flight button waits to be smashed. You feel it as a soldier waiting to see if the next mortar has your name on it, as a musician walking on stage inside a sold-out stadium, as a crowd member elevated by a powerful speech, in a group circling a fire and singing and drumming, as a member of a congregation swimming in the Gospel and swaying with hands raised, in a couple at the center of a packed dance floor. Your eyes water with ease. You want to weep and laugh simultaneously. You could just explode.

The men on the bridge experienced this heightened state of clarity, fear, anxiety and dread, and when they met an attractive woman those feelings continued to flow into their hearts and heads, but the source got scrambled. Was it the bridge or the lady? Was she being nice, or was she interested? Why did she pick me? My heart is pounding – is she making me feel this way? When Aron and Dutton ran the bridge experiment with a male interviewer (and male subjects), the lopsided results disappeared. The men no longer considered the interviewer as a possible cause, or if they did they suppressed it. The misattribution of arousal also went away when they ran the experiment on a safe bridge. No heightened state, no need to explain it. On a hunch, Aron and Dutton decided to move the experiment away from the real world with all its uncontrollable variables and attack the puzzle from another direction in the lab.

In the lab experiment male college students entered a room full of scientific-looking electrical equipment where a researcher greeted them asking if they had seen another student wandering around. When the men said they hadn’t, the scientists pretended to go looking for the other subject and left behind reading material for the men to look over concerning learning and painful electric shocks. When the scientists felt like enough time had passed, they brought in an actress who pretended to be another student who had also volunteered for the study. The men, one at a time, would then sit beside the woman and listen as the scientists explained the subjects would soon be shocked with either a terrible, bowel-loosening megablast or a “mere tingle.” After all of this, the psychologists flipped a coin to determine who would be getting what. They weren’t actually going to shock anyone, they just wanted to scare the bejeezus out of the men. The researchers then handed over a questionnaire similar to the one from the bridge experiment, complete with the illustration interpretation portion, and told the men to work on it while they prepared the electrocution machines.

The questionnaire asked the men to rate their anxiety and their attraction to the other subject. As the scientists suspected, the results matched the bridge. The men who expected a terrible, painful future rated their anxiety and their attraction to the ladies as significantly higher than those expecting mild tingles. When it came to those narratives explaining the pictures, once again the more anxious the men, the more sexual imagery they produced.

Aron and Dutton showed when you feel aroused, you naturally look for context, an explanation as to why you feel so alive. This search for meaning happens automatically and unconsciously, and whatever answer you come up with is rarely questioned because you don’t realize you are asking. Like the men on the bridge, you sometimes make up a reason for why you feel the way you do, and then you believe your own narrative and move on. It is easy to pinpoint the source of your contorted face and toothy grin if you took peyote at Burning Man and are twirling glow sticks to the beat of a pulsating lizard-faced bassoon quartet. The source of your coursing blood is more ambiguous if you just drank a Red Bull before heading into a darkened theater to watch an action movie. You can’t know for sure it if it is the explosions or the caffeinated taurine water, but damn if this movie doesn’t rock. In many situations you either can’t know or fail to notice what got you physiologically amped, and you mistakenly attribute the source to something in your immediate environment. People, it seems, are your favorite explanations as studies show you prefer to see other human beings as the source of your heightened state of arousal when given the option. The men expecting to get electrocuted misattributed a portion of their pulse’s pace to the ladies by their sides. Aron and Dutton focused on fear and anxiety, but in the years since, research has revealed just about any emotional state can be misattributed, and this has led to important findings on how to keep a marriage together.

In 2008, psychologist James Graham at the University of North Carolina conducted a study to see what sort of activities kept partners bonded. He had 20 couples who lived together carry around digital devices while conducting their normal daily activities. Whenever the device went off, they had to use it to text back to the researchers and tell them what they were up to. They then answered a few questions about their mood and how they felt toward their partners. After over a thousand of these buzz-report-introspect-text moments, he looked over the data and found couples who routinely performed difficult tasks together as partners were also more likely to like each other. Over the course of his experiments, he found partners tended to feel closer, more attracted to and more in love with each other when their skills were routinely challenged. He reasoned the buzz you get when you break through a frustrating trial and succeed, what Graham called flow, was directly tied to bonding. Just spending time together is not enough, he said. The sort of activities you engage in are vital. Graham concluded you are driven to grow, to expand, to add to your abilities and knowledge. When you satisfy this motivation for self-expansion by incorporating aspects of your romantic partner or friend into your own skills, philosophies and self, it does more to strengthen your bond than any other act of love. This opens the door to one of the best things about misattribution of emotion. If, like those in the study, you persevere through a challenge – be it remodeling a kitchen yourself or learning how to Dougie – that glowing feeling of becoming more wise, that buoyant sense of self-expansion will be partially misattributed to the presence of the other person. You become conditioned over time to see the relationship itself as a source for those sorts of emotions, and you will become less likely to want to sever your bond with the other party. In the beginning, just learning how to relate to the other person and interpret their non-verbal cues, emotional swings and strange food aversions is an exercise in self-expansion. The frequency of novelty can diminish as the relationship ages and you settle into routines. The bond can seem to weaken. To build it up again you need adversity, even if simulated. Taking ballroom dancing lessons or teaming up against friends in Trivial Pursuit are more likely to keep the flame flickering than wine and Marvin Gaye.

I think falling in love occurs under the right circumstances and it is not a rational process, but it’s a predictable process. – Psychologist Art Aron

The arousal you are prone to misattributing can also come from within, especially if you find yourself on questionable moral ground. Mark Zanna and Joel Cooper in 1978 gave placebo pills to a group of subjects. They told half of the pill takers the drug would make them feel relaxed, and they told the other half it would make them feel tense. They then asked the subjects to write an essay explaining why free speech should be banned. Most people were reluctant and felt terrible about expressing an opinion counter to their true beliefs. When the researchers gave all the participants a chance to go back and change their papers, the ones who thought they had taken a downer were far more likely to take them up on the offer. The ones who thought they took a speedy pill assumed the heat under their collars was from the drug instead of their own cognitive dissonance, so they didn’t feel the need to change their positions. The other group had no scapegoat for their emotional states, so they wanted to rewrite the paper because they suspected it would ease their minds and bring their arousal back down to normal. Cognitive dissonance, behaving in a way which seems to run counter to your beliefs, cranks up arousal in a way that feels awful. The subjects in the Zanna and Cooper experiment wanted to alleviate this, but only those who thought they took the downer could pinpoint the source of their mental discomfort. For the other group, the fake upper served as a red herring throwing them off the trail back to their own negative emotions.

Misattribution of arousal falls under the self-perception theory. This theory goes back as far as William James, one of the founders of psychology. It posits your attitudes are shaped by observing your own behavior and trying to make sense of it. For instance, James would say if you saw a cricket on your arm and then flailed about rubbing your body up and down while screaming incoherently, you would later assume you had experienced fear and might then believe you were afraid of crickets. Self-perception theory says you look back on a situation like this as if in an audience trying to understand your own motivations. Sometimes, you jump to conclusions without all the facts. As with many theories, there is much research left to be done and plenty of debate, but in many ways James was right. You often do act as observer of your actions, a witness to your thoughts, and you form beliefs about your self based on those observations. Psychologist Fritz Strack devised a simple experiment in 1988 in which he had subjects hold a pen straight out between their incisors and bare their teeth as they read cartoon strips. The subjects tended to find the cartoons funnier than when they held the pen between their lips instead. Between the teeth, some of the muscles used for smiling were contracted, and between the lips they contracted some of the muscles used for frowning. He concluded the subjects felt themselves smiling and decided somewhere deep in their minds they must be enjoying the comics. When they felt themselves frowning, they assumed they thought the comics were dull. In a similar experiment in 1980 by Gary Wells and Richard Petty at the University of Alberta subjects were asked to test out headphones by either nodding or shaking their heads while listening to a pundit delivering an editorial. Sure enough, when questioned later the nodders tended to agree with the opinion of the speaker more than the shakers. In 2003, Jens Förster at International University Bremen asked volunteers to rate food items as they moved across a large screen. Sometimes the food names moved up and down, and sometimes side to side, thus producing unconscious nodding or head shaking. As in the pundit study, people tended to say they preferred the foods which made them nod unless they were gross. In Förster’s and other similar studies, positive and negative opinions became stronger, but if a person hated broccoli, for example, no amount of head nodding would change their mind.

Arousal can fill up the spaces in your brain when you least expect it. It could be a rousing movie trailer or a plea for mercy from a distant person reaching out over YouTube. Like a coterie of prairie dogs standing alert as if living periscopes, your ancestors were built to pay attention when it mattered, but with cognition comes pattern recognition and all the silly ways you misinterpret your inputs. The source of your emotional states is often difficult or impossible to detect. The time to pay attention can pass, or the details become lodged in a place underneath consciousness. In those instances you feel, but you know not why. When you find yourself in this situation you tend to lock onto a target, especially if there is another person who fits with the narrative you are about to spin. It feels good to assume you’ve discovered what is causing you to feel happy, to feel rejected, to feel angry or lovesick. It helps you move forward. Why question it?

The research into arousal says you are bad at explaining yourself to yourself, but it sheds light on why so many successful dates include roller-coasters, horror films and conversations over coffee. If you want to get things rolling with a romantic interest you would be better served by bungee jumping or scuba diving, ice skating or rock climbing than candlelit dinners. No doubt, trapeze artists must have complicated and compelling love lives.

There is a reason playful wrestling can lead to passionate kissing, why a great friend can turn a heaving cry into a belly laugh. There is a reason why great struggle brings you closer to friends, family and lovers. There is a reason why Rice Krispies commercials show moms teaching children how to make treats in crisp black-and-white while Israel Kamakawiwo’ole sings Somewhere Over the Rainbow . When you want to know why you feel the way you do but are denied the correct answer, you don’t stop searching. You settle on something – the person beside you, the product in front of you, the drug in your brain. You don’t always know the right answer, but when you are flirting over a latte don’t point it out.

If you buy one book this year…well, I suppose you should get something you’ve had your eye on for a while. But, if you buy two or more books this year, might I recommend one of them be a celebration of self delusion? Give the gift of humility (to yourself or someone else you love). Watch the trailer.

Order now: Amazon – Barnes and Noble – iTunes – Books A Million

Video of Aron discussing bridge experiment

A followup to the pen in the mouth study

The food and head nodding study

The adversity and bonding study

The cognitive dissonance study

A meta-analysis of the Schachter theory of emotion

Where the body goes, the mind follows

Isreal Kamakawiwo’ole’s Somewhere Over the Rainbow

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Begin typing your search above and press return to search. Press Esc to cancel.

Discover more from You Are Not So Smart

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

Whistling Vivaldi

Claude steele.

Ask LitCharts AI: The answer to your questions

| Summary & Analysis |

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron's study (1974) [3] ... The experiment confirmed the researcher's hypothesis that individuals in a neutral aroused state were more likely to rate a target as attractive than an unaroused individual. White, Fishbein, and Rutsein hypothesized that the polarity of an individual's arousal could influence the impact of ...

The experiment that Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron conducted is commonly known as the Capilano Suspension Bridge study. As the name suggests, these two psychologists used two bridges to prove their point. The first bridge was small, solid, and modern. The other, on the other hand, was located on the Capilano Canyon, 230 feet above the ground.

Dutton and Aron, 1974: Bridge Study. The original study that demonstrated misattribution of arousal was performed by two psychologists in 1974, Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron. They published the results in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. The article is called SOME EVIDENCE FOR HEIGHTENED SEXUAL ATTRACTION UNDER CONDITIONS OF ...

G. Dutton, Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver 8, British Columbia, ... Experiment 1 is an attempt to verify this proposed emo-tion-sexual attraction link in a natural set- ... 512 DONALD G. BUTTON AND ARTHUR P. ARON sheet of paper, wrote down her name and phone number, and invited each subject to call, if he ...

The Misattribution of Arousal, a concept explored by psychologists Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron in the 1970s, has significantly contributed to our understanding of emotional perception and cognitive processes. This influential research aimed to understand how individuals misinterpret physiological arousal, attributing it to the wrong source ...

In a landmark study in 1974, Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron studied whether attraction would be more likely to develop in the context of anxiety-inducing (or arousal-inducing) situations. ... In their experiment, male participants were approached after crossing one of two bridges: a stable, modern bridge close to the ground or a high, 450-foot ...

85 male passersby were contacted either on a fear-arousing suspension bridge or a non-fear-arousing bridge by an attractive female interviewer who asked them to fill out questionnaires containing Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) pictures. Sexual content of stories written by Ss on the fear-arousing bridge and tendency of these Ss to attempt postexperimental contact with the interviewer were ...

The suspension bridge experiment was conducted by Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron in 1974, in order to demonstrate a process where people apparently misjudge the cause of a high level of arousal. The results of the experiment showed that the men who were approached by an attractive woman on a less secure bridge were found to experience a higher ...

In a classic experiment conducted by Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron in 1974, the misattribution of arousal effect was shown to even affect feelings of attraction. In this experiment, an attractive female experimenter approached men as they crossed either a high, rickety suspension bridge or a low, safe bridge at a popular tourist site in ...

Don Dutton and Arthur Aron were looking to research the effect a person's physical state had on romantic attraction. The two brainstormed ideas for an experiment in a location where a distressed person might come across a person of the opposite sex. Aron suggested something involving a dentist's office. Dutton thought the 137-metre-long ...

Psychologists Donald G. Dutton and Arthur P. Aron wanted to use a natural setting that would induce physiological arousal. In this experiment, they had male participants walk across two different styles of bridges. One bridge was a very scary (arousing) suspension bridge, which was very narrow and suspended above a deep ravine. The second ...

Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron (1974) ... Now this was demonstrated in the experiment I described by Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer in that some of the participants were misinformed about the effects of an injection that they received. So the participants had received an injection of epinephrine or adrenaline, and some of them were told the ...

D G Dutton, A P Aron. PMID: 4455773 DOI: 10.1037/h0037031 No abstract available. MeSH terms Adolescent Adult Anxiety Arousal Electroshock Emotions* Fear ...

Dutton and Aron's explanation was that it's how we label the feelings we have that's important, not just the feelings themselves. In this experiment men on the rickety bridge were more stressed and jittery than those on the stable bridge. And the argument is that they interpreted these bodily feelings as attraction, leading them to be ...

In 1974, psychologists Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron put this theory to the test. They created an experiment in which male participants walked across two bridges. ... A few other experiments aimed to replicate the findings of the bridge experiment in 1974. One in particular expanded the idea of how misattribution affects attraction. In 1981, ...

Accounts of falling in love were obtained from three samples: (a) lengthy accounts from fifty undergraduates who had fallen in love in the last 8 months; (b) brief accounts from 100 adult nonstudents, which were compared to 100 brief falling-in-friendship accounts from the same population; and (c) questionnaire responses about falling-in-love experiences from 277 undergraduates, which were ...

Misattribution of arousal is a term in psychology, which describes the process whereby people make a mistake in assuming what is causing them to feel aroused. Experiment. To test the causation of misattribution of arousal, Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron (1974) conducted the following experiment. This text taken from their paper:

Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron conducted a famous study in 1974 commonly known as the Capilano Suspension Bridge Study, ... Dutton and Aron attributed this difference to the context: the men who were approached on the scary bridge were already nervous about their own safety—causing them to feel high heart rates, dizziness, and sweaty palms ...

When Aron and Dutton ran the bridge experiment with a male interviewer (and male subjects), the lopsided results disappeared. The men no longer considered the interviewer as a possible cause, or if they did they suppressed it. The misattribution of arousal also went away when they ran the experiment on a safe bridge.

The social psychologists Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron conducted an experiment in which they asked male students to walk across a narrow, rickety bridge. Then, each student completed a questionnaire with an attractive female interviewer, who then gave the student her phone number and invited him to call her if he had any questions.

In 1974, social psychologists Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron conducted a well-known experiment on the bridge. Men approached by a female researcher on the bridge were more likely to call her later than men approached on a more solid bridge across the river.

This concept was tested through an experiment by Donald Dutton and Arthur Aron not long after the Schachter-Singer theory was introduced. In this experiment, men were instructed to walk across ...

Short talk about the famous psychological experiment of Douglas Dutton and Arthur Aron in which males passing a high anxiety inducing suspension bridge were asked to write a short story about a woman..