Hawthorne Effect: Definition, How It Works, and How to Avoid It

Ayesh Perera

B.A, MTS, Harvard University

Ayesh Perera, a Harvard graduate, has worked as a researcher in psychology and neuroscience under Dr. Kevin Majeres at Harvard Medical School.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Key Takeaways

- The Hawthorne effect refers to the increase in the performance of individuals who are noticed, watched, and paid attention to by researchers or supervisors.

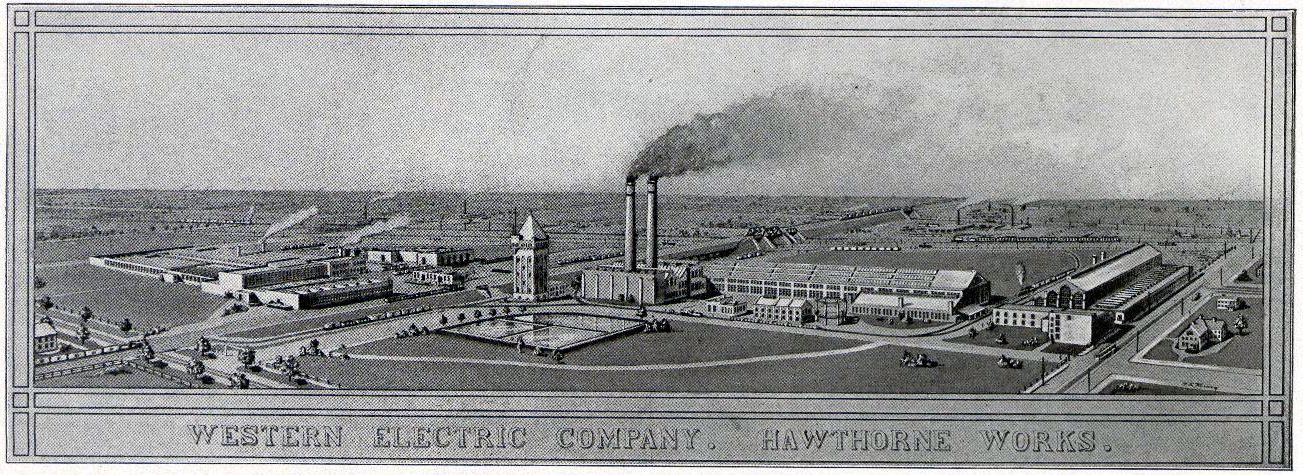

- In 1958, Henry A. Landsberger coined the term ‘Hawthorne effect’ while evaluating a series of studies at a plant near Chicago, Western Electric’s Hawthorne Works.

- The novelty effect, demand characteristics and feedback on performance may explain what is widely perceived as the Hawthorne effect.

- Although the possible implications of the Hawthorne effect remain relevant in many contexts, recent research findings challenge many of the original conclusions concerning the phenomenon.

The Hawthorne effect refers to a tendency in some individuals to alter their behavior in response to their awareness of being observed (Fox et al., 2007).

This phenomenon implies that when people become aware that they are subjects in an experiment, the attention they receive from the experimenters may cause them to change their conduct.

Hawthorne Studies

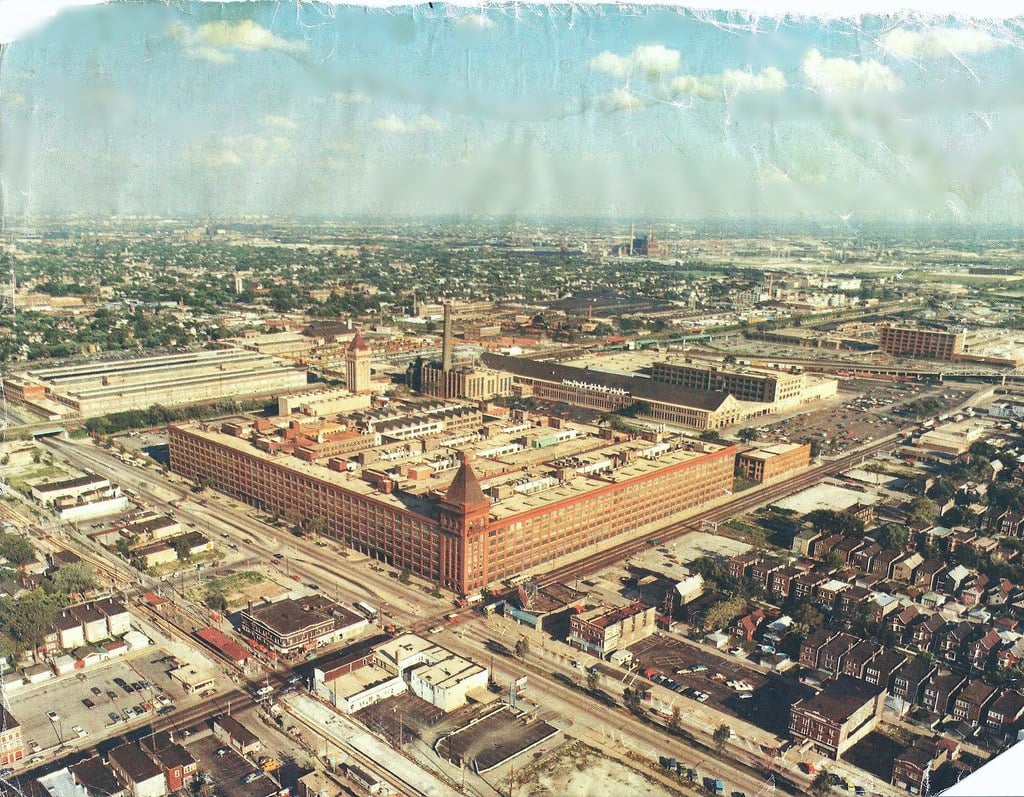

The Hawthorne effect is named after a set of studies conducted at Western Electric’s Hawthorne Plant in Cicero during the 1920s. The Scientists included in this research team were Elton Mayo (Psychologist), Roethlisberger and Whilehead (Sociologists), and William Dickson (company representative).

There are 4 separate experiments in Hawthorne Studies:

Illumination Experiments (1924-1927) Relay Assembly Test Room Experiments (1927-1932) Experiments in Interviewing Workers (1928- 1930) Bank Wiring Room Experiments (1931-1932)

The Hawthorne Experiments, conducted at Western Electric’s Hawthorne plant in the 1920s and 30s, fundamentally influenced management theories.

They highlighted the importance of psychological and social factors in workplace productivity, such as employee attention and group dynamics, leading to a more human-centric approach in management practices.

Illumination Experiment

The first and most influential of these studies is known as the “Illumination Experiment”, conducted between 1924 and 1927 (sponsored by the National Research Council).

The company had sought to ascertain whether there was a relationship between productivity and the work environments (e.g., the level of lighting in a factory).

During the first study, a group of workers who made electrical relays experienced several changes in lighting. Their performance was observed in response to the minutest alterations in illumination.

What the original researchers found was that any change in a variable, such as lighting levels, led to an improvement in productivity. This was true even when the change was negative, such as a return to poor lighting.

However, these gains in productivity disappeared when the attention faded (Roethlisberg & Dickson, 1939). The outcome implied that the increase in productivity was merely the result of a motivational effect on the company’s workers (Cox, 2000).

Their awareness of being observed had apparently led them to increase their output. It seemed that increased attention from supervisors could improve job performance.

Hawthorne Experiment by Elton Mayo

Relay assembly test room experiment.

Spurred by these initial findings, a series of experiments were conducted at the plant over the next eight years. From 1928 to 1932, Elton Mayo (1880–1949) and his colleagues began a series of studies examining changes in work structure (e.g., changes in rest periods, length of the working day, and other physical conditions.) in a group of five women.

The results of the Elton Mayo studies reinforced the initial findings of the illumination experiment. Freedman (1981, p. 49) summarizes the results of the next round of experiments as follows:

“Regardless of the conditions, whether there were more or fewer rest periods, longer or shorter workdays…the women worked harder and more efficiently.”

Analysis of the findings by Landsberger (1958) led to the term the Hawthorne effect , which describes the increase in the performance of individuals who are noticed, watched, and paid attention to by researchers or supervisors.

Bank Wiring Observation Room Study

In a separate study conducted between 1927 and 1932, six women working together to assemble telephone relays were observed (Harvard Business School, Historical Collections).

Following the secret measuring of their output for two weeks, the women were moved to a special experiment room. The experiment room, which they would occupy for the rest of the study, had a supervisor who discussed various changes to their work.

The subsequent alterations the women experienced included breaks varied in length and regularity, the provision (and the non-provision) of food, and changes to the length of the workday.

For the most part, changes to these variables (including returns to the original state) were accompanied by an increase in productivity.

The researchers concluded that the women’s awareness of being monitored, as well as the team spirit engendered by the close environment improved their productivity (Mayo, 1945).

Subsequently, a related study was conducted by W. Lloyd Warner and Elton Mayo, anthropologists from Harvard (Henslin, 2008).

They carried out their experiment on 14 men who assembled telephone switching equipment. The men were placed in a room along with a full-time observer who would record all that transpired. The workers were to be paid for their individual productivity.

However, the surprising outcome was a decrease in productivity. The researchers discovered that the men had become suspicious that an increase in productivity would lead the company to lower their base rate or find grounds to fire some of the workers.

Additional observation unveiled the existence of smaller cliques within the main group. Moreover, these cliques seemed to have their own rules for conduct and distinct means to enforce them.

The results of the study seemed to indicate that workers were likely to be influenced more by the social force of their peer groups than the incentives of their superiors.

This outcome was construed not necessarily as challenging the previous findings but as accounting for the potentially stronger social effect of peer groups.

Hawthorne Effect Examples

Managers in the workplace.

The studies discussed above reveal much about the dynamic relationship between productivity and observation.

On the one hand, letting employees know that they are being observed may engender a sense of accountability. Such accountability may, in turn, improve performance.

However, if employees perceive ulterior motives behind the observation, a different set of outcomes may ensue. If, for instance, employees reason that their increased productivity could harm their fellow workers or adversely impact their earnings eventually, they may not be actuated to improve their performance.

This suggests that while observation in the workplace may yield salutary gains, it must still account for other factors such as the camaraderie among the workers, the existent relationship between the management and the employees, and the compensation system.

A study that investigated the impact of awareness of experimentation on pupil performance (based on direct and indirect cues) revealed that the Hawthorne effect is either nonexistent in children between grades 3 and 9, was not evoked by the intended cues, or was not sufficiently strong to alter the results of the experiment (Bauernfeind & Olson, 1973).

However, if the Hawthorne effect were actually present in other educational contexts, such as in the observation of older students or teachers, it would have important implications.

For instance, if teachers were aware that they were being observed and evaluated via camera or an actual person sitting inside the class, it is not difficult to imagine how they might alter their approach.

Likewise, if older students were informed that their classroom participation would be observed, they might have more incentives to pay diligent attention to the lessons.

Alternative Explanations

Despite the possibility of the Hawthorne effect and its seeming impact on performance, alternative accounts cannot be discounted.

The Novelty Effect

The Novelty Effect denotes the tendency of human performance to show improvements in response to novel stimuli in the environment (Clark & Sugrue, 1988). Such improvements result not from any advances in learning or growth, but from a heightened interest in the new stimuli.

Demand Characteristics

Demand characteristics describe the phenomenon in which the subjects of an experiment would draw conclusions concerning the experiment’s objectives, and either subconsciously or consciously alter their behavior as a result (Orne, 2009). The intentions of the participant—which may range from striving to support the experimenter’s implicit agenda to attempting to utterly undermine the credibility of the study—would play a vital role herein.

Feedback on Performance

It is possible for regular evaluations by the experimenters to function as a scoreboard that enhances productivity. The mere fact that the workers are better acquainted with their performance may actuate them to increase their output.

Despite the seeming implications of the Hawthorne effect in a variety of contexts, recent reviews of the initial studies seem to challenge the original conclusions.

For instance, the data from the first experiment were long thought to have been destroyed. Rice (1982) notes that “the original [illumination] research data somehow disappeared.”

Gale (2004, p. 439) states that “these particular experiments were never written up, the original study reports were lost, and the only contemporary account of them derives from a few paragraphs in a trade journal.”

However, Steven Levitt and John List of the University of Chicago were able to uncover and evaluate these data (Levitt & List, 2011). They found that the supposedly notable patterns were entirely fictional despite the possible manifestations of the Hawthorne effect.

They proposed excess responsiveness to variations induced by the experimenter, relative to variations occurring naturally, as an alternative means to test for the Hawthorne effect.

Another study sought to determine whether the Hawthorne effect actually exists, and if so, under what conditions it does, and how large it could be (McCambridge, Witton & Elbourne, 2014).

Following the systemic review of the available evidence on the Harthorne effect, the researchers concluded that while research participation may indeed impact the behaviors being investigated, discovering more about its operation, its magnitude, and its mechanisms require further investigation.

How to Reduce the Hawthorne Effect

The credibility of experiments is essential to advances in any scientific discipline. However, when the results are significantly influenced by the mere fact that the subjects were observed, testing hypotheses becomes exceedingly difficult.

As such, several strategies may be employed to reduce the Hawthorne Effect.

Discarding the Initial Observations :

- Participants in studies often take time to acclimate themselves to their new environments.

- During this period, the alterations in performance may stem more from a temporary discomfort with the new environment than from an actual variable.

- Greater familiarity with the environment over time, however, would decrease the effect of this transition and reveal the raw effects of the variables whose impact the experimenters are observing.

Using Control Groups:

- When the subjects experiencing the intervention and those in the control group are treated in the same manner in an experiment, the Hawthorne effect would likely influence both groups equivalently.

- Under such circumstances, the impact of the intervention can be more readily identified and analyzed.

- Where ethically permissible, the concealment of information and covert data collection can be used to mitigate the Hawthorne effect.

- Observing the subjects without informing them, or conducting experiments covertly, often yield more reliable outcomes. The famous marshmallow experiment at Stanford University, which was conducted initially on 3 to 5-year-old children, is a striking example.

Frequently Asked Questions

What did the researchers, who identified the hawthorne effect, see as evidence that employee performance was influenced by something other than the physical work conditions.

The researchers of the Hawthorne Studies noticed that employee productivity increased not only in improved conditions (like better lighting), but also in unchanged or even worsened conditions.

They concluded that the mere fact of being observed and feeling valued (the so-called “Hawthorne Effect”) significantly impacted workers’ performance, independent from physical work conditions.

What is the Hawthorne effect in simple terms?

The Hawthorne Effect is when people change or improve their behavior because they know they’re being watched.

It’s named after a study at the Hawthorne Works factory, where researchers found that workers became more productive when they realized they were being observed, regardless of the actual working conditions.

Bauernfeind, R. H., & Olson, C. J. (1973). Is the Hawthorne effect in educational experiments a chimera ? The Phi Delta Kappan, 55 (4), 271-273.

Clark, R. E., & Sugrue, B. M. (1988). Research on instructional media 1978-88. In D. Ely (Ed.), Educational Media and Technology Yearbook, 1994. Volume 20. Libraries Unlimited, Inc., PO Box 6633, Englewood, CO 80155-6633.

Cox, E. (2001). Psychology for A-level . Oxford University Press.

Fox, N. S., Brennan, J. S., & Chasen, S. T. (2008). Clinical estimation of fetal weight and the Hawthorne effect. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 141 (2), 111-114.

Gale, E.A.M. (2004). The Hawthorne studies – a fable for our times? Quarterly Journal of Medicine, (7) ,439-449.

Henslin, J. M., Possamai, A. M., Possamai-Inesedy, A. L., Marjoribanks, T., & Elder, K. (2015). Sociology: A down to earth approach . Pearson Higher Education AU.

Landsberger, H. A. (1958). Hawthorne Revisited : Management and the Worker, Its Critics, and Developments in Human Relations in Industry.

Levitt, S. D., & List, J. A. (2011). Was there really a Hawthorne effect at the Hawthorne plant? An analysis of the original illumination experiments. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3 (1), 224-38.

Mayo, E. (1945). The human problems of an industrial civilization . New York: The Macmillan Company.

McCambridge, J., Witton, J., & Elbourne, D. R. (2014). Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: new concepts are needed to study research participation effects. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67 (3), 267-277.

McCarney, R., Warner, J., Iliffe, S., Van Haselen, R., Griffin, M., & Fisher, P. (2007). The Hawthorne Effect: a randomised, controlled trial. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 7 (1), 1-8.

Rice, B. (1982). The Hawthorne defect: Persistence of a flawed theory. Psychology Today, 16 (2), 70-74.

Orne, M. T. (2009). Demand characteristics and the concept of quasi-controls. Artifacts in behavioral research: Robert Rosenthal and Ralph L. Rosnow’s classic books, 110 , 110-137.

Further Information

- Wickström, G., & Bendix, T. (2000). The” Hawthorne effect”—what did the original Hawthorne studies actually show?. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health, 363-367.

- Levitt, S. D., & List, J. A. (2011). Was there really a Hawthorne effect at the Hawthorne plant? An analysis of the original illumination experiments. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3(1), 224-38.

- Oswald, D., Sherratt, F., & Smith, S. (2014). Handling the Hawthorne effect: The challenges surrounding a participant observer. Review of social studies, 1(1), 53-73.

- Bloombaum, M. (1983). The Hawthorne experiments: a critique and reanalysis of the first statistical interpretation by Franke and Kaul. Sociological Perspectives, 26(1), 71-88.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How the Hawthorne Effect Works

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Nick David / Getty Images

- Does It Really Exist?

Other Explanations

- How to Avoid It

The Hawthorne effect is a term referring to the tendency of some people to work harder and perform better when they are participants in an experiment.

The term is often used to suggest that individuals may change their behavior due to the attention they are receiving from researchers rather than because of any manipulation of independent variables .

The Hawthorne effect has been widely discussed in psychology textbooks, particularly those devoted to industrial and organizational psychology . However, research suggests that many of the original claims made about the effect may be overstated.

History of the Hawthorne Effect

The Hawthorne effect was first described in the 1950s by researcher Henry A. Landsberger during his analysis of experiments conducted during the 1920s and 1930s.

Why Is It Called the Hawthorne Effect?

The phenomenon is named after the location where the experiments took place, Western Electric’s Hawthorne Works electric company just outside of Hawthorne, Illinois.

The electric company had commissioned research to determine if there was a relationship between productivity and work environments.

The original purpose of the Hawthorne studies was to examine how different aspects of the work environment, such as lighting, the timing of breaks, and the length of the workday , had on worker productivity.

Increased Productivity

In the most famous of the experiments, the focus of the study was to determine if increasing or decreasing the amount of light that workers received would have an effect on how productive workers were during their shifts. In the original study, employee productivity seemed to increase due to the changes but then decreased once the experiment was over.

What the researchers in the original studies found was that almost any change to the experimental conditions led to increases in productivity. For example, productivity increased when illumination was decreased to the levels of candlelight, when breaks were eliminated entirely, and when the workday was lengthened.

The researchers concluded that workers were responding to the increased attention from supervisors. This suggested that productivity increased due to attention and not because of changes in the experimental variables.

Findings May Not Be Accurate

Landsberger defined the Hawthorne effect as a short-term improvement in performance caused by observing workers. Researchers and managers quickly latched on to these findings. Later studies suggested, however, that these initial conclusions did not reflect what was really happening.

The term Hawthorne effect remains widely in use to describe increases in productivity due to participation in a study, yet additional studies have often offered little support or have even failed to find the effect at all.

Examples of the Hawthorne Effect

The following are real-life examples of the Hawthorne effect in various settings:

- Healthcare : One study found that patients with dementia who were being treated with Ginkgo biloba showed better cognitive functioning when they received more intensive follow-ups with healthcare professionals. Patients who received minimal follow-up had less favorable outcomes.

- School : Research found that hand washing rates at a primary school increased as much as 23 percent when another person was present with the person washing their hands—in this study, being watched led to improved performance.

- Workplace : When a supervisor is watching an employee work, that employee is likely to be on their "best behavior" and work harder than they would without being watched.

Does the Hawthorne Effect Exist?

Later research into the Hawthorne effect suggested that the original results may have been overstated. In 2009, researchers at the University of Chicago reanalyzed the original data and found that other factors also played a role in productivity and that the effect originally described was weak at best.

Researchers also uncovered the original data from the Hawthorne studies and found that many of the later reported claims about the findings are simply not supported by the data. They did find, however, more subtle displays of a possible Hawthorne effect.

While some additional studies failed to find strong evidence of the Hawthorne effect, a 2014 systematic review published in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology found that research participation effects do exist.

After looking at the results of 19 different studies, the researchers concluded that these effects clearly happen, but more research needs to be done in order to determine how they work, the impact they have, and why they occur.

While the Hawthorne effect may have an influence on participant behavior in experiments, there may also be other factors that play a part in these changes. Some factors that may influence improvements in productivity include:

- Demand characteristics : In experiments, researchers sometimes display subtle clues that let participants know what they are hoping to find. As a result, subjects will alter their behavior to help confirm the experimenter’s hypothesis .

- Novelty effects : The novelty of having experimenters observing behavior might also play a role. This can lead to an initial increase in performance and productivity that may eventually level off as the experiment continues.

- Performance feedback : In situations involving worker productivity, increased attention from experimenters also resulted in increased performance feedback. This increased feedback might actually lead to an improvement in productivity.

While the Hawthorne effect has often been overstated, the term is still useful as a general explanation for psychological factors that can affect how people behave in an experiment.

How to Reduce the Hawthorne Effect

In order for researchers to trust the results of experiments, it is essential to minimize potential problems and sources of bias like the Hawthorne effect.

So what can researchers do to minimize these effects in their experimental studies?

- Conduct experiments in natural settings : One way to help eliminate or minimize demand characteristics and other potential sources of experimental bias is to utilize naturalistic observation techniques. However, this is simply not always possible.

- Make responses completely anonymous : Another way to combat this form of bias is to make the participants' responses in an experiment completely anonymous or confidential. This way, participants may be less likely to alter their behavior as a result of taking part in an experiment.

- Get familiar with the people in the study : People may not alter their behavior as significantly if they are being watched by someone they are familiar with. For instance, an employee is less likely to work harder if the supervisor watching them is always watching.

Many of the original findings of the Hawthorne studies have since been found to be either overstated or erroneous, but the term has become widely used in psychology, economics, business, and other areas.

More recent findings support the idea that these effects do happen, but how much of an impact they actually have on results remains in question. Today, the term is still often used to refer to changes in behavior that can result from taking part in an experiment.

Schwartz D, Fischhoff B, Krishnamurti T, Sowell F. The Hawthorne effect and energy awareness . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2013;110(38):15242-15246. doi:10.1073/pnas.1301687110

McCambridge J, Witton J, Elbourne DR. Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: New concepts are needed to study research participation effects . J Clin Epidemiol . 2014;67(3):267-277. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.015

Letrud K, Hernes S. Affirmative citation bias in scientific myth debunking: A three-in-one case study . Bornmann L, ed. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(9):e0222213. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0222213

McCarney R, Warner J, Iliffe S, van Haselen R, Griffin M, Fisher P. The Hawthorne effect: a randomised, controlled trial . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2007;7:30. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-30

Pickering AJ, Blum AG, Breiman RF, Ram PK, Davis J. Video surveillance captures student hand hygiene behavior, reactivity to observation, and peer influence in Kenyan primary schools . Gupta V, ed. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e92571. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092571

Understanding Your Users . Elsevier ; 2015. doi:10.1016/c2013-0-13611-2

Levitt S, List, JA. Was there really a Hawthorne effect at the Hawthorne plant? An analysis of the original illumination experiments . 2009. University of Chicago. NBER Working Paper No. w15016,

Levitt, SD & List, JA. Was there really a Hawthorne effect at the Hawthorne plant? An analysis of the original illumination experiments . American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 2011;3:224-238. doi:10.2307/25760252

McCambridge J, de Bruin M, Witton J. The effects of demand characteristics on research participant behaviours in non-laboratory settings: A systematic review . PLoS ONE . 2012;7(6):e39116. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039116

Chwo GSM, Marek MW, Wu WCV. Meta-analysis of MALL research and design . System. 2018;74:62-72. doi:10.1016/j.system.2018.02.009

Gnepp J, Klayman J, Williamson IO, Barlas S. The future of feedback: Motivating performance improvement through future-focused feedback . PLoS One . 2020;15(6):e0234444. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0234444

Hawthorne effect . The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation. doi:10.4135/9781506326139.n300

Murdoch M, Simon AB, Polusny MA, et al. Impact of different privacy conditions and incentives on survey response rate, participant representativeness, and disclosure of sensitive information: a randomized controlled trial . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2014;14:90. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-14-90

Landy FJ , Conte JM. Work in the 21st Century: An Introduction to Industrial and Organizational Psychology . New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2010.

McBride DM. The Process of Research in Psychology . London: Sage Publications; 2013.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- HBS Home HBS Index Contact Us

- A New Vision An Essay by Professors Michel Anteby and Rakesh Khurana

- Introduction

- The Hawthorne Plant

- Employee Welfare

- Illumination Studies and Relay Assembly Test Room

- Enter Elton Mayo

- Human Relations and Harvard Business School

- Women in the Relay Assembly Test Room

- The Interview Process

- Spreading the Word

- Next The "Hawthorne Effect"

The “Hawthorne Effect”

What Mayo urged in broad outline has become part of the orthodoxy of modern management.

In 1966, Roethlisberger and William Dickson published Counseling in an Organization , which revisited lessons gained from the experiments. Roethlisberger described “the Hawthorne effect” as the phenomenon in which subjects in behavioral studies change their performance in response to being observed. Many critics have reexamined the studies from methodological and ideological perspectives; others find the overarching questions and theories of the time have new relevance in light of the current focus on collaborative management. The experiments remain a telling case study of researchers and subsequent scholars who interpret the data through the lens of their own times and particular biases. 12

Mayo and Roethlisberger helped define a new curriculum focus, one in alliance with Dean Donham’s desire to address social and industrial issues through field-based empirical research. Harvard’s role in the Hawthorne experiments gave rise to the modern application of social science to organization life and lay the foundation for the human relations movement and the field of organizational behavior (the study of organizations as social systems) pioneered by George Lombard, Paul Lawrence, and others.

“Instead of treating the workers as an appendage to ‘the machine’,” Jeffrey Sonnenfeld notes in his detailed analysis of the studies, the Hawthorne experiments brought to light ideas concerning motivational influences, job satisfaction, resistance to change, group norms, worker participation, and effective leadership. 13 These were groundbreaking concepts in the 1930s. From the leadership point of view today, organizations that do not pay sufficient attention to ‘people’ and ‘cultural’ variables are consistently less successful than those that do. From the leadership point of view today, organizations that do not pay sufficient attention to people and the deep sentiments and relationships connecting them are consistently less successful than those that do. “The change which you and your associates are working to effect will not be mechanical but humane.” 14

- Research Links

- Baker Library | Historical Collections | Site Credits | Digital Accessibility

- Contact Email: [email protected]

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: New concepts are needed to study research participation effects ☆

Jim mccambridge, john witton, diana r elbourne.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author. Tel.: +44-20-7927-2945. [email protected]

Accepted 2013 Aug 13.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This study aims to (1) elucidate whether the Hawthorne effect exists, (2) explore under what conditions, and (3) estimate the size of any such effect.

Study Design and Setting

This systematic review summarizes and evaluates the strength of available evidence on the Hawthorne effect. An inclusive definition of any form of research artifact on behavior using this label, and without cointerventions, was adopted.

Nineteen purposively designed studies were included, providing quantitative data on the size of the effect in eight randomized controlled trials, five quasiexperimental studies, and six observational evaluations of reporting on one's behavior by answering questions or being directly observed and being aware of being studied. Although all but one study was undertaken within health sciences, study methods, contexts, and findings were highly heterogeneous. Most studies reported some evidence of an effect, although significant biases are judged likely because of the complexity of the evaluation object.

Consequences of research participation for behaviors being investigated do exist, although little can be securely known about the conditions under which they operate, their mechanisms of effects, or their magnitudes. New concepts are needed to guide empirical studies.

Keywords: Hawthorne effect, Reactivity, Observation, Research methods, Research participation, Assessment

1. Introduction

What is new.

Most of the 19 purposively designed evaluation studies included in this systematic review provide some evidence of research participation effects.

The heterogeneity of these studies means that little can be confidently inferred about the size of these effects, the conditions under which they operate, or their mechanisms.

There is a clear need to rectify the limited development of study of the issues represented by the Hawthorne effect as they indicate potential for profound biases.

As the Hawthorne effect construct has not successfully led to important research advances in this area over a period of 60 years, new concepts are needed to guide empirical studies.

The Hawthorne effect concerns research participation, the consequent awareness of being studied, and possible impact on behavior [1-5] . It is a widely used research term. The original studies that gave rise to the Hawthorne effect were undertaken at Western Electric telephone manufacturing factory at Hawthorne, near Chicago, between 1924 and 1933 [6-8] . Increases in productivity were observed among a selected group of workers who were supervised intensively by managers under the auspices of a research program. The term was first used in an influential methodology textbook in 1953 [9] . A large literature and repeated controversies have evolved over many decades as to the nature of the Hawthorne effect [5,10] . If there is a Hawthorne effect, studies could be biased in ways that we do not understand well, with profound implications for research [11] .

Empirical data on the Hawthorne effect have not previously been evaluated in a systematic review. Early reviews examined a body of literature on studies of school children and found no evidence of a Hawthorne effect as the term had been used in that literature [12-14] . The contemporary relevance of the Hawthorne effect is clearer within health sciences, in which recent years have seen an upsurge in applications of this construct in relation to a range of methodological phenomena (see examples of studies with nonbehavioral outcomes [15-17] ).

There are two main ways in which the construct of the Hawthorne effect has previously been used in the research literature. First, there are studies that purport to explain some aspect of the findings of the original Hawthorne studies. These studies involve secondary quantitative data analyses [1,18-20] or discussions of the Hawthorne effect, which offer interpretations based on other material [4,10,21,22] . The Hawthorne effect has also been widely used without any necessary connection to the original studies and has usually taken on the meaning of alteration in behavior as a consequence of its observation or other study. In contrast to uses of the term in relation to the original Hawthorne studies, methodological versions of the Hawthorne effect have mutated in meaning over time and across disciplines and been the subject of much controversy [1,2,4,23,24] . This diversity means that certain aspects of the putative Hawthorne effect, for example, novelty [25] are emphasized in some studies and are absent in many others.

There is a widespread social psychological explanation of the possible mechanism for the Hawthorne effect as follows. Awareness of being observed or having behavior assessed engenders beliefs about researcher expectations. Conformity and social desirability considerations then lead behavior to change in line with these expectations. Chiesa and Hobbs [5] point out that just as there are different meanings given to the purported Hawthorne effect, there are also many suggested mechanisms producing the effect, some of which are contradictory. In all likelihood, the most common use of the Hawthorne effect term is as a post hoc interpretation of unexpected study findings, particularly where they are disappointing, for example, when there are null findings in trials.

The aims of this systematic review were to elucidate whether the Hawthorne effect exists, explore under what conditions, and estimate the size of any such effect, by summarizing and evaluating the strength of evidence available in all scientific disciplines. Meeting these study aims contributes to an overarching orientation to better understand whether research participation itself influences behavior. This inclusive orientation eschews restrictions on participants, study designs, and precise definitions of the content of Hawthorne effect manipulations.

The Hawthorne effect under investigation is any form of artifact or consequence of research participation on behavior.

Studies were included if they were based on empirical research comprising either primary or secondary data analyses; were published in English language peer-reviewed journals; were purposively designed to determine the presence of, or measure the size of, the Hawthorne effect, as stated in the introduction or methods sections of the article or before the presentation of findings if the report is not organized in this way; and reported quantitative data on the Hawthorne effect on a behavioral outcome either in observational designs comparing measures taken before and after a dedicated research manipulation or between groups in randomized or nonrandomized experimental studies. Behavioral outcomes incorporate direct measures of behavior and also the consequences of specific behaviors. Studies that described their aims in other ways and also referred to the Hawthorne effect as an alternative conceptualization of the object of evaluation were included as were studies that have other primary aims such as the evaluation of an intervention in a trial in which assessment of the Hawthorne effect is clearly stated as a secondary aim of the study, for example, with the incorporation of control groups with and without Hawthorne effect characteristics. Studies were excluded if: unpublished or in grey literature on the grounds that it is not possible to systematically assess these literature in an unbiased manner; discussion articles and commentaries were not considered to constitute empirical research; they referenced or used the term Hawthorne effect incidentally or described it as a design feature or as part of the study context, or invoked it as an explanation for study findings. Studies of the Hawthorne effect that incorporate nonresearch components, including cointerventions such as feedback, hamper evaluation and are also excluded, as were reanalyses of the original Hawthorne factory data set by virtue of nonresearch cointerventions such as managerial changes (see Ref. [8] for a detailed history of the studies).

Studies were primarily identified in electronic databases. In addition, included studies and key excluded references were backward searched for additional references and forward searched to identify reports that cited these articles. Experts identified in included studies and elsewhere were contacted. The most recent database searches took place on January 3, 2012 for the following databases: Web of Science (1970-), MEDLINE (1950-), BIOSIS Previews (1969-), PsycInfo (1806-), CINAHL Plus with full text (1937-), ERIC (1966-), PubMed (1950-), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (1947-), Embase (1947-), Sociological Abstracts (1952-), National Criminal Justice Reference Service Abstracts (NCJRS; 1970-), Social Services Abstracts (1979-), Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts (LLBA; 1973-), the International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (1951-), APPI Journals (1844-), British Nursing Index (1992-), ADOLEC (1980-), Social Policy and Practice (1890-), British Humanities Index (1962-), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstract (1987-), Inspec (1969-), and PsycARTICLES (1988-).

The term "Hawthorne effect" was searched for as a phrase as widely as possible. If the database permitted, the term was searched for in all fields as was the case for Embase, CINAHL, ERIC, and others. In the Web of Knowledge search, which uses Web of Science, MEDLINE, and BIOSIS Previews databases, "Hawthorne effect" was entered into the "topic" field. The term was also searched for in "keyword" fields for databases such as NCJRS, LLBA, APPI, and others. The use of this term as the core object of evaluation negated the need for a more complex search strategy.

Hits from the database searches were downloaded into EndNote software (Thomson Reuters), removing duplicates there. Screening of titles and abstracts was undertaken by the second author or a research assistant. After a further brief screen of full-text articles, potential inclusions were independently assessed before being included. Data extracted are summarized in the tables presented here, which also contain information on risk of bias in individual studies. Binary outcomes were meta-analyzed in Stata, version 12 (Statacorp), with outcomes pooled in random-effects models using the method by DerSimonian and Laird. The Q and I 2 statistics [26] were used to evaluate the extent and effects of heterogeneity, and outcomes are stratified by study design. Formal methods were not used to assess risk of bias within and across studies, and narrative consideration is given to both. We did not publish a protocol for this review.

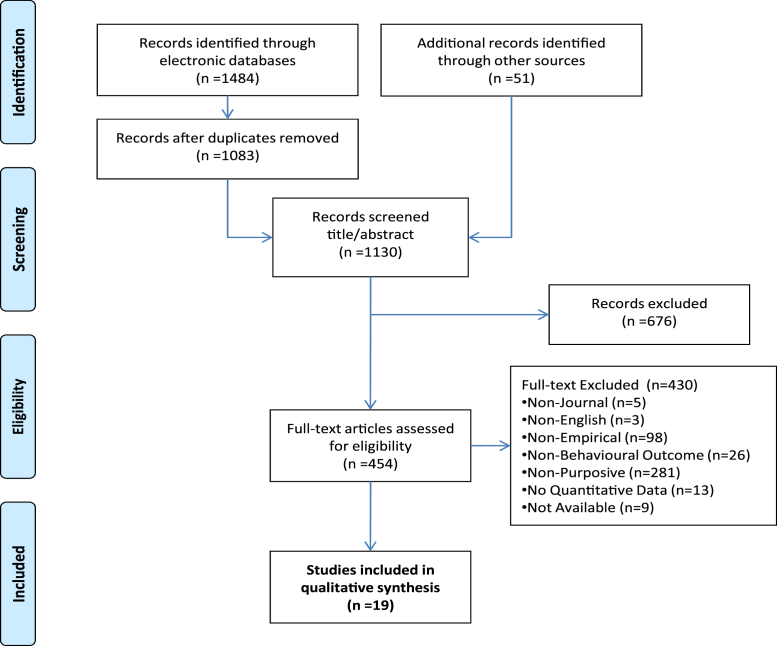

Nineteen studies were eligible for inclusion in this review [27-45] . The PRISMA flowchart summarizing the data collection process is presented in Fig. 1 . The design characteristics of included studies, along with brief summaries of outcome data and observations on most likely sources of bias, are presented separately for randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasiexperimental studies, and observational studies in Tables 1-3 , respectively. All included studies apart from one [27] have been undertaken within health sciences. All observational studies were studies of the Hawthorne effect on health-care practitioners, as were two of the quasiexperimental studies [37,39] . Although none of the randomized trials evaluate possible effects on health-care practitioners, the study by Van Rooyen et al. [28] was undertaken with health researchers. The quasiexperimental studies tend to have been conducted before both the RCTs and observational studies, for which the clear majority of both types of studies have been reported within the past decade. The oldest included study was published approximately 25 years ago [35] . Four of the 5 quasiexperimental studies used some form of quasirandomized methods in constructing control groups (except Ref. [36] ). Heterogeneity in operationalization of the Hawthorne effect for dedicated evaluations, in study populations, settings, and in other ways, is readily apparent in Tables 1-3 .

PRISMA flowchart.

Study characteristics and findings of randomized controlled trials evaluating the Hawthorne effect

Abbreviation : HE, Hawthorne effect.

Study characteristics and findings of quasiexperimental evaluations of the Hawthorne effect

Study characteristics and findings of observational study evaluations of the Hawthorne effect

Abbreviations : HE, Hawthorne effect; EFW, estimate of fetal weight; AHR, antiseptic hand rub; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

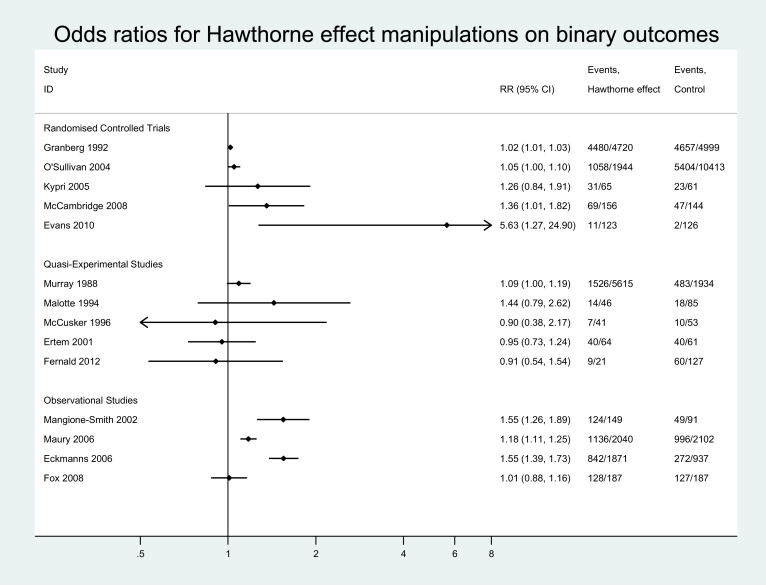

Fourteen of the 19 included studies report evaluations of effects on binary outcome measures. These data are presented in Fig. 2 . The first six studies presented in Fig. 2 comprise six of the seven (not including Ref. [32] ) evaluations of the effects of reporting on one's behavior by answering questions either in interviews or by completing questionnaires. All other studies evaluate being directly observed and/or the awareness of being studied in various ways, apart from one study that combines both types of Hawthorne effect manipulation [33] .

Binary outcome data. RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval.

As a result of heterogeneity in definitions of the Hawthorne effect (reflecting the inclusion criteria), findings from meta-analytic syntheses should be treated with caution. Explorations of the extent and effects of heterogeneity are presented in Table 4 . Pronounced effects of statistical heterogeneity are reflected in the I 2 statistics for two of the three study designs (RCTs and observational studies) and also when attention is restricted to the eight studies of being observed or studied and to the subset of six studies of answering questions, and overall. When the one interview study (of preelection interview effects on voter turnout [27] ) is removed, however, to leave five studies of the effects of self-completing questionnaires on health behaviors, statistical heterogeneity is markedly attenuated.

Extent and effects of heterogeneity in 14 studies of the Hawthorne effect with binary outcomes a

Rows 2-4 are mutually exclusive, as are rows 5 and 6. The final row 7 is a subset of data in row 6.

Bearing these explorations of heterogeneity in mind, effect estimates provide a confidence interval (CI) including unity for the five trials alone [odds ratio (OR), 1.06; 95% CI: 0.98, 1.14], and for the six studies of answering questions (OR, 1.07; 95% CI: 1.00, 1.15). They reach statistical significance in relation to the five studies of self-completing health questionnaires (OR, 1.11; 95% CI: 1.0, 1.23). The pooled estimate for the five quasiexperimental studies is similar to that for the five trials and is not statistically significant (OR, 1.07; 95% CI: 0.99, 1.17), whereas that for the four observational studies (OR, 1.29; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.30) and the eight studies of being observed (OR, 1.21; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.41) are larger and statistically significant. The overall odds ratio, without any weighting for study design, was 1.17 (95% CI: 1.06, 1.30).

Quantitative outcome data were presented in three of the other five studies; two identifying between-group differences [29,32] and one not [28] . The large effect in the study by Feil et al. [29] is noteworthy. In the remaining two studies, continuous measures of effect were not reported in the form of mean differences and were complex to interpret, although both reported statistically significant Hawthorne effect findings [40,43] . Continuous outcomes were also evaluated for two studies included in Fig. 1 , with both finding evidence of statistically significant effects [33,35] .

Of the 19 studies, therefore, 12 provided at least some evidence of the existence of a Hawthorne effect, however this was defined, to a statistically significant degree. Small sample sizes appeared to preclude between-group differences reaching statistical significance in two studies [31,36] . In five studies, it was judged clear that there were no between-group differences that could represent a possible Hawthorne effect [28,37-39,45] .

4. Discussion

The Hawthorne effect has been operationalized for study as the effects of reporting on one's behavior by answering questions, being directly observed, or otherwise made aware of being studied. There is evidence of effects across these studies, and inconsistencies in this evidence. We explore heterogeneity in targets for, and methods of, study as well as in findings. We will begin by examining the evidence base for each of the study designs, before considering the limitations, interpretation, and implications of this study.

The RCTs tend to provide evidence of small statistically significant effects. There are also studies that showed no effects, and two studies that provided evidence of large effects [29,34] . The study by Feil et al. [29] used a strong manipulation, incorporating a placebo effect, which is not usually considered to be a Hawthorne effect component, in addition to research- and trial-specific participation effects. In both this study and the one undertaken by Evans et al. [34] also finding a large effect, small numbers of participants are involved. The diversity in the content of the manipulations in these studies is emphasized. When one considers the RCT data from the five studies contributing to the meta-analysis [27,30,31,33,34] alongside the three studies that did not, two of which produce statistically significant effects on continuous outcomes [29,32] , it seems that overall, there is evidence of between-group differences in the RCTs. These between-group differences cannot, however, be interpreted to provide consistent or coherent evidence of a single effect.

The same could be said of the diversity of the contents of the manipulations in the quasiexperimental studies, and the picture is made more complex by greater variability in study design features, particularly in relation to allocation methods. Overall, they produce mixed evidence, with a between-group difference in one study [35] , a noteworthy difference in a small underpowered study [36] , and no evidence of between-group differences in the other three studies [37-39] . It is difficult to draw any conclusion from included studies with quasiexperimental designs.

Although their design precludes strong conclusions because of the likelihood of unknown and uncontrolled biases, the heterogeneity of findings in the observational studies is interesting. Two studies produce identical point estimates of effects [41,42] , whereas the other two estimates are similarly different [44,45] . These data suggest that the size of any effects of health-care practitioners being observed or being aware of being studied probably very much depends on what exactly they are doing. Perhaps, this is not at all surprising, although it does undermine further the idea that there is a single effect, which can be called the Hawthorne effect. Rather, the effect, if it exists, is highly contingent on task and context. It is noteworthy that the three other studies with health professionals, all using control groups, show no effects [28,37,39] .

This is an "apples and oranges" review. This approach was judged appropriate, given the current level of understanding of the phenomena under investigation. This design decision does, however, entail limitations in the forms of important differences between studies, including operationalization of the Hawthorne effect, and exposure to varying forms of bias. The observed effects are short term when a follow-up study is involved, with only the studies by Murray et al. [35] and Kypri et al. [32] demonstrating effects beyond 6 months. Both these studies involved repeated prior assessments, and both provide self-reported outcome data. Self-reported outcomes do not appear obviously more likely than objectively ascertained outcomes to show effects. The forms of blinding used are often tailored to the nature of the study, making performance bias prevention difficult to evaluate across the studies as a whole.

By design, we have excluded studies that defined the object of evaluation to incorporate nonresearch elements as occurred in the original studies at Hawthorne [8] . We may have missed studies that should have been identified, although this is unlikely if use of the Hawthorne effect term was in any way prominent. Studies that have been missed may be more likely to be older and from nonhealth literature. An alternative design for this study might have eschewed this label and sought instead to synthesize findings on studies of research participation and/or awareness of being studied. Although potentially attractive, this course of action would have involved considerable difficulties in identifying relevant material and would risk losing the main focus on the Hawthorne effect. Similarly, we might have also included studies with cognitive and/or emotional outcomes in which effects might be greater [46] , rather than focusing on behavioral outcomes. This possibility may be appropriate for evaluation in the future. Although we have sought to make our explorations of the heterogeneity of included studies as informative as possible, our analyses might be seen as excessive data fishing. These are, however, clearly presented as post hoc analyses after examination of high levels of heterogeneity, and the study by Granberg and Holmberg [27] is distinct from the other four questionnaire studies in a range of ways including the behavior being investigated.

Heterogeneity in operationalization of the Hawthorne effect make the data in this review challenging to interpret, yet it does appear that research participation can and does influence behavior, at least in some circumstances. The content and strength of the Hawthorne effect manipulations vary in these primary studies, and so to do the effects, although it would not be possible to discern any form of dose-response relationship. The manipulation by Evans et al. [34] may appear in some respects weak, for example, being an online questionnaire, and in others as potentially strong, examining decision making in relation to uptake of a cancer test, which was the study outcome. Although weak uses of the Hawthorne effect term in the wider literature mean that it is not very informative for interpreting the data from this study, outcomes may be considered in relation to the prevailing ideas about the core mechanism of the Hawthorne effect that conformity to perceived norms or researcher expectations drives change. Many, but not all, of the studies with positive findings appear broadly consistent with this account, although so too do many of the studies with negative findings and it is not clear why this is so. The study by Murray et al. [35] examined adolescent smoking at a time when the prevalences of both nonsmoking and regular smoking were approximately one-quarter in this sample, so it is unclear what norms or perceptions of researcher expectations many have been. This study exemplifies the literature as a whole in being principally concerned with the possible existence of a Hawthorne effect and not being designed to test the hypothesized mechanism.

There are other possible mechanisms of effect that have also not been evaluated. For example, regardless of perceptions of norms or researcher expectations, the content of the questions asked may themselves stimulate new thinking. In the studies by Evans et al. [34] and O'Sullivan et al. [30] , patients may well not have previously considered what was being enquired about, and this may have been an independent source of change. Concerns about biases being introduced by having research participants complete questionnaires have existed for more than 100 years, before the Hawthorne factory studies took place and approximately 50 years before the Hawthorne effect term was introduced to the literature (see Ref. [47] for an early history of these issues). Given how long the Hawthorne effect construct has been the predominant conceptualization of these phenomena [48] , it appears that this construct is an inadequate vehicle for advancing understanding of these issues. Alternative long-standing conceptualizations of these problems such as demand characteristics within psychology have also yielded disappointingly underdeveloped research literatures [49-51] . This state of affairs points toward an obvious need for further study of whether, when, how, how much, and for whom research participation may impact on behavior or other study outcomes.

Further studies will be assisted by the development of a conceptual framework that elaborates possible mechanisms of effects and thus targets for study. The Hawthorne effect label has probably stuck for so long simply because we have not advanced our understanding of the issues it represents. We suggest that unqualified use of the term should be abandoned. Specification of the research issues being investigated or described is paramount, regardless of whether the Hawthorne label is seen to be useful or to apply or not in any particular research context. Perhaps, use of the label should be restricted to evaluations in which conformity and social desirability considerations are involved, although it is striking how hostile social psychology has been to this construct [2] . So, what can be said about priority targets for further study on the basis of this systematic review and what concepts are available to guide further study?

Decisions to take part in research studies may also be implicated in efforts to address behavior in other ways so that research participation interacts with other forces influencing behavior. It is also possible, if not likely, that these relatively well-studied types of data collection (completing questionnaires and being observed) are part of a series of events that occur for participants in research studies that have potential to shape their behavior, from recruitment onwards. Giving attention to precisely what we invite research participants to do in any given study seems a logical precursor to examination of whether any aspect of taking part may influence them. Phenomenological studies, which ask participants about their experiences, would seem to be useful for developing new concepts. If individual study contexts are indeed important, we should expect to see effects that vary in size and across populations and research contexts, and perhaps also with multiple mechanisms of effects. The underdeveloped nature of these types of research questions means that it may be unwise to articulate advanced conceptual frameworks to guide empirical study. We propose "research participation effects" as a starting point for this type of thinking. Although descriptive, it also invites investigation of other aspects of the research process beyond data collection, which may simply be where research artifacts emanating from both social norms and other sources are most obvious.

We conclude that there is no single Hawthorne effect. Consequences of research participation for behaviors being investigated have been found to exist in most studies included within this review, although little can be securely known about the conditions under which they operate, their mechanisms of effects, or their magnitudes. Further research on this subject should be a priority for the health sciences, in which we might expect change induced by research participation to be in the direction of better health and thus likely to be confounded with the outcomes being studied. It is also important for other domains of research on human behavior to rectify the limited development of understanding of the issues represented by the Hawthorne effect as they suggest the possibility of profound biases.

Acknowledgments

This study was undertaken under the auspices of a Wellcome Trust Research Career Development award in Basic Biomedical Science to the first author (WT086516MA). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors are grateful to Serena Luchenski for research assistance in connection with this study.

Ethics statement: Ethical approval was not required for this study.

Competing interests: No authors have any competing interests.

Authors' contributions: J.M. had the idea for the study, led on study design, data collection, and data analyses, and wrote the first draft of the report. J.W. assisted with data collection and analyses. All three authors participated in discussions about the design of this study, contributed to revisions of the report, and approved the submission of the final report.

This is an open access article under the CC BY license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ ).

- 1. Parsons H. What happened at Hawthorne? Science. 1974;183:922–932. doi: 10.1126/science.183.4128.922. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Sommer R. The Hawthorne dogma. Psychol Bull. 1968;70(6 Pt 1):592–595. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Wickstrom G., Bendix T. The "Hawthorne effect"-what did the original Hawthorne studies actually show? Scand J Work Environ Health. 2000;26(4):363–367. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Gale E. The Hawthorne studies-a fable for our times? QJM. 2004;97:439–449. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hch070. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Chiesa M., Hobbs S. Making sense of social research: how useful is the Hawthorne effect? Eur J Soc Psychol. 2008;38(1):67–74. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Mayo E. MacMillan; New York, NY: 1933. The human problems of an industrial civilization. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Roethlisberger F.J., Dickson W.J. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1939. Management and the worker. [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Gillespie R. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1991. Manufacturing knowledge: a history of the Hawthorne experiments. [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. French J.R.P. Experiments in field settings. In: Festinger L., Katz D., editors. Research methods in the behavioral sciences. Holt, Rinehart & Winston; New York, NY: 1953. [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Bramel D., Friend R. Hawthorne, the myth of the docile worker, and class bias in psychology. Am Psychol. 1981;36(8):867–878. [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Holden J.D. Hawthorne effects and research into professional practice. J Eval Clin Pract. 2001;7:65–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2001.00280.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Adair J.G., Sharpe D., Huynh C.L. Hawthorne control procedures in educational experiments: a reconsideration of their use and effectiveness. Rev Educ Res. 1989;59(2):215–228. [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Cook D.L. Ohio State University; Columbus, OH: 1967. The impact of the Hawthorne effect in experimental designs in educational research. Final report. [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Adair J.G. The Hawthorne effect-a reconsideration of the methodological artifact. J Appl Psychol. 1984;69(2):334–345. [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Bouchet C., Guillemin F., Briancon S. Nonspecific effects in longitudinal studies: impact on quality of life measures. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:15–20. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00540-4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. McCarney R., Warner J., Iliffe S., van Haselen R., Griffin M., Fisher P. The Hawthorne effect: a randomised, controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-30. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. DeAmici D., Klersy C., Ramajoli F., Brustia L., Politi P. Impact of the Hawthorne effect in a longitudinal clinical study: the case of anaesthesia. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21:103–114. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(99)00054-9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Jones S.R.G. Was there a Hawthorne effect? Am J Sociol. 1992;98:451–468. [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Pitcher B.L. The Hawthorne experiments: statistical evidence for a learning hypothesis. Soc Forces. 1981;60(1):133–149. [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Franke R.H., Kaul J.D. The Hawthorne experiments: first statistical interpretation. Am Sociol Rev. 1978;43(5):623–643. [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Carey A. The Hawthorne studies: a radical criticism. Am Sociol Rev. 1967;32(3):403–416. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Hansson M., Wigblad R. Recontextualizing the Hawthorne effect. Scand J Manage. 2006;22(2):120–137. [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Olson R., Hogan L., Santos L. Illuminating the history of psychology: tips for teaching students about the Hawthorne studies. Psychol Learn Teach. 2006;5(2):110–118. [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Kompier M.A.J. The "Hawthorne effect" is a myth, but what keeps the story going? Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(5):402–412. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1036. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Leonard K.L. Is patient satisfaction sensitive to changes in the quality of care? An exploitation of the Hawthorne effect. J Health Econ. 2008;27(2):444–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.07.004. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Higgins J.P.T., Thompson S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Granberg D., Holmberg S. The Hawthorne effect in election studies-the impact of survey participation on voting. Br J Polit Sci. 1992;22(2):240–247. [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. van Rooyen S., Godlee F., Evans S., Smith R., Black N. Effect of blinding and unmasking on the quality of peer review: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280:234–237. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.3.234. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Feil P.H., Grauer J.S., Gadbury-Amyot C.C., Kula K., McCunniff M.D. Intentional use of the Hawthorne effect to improve oral hygiene compliance in orthodontic patients. J Dent Educ. 2002;66(10):1129–1135. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. O'Sullivan I., Orbell S., Rakow T., Parker R. Prospective research in health service settings: health psychology, science and the 'Hawthorne' effect. J Health Psychol. 2004;9(3):355–359. doi: 10.1177/1359105304042345. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Kypri K., McAnally H.M. Randomized controlled trial of a web-based primary care intervention for multiple health risk behaviors. Prev Med. 2005;41:761–766. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.07.010. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Kypri K., Langley J.D., Saunders J.B., Cashell-Smith M.L. Assessment may conceal therapeutic benefit: findings from a randomized controlled trial for hazardous drinking. Addiction. 2007;102(1):62–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01632.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. McCambridge J., Day M. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of completing the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test questionnaire on self-reported hazardous drinking. Addiction. 2008;103(2):241–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02080.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Evans R., Joseph-Williams N., Edwards A., Newcombe R.G., Wright P., Kinnersley P. Supporting informed decision making for prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing on the web: an online randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(3):e27. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1305. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Murray M., Swan A., Kiryluk S., Clarke G. The Hawthorne effect in the measurement of adolescent smoking. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1988;42:304–306. doi: 10.1136/jech.42.3.304. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Malotte C.K., Morisky D.E. Using an unobstrusively monitored comparison study-group in a longitudinal design. Health Educ Res. 1994;9(1):153–159. [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. McCusker J., Karp E., Yaffe M.J., Cole M., Bellavance F. Determining detection of depression in the elderly by primary care physicians: chart review or questionnaire? Prim Care Psychiatry. 1996:217–221. [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Ertem I.O., Votto N., Leventhal J.M. The timing and predictors of the early termination of breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2001;107(3):543–548. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.3.543. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Fernald D.H., Coombs L., DeAlleaume L., West D., Parnes B. An assessment of the Hawthorne effect in practice-based research. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(1):83–86. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.01.110019. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Campbell J.P., Maxey V.A., Watson W.A. Hawthorne effect-implications for prehospital research. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26(5):590–594. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70009-9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Mangione-Smith R., Elliott M.N., McDonald L., McGlynn E.A. An observational study of antibiotic prescribing behavior and the Hawthorne effect. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1603–1623. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.10482. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Eckmanns T., Bessert J., Behnke M., Gastmeier P., Ruden H. Compliance with antiseptic hand rub use in intensive care units: the Hawthorne effect. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27:931–934. doi: 10.1086/507294. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Leonard K., Masatu M.C. Outpatient process quality evaluation and the Hawthorne effect. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(9):2330–2340. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.003. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Maury E., Moussa N., Lakermi C., Barbut F., Offenstadt G. Compliance of health care workers to hand hygiene: awareness of being observed is important. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(12):2088–2089. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0398-9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Fox N.S., Brennan J.S., Chasen S.T. Clinical estimation of fetal weight and the Hawthorne effect. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;141(2):111–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.07.023. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. French D.P., Sutton S. Reactivity of measurement in health psychology: how much of a problem is it? What can be done about it? Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15(Pt 3):453–468. doi: 10.1348/135910710X492341. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Solomon R.L. An extension of control group design. Psychol Bull. 1949;46(2):137–150. doi: 10.1037/h0062958. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. McCambridge J., Kypri K., Elbourne D.R. A surgical safety checklist. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2373–2374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc090417. author reply 2374-5. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. McCambridge J., Butor-Bhavsar K., Witton J., Elbourne D. Can research assessments themselves cause bias in behaviour change trials? A systematic review of evidence from Solomon 4-group studies. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025223. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. McCambridge J., Kypri K. Can simply answering research questions change behaviour? Systematic review and meta analyses of brief alcohol intervention trials. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e23748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023748. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. McCambridge J., de Bruin M., Witton J. The effects of demand characteristics on research participant behaviours in non-laboratory settings: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e39116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039116. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (498.0 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Lorem ipsum test link amet consectetur a

- Career Skills

- Change Management

- Communication Skills

- Decision Making

- Human Resources

- Interpersonal Skills

- Personal Development

- Program Management

- Project Management

- Team Management

- Learning Tracks

- Free Productivity Course

By Denis G.

Mayo’s Motivation Theory | Hawthorn Effect

In this article:

Mayo’s Human Relations Motivation Theory, which contains the Hawthorn Effect, is a theory of motivation in the workplace.

Have you ever tried to get your team motivated in the workplace? You try various tactics to get your team fired up but nothing really seems to work, and everything stays the way it was. It’s frustrating and demoralizing.

So, what should you do to try and motivate your team to be more productive?

Motivation theories can be helpful in giving us research-based tools to help us raise the performance of our team.

Before Elton Mayo, the prevalent motivational theory for workplace productivity was that of Frederick Taylor, Scientific Management. This theory proposed that employees were motivated primarily by pay. Workers were generally thought of as lazy and treated as just another piece of equipment.

Taylor was an engineer and he viewed productivity through this lens. As such, no recognition of the needs of human beings was considered in Scientific Management.

Mayo’s Motivation Theory, containing the Hawthorn Effect, led to the Human Relations School of thought. This highlights the importance of managers taking more interest in their employees. Mayo believed that both social relationships and job content affected job performance.

Who Was Elton Mayo?

Elton Mayo was born in Australia in 1880. Mayo worked from 1926-1949 as a professor of Industrial Research at Harvard University. He is best known for his work based on the Hawthorn Studies, as well as his book, The Human Problems of an Industrialized Civilization.

The Hathorn Studies

Hawthorn was a Western Electric plant-based in Cicero, Illinois. At its peak, the factory employed close to 40,000 people. The Hawthorn Studies were a large group of productivity studies conducted between 1927 and 1933 that collected large data sets.

The very first study that was done concerned workplace lighting. The study sought to understand if changing lighting conditions resulted in increased or decreased productivity.

To run the experiment two groups were created. A control group and a group with improved lighting conditions. What happened when the lighting was improved for one group? Well, productivity improved for that group.

But, here’s the strange thing. Productivity also improved in the control group! When they reduced lighting for one group productivity also increased! Not only that, but each change (increase or decrease) also lead to increased employee satisfaction.

Many other experiments were run as part of the Hawthorn Studies. Their results also contradicted what was expected from Scientific Management.

So, what’s going on?

This is where Mayo comes in. He was the person who was able to make sense of these results which ran contrary to what everyone expected.

He recognized that the worker isn’t a machine and that how they are treated and their environment is important. He recognized that work is a group activity and employees have a need for comradery and recognition. They have a need for a sense of belonging.

In a nutshell, productivity has a psychological element to it.

The Hawthorn Effect

In addition to the social concern for the worker, one of the big things to come out of the Hawthorn Studies was the Hawthorn Effect. This states that changes in behavior happen when you are monitoring or watching employees. The mere presence of someone watching you changes the way you behave. You start to perform better.

This explains why productivity improved in the first experiment when the lighting was improved, and also when it was made worse.

The Hawthorn Study was the first of its kind to recognize that if you treat an employee a certain way, a good way, they might be more productive for the organization.

Mayo’s Theory of Motivation

Based on analyzing the data of the Hawthorn Studies, Mayo proposed that employees aren’t that motivated by pay and environmental factors. Instead, positive relational factors play a bigger role in productivity.

The importance of group working cannot be overstressed. It is the group that determines productivity, not pay and not processes.

For example, if someone is working too fast they will be ostracised from the group. Likewise, if someone is working too slow the same thing will happen.

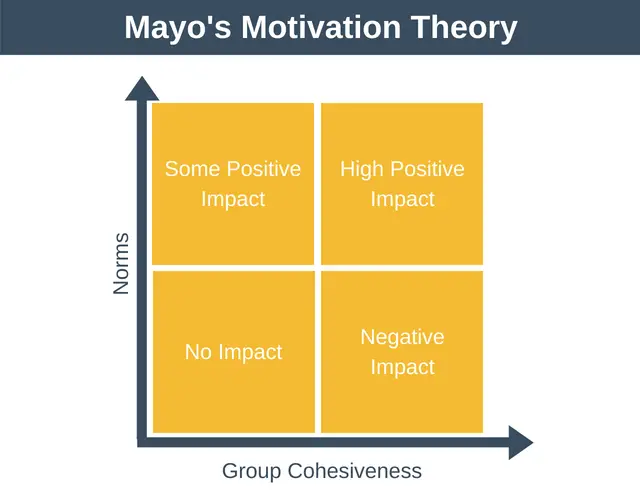

Mayo created this matrix to show how productivity changed in different situations.

You can think of group cohesiveness as being how well the group gets on, their comradery. You can think of norms as being whether the group encourages positive or negative behaviors.

There are four positions in the matrix:

1. Groups with low cohesiveness and low norms

These groups are simply ineffective in terms of productivity. A team like this wouldn’t last very long. This is because nobody would be motivated to be productive in any way.

2. Groups with high cohesiveness and low norms

These types of teams have a negative impact on productivity. Here the team gets on great, but negative behaviors are encouraged rather than positive ones. Gangs are often cited as examples of this type of group.

3. Groups with high norms but low cohesiveness

This type of team can have a limited positive impact on productivity. This is because each team member will be working towards their own success rather than that of the team. If one team member does something great, then good for them, but it doesn’t really improve the productivity of the rest of the team.

4. Groups with high norms and high cohesiveness

These are the teams that can make the greatest positive impact on productivity. In this type of team, each team member supports each other to succeed. People are personally committed to their success and also to the team’s success. A strong support network forms within this type of team.

Using the Model

To use the model to boost the productivity of your team, you should do the following:

1. Strong Communication

Communicate regularly with the members of your team. Giving regular feedback is an important part of this.

Why? Because workers in the Hawthorn Studies were consulted and had the opportunity to give feedback. This resulted in improved productivity.

2. Group Working