- What is Strategy?

- Business Models

- Developing a Strategy

- Strategic Planning

- Competitive Advantage

- Growth Strategy

- Market Strategy

- Customer Strategy

- Geographic Strategy

- Product Strategy

- Service Strategy

- Pricing Strategy

- Distribution Strategy

- Sales Strategy

- Marketing Strategy

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Organizational Strategy

- HR Strategy – Organizational Design

- HR Strategy – Employee Journey & Culture

- Process Strategy

- Procurement Strategy

- Cost and Capital Strategy

- Business Value

- Market Analysis

- Problem Solving Skills

- Strategic Options

- Business Analytics

- Strategic Decision Making

- Process Improvement

- Project Planning

- Team Leadership

- Personal Development

- Leadership Maturity Model

- Leadership Team Strategy

- The Leadership Team

- Leadership Mindset

- Communication & Collaboration

- Problem Solving

- Decision Making

- People Leadership

- Strategic Execution

- Executive Coaching

- Strategy Coaching

- Business Transformation

- Strategy Workshops

- Leadership Strategy Survey

- Leadership Training

- Who’s Joe?

“A fact is a simple statement that everyone believes. It is innocent, unless found guilty. A hypothesis is a novel suggestion that no one wants to believe. It is guilty until found effective.”

– Edward Teller, Nuclear Physicist

During my first brainstorming meeting on my first project at McKinsey, this very serious partner, who had a PhD in Physics, looked at me and said, “So, Joe, what are your main hypotheses.” I looked back at him, perplexed, and said, “Ummm, my what?” I was used to people simply asking, “what are your best ideas, opinions, thoughts, etc.” Over time, I began to understand the importance of hypotheses and how it plays an important role in McKinsey’s problem solving of separating ideas and opinions from facts.

What is a Hypothesis?

“Hypothesis” is probably one of the top 5 words used by McKinsey consultants. And, being hypothesis-driven was required to have any success at McKinsey. A hypothesis is an idea or theory, often based on limited data, which is typically the beginning of a thread of further investigation to prove, disprove or improve the hypothesis through facts and empirical data.

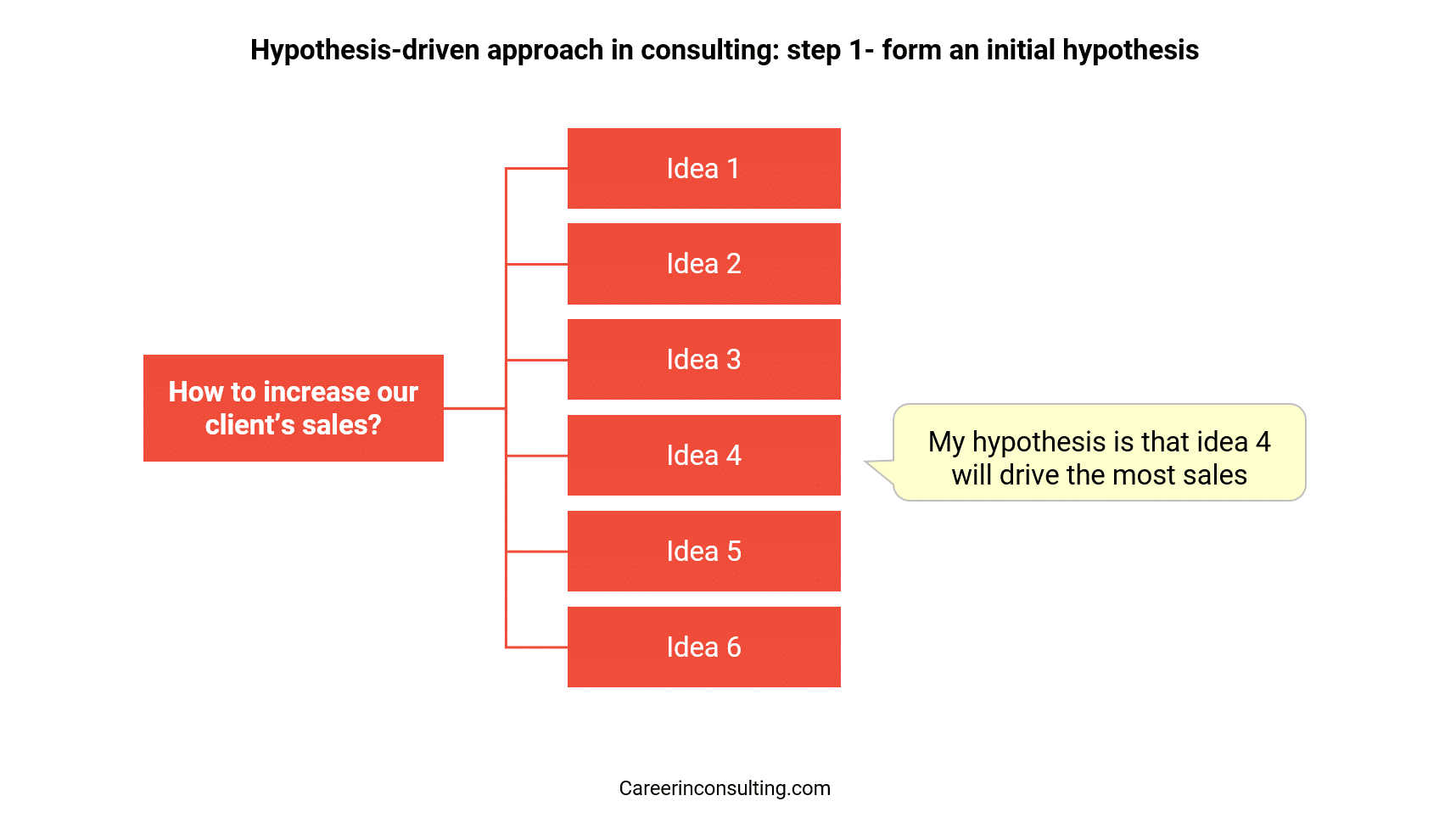

The first step in being hypothesis-driven is to focus on the highest potential ideas and theories of how to solve a problem or realize an opportunity.

Let’s go over an example of being hypothesis-driven.

Let’s say you own a website, and you brainstorm ten ideas to improve web traffic, but you don’t have the budget to execute all ten ideas. The first step in being hypothesis-driven is to prioritize the ten ideas based on how much impact you hypothesize they will create.

The second step in being hypothesis-driven is to apply the scientific method to your hypotheses by creating the fact base to prove or disprove your hypothesis, which then allows you to turn your hypothesis into fact and knowledge. Running with our example, you could prove or disprove your hypothesis on the ideas you think will drive the most impact by executing:

1. An analysis of previous research and the performance of the different ideas 2. A survey where customers rank order the ideas 3. An actual test of the ten ideas to create a fact base on click-through rates and cost

While there are many other ways to validate the hypothesis on your prioritization , I find most people do not take this critical step in validating a hypothesis. Instead, they apply bad logic to many important decisions . An idea pops into their head, and then somehow it just becomes a fact.

One of my favorite lousy logic moments was a CEO who stated,

“I’ve never heard our customers talk about price, so the price doesn’t matter with our products , and I’ve decided we’re going to raise prices.”

Luckily, his management team was able to do a survey to dig deeper into the hypothesis that customers weren’t price-sensitive. Well, of course, they were and through the survey, they built a fantastic fact base that proved and disproved many other important hypotheses.

Why is being hypothesis-driven so important?

Imagine if medicine never actually used the scientific method. We would probably still be living in a world of lobotomies and bleeding people. Many organizations are still stuck in the dark ages, having built a house of cards on opinions disguised as facts, because they don’t prove or disprove their hypotheses. Decisions made on top of decisions, made on top of opinions, steer organizations clear of reality and the facts necessary to objectively evolve their strategic understanding and knowledge. I’ve seen too many leadership teams led solely by gut and opinion. The problem with intuition and gut is if you don’t ever prove or disprove if your gut is right or wrong, you’re never going to improve your intuition. There is a reason why being hypothesis-driven is the cornerstone of problem solving at McKinsey and every other top strategy consulting firm.

How do you become hypothesis-driven?

Most people are idea-driven, and constantly have hypotheses on how the world works and what they or their organization should do to improve. Though, there is often a fatal flaw in that many people turn their hypotheses into false facts, without actually finding or creating the facts to prove or disprove their hypotheses. These people aren’t hypothesis-driven; they are gut-driven.

The conversation typically goes something like “doing this discount promotion will increase our profits” or “our customers need to have this feature” or “morale is in the toilet because we don’t pay well, so we need to increase pay.” These should all be hypotheses that need the appropriate fact base, but instead, they become false facts, often leading to unintended results and consequences. In each of these cases, to become hypothesis-driven necessitates a different framing.

• Instead of “doing this discount promotion will increase our profits,” a hypothesis-driven approach is to ask “what are the best marketing ideas to increase our profits?” and then conduct a marketing experiment to see which ideas increase profits the most.

• Instead of “our customers need to have this feature,” ask the question, “what features would our customers value most?” And, then conduct a simple survey having customers rank order the features based on value to them.

• Instead of “morale is in the toilet because we don’t pay well, so we need to increase pay,” conduct a survey asking, “what is the level of morale?” what are potential issues affecting morale?” and what are the best ideas to improve morale?”

Beyond, watching out for just following your gut, here are some of the other best practices in being hypothesis-driven:

Listen to Your Intuition

Your mind has taken the collision of your experiences and everything you’ve learned over the years to create your intuition, which are those ideas that pop into your head and those hunches that come from your gut. Your intuition is your wellspring of hypotheses. So listen to your intuition, build hypotheses from it, and then prove or disprove those hypotheses, which will, in turn, improve your intuition. Intuition without feedback will over time typically evolve into poor intuition, which leads to poor judgment, thinking, and decisions.

Constantly Be Curious

I’m always curious about cause and effect. At Sports Authority, I had a hypothesis that customers that received service and assistance as they shopped, were worth more than customers who didn’t receive assistance from an associate. We figured out how to prove or disprove this hypothesis by tying surveys to transactional data of customers, and we found the hypothesis was true, which led us to a broad initiative around improving service. The key is you have to be always curious about what you think does or will drive value, create hypotheses and then prove or disprove those hypotheses.

Validate Hypotheses

You need to validate and prove or disprove hypotheses. Don’t just chalk up an idea as fact. In most cases, you’re going to have to create a fact base utilizing logic, observation, testing (see the section on Experimentation ), surveys, and analysis.

Be a Learning Organization

The foundation of learning organizations is the testing of and learning from hypotheses. I remember my first strategy internship at Mercer Management Consulting when I spent a good part of the summer combing through the results, findings, and insights of thousands of experiments that a banking client had conducted. It was fascinating to see the vastness and depth of their collective knowledge base. And, in today’s world of knowledge portals, it is so easy to disseminate, learn from, and build upon the knowledge created by companies.

NEXT SECTION: DISAGGREGATION

MCKINSEY PROBLEM SOLVING COURSE - LEARN MORE & ENROLL

Download strategy presentation templates.

THE $150 VALUE PACK - 600 SLIDES 168-PAGE COMPENDIUM OF STRATEGY FRAMEWORKS & TEMPLATES 186-PAGE HR & ORG STRATEGY PRESENTATION 100-PAGE SALES PLAN PRESENTATION 121-PAGE STRATEGIC PLAN & COMPANY OVERVIEW PRESENTATION 114-PAGE MARKET & COMPETITIVE ANALYSIS PRESENTATION 18-PAGE BUSINESS MODEL TEMPLATE

JOE NEWSUM COACHING

EXECUTIVE COACHING STRATEGY COACHING ELEVATE360 BUSINESS TRANSFORMATION STRATEGY WORKSHOPS LEADERSHIP STRATEGY SURVEY & WORKSHOP STRATEGY & LEADERSHIP TRAINING

THE LEADERSHIP MATURITY MODEL

Explore other types of strategy.

BIG PICTURE WHAT IS STRATEGY? BUSINESS MODEL COMP. ADVANTAGE GROWTH

TARGETS MARKET CUSTOMER GEOGRAPHIC

VALUE PROPOSITION PRODUCT SERVICE PRICING

GO TO MARKET DISTRIBUTION SALES MARKETING

ORGANIZATIONAL ORG DESIGN HR & CULTURE PROCESS PARTNER

EXPLORE THE TOP 100 STRATEGIC LEADERSHIP COMPETENCIES

TYPES OF VALUE MARKET ANALYSIS PROBLEM SOLVING

OPTION CREATION ANALYTICS DECISION MAKING PROCESS TOOLS

PLANNING & PROJECTS PEOPLE LEADERSHIP PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT

Career in Consulting

Hypothesis-driven approach: the definitive guide

Imagine you are walking in one of McKinsey’s offices.

Around you, there are a dozen of busy consultants.

The word “hypothesis” would be one of the words you would hear the most.

Along with “MECE” or “what’s the so-what?”.

This would also be true in any BCG, Bain & Company office or other major consulting firms.

Because strategy consultants are trained to use a hypothesis-driven approach to solve problems.

And as a candidate, you must demonstrate your capacity to be hypothesis-driven in your case interviews .

There is no turnaround:

If you want a consulting offer, you MUST know how to use a hypothesis-driven approach .

Like a consultant would be hypothesis-driven on a real project for a real client?

Hell, no! Big mistake!

Because like any (somehow) complex topics in life, the context matters.

What is correct in one context becomes incorrect if the context changes.

And this is exactly what’s happening with using a hypothesis-driven approach in case interviews.

This should be different from the hypothesis-driven approach used by consultant solving a problem for a real client .

And that’s why many candidates get it wrong (and fail their interviews).

They use a hypothesis-driven approach like they were already a consultant.

Thus, in this article, you’ll learn the correct definition of being hypothesis-driven in the context of case interviews .

Plus, you’ll learn how to use a hypothesis in your case interviews to “crack the case”, and more importantly get the well-deserved offer!

Ready? Let’s go. It will be super interesting!

Table of Contents

The wrong hypothesis-driven approach in case interviews.

Let’s start with a definition:

Hypothesis-driven thinking is a problem-solving method whereby you start with the answer and work back to prove or disprove that answer through fact-finding.

Concretely, here is how consultants use a hypothesis-driven approach to solve their clients’ problems:

- Form an initial hypothesis, which is what they think the answer to the problem is.

- Craft a logic issue tree , by asking themselves “what needs to be true for the hypothesis to be true?”

- Walk their way down the issue tree and gather the necessary data to validate (or refute) the hypothesis.

- Reiterate the process from step 1 – if their first hypothesis was disproved by their analysis – until they get it right.

With this answer-first approach, consultants do not gather data to fish for an answer. They seek to test their hypotheses , which is a very efficient problem-solving process.

The answer-first thinking works well if the initial hypothesis has been carefully formed.

This is why – in top consulting firms like McKinsey , BCG , or Bain & Company – the hypothesis is formed by a Partner with 20+ years of work experience.

And this is why this is NOT the right approach for case interviews.

Imagine a candidate doing a case interview at McKinsey and using answer-first thinking.

At the beginning of a case, this candidate forms a hypothesis (a potential answer to the problem), builds a logic tree, and gathers data to prove the hypothesis.

Here, there are two options:

The initial hypothesis is right

The initial hypothesis is wrong

If the hypothesis is right, what does it mean for the candidate?

That the candidate was lucky.

Nothing else.

And it certainly does not prove the problem-solving skills of this candidate (which is what is tested in case interviews).

Now, if the hypothesis is wrong, what’s happening next?

The candidate reiterates the process.

Imagine how disorganized the discussion with the interviewer can be.

Most of the time, such candidates cannot form another hypothesis, the case stops, and the candidate feels miserable.

This leads us to the right hypothesis-driven approach for case interviews.

The right hypothesis-driven approach in case interviews

To make my point clear between the wrong and right approach, I’ll take a non-business example.

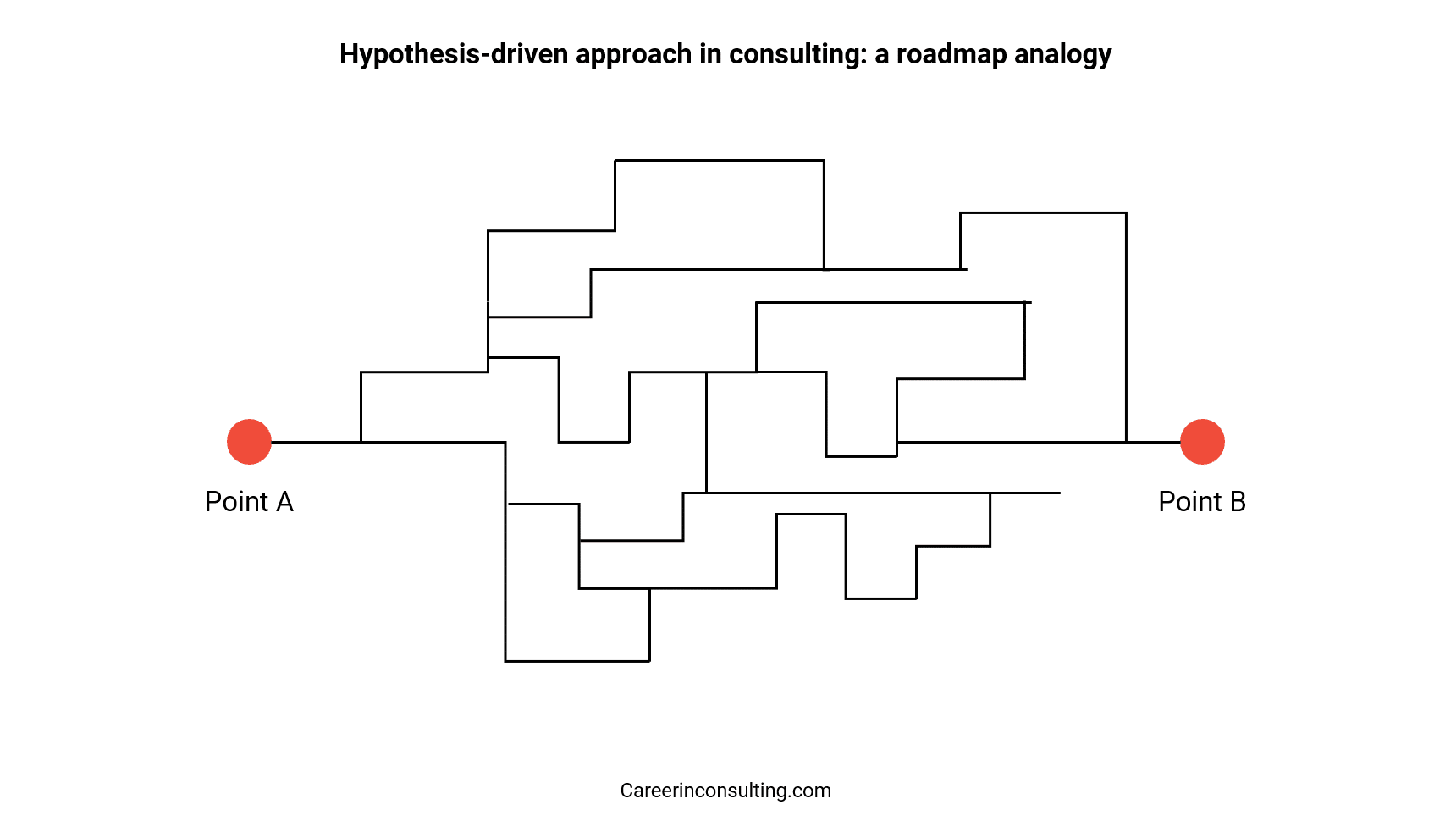

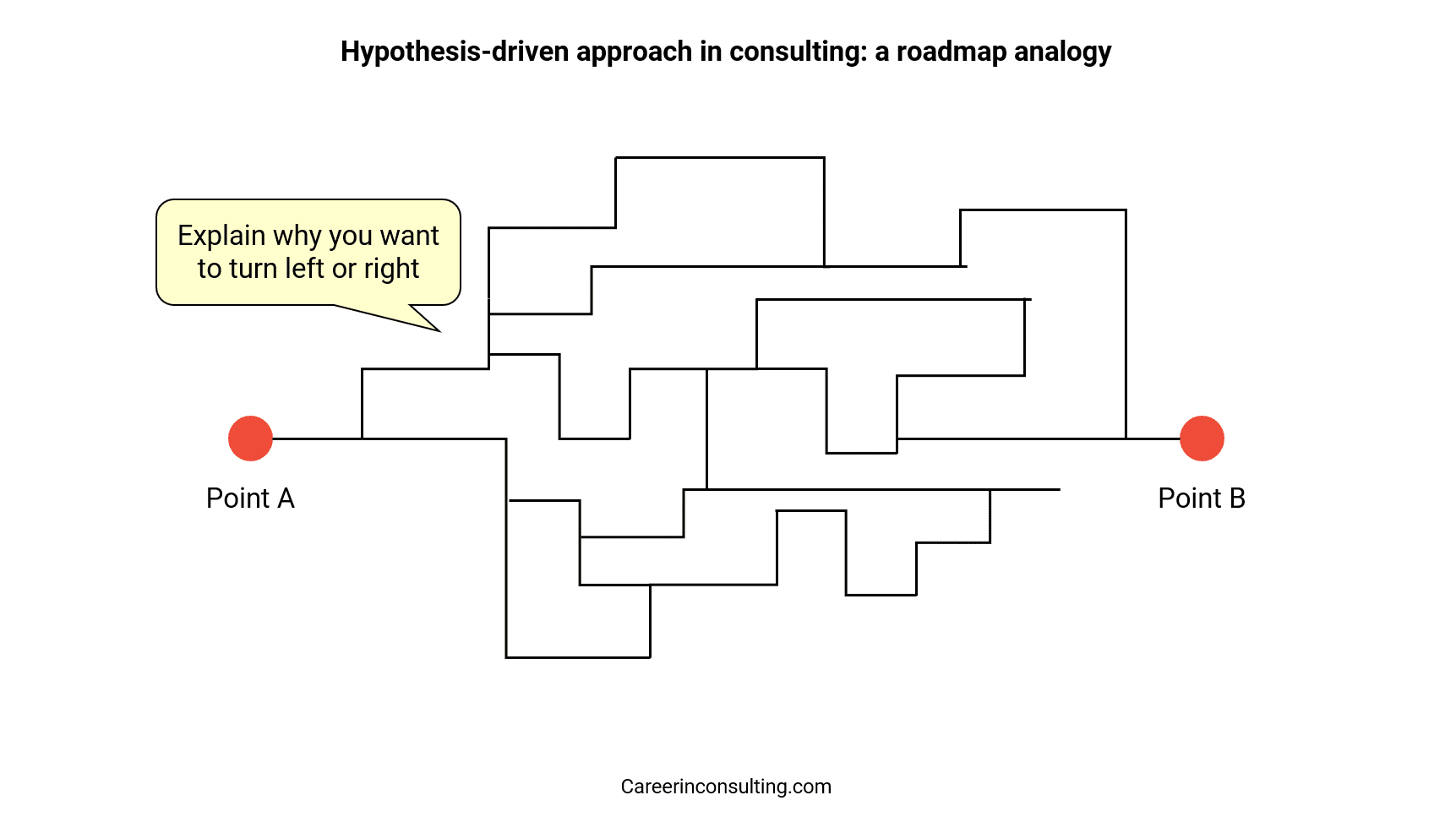

Let’s imagine you want to move from point A to point B.

And for that, you have the choice among a multitude of roads.

Using the answer-first approach presented in the last section, you’d know which road to take to move from A to B (for instance the red line in the drawing below).

Again, this would not demonstrate your capacity to find the “best” road to go from A to B.

(regardless of what “best” means. It can be the fastest or the safest for instance.)

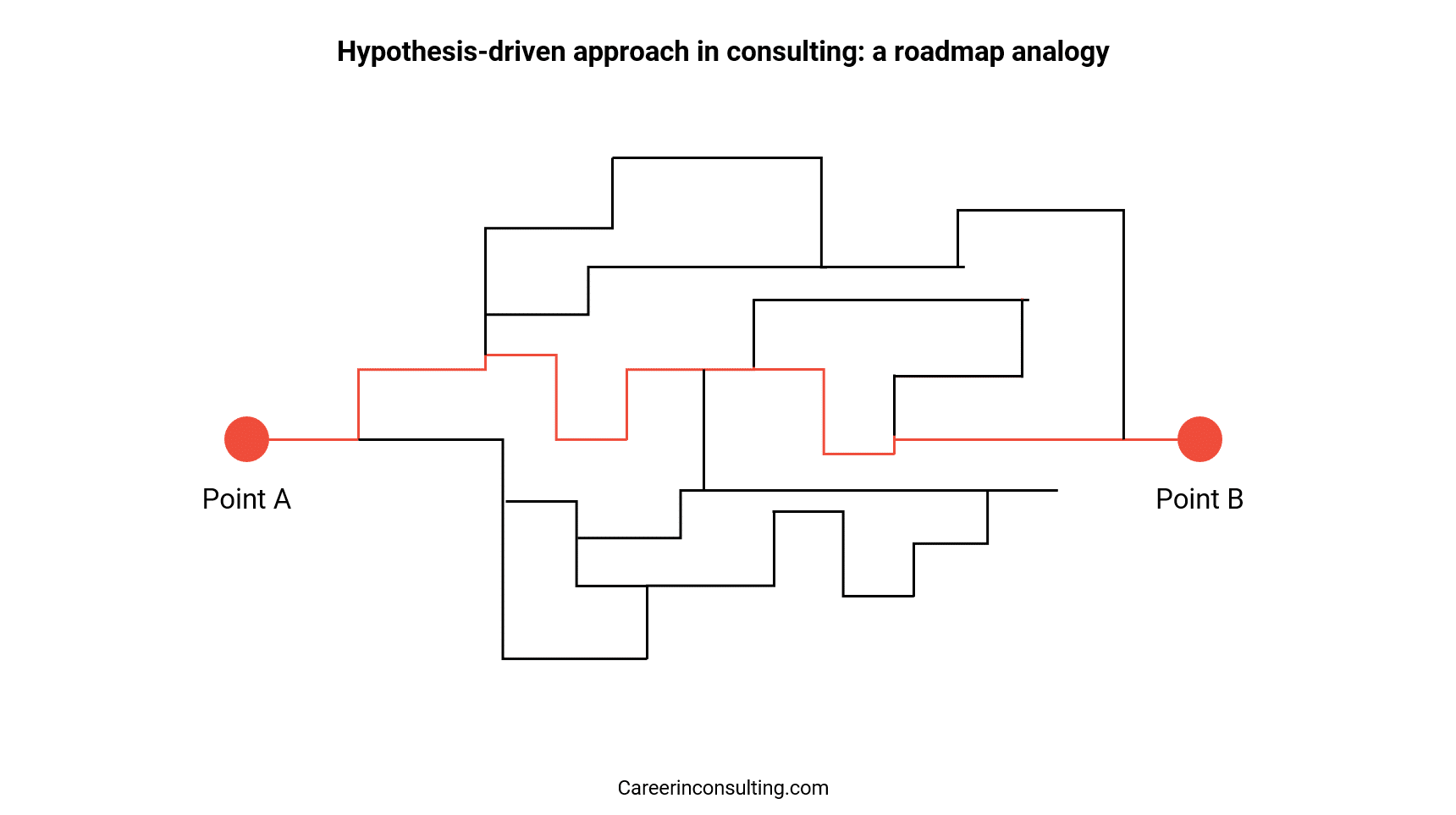

Now, a correct hypothesis-driven approach consists in drawing a map with all the potential routes between A and B, and explaining at each intersection why you want to turn left or right (” my hypothesis is that we should turn right ”).

And in the context of case interviews?

In the above analogy:

- A is the problem

- B is the solution

- All the potential routes are the issues in your issue tree

And the explanation of why you want to take a certain road instead of another would be your hypothesis.

Is the difference between the wrong and right hypothesis-driven approach clearer?

If not, don’t worry. You’ll find many more examples below in this article.

But, next, let’s address another important question.

Why you must (always) use a hypothesis in your case interviews

You must use a hypothesis in your case interviews for two reasons.

A hypothesis helps you focus on what’s important to solve the case

Using a hypothesis-driven approach is critical to solving a problem efficiently.

In other words:

A hypothesis will limit the number of analysis you need to perform to solve a problem.

Thus, this is a way to apply the 80/20 principle and prioritize the issues (from your MECE issue tree ) you want to investigate.

And this is very important because your time with your interviewer is limited (like is the time with your client on a real project).

Let’s take a simple example of a hypothesis:

The profits of your client have dropped.

And your initial analysis shows increasing costs and stagnating revenues.

So your hypothesis can be:

“I think something happened in our cost structure, causing the profit drop. Next, I’d like to understand better the cost structure of our clients and which cost items have changed recently.”

Here the candidate is rigorously “cutting” half of his/her issue tree (the revenue side) and will focus the case discussion on the cost side.

And this is a good example of a hypothesis in case interviews.

Get 4 Complete Case Interview Courses For Free

You need 4 skills to be successful in all case interviews: Case Structuring, Case Leadership, Case Analytics, and Communication. Join this free training and learn how to ace ANY case questions.

A hypothesis tells your interviewers why you want to do an analysis

There is a road that you NEVER want to take.

On this road, the purpose of the questions asked by a candidate is not clear.

Here are a few examples:

“What’s the market size? growth?”

“Who are the main competitors? what are their market shares?”

“Have customer preferences changed in this market?”

This list of questions might be relevant to solve the problem at stake.

But how these questions help solve the problem is not addressed.

Or in other words, the logical connection between these questions and the problem needs to be included.

So, a better example would be:

“We discovered that our client’s sales have declined for the past three years. I would like to know if this is specific to our client or if the whole market has the same trend. Can you tell me how the market size has changed over the past three years? »

In the above question, the reason why the candidate wants to investigate the market is clear: to narrow down the analysis to an internal root cause or an external root cause.

Yet, I see only a few (great) candidates asking clear and purposeful questions.

You want to be one of these candidates.

How to use a hypothesis-driven approach in your case interviews?

At this stage, you understand the importance of a hypothesis-driven approach in case interviews:

You want to identify the most promising areas to analyze (remember that time is money ).

And there are two (and only two) ways to create a good hypothesis in your case interviews:

- a quantitative way

- a qualitative way

Let’s start with the quantitative way to develop a good hypothesis in your case interviews.

The quantitative approach: use the available data

Let’s use an example to understand this data-driven approach:

Interviewer: your client is manufacturing computers. They have been experiencing increasing costs and want to know how to address this issue.

Candidate: to begin with, I want to know the breakdown of their cost structure. Do you have information about the % breakdown of their costs?

Interviewer: their materials costs count for 30% and their manufacturing costs for 60%. The last 10% are SG&A costs.

Candidate: Given the importance of manufacturing costs, I’d like to analyze this part first. Do we know if manufacturing costs go up?

Interviewer: yes, manufacturing costs have increased by 20% over the past 2 years.

Candidate: interesting. Now, it would be interesting to understand why such an increase happened.

You can notice in this example how the candidate uses data to drive the case discussion and prioritize which analysis to perform.

The candidate made a (correct) hypothesis that the increasing costs were driven by the manufacturing costs (the biggest chunk of the cost structure).

Even if the hypothesis were incorrect, the candidate would have moved closer to the solution by eliminating an issue (manufacturing costs are not causing the overall cost increase).

That said, there is another way to develop a good hypothesis in your case interviews.

The qualitative approach: use your business acumen

Sometimes you don’t have data (yet) to make a good hypothesis.

Thus, you must use your business judgment and develop a hypothesis.

Again, let’s take an example to illustrate this approach.

Interviewer: your client manufactures computers and has been losing market shares to their direct competitors. They hired us to find the root cause of this problem.

Candidate: I think of many reasons explaining the drop in market shares. First, our client manufactures and sells not-competitive products. Secondly, we might price our products too high. Third, we need to use the right distribution channels. For instance, we might sell in brick-and-mortars stores when consumers buy their computers in e-stores like Amazon. Finally, I think of our marketing expenses. There may be too low or not used strategically.

Candidate: I see these products as commodities where consumers use price as the main buying decision criteria. That’s why I’d like to explore how our client prices their products. Do you have information about how our prices compare to competitors’?

Interviewer: this is a valid point. Here is the data you want to analyze.

Note how this candidate explains what she/he wants to analyze first (prices) and why (computers are commodities).

In this case interview, the hypothesis-driven approach looks like this:

This is a commodity industry —> consumers buying behavior is driven by pricing —> our client’s prices are too high.

Again, note how the candidate first listed the potential root causes for this situation and did not use an answer-first approach.

Want to learn more?

In this free training , I explain in detail how to use data or your business acumen to prioritize the issues to analyze and “crack the case.”

Also, you’ll learn what to do if you don’t have data or can’t use your business acumen.

Sign up now for free .

Form a hypothesis in these two critical moments of your case interviews

After you’ve presented your initial structure.

The first moment to form a hypothesis in your case interview?

In the beginning, after you’ve presented your structure.

When you’ve presented your issue tree, mention which issue you want to analyze first.

Also, explain why you want to investigate this first issue.

Make clear how the outcome of the analysis of this issue will help you solve the problem.

After an analysis

The second moment to form a hypothesis in your case interview?

After you’ve derived an insight from data analysis.

This insight has proved (or disproved) your hypothesis.

Either way, after you have developed an insight, you must form a new hypothesis.

This can be the issue you want to analyze next.

Or what a solution to the problem is.

Hypothesis-driven approach in case interviews: a conclusion

Having spent about 10 years coaching candidates through the consulting recruitment process , one commonality of successful candidates is that they truly understand how to be hypothesis-driven and demonstrate efficient problem-solving.

Plus, per my experience in coaching candidates , not being able to use a hypothesis is the second cause of rejection in case interviews (the first being the lack of MECEness ).

This means you can’t afford NOT to master this concept in a case study.

So, sign up now for this free course to learn how to use a hypothesis-driven approach in your case interviews and land your dream consulting job.

More than 7,000 people have already signed up.

Don’t waste one more minute!

See you there.

SHARE THIS POST

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

You need 4 skills to be successful in all case interviews: Case Structuring, Case Leadership, Case Analytics, and Communication. Enroll in our 4 free courses and discover the proven systems +300 candidates used to learn these 4 skills and land offers in consulting.

Brought to you by:

Using Hypothesis-Driven Thinking in Strategy Consulting

By: Jeanne M. Liedtka

This technical note describes the process of hypothesis-driven thinking, using examples from strategy consulting, medicine, and architecture. Associated with the scientific method, hypothesis-driven…

- Length: 9 page(s)

- Publication Date: Mar 20, 2006

- Discipline: Business & Government Relations

- Product #: UV0991-PDF-ENG

What's included:

- Same page, Educator Copy

$4.95 per student

degree granting course

$8.95 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

This technical note describes the process of hypothesis-driven thinking, using examples from strategy consulting, medicine, and architecture. Associated with the scientific method, hypothesis-driven thinking focuses on the creative generation of alternative hypotheses and on their subsequent validation or refutation through the use of data. Hypothesis generation asks the creative question, "What if ...?" Hypothesis testing follows with "If ..., then ..." and brings relevant data to bear on the analysis. Taken together, and repeated over time, this sequence allows us to pose ever-improving hypotheses without forfeiting the ability to explore new ideas.

Mar 20, 2006

Discipline:

Business & Government Relations

Darden School of Business

UV0991-PDF-ENG

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Deep Dive into Hypothesis-based Problem Solving

- Post author By Jason Oh

- Post date June 24, 2023

- No Comments on Deep Dive into Hypothesis-based Problem Solving

The hypothesis-based problem solving (HBPS) approach is a method employed by consultants to develop actionable recommendations for clients using a structured, evidence-based process.

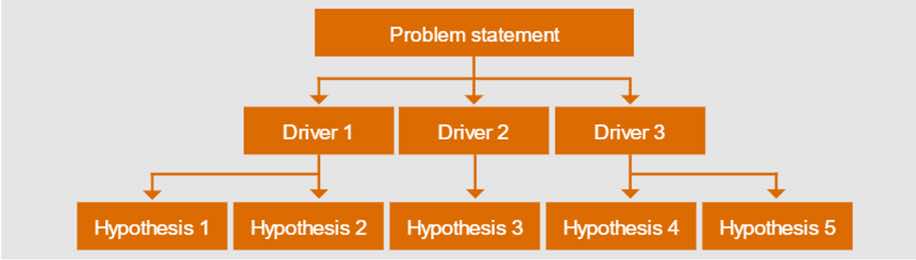

As we saw in the previous article , the HBPS process has five key steps:

- Define the problem

- Define drivers and generate/refine hypotheses

- Determine information needs

- Gather and analyze the data

- Draw conclusions and develop recommendations

In this post, we will explore these five steps in greater detail.

1. Define the problem

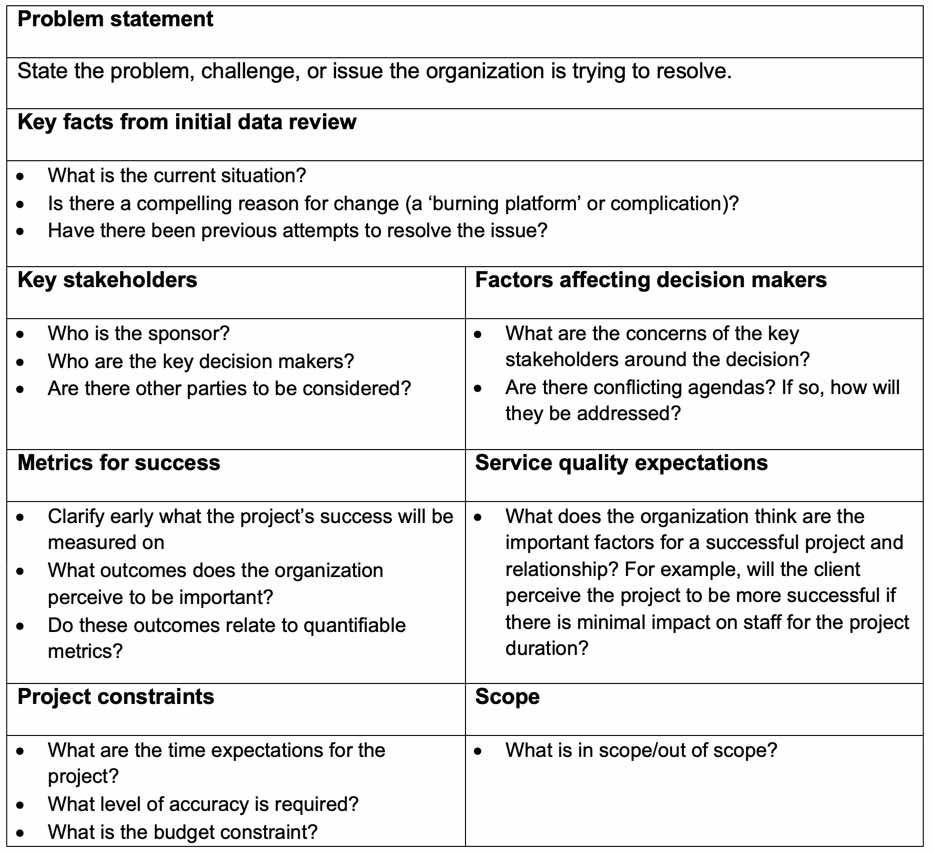

Goal : Create a problem statement.

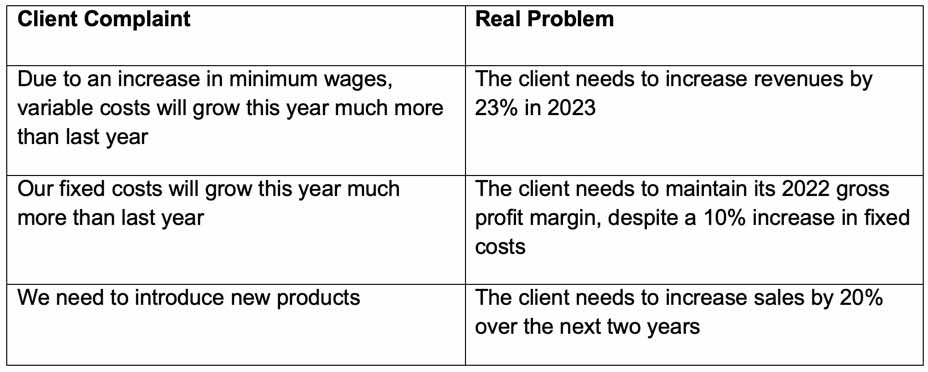

A problem statement is a statement that describes the goals of the client project clearly and concisely. A clear problem statement makes it easier to establish clear boundaries for the project in order to prevent scope creep, ensures that you focus resources and efforts in the right direction, and makes it easier to regularly check back to make sure you are fully addressing the agreed problem. Clients often come to consultants with problems that aren’t well defined. As a result, consultants must make sure that they translate a general complaint into a client problem statement.

A good problem statement should be relevant, action oriented, measurable, and time-bound.

Here are a few examples of what the client might say compared with the real problem.

Notice how each real problem includes a specific target for improvement and a deadline. Without these, you won’t have a clear understanding of the scale of the problem to be solved.

It is worth noting that a problem statement should avoid including symptoms (e.g., Division X productivity is decreasing), methods for solving the problem (e.g., … by benchmarking industry best practices), or proposed solutions (e.g., … by employing more staff).

You must make sure that you agree on the problem statement with the client before proceeding any further. So, to create a robust problem statement you need to involve the client in your thinking to make sure your understanding of the issue aligns with theirs.

Here are some tips that will help you create a robust problem statement:

- Understand who the key stakeholders are and speak to them to understand their views and priorities

- Look at market information and investigate the firm’s previous performance

- Seek to understand the current situation, the compelling reason for change, and previous attempts to resolve the issue

- Understand the factors affecting key decision makers by reviewing concerns and issues and conflicting agendas that may exist

- Ask the client early on ‘What project outcomes would represent success and added value for you?’

- Confirm any project constraints for the client e.g., time, budget

Below is a template that you can use to gather relevant information in order to develop a robust problem statement. You can also download a word version of the template here .

2. Define drivers and generate / refine hypotheses

Goal : Identify the main drivers of the problem and identify possible solutions for each driver.

2.1 Define key drivers

The consultants will need to identify and prioritize the main drivers of the problem by breaking the problem statement down into smaller chunks. Drivers are things that impact the problem you are trying to solve and can be formulated in four different ways:

- Engaging in a group exercise (e.g., mind mapping)

- Adopting different lenses to look at the problem (e.g., a business analysis model such as Porter’s 5 forces / 4 Ps / value chain analysis )

- Brainstorming (i.e., ‘blue sky’ thinking)

- Drawing on past experience (i.e., knowledge of the client’s organization and sector based on previous experience with similar clients)

It’s critical these drivers are kept at a manageable number (around 3 to 5) by clustering them into broader themes. Only include drivers that have high potential value, are worth exploring, and are described in a way that is MECE (i.e., mutually exclusive – don’t overlap each other, and collectively exhaustive – cover all areas relevant to the client).

The drivers need to be broken down into sub-drivers until you can directly define hypothetical answers to the driver question. Identify the relationship between the drivers and order them accordingly. This will help you plan your work, generate hypotheses, and structure your recommendations.

2.2 Generate / refine hypotheses

A hypothesis is a possible solution to a problem that you can test with data and analysis to validate – prove or disprove. Creating good hypotheses is a vital stage in this process, because the wording of the hypotheses will direct the type and amount of data gathering and the analysis that you will subsequently undertake.

In general, a good action-oriented hypothesis should be phrased in the form: “if you do this, you get that”.

To be able to validate a hypothesis, it should have the following five components:

- The expected business impact of the action

- Who it will impact

- How much impact

- After how long

The four golden rules for a hypothesis are that it should be:

Generating hypotheses for possible solutions in a structured way usually involves the following steps:

- Break the problem statement into smaller chunks or drivers

- Cluster the drivers into 3-5 themes

- Make sure the drivers are described in a way that is ‘ MECE ’

- Arrange drivers in a logical sequence

- Develop hypotheses that answer the driver question

- Trim the hypothesis diagram in order to prioritize

After you have a list of the ostensible drivers of the problem, hypothesize solutions for each driver and prioritize them based on impact and ease of implementation.

Lastly, trim the diagram to ensure a manageable workload. That is, remove any low value hypotheses, consider cost and risk. Normally, a 2×2 effort-impact matrix can help you prioritize.

The end result of this process should be a manageable group of high impact hypotheses that you can prove or disprove with data and analysis.

Below is a summary of a good hypothesis diagram:

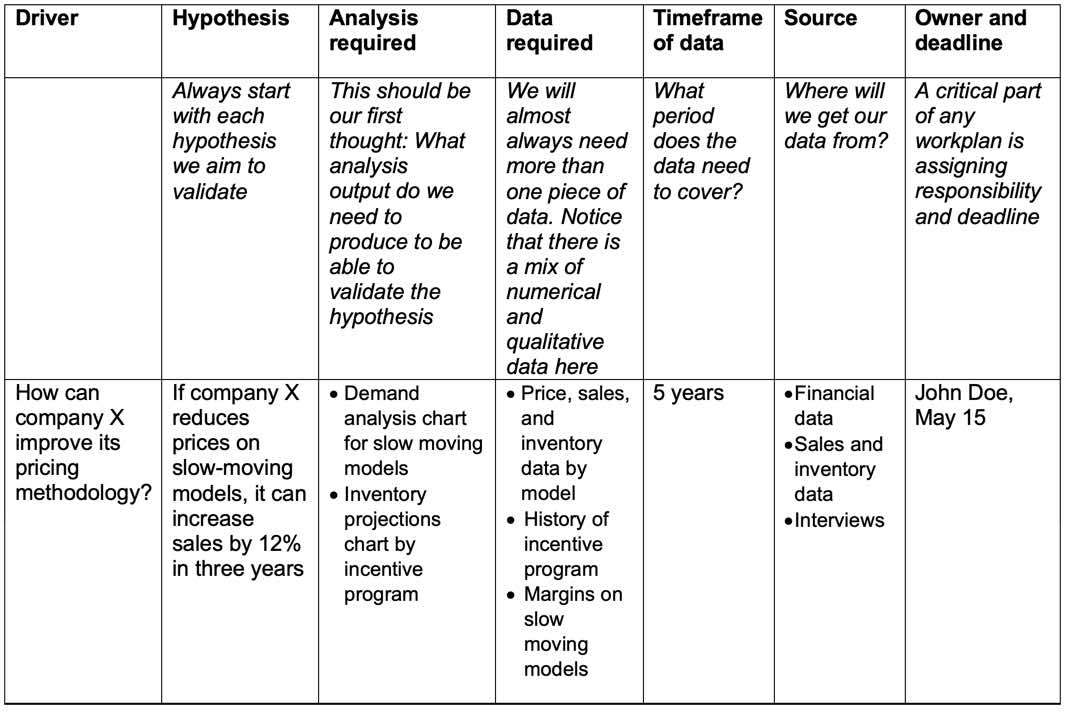

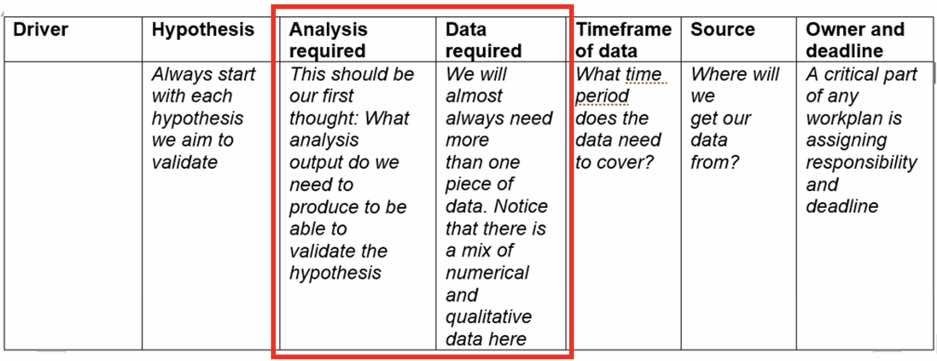

3. Determine information needs

Goal : Build a work plan for the data that you need to collect.

After you have produced a list of testable hypotheses about possible answers to the client problem statement, your next step is to create a workplan. A workplan’s purpose is to help you gather the right amount of data to prove or disprove the hypotheses you have developed.

A workplan has three key benefits:

- Keeps your work closely linked to the problem statement

- Provides a big picture of all your work modules that is easy to share with your team and the client

- Ensures focused and efficient data gathering

To begin with, work out what analysis – or end product – you need to produce in order to validate the hypotheses. This will then allow you to determine what data you will need to gather. Make the workplan details specific and complete, which will help when you start gathering the data. Collaborate with the client to help identify the right types of data for them and how to gather it most efficiently.

Other top tips include:

- Make sure you are gathering just enough data, and no more, to be able to validate the hypothesis

- Prioritize work according to the value to the client, availability of the data, and time to gather and analyze

- Review and revise the workplan as needed, as you gain new insights. Keep looking at the ‘big picture’

- Use the workplan to continue to build up the storyboard for your recommendations

Remember the end product for this step is a piece of analysis that can test the hypotheses.

Traps to avoid:

- Don’t focus exclusively on quantitative data. Qualitative data is just as important, especially to compare with the quantitative data. Aim for the right balance

- Don’t define an ‘analysis required’ in a way that is not sufficient to prove or disprove the hypothesis. For example, if your hypothesis is “Eliminating duplication will save $1M in 12 months”, then your analysis required should not be something vague and generic like “Process analysis”.

- Don’t make the end product an outcome instead of a deliverable. e.g., ‘20% cost savings vs. gap analysis of administration costs’

- Don’t create the workplan just based on data that is easily available. Focus on what you need to be able to validate the hypothesis

Below is a good template, with illustrative inputs, of a well-structured workplan to help you organize and plan the analysis and data required to validate your hypotheses. You can also download a word version of the te mplate here .

4. Gather and analyze data

Goal : Analyze the data, and develop insight from the analysis in order to be able to prove or disprove each hypothesis

In Step 3 of the hypothesis-based problem solving process ‘determine information needs’, you identify the data required to prove or disprove each hypothesis. In Step 4, the aim is to collect the data set out in the workplan and analyze it to produce the required output.

You will need to apply a broad range of skills to collect data effectively, such as:

- Cleaning, manipulating, and simplifying numerical data

- Questioning and listening skills when gathering facts and views from people

- Managing biases about what you want to prove or disprove

Once you have gathered the necessary data, you will then need to perform appropriate data analysis, such as:

- Exploring data sets to identify patterns and relationships

- Comparing qualitative and quantitative data to validate conclusions or identify contradictions

- Modelling different scenarios based on the data

- Determining whether the data proves or disproves the hypothesis

- Determining if the data suggests that the hypothesis needs changing

- Determining if more data is needed

Each part of the analysis should do something useful and be linked to the overall value or benefit delivered to the client. As you analyze the data, keep the following tips in mind:

- Keep revising the hypothesis diagram and workplan. Does your work support the aim of validating the hypothesis?

- Be as ready to disprove a hypothesis as you are to prove it

- If your data proves the hypothesis, you can move on to exploring the course of action

- If your analysis disproves the hypothesis, you’ll need to revisit and restructure it and possibly carry out more analysis

- Keep evolving the storyboard for your recommendations report as you gain new insights

5. Draw conclusions and develop recommendations

Goal : Consolidate your findings to answer the client’s ‘So, what?’ question. Interpret your results to come up with insights and clear recommendations.

You have collected the data and analyzed it. You have probably proved or disproved some hypotheses and identified some interesting facts that weren’t known before. Should you just present the results of the analysis to the client?

Remember, consultants bring value to clients through insights, conclusions, and recommendations. Think commercially about the results of the analysis by asking yourself the ‘So what?’ questions. What does this mean for the organization? What will create the most value for them?

Below are some important things to remember about drawing conclusions and developing recommendations:

- Clients pay for the insights and ideas that consultants provide, not just for data analysis

- Drawing conclusions and developing recommendations requires a mix of drawing logical conclusions from the analysis and creative thinking

- You need to put your analysis together into a powerful and coherent story. You don’t merely want the client to understand the recommendations, you need to excite them to want to take action

- Make sure you get the right people involved. Test your conclusions with subject matter experts or other client stakeholders who can give you an independent view and perhaps spark new ideas. Don’t be afraid of having your conclusions questioned

- As you generate insight, keep going back to the storyboard for your report, update it, sense-check it, and see if your story still has any gaps

- The insights you generate may cause you to go back and review your hypotheses and even the problem statement if you no longer think these are correct. This is part of the iterative nature of HBPS

Typically, you will communicate your recommendations through a report or presentation to the client. How you do this is just as important as the recommendations themselves. You can come up with valuable insights and actionable recommendations for your client, but if you don’t communicate them clearly and effectively, you will not achieve the impact that you are being paid to provide.

Skills that will help you draw conclusions and develop recommendations include:

- Critical thinking skills to challenge your thinking

- Creative thinking skills to come up with more insights

- Looking at the ‘bigger picture’ e.g., How will your recommendations affect other parts of the organization? How realistic are your recommendations?

- Appraising different recommendation options to decide which is of the most value to the client

- Structuring the arguments to support your recommendations

- Powerful writing skills

The bottom line

The hypothesis-based problem solving approach is how a strategy consulting engagement is generally structured and executed. It is an iterative approach. It will usually take several cycles of the HBPS process to arrive at the final answer. Be just as ready to disprove a hypothesis as to prove it. If the hypothesis is disproved, then go back and develop new hypotheses.

Jason Oh is a Senior Associate at Strategy&. Previously, he was part of the Global Wealth & Asset Management Strategy team of a large financial institution and served EY and Novantas in their strategy consulting business with industry focus in the financial services sector.

Image: Pexels

🔴 Interested in consulting?

Get insights on consulting, business, finance, and technology.

Join 5,500 others and subscribe now!

- Tags hypothesis based problem solving

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Issue Tree in Consulting: A Complete Guide (With Examples)

What’s the secret to nailing every case interview ? Is it learning the so-called frameworks? Nuh-uh.

Actually, that secret lies in an under-appreciated, yet extremely powerful problem-solving tool behind every real consulting project . It’s called the “issue tree”, also known as “logic tree” or “hypothesis tree” – and this article will teach you how to master it.

Table of Contents

What is an issue tree?

An issue tree is a pyramidal breakdown of one problem into multiple levels of subsets, called “branches”. It can be presented vertically (top-to-bottom), or horizontally (left-to-right). An issue tree systematically isolates the root causes and ensures impactful solutions to the given problem.

The issue tree is most well-known in management consulting , where consultants use it within the “hypothesis-driven problem-solving approach” - repeatedly hypothesizing the location of the root causes within each branch and testing that hypothesis with data. Once all branches are covered and root causes are found, impactful solutions can be delivered.

The issue tree is only part of the process used in case interviews or consulting projects. As such, it must be learned within the larger context of consulting problem-solving, with six concepts: problem, root cause, issue tree, hypothesis, data & solution , that strictly follow the MECE principle .

Every problem-solving process starts with a well-defined PROBLEM...

A problem is “well-defined” when it is attached with an objective. Let’s get straight to a business problem so you can get a good perspective on how it is done. So here’s one:

Harley-Davidson, a motorcycle company, is suffering from negative profit. Find out why and present a solution.

Now we’ve got our first piece of the tree:

/article/1722501690015_issue_tree_01.png)

...then tries to find its ROOT CAUSES…

To ensure any solution to the problem is long-lasting, consultants always look for the root cause.

Problems are often the last, visible part in a long chain of causes and consequences. Consultants must identify the very start of that chain – the root cause – and promptly deal with it to ensure that the problem is gone for good.

/article/1722501707410_issue_tree_02.png)

The diagram is a simple representation. Real problems can have multiple root causes. That’s where the issue tree comes to the rescue.

Since Harley has been reporting losses, it tried to decrease cost (in the simplest sense, profit = revenue - cost) by shutting down ineffective stores. As you may have imagined, it wasn’t very effective, so Harley set out to find the real source of the problem.

...by breaking it down into different BRANCHES of an issue tree

An issue tree ensures that all root causes are identified in a structured manner by breaking the problem down to different “branches”; each branch is in turn broken down into contributing sub-factors or sub-branches. This process is repeated through many levels until the root causes are isolated and identified.

/article/1722501727553_issue_tree_03.png)

For this problem, Harley deducted that losses must be due to decreasing revenue or increasing cost. Each branch is in turn segmented based on the possible reasons

For a branch to be included in the issue tree, there must be a possibility that it leads to the problem (otherwise, your problem-solving efforts will be wasted on the irrelevant).

To ensure that all possibilities are covered in the issue tree in a neatly organized fashion, consultants use a principle called “ MECE ”. We’ll get into MECE a bit later.

A HYPOTHESIS is made with each branch…

After we’ve developed a few branches for our issue tree, it’s time to hypothesize, or make an educated guess on which branch is the most likely to contain a root cause.

Hypotheses must adhere to 3 criteria:

It must follow the issue tree – you cannot hypothesize on anything outside the tree

It must be top-down – you must always start with the first level of the issue tree

It must be based on existing information – if your information suggests that the root cause is in branch A, you cannot hypothesize that the root cause comes from branch B

Once a hypothesis is confirmed as true (the root cause is inside that branch), move down the branch with a lower-level hypothesis; otherwise, eliminate that branch and move sideways to another one on the same level.

Repeat this process until the whole issue tree is covered and all root causes are identified.

/article/1722501744171_issue_tree_04.png)

Harley hypothesized lower revenue is either due to losing its customers because they came to competitors or they weren’t buying anymore, or it couldn’t attract new buyers

But wait! A little reminder: When solving an issue tree, many make the mistake of skipping levels, ASSUMING that the hypothesis is true instead of CONFIRMING it is.

So, in our example, that means from negative profit, we go straight into “losing old customers” or “can’t attract new customers” before confirming that “decreasing revenue” is true. So if you come back and reconfirm “decreasing revenue” is wrong, your case is completely off, and that’s not something consultants will appreciate, right?

Another common mistake is hopping between sub-branches before confirming or rejecting one branch , so that means you just jump around “losing old customers” and “can’t attract new customers” repeatedly, just to make haste of things. Take things very slowly, step-by-step. You have all the time in the world for your case interview.

But testing multiple sub-branches is possible, so long as they are all under the same branch and have the same assessment criteria.

So for our example, if you are assessing the sales of each motorcycle segment for Harley, you can test all of them at once.

The hypothesis is then tested with DATA...

A hypothesis must always be tested with data.

Data usually yield more insights with benchmarks – reference points for comparison. The two most common benchmarks in consulting are historical (past figures from the same entity) and competitor (figures from similar entities, in the same timeframe).

/article/1722501762432_issue_tree_05.png)

Using “competitor benchmark” to test if competitors are drawing away customers, Harley found that its competitors are also reporting losses, so it must be from something else!

...to find an ACTIONABLE SOLUTION

After the analyzing process, it’s time to deliver actionable solutions. The solutions must attack all the root causes to ensure long-lasting impact – if even one root cause remains untouched, the problem will persist.

Remember to deliver your solutions in a structured fashion, by organizing them in neat and meaningful categories; most of the time, solutions are classified into short-term and long-term.

/article/1722501779448_issue_tree_06.png)

So Harley found that it is losing its traditional customer base - old people, as they were the most vulnerable groups in the pandemic, so they stopped buying motorcycles to save money for essentials, or simply didn’t survive.

Harley also found that it can’t attract new, younger buyers, because of its “old-school” stigma, while also selling at premium price tags. So the short-term solution is setting more attractive prices to get more buyers; and the long-term solution is renewing itself to attract younger audiences.

Our case was a real problem for Harley-Davidson during the pandemic, whose sales plummeted because its target audience were either prioritizing essentials, or dead. So now, Harley has to change itself to attract younger people, or die with its former customer base.

What Is MECE and How Is It Used in an Issue Tree?

A proper issue tree must be MECE, or “ Mutually Exclusive, Collectively Exhaustive .” Mutually exclusive means there’s no overlap between the branches, and collectively exhaustive means all the branches cover every possibility. This is a standard all management consultants swear by, and together with the issue tree, a signature of the industry.

/article/1722501792679_issue_tree_07.png)

To answer whether an issue tree is MECE or not, you need to know all the basic and “advanced” rules of the MECE principle, and we’ll talk about those here. If you want a more comprehensive guide on MECE, check out our dedicated article on MECE .

Basic rule #1: Mutually exclusive

Adherence to this rule ensures that there will be no duplicated efforts, leading to maximum efficiency in problem-solving. It also allows the consultant to isolate the root cause more easily; otherwise, one root cause may manifest in multiple branches, making it harder to pinpoint.

For example, an apparel distributor trying to find out the cause of its decreasing unit sales may use the cleanly-separated product segments: High-end, mid-range, and entry-level. A non-mutually exclusive segmentation here would be: high-end products and footwear.

Basic rule #2: Collectively exhaustive

A collectively exhaustive issue tree also covers only the relevant factors - if one factor is not related to the problem, it must not be included.

If the aforementioned apparel distributor omits any of the product segments in its analysis, it may also ignore one or a few root causes, leading to ineffective problem-solving. But even if it produces runway-exclusive, not-for-sale pieces, those are not included in the issue tree because they don't contribute to unit sales.

Advanced rule #1: Parallel items

This rule requires that all items are on the same logical level.

High-end, mid-range, and entry-level are three parallel and MECE branches. But if we replace the first two with “high-and-mid-range”, the whole issue tree becomes non-parallel and non-MECE, because the new branch is one level higher than the remaining “entry-level” branch.

Advanced rule #2: Orderly List

This rule requires that all items are arranged in a logical order.

So for our apparel distributor, the branches can be arranged as high-mid-low or low-mid-high. Never go “high-low-mid” or “mid-low-high”, because this arrangement is illogical and counter-intuitive.

Advanced rule #3: The “Rule of Three”

The ideal number of branches on any level of the issue tree is three - the most intuitive number to the human mind.

Three items are often enough to yield significant insights, while still being easy to analyze and follow; segmentations into 2 or 4 are also common. 5 is acceptable, but anything more than that should be avoided.

Our apparel distributor may have dozens of product lines across the segments, but having that same number of branches in the issue tree is counter-intuitive and counter-productive, so we use the much more manageable 3 segments.

Advanced rule #4: No Interlinking Items

There should be minimal, and ideally no connections between the branches of the issue tree.

If the branches are interlinked, one root-cause may manifest itself in multiple symptoms across the tree, creating unnecessary confusion in the problem-solving process.

Variants of an issue tree

Beside the “why tree” we used to solve why Harley was reporting losses, there are two other common trees, the “which tree” and the “how tree.” The which tree answers which you should do among the choices, and the how tree answers how you should do something.

Why tree helps locate and attack root causes of a problem

We’ve shown you how a why tree could be used to break down a problem into smaller pieces to find the root causes, which involves several important concepts, but in short there are 3 things you need to do:

Locate root causes by narrowing down your search area. To quickly locate root causes, use breakdown by math, process, steps or segment, or any combination of those. We’ll talk about that a bit later

Identify root causes from what you’ve hypothesized. Remember, all hypotheses must be tested with data before reaching a conclusion

Suggest solutions to attack the root causes to eliminate the problem for good. However, sometimes the root causes cannot be solved effectively and efficiently, so we might also try to mitigate their effects

Which tree helps make the most suitable decision

The which tree is a decision-making table combining two separate issue trees – the available options, and the criteria. The options and criteria included must be relevant to the decision-maker. When considering choosing X over something, consultants might take a look at several factors:

Direct benefits: Does X generate more key output on its own?

Indirect benefits: Does X interact with other processes in a way that generates more key output?

Costs: What are the additional costs that X incur?

Risks: Can we accept the risks of either losing some benefits or increasing cost beyond our control?

Feasibility: Do we have enough resources and capability to do X?

Alternative: Are there any other alternatives that are better-suited to our interests?

Additionally, the issue tree in “Should I Do A or B” cases only contains one level. This allows you to focus on the most suitable options (by filtering out the less relevant), ensuring a top-down, efficient decision-making process.

How tree helps realize an objective

The how tree breaks down possible courses of action to reach an objective. The branches of the tree represent ideas, steps, or aspects of the work. A basic framework for a how tree may look like this:

Identify steps necessary to realize the objective

Identify options for each steps

Choose the best options after evaluations

Again, like the two previous types of issue trees, the ideas/steps/work aspects included must be relevant to the task.

A restaurant business looking to increase its profitability may look into the following ideas:

/article/1722501808940_issue_tree_08.png)

Consulting frameworks – templates for issue trees

Don’t believe in frameworks….

In management consulting, frameworks are convenient templates used to break down and solve business problems (i.e. drawing issue trees).

So you might have heard of some very specific frameworks such as the 4P/7P, or the 3C&P or whatever. But no 2 cases are the same, and the moment you get too reliant on a specific framework is when you realize that you’re stuck.

The truth is, there is no truly “good” framework you can use. Everyone knows how to recite frameworks, so really you aren’t impressing anyone.

The best frameworks are the simplest, easiest to use , but still help you dig out the root causes.

“Simplest, easiest to use” also means you can flexibly combine frameworks to solve any cases, instead of scrambling with the P’s and the C’s, whatever they mean.

“Simplest, easiest to use” frameworks for your case interviews

There are 5 ways you can break down a problem, either through math, segments, steps, opposing sides or stakeholders.

Math : This one is pretty straightforward, you break a problem down using equations and formulae. This breakdown easily ensures MECE and the causes are easily identified, but is shallow, and cannot guarantee the root causes are isolated. An example of this is breaking down profits = revenues - costs

Segments : You break a whole problem down to smaller segments (duh!). For example, one company may break down its US markets into the Northeast, Midwest, South and West regions and start looking at each region to find the problems

Steps : You break a problem down to smaller steps on how to address it. For example, a furniture company finds that customers are reporting faulty products, it may look into the process (or steps) on how its products are made, and find the problems within each steps

Opposing sides : You break a problem down to opposing/parallel sides. An example of this is to break down the solution into short-term and long-term

Stakeholders: You break a problem down into different interacting factors, such as the company itself, customers, competitors, products, etc.

To comprehend the issue tree in greater detail, check out our video and youtube channel :

Scoring in the McKinsey PSG/Digital Assessment

The scoring mechanism in the McKinsey Digital Assessment

Related product

/filters:quality(75)//case_thumb/1669783363736_case_interview_end_to_end_secrets_program.png)

Case Interview End-to-End Secrets Program

Elevate your case interview skills with a well-rounded preparation package

A case interview is where candidates is asked to solve a business problem. They are used by consulting firms to evaluate problem-solving skill & soft skills

Case interview frameworks are methods for addressing and solving business cases. A framework can be extensively customized or off-the-shelf for specific cases.

MECE is a useful problem-solving principle for case interview frameworks with 2 parts: no overlap between pieces & all pieces combined form the original item

Consulting Hypothesis Tree: Everything You Need to Know

- Last Updated May, 2024

A hypothesis tree is a powerful problem-solving framework used by consultants. It takes your hypothesis, your best guess at the solution to your client’s problem, and breaks it down into smaller parts to prove or disprove. With a hypothesis tree, you can focus on what’s important without getting bogged down in details.

Are you feeling overwhelmed during a complex case interview? Try using a hypothesis tree! It’ll help you communicate your insights more effectively, increasing your chances of acing the case.

In this article, we’ll discuss:

- What a hypothesis tree is, and why it’s important in consulting interviews

- Differences between a hypothesis tree vs. an issue tree

- The structure of a hypothesis tree and how to construct one

- A hypothesis tree example

- Our 4 tips for using a hypothesis tree effectively in consulting interviews

Let’s get started!

Definition of a Hypothesis Tree and Why It's Important

6 steps to build a hypothesis tree, hypothesis tree example, 4 tips for using a hypothesis tree in your interview, limitations to using a hypothesis tree, other consulting concepts related to hypothesis trees.

What is Management Consulting vs Strategy Consulting?

How To Decide If You Want To Be a Management or Strategy Consultant

How Top Firms Define Themselves

Top 4 Tips on Figuring Out What Firm is Right For You

A hypothesis tree is a tool consultants use to tackle complex problems by organizing potential insights around a central hypothesis. It provides a structured framework for solving problems by forming sub-hypotheses that, if true, support the central hypothesis. This allows consultants to explore problems more effectively and communicate their insights.

Mastering the hypothesis tree can help you stand out in your case interview. It enables you to showcase your problem-solving skills and critical thinking ability by presenting insights and hypotheses in a concise and organized manner. This helps you avoid getting overwhelmed by the complexity of the client’s problem.

Hypothesis trees are not limited to consulting interviews; they are an essential tool in real-world consulting projects! At the beginning of a project, the partner in charge or the manager will create a hypothesis tree to scope the problem, identify potential solutions, and assign project roles. Acting as a “north star,” a hypothesis tree gives a clear direction for the team, aligning their efforts toward solving the problem. Throughout the project, the team can adapt and refine the hypothesis tree as new information emerges.

The terms “hypothesis tree” and “issue tree” are often used interchangeably in consulting. However, it’s important to understand their key differences.

Differences Between a Hypothesis Tree vs. an Issue Tree

A hypothesis tree is less flexible as it is based on a predetermined hypothesis or set of hypotheses. In contrast, an issue tree can be more flexible in its approach to breaking down a problem and identifying potential solutions.

Let’s look at a client problem and high-level solution frameworks to illustrate the differences: TelCo wants to expand to a new geography. How can we help our client determine their market entry strategy?

If you were to start building a hypothesis tree to explore this, your hypothesis tree might include:

Hypothesis: TelCo should enter the new market.

- It has immense potential and is growing rapidly.

- The expansion is forecasted to be profitable as the costs to operate the service in the new market are low.

- There are few large competitors, and our product has a competitive advantage.

- How attractive is the new market? What is the growth outlook? What is the profitability forecast for this new market?

- What are the different customer segments?

- How is our client’s service differentiated from local competitors?

Nail the case & fit interview with strategies from former MBB Interviewers that have helped 89.6% of our clients pass the case interview.

Here are the 6 steps to build a hypothesis tree. Practice doing these in your mock case interviews!

1. Understand the Problem

Before building a hypothesis tree, you need to understand the problem thoroughly. Gather all the information and data related to the problem. In a case interview, ask clarifying questions after the interviewer has delivered the case problem to help you build a better hypothesis.

2. Brainstorm

Brainstorm and generate as many hypotheses as possible that could solve the problem. Ensure that the hypotheses are MECE. In your interview, you can ask for a few moments to write down your brainstorming before communicating them in a structured way.

3. Organize the Hypotheses

Once you have brainstormed, organize your thoughts into a structured hierarchy. Each hypothesis should be represented as a separate branch in the hierarchy, with supporting hypotheses below.

4. Evaluate the Hypotheses

Evaluate each hypothesis based on its feasibility, relevance, and potential impact on the problem. Eliminate any hypotheses that are unlikely to be valid or don’t provide significant value to the analysis. During your interview, focus on the highest likelihood solutions first. You will not have the time to go through all your hypotheses.

5. Test the Hypotheses

Test your central hypothesis by confirming or refuting each of the sub-hypotheses. If you need data to do this, ask your interviewer for it. Analyze any information you receive and interpret its impact on your hypothesis before moving on. Does it confirm or refute it?

If it refutes your hypothesis, don’t worry. That doesn’t mean you’ve botched your case interview. You just need to pivot to a new hypothesis based on this information.

6. Refine the Hypotheses

Refine the hypothesis tree as you learn more from data or exhibits. You might need to adjust your hypothesis or the structure of the hypothesis tree based on what you learn.

Let’s go back to the TelCo market entry example from earlier.

Hypothesis : TelCo should enter the Indian market and provide internet service.

Market Opportunity : The Indian market is attractive to TelCo.

- The Indian telecommunications market is growing rapidly, and there is room for another provider.

- Margins are higher than in TelCo’s other markets.

- The target customer segments are urban and rural areas with high population densities.

- The competition is low, and there is an opportunity for a new provider for customers who need reliable and affordable service.

Operational Capabilities : The company has the capacity and resources to operate in India.

- TelCo can leverage its existing expertise and technology to gain a competitive advantage.

- TelCo should build out its Indian operations to minimize costs and maximize efficiency.

- TelCo should consider investing in existing local infrastructure to ensure reliable service delivery.

- TelCo can explore alliances with technology content providers to offer value-added services to customers.

Regulatory Environment : The local regulators approve of a new provider entering the market.

- TelCo must ensure compliance with Indian telecommunications regulations.

- TelCo should also be aware of any upcoming regulatory changes that may impact its business operations.

Overall, this hypothesis tree can help guide the analysis and process to conclude if TelCo should enter the Indian market.

1. Develop Common Industry Knowledge

By familiarizing yourself with common industry problems and solutions, you can build a foundation of high-level industry knowledge to help you form relevant hypotheses during your case interviews.

For example, in the mining industry, problems often revolve around declining profitability and extraction quality. Solutions may include reducing waste, optimizing resources, and exploring new sites.

In retail banking, declining customer satisfaction and retention are common problems. Potential solutions are improving customer service, simplifying communication, and optimizing digital solutions.

Consulting club case books like this one from the Fuqua School of Business frequently have industry overviews you can refer to.

2. Practice Building Hypothesis Trees

Building a hypothesis tree requires practice. Look for opportunities to practice generating hypotheses in everyday situations, such as when reading news articles or listening to podcasts. This will help you develop your ability to structure your thoughts and ideas quickly and naturally.

3. Use Frameworks to Guide Building a Hypothesis Tree

Remember, you can reference common business frameworks, such as the profitability formula, as inputs to your hypothesis. Use frameworks as a starting point, but don’t be afraid to deviate from them if it leads to a better hypothesis tree.

Interviewers expect candidates to tailor their approach to the specific client situation. Try to think outside the box and consider new perspectives that may not fit neatly into a framework.

For an overview of common concepts, we have an article on Case Interview Frameworks .

4. Embrace Flexibility

Don’t be afraid to pivot your hypotheses and adjust your approach based on new data or insights. This demonstrates professionalism and openness to feedback, which are highly valued traits in consulting.

Although hypothesis trees are a helpful tool for problem-solving, they have limitations.

The team’s expertise and understanding of the problem are crucial to generating a complete and accurate hypothesis. Relying on a hypothesis tree poses the risk of confirmation bias, as the team may unconsciously favor a solution based on past experiences. This is particularly risky in rapidly evolving industries, such as healthcare technology, where solutions that have worked for past clients may no longer be relevant due to regulatory changes.

A hypothesis tree can also be inflexible in incorporating new information mid-project. It may accidentally limit creativity if teams potentially overlook alternative solutions.

It’s important to be aware of these limitations and use a hypothesis tree with other problem-solving methods.

Several concepts in consulting are related to hypothesis trees. They all provide a structure for problem-solving and analysis. Each has its unique strengths and applications, and consultants may use a combination of these concepts depending on the specific needs of the problem.

Let’s look at some concepts:

- Issue Trees : As mentioned earlier in the article, issue trees are similar to hypothesis trees, but instead of starting with a hypothesis, they start with a problem and break it down into smaller, more manageable issues. Issue trees are often used to identify a problem’s root cause and to prioritize which sub-issues to focus on. If you want to learn more, we have a detailed explanation of Issue Trees .

- MECE Structure : MECE stands for mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive. It is used to organize information and ensure that all possible options are considered. It is often used in conjunction with a hypothesis tree to ensure that all potential hypotheses are considered and that there is no overlap in the analysis. For an overview of the MECE Case Structure , check out our article.

- Pyramid Principle : This is a communication framework for structuring presentations, such as case interviews. It starts with a hypothesis and three to four key arguments, each with supporting evidence. You can use it throughout the case for structuring and communicating ideas, such as at the beginning of a case interview to synthesize your thoughts or when brainstorming ideas in a structured way. To better understand why this tool is valuable, we have a deep dive into The Pyramid Principle .

- Hypothesis-Driven Approach : This is an approach to problem-solving where consultants begin by forming a hypothesis after understanding the client’s problem and high-level range of possibilities. Then, they gather data to test the initial hypothesis. If the data disproves the hypothesis, the consultants repeat the process with the next best hypothesis. To see more examples, read our article on how to apply a Hypothesis-Driven Approach .

– – – – – – –

In this article, we’ve covered:

- Understanding the purpose of a hypothesis tree

- What is different about a hypothesis tree vs. issue tree?

- How to build a hypothesis tree

- 4 tips on how to successfully use a hypothesis tree in your consulting case interview

- Other consulting concepts that are related to hypothesis trees

Still have questions?

If you have more questions about building a hypothesis tree, leave them in the comments below. One of My Consulting Offer’s case coaches will answer them.

Other people interested in the hypothesis tree found the following pages helpful:

- Our Ultimate Guide to Case Interview Prep

- Issue Trees

- Hypothesis-Driven Approach

- MECE Case Structure

Help with Your Consulting Application

Thanks for turning to My Consulting Offer for info on the healthcare case interview. My Consulting Offer has helped 89.6% of the people we’ve worked with to get a job in management consulting. We want you to be successful in your consulting interviews too. For example, here is how Afrah was able to get her offer from Deloitte .

© My CONSULTING Offer

3 Top Strategies to Master the Case Interview in Under a Week

We are sharing our powerful strategies to pass the case interview even if you have no business background, zero casing experience, or only have a week to prepare.

No thanks, I don't want free strategies to get into consulting.

We are excited to invite you to the online event., where should we send you the calendar invite and login information.

McKinsey Problem Solving: Six steps to solve any problem and tell a persuasive story

The McKinsey problem solving process is a series of mindset shifts and structured approaches to thinking about and solving challenging problems. It is a useful approach for anyone working in the knowledge and information economy and needs to communicate ideas to other people.

Over the past several years of creating StrategyU, advising an undergraduates consulting group and running workshops for clients, I have found over and over again that the principles taught on this site and in this guide are a powerful way to improve the type of work and communication you do in a business setting.

When I first set out to teach these skills to the undergraduate consulting group at my alma mater, I was still working at BCG. I was spending my day building compelling presentations, yet was at a loss for how to teach these principles to the students I would talk with at night.

Through many rounds of iteration, I was able to land on a structured process and way of framing some of these principles such that people could immediately apply them to their work.

While the “official” McKinsey problem solving process is seven steps, I have outline my own spin on things – from experience at McKinsey and Boston Consulting Group. Here are six steps that will help you solve problems like a McKinsey Consultant:

Step #1: School is over, stop worrying about “what” to make and worry about the process, or the “how”

When I reflect back on my first role at McKinsey, I realize that my biggest challenge was unlearning everything I had learned over the previous 23 years. Throughout school you are asked to do specific things. For example, you are asked to write a 5 page paper on Benjamin Franklin — double spaced, 12 font and answering two or three specific questions.

In school, to be successful you follow these rules as close as you can. However, in consulting there are no rules on the “what.” Typically the problem you are asked to solve is ambiguous and complex — exactly why they hire you. In consulting, you are taught the rules around the “how” and have to then fill in the what.

The “how” can be taught and this entire site is founded on that belief. Here are some principles to get started:

Step #2: Thinking like a consultant requires a mindset shift

There are two pre-requisites to thinking like a consultant. Without these two traits you will struggle:

- A healthy obsession looking for a “better way” to do things

- Being open minded to shifting ideas and other approaches

In business school, I was sitting in one class when I noticed that all my classmates were doing the same thing — everyone was coming up with reasons why something should should not be done.

As I’ve spent more time working, I’ve realized this is a common phenomenon. The more you learn, the easier it becomes to come up with reasons to support the current state of affairs — likely driven by the status quo bias — an emotional state that favors not changing things. Even the best consultants will experience this emotion, but they are good at identifying it and pushing forward.

Key point : Creating an effective and persuasive consulting like presentation requires a comfort with uncertainty combined with a slightly delusional belief that you can figure anything out.

Step #3: Define the problem and make sure you are not solving a symptom

Before doing the work, time should be spent on defining the actual problem. Too often, people are solutions focused when they think about fixing something. Let’s say a company is struggling with profitability. Someone might define the problem as “we do not have enough growth.” This is jumping ahead to solutions — the goal may be to drive more growth, but this is not the actual issue. It is a symptom of a deeper problem.

Consider the following information:

- Costs have remained relatively constant and are actually below industry average so revenue must be the issue

- Revenue has been increasing, but at a slowing rate

- This company sells widgets and have had no slowdown on the number of units it has sold over the last five years

- However, the price per widget is actually below where it was five years ago

- There have been new entrants in the market in the last three years that have been backed by Venture Capital money and are aggressively pricing their products below costs

In a real-life project there will definitely be much more information and a team may take a full week coming up with a problem statement . Given the information above, we may come up with the following problem statement:

Problem Statement : The company is struggling to increase profitability due to decreasing prices driven by new entrants in the market. The company does not have a clear strategy to respond to the price pressure from competitors and lacks an overall product strategy to compete in this market.

Step 4: Dive in, make hypotheses and try to figure out how to “solve” the problem

Now the fun starts!

There are generally two approaches to thinking about information in a structured way and going back and forth between the two modes is what the consulting process is founded on.

First is top-down . This is what you should start with, especially for a newer “consultant.” This involves taking the problem statement and structuring an approach. This means developing multiple hypotheses — key questions you can either prove or disprove.

Given our problem statement, you may develop the following three hypotheses:

- Company X has room to improve its pricing strategy to increase profitability

- Company X can explore new market opportunities unlocked by new entrants

- Company X can explore new business models or operating models due to advances in technology

As you can see, these three statements identify different areas you can research and either prove or disprove. In a consulting team, you may have a “workstream leader” for each statement.