- Free Resources

- Register for Free

10 Experimental Drawing Processes

For me, this year is going to be all about ‘process’ and this blog post explores 10 experimental drawing processes. What do I mean by that? Rather than concentrating on single media I’m going to think more carefully about creating processes that my students can go through so that they create exciting, experimental work. We can all get into a bit of a rut with our teaching and my rut has been telling students to make sure they worked with pencil, pen, coloured pencil etc, ie single media. It has been more at the development stage of work that they have mixed things up more, but why not introduce this experimentation earlier in the project?

In the UK students aged 15 and above who pursue art at school have to fulfil an assessment objective that includes ‘recording’. This encompasses photography, drawing with all sorts of different media and writing such as annotation. Personally, I get students to do lots of recording before they look at an artist so that they have the freedom to work any way they want (as long as it’s appropriate for the theme they are investigating). Other art teachers may do this in different ways. My students would go on to look at an artist, develop their work further inspired by this artist, then create compositions and a final piece(s).

10 Experimental Drawing Processes for the Art Room

It’s during this recording phase that I want to introduce more exciting, experimental drawing processes. Here are some ideas:

1. Stick down areas of collage before drawing. The artwork below shows collage which has then had white and grey paint added to it and then a charcoal drawing with white and yellow highlights added in paint.

[Collage + paint + charcoal drawing + paint highlights]

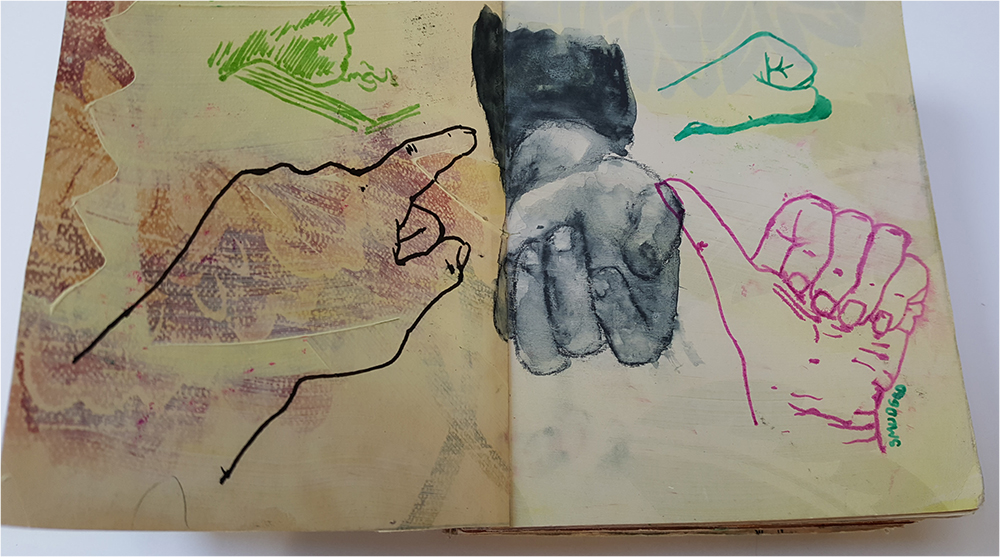

2. Place down appropriate pieces of collage for what you are going to draw. This is different from above as the collage is more part of the drawing rather than a background. Paint loosely with coffee, draw with coloured pencil.

[Draw with collage + loose coffee painting + detailed pencil]

3. Stretch paper, glue on tissue paper with PVA , let it dry, peel off loose bits, sandpaper off rough bits with fine sandpaper, draw with a pen. [Stretch paper + Distressed tissue background + Draw with pen] There is a video by artist Ian Murphy which shows this process here .

4. Stick together two pieces of packaging. Use gumstrip and masking tape to stick on the front like collage and then draw.

[Packageing + gumstrip + masking tape + drawing]

5. Ink splat or drip ink on paper, or work wet on wet with ink or watercolour, allow to dry, then draw.

[Ink or watercolour surface + ballpoint pen drawing].

6. Wet watercolour paper or really thick cartridge paper, blot with tissue so damp, draw with Payne’s grey watercolour. I like to give students a tiny blob from tubed watercolour for this task. You can see below how the watercolour bleeds into the damp paper. If the paper is too wet the drawing becomes completely obscured.

[Wet paper + draw with Payne’s grey watercolour and small brush + allow to dry + detail with Payne’s grey watercolour on dry drawing].

You can choose to leave the drawings as above or to paint on more detail like the example below.

The example of a bee below follows the process described above, only white pen has also been added.

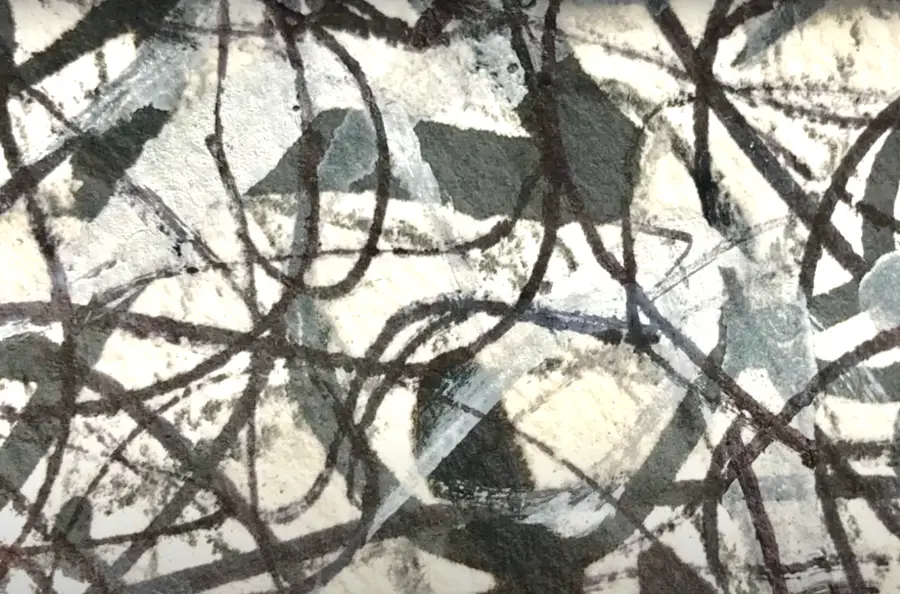

7. Stretch paper, wet paper, dab on strong ink or dilute acrylic, lay down cling film (known as seran wrap in the States) which is deliberately creased, allowed to dry and peel off the clingfilm to reveal a beautiful surface. Draw in coloured pencil, pen or charcoal. The example below used dilute acrylic and charcoal.

[Clingfilm/ink surface + Draw]

8. Print with hessian or old net curtain or doilies, (probably in pale colours) allow to dry, draw on top. (Example coming soon).

9. Create a PowerPoint of images appropriate for the class theme. Give each student pieces of cartridge paper, coloured paper, brown paper, old envelopes et cetera. Give students a variety of media e.g. soft pencil, sharpie, charcoal. Use a timer and put the images on screen and give students three minutes, then two minutes, then one minute to draw the images you display on screen. I had to move the desks in my room to do this. I have done this with students aged 15 and each student drew about 15 drawings in a 50 minute lesson and chose their best 3 to go in their sketchbook. You could ask students to do contour drawings and blind contour drawings.

10. Create a digital line drawing. Create different surfaces (printed, splashed, coffee, collage) print line drawing onto surfaces. Work with different media into prints. E.g. watercolour, Quink ink, stippling.

The example below shows three digital line drawings that have been arranged in a composition. They have then been printed onto a collage of book paper and coffee-stained paper.

I have tried all these processes above before but I just want to make sure I build in more exciting work like this to my planning. It’s part of my desire to be a ‘reflective practitioner’ and continually improve the way I teach.

Of course, there is still a place for using single media. Nothing beats a well-executed pencil drawing on a clean white page. My planning this year includes a pencil drawing and stippled drawing in pen for homework. As long as I show my students good examples that highlight my high expectations it should be alright for students to complete these tasks at home.

If you have any experimental drawing processes that you guide students through please comment below as I would love to hear about them.

If you’ve enjoyed this article about ‘10 experimental drawing processes’ why not register on my website by clicking the link below. If you’re an art teacher, you’ll be able to download 3 of my free teaching resources every month too.

Enjoy this article, Drop it a like

Or share it.

The Arty Teacher

Sarah Crowther is The Arty Teacher. She is a high school art teacher in the North West of England. She strives to share her enthusiasm for art by providing art teachers around the globe with high-quality resources and by sharing her expertise through this blog.

2 responses to “10 Experimental Drawing Processes”

I love to create and use hand made, unique drawing tools with my students. They collect a variety of materials such as q-tips, plastic netting, natural sticks, cardboard cut and frayed, and other materials that can be attached on the end of a wood tongue depressor to create a homemade tool for mark making. Using these tools and ink they can create stunning animal, landscape, and/or still life drawings. The experimental process is challenging and exciting! Love your blog!

This sounds like a great mark making lesson. It’s so engaging if they have to find their own tools. Thanks for your comment.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Sign me up for the newsletter!

Blog Categories

- Art Careers 46

- Art Lesson Resources 23

- Arty Students 6

- Inspiration 68

- Pedagogy 41

- Running an Art Department 21

- Techniques & Processes 47

More Resources you might like...

Subscribe & save in any currency! I WANT TO PAY IN Australian Dollars ($) Canadian Dollars ($) Euros (€) Pound Sterling (£) New Zealand Dollar ($) US Dollars ($) South African rand Change Currency

Free subscription, for one teacher, premium subscription, premium plus subscription, for one or more teachers, privacy overview.

Experimental Drawing Techniques For Inspiring Students

One of the most enjoyable and inspiring aspects of my art education was my introduction to experimental drawing. This immediately expanded my understanding of what drawing is and what it can be used for.

So what is experimental drawing? Experimental drawing, as opposed to traditional drawing, can be defined as the study of purely making marks on a surface. It is both a sensory and physical activity, which has recently been widened to include artwork created in various media . Often an artist will make a deliberate decision not to draw with a pencil , using various materials.

How Do You Create Experimental Drawings?

Mark making and making a mark. Any focus on experimental drawing should and can start with mark-making activities.

Create an experimental drawing book . A good idea is to create a small sketchbook filled with various marks, built in the broadest possible range of materials—focusing on the quality of line and mark-making when completing this task.

Experimental Drawing Examples

Employing a wide variety of experimental materials is essential here. Emphasis can be placed on how a mark is created, say speed drawing , blind mark making using a nontraditional medium to draw with.

Try to overcome misconceptions about experimental drawing techniques , as many of these drawings will have a unique childlike quality. At art school, this traditional idea of ‘good’ illustration does not exist. Look at the following techniques:

Blind Drawing

What is a blind drawing? This method aims to stare at the subject as you draw it continuously. Keep your eyes on the subject matter. The quality of a continuous line drawing will display the freedom that a regular hand drawing will lack. Place the media on the page and focus on observing the object as you draw. Don’t be tempted to look down at your picture until after you have completed it. This method is best attempted under timed conditions.

Negative space drawing

If you are drawing a still life or figure, select a medium that is different from what you usually draw with. For example, concentrate on the spaces between the objects or arms and illustrate the areas. Created between the objects and not the objects themselves. This technique can create some visually exciting compositions and is well worth a try if you are looking to expand your repertoire of drawing methods.

Opposite hand drawing

The opposite hand drawing method is a technique practiced in many art schools and is similar to the continuous line in that its purpose is to introduce the student to a new way of drawing. Again, select a drawing medium that you are not used to working with. Begin drawing with your opposite hand, and focus back on the act of observing and drawing what you see. Again, the quality of these drawings will display freedom and loosening of the line that a more controlled traditional pencil drawing does not present.

Drawing from the elbow and shoulder

The focus of this technique is on how you control the pencil. Instead of drawing on a small piece of A4 or A3, think the large-scale expression. Focus on creating large sweeping expressive marks either from the elbow or the shoulder. This will result in an entirely different type of quality being introduced into your work. As an art student, I remember a student who used his whole body while drawing, twisting, and turning as he created large expressive marks for music.

Drawing with your arm extended or with a long stick

Again, this drawing technique can be practiced on the floor or on a larger sheet of paper attached to a wall. The added benefit of drawing on the floor is that it allows the drawer to move around and engaged directly with the work from many different directions, similar to how Jackson Pollock produced his action paintings. Different drawing mediums can be masked to the end of a stick and used as a device to draw.

This technique explores how different drawing methods can produce different marks in response to observing a figure or a still life, for example.

Imaginative drawing

Ask your students to respond visually and interpret a word. Ask them to return to it in a purely imaginative way. You could extend this task by choosing five words from the dictionary, and students will then be free to interpret a response in the form of a preliminary drawing. They are free to write the word and allow their pictures to develop as they want to.

Touch or contour drawing

This drawing method encourages students to explore and develop new ideas. Place a random object in an enclosed sealed bag. As the students initially focus on the touch or feel of the object inside the container. The objective here is not to guess what is inside and then produce a representation of what they think it is.

Students should be encouraged to respond to their senses intuitively and produce an experimental drawing based on their tactile sense of touch.

Drawing to music

This can be a very successful lesson for motivating and encouraging students and developing drawing skills . As a timed activity, it allows the students to visually interpret what they are listening to. Stick to classical and ambient tunes music as this allows the students to work in a calm and relaxed environment under timed conditions.

Experimental media drawing

As I mentioned earlier, a pencil is not the medium of choice when attempting any of these drawing methods. In fact, the more experimental and unusual your choice is the best. One of the themes I have explored as an artist is the link between the artist's drawing and natural materials.

I was particularly interested in the on-site installations by the British sculptor Richard Long who would make pictures deliberately from the materials he could gather on-site. Inspired by the shear impact of Long's work, I decided to create some on-site drawings on location on the coastline. To do this, I utilized found pieces of driftwood to create drawings in the sand and driftwood sculptures.

Another useful technique I have experimented with is drawing with twigs and charcoal . These drawings, similar to Richard Long’s wall installations, resulted uniquely and effectively in producing highly experimental pictures.

Make a conscious decision not to use a pencil. Charcoal and graphite

Another excellent technique for experimental drawing is to cover the whole page with graphite or charcoal, ensuring the entire sheet. You can then use an eraser to draw into the image and create marks. This drawing method is excellent if you want to create new marks and expand your knowledge of drawing techniques .

What is Experimental Mark Making?

The primary reason behind and wanting to understand the process by which marks can be created for their own sake and how the artist can extend their understanding of drawing techniques.

What is mark-making in Art and Design?

What is mark-making in art and design? The phrase mark making in art and design refers to how artists create patterns, lines, and textures with marks when drawing and painting. This can be expanded to include marks that are produced in any material, be it a line in the sand or an ink brush on paper.

Why is mark-making important?

Why is mark-making important? It allows people to develop practical skills in drawing . This is especially important in young children, where art can be developed intensely as a useful skill in conjunction with an expressive and imaginative outlet.

Holding and controlling a pencil when drawing.

Developing a full repertoire of drawing skills is essential if you want to become accomplished at drawing. Consider the varying levels of mark-making, and control that can be achieved when drawing, say from the wrist instead of the shoulder. The complete artists who wish to respond to the world around them through drawing will be able to work and control their drawings and sketches with a full range of techniques .

Create Art With My Favourite Drawing Resources

General Drawing Courses. I like Udemy if you want to develop your knowledge of drawing techniques. Udemy is an excellent choice due to its wide range of creative courses and excellent refund policy. They often have monthly discounts for new customers, which you can check here. Use my link .

Sketching and Collage. Take a look at this sketching resource I have created. Use this link.

Proko. Is one of my favorite teachers who surpasses in the teaching of Anatomy and Figure drawing. Prokos course breaks down the drawing of the human body into easy-to-follow components aiding the beginner to make rapid progress. For this, I really like Proko.

Art Easels . One of my favorite ways to draw is by using a drawing easel, which develops the skill of drawing on a vertical surface. The H frame easel is an excellent vertical way to add variety to the style and type of marks you create when using a drawing board.

To see all of my most up-to-date recommendations, check out this resource I made for you.

Ian Walsh is the creator and author of improvedrawing.com and an Art teacher based in Merseyside in the United Kingdom. He holds a BA in Fine Art and a PGCE in teaching Art and Design. He has been teaching Art for over 24 Years in different parts of the UK. When not teaching Ian spending his time developing this website and creating content for the improvedrawing channel.

Recent Posts

Online Figure Drawing Classes & Courses For Practicing At Home

Figure drawing is a skill you can master at any age. It's about training the eye to observe and interpret the shape of the human body. As an artist, you can see every form of curve and line....

The Ten Best Online Pencil Drawing Classes

Whether you are a professional or an aspiring artist, you already know that you need to practice more to reach your peak potential. Regardless of how advanced you are in your art practice or what...

- https://www.facebook.com/BigOtherMag

- https://twitter.com/BigOtherMag

- https://instagram.com/BigOtherMag

"[B]eauty is a defiance of authority."—William Carlos Williams

What Is Experimental Art?

One typically hears unusual art called three different things, often interchangeably:

- Avant-Garde

- Experimental

But what do these three words mean? Do they mean the same thing? I don’t think so, and in this post I’ll point out some basic differences between them. I’ll also define what I think experimental art essentially is, and how such art operates.

As I’ve argued here and here —and hopefully have been able to demonstrate in both those places and elsewhere—one encounters innovation simply everywhere : high art, low art, experimental art, mainstream commercial art. The Matrix (1999), for instance, was one of the most popular films of the late 1990s in large part because it exposed mainstream audiences to techniques and ideas that they hadn’t seen before. (I first heard about the film from friends who were bursting with excitement over it, talking on and on about how they couldn’t believe what they had just seen.)

Of course, the Wachowskis mostly borrowed/stole/derived those things from other sources:

Jean Baudrillard (who disliked how the Matrix films used his ideas )

Blade Runner (1982)

Heroic Trio (1993) (dubbed—blame the Weinsteins!—but a high-quality copy)

Ghost in the Shell (1995)

A lot of the art we call innovative works this way. As I wrote in this post :

To innovate literally means “to introduce something new.” But it also means to “make changes in anything established.” Which is the historical meaning of the word’s root: “to renew, alter.”

Innovation does not necessarily mean something new. It means doing something unfamiliar , often with old familiar things. The Matrix draws very heavily from Ghost in the Shell , often recreating images in that film:

Indeed, the Wachowskis originally pitched their film as a live-action version of Ghost in the Shell . But the Wachowskis still had to find ways to recreate those images in real space—a problem requiring often unique solutions. As the above video claims, their success was to synthesize the various things they liked—manga, Hong Kong martial arts films, Buddhism, Continental Theory—into something coherent.

Meanwhile, look what happened after The Matrix came out. As its novelty factor wore off, people grew increasingly tired of films that merely imitated it (including, it seems, The Matrix ’s own sequels). Consider Underworld (2003)—just one of dozens of Matrix clones I could have chosen:

This all said, The Matrix is not what we’d call an experimental film. The Harry Potter novels are in their own way rather innovative —and influential—but J.K. Rowling isn’t an experimental author.

So the experimental isn’t tied exclusively to innovation. (Or, rather: innovation is not tied exclusively to the experimental.)

The Avant-Garde

In 1863, Manet submitted the above painting to the Paris Salon for exhibition. It was rejected. Manet then took advantage of the Salon des Refusés, a venue better than no venue at all.

Which didn’t solve his problems. Manet’s work kept getting refused by the official Salon: it was too flat, too contemporary—and too erotic. (In 1867, he even paid for his own solo exhibition—the equivalent of today’s self-publishing.) But over time, he befriended other refusés (in particular, Edgar Degas, who—always the contrarian—was in self-imposed exile from the Salon). They, inspired by Manet’s solo efforts and by the Salon des Refusés, banded together in 1873 as the “Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers” in order to form their own exhibitions. (Members were supposed to denounce the Salon, but Manet kept submitting his work.)

In 1874, they had their first independent exhibition; other, more successful shows, followed. People started calling them “the Impressionists.” (Degas hated the term, insisting that he was actually a realist). By the mid-1880s, Manet and his colleagues were the leading celebrities of the Parisian art world: the avant-garde of painting.

The term “avant-garde” predates the Impressionists; it was first recorded in the 1825 Saint-Simonian essay “L’artiste, le savant et l’industriel” (“The artist, the scientist and the industrialist”), where it has a very different meaning. That essay called upon artists to serve as the advance guard of the utopian socialist revolution :

It is we artists who will serve as your vanguard; the power of the arts is indeed most immediate and the quickest. We possess arms of all kinds: when we want to spread new ideas among men, we inscribe them upon marble or upon a canvas; we popularize them through poetry and through song; we employ by turns the lyre and the flute, the ode and the song, the story and the novel; the dramatic stage is spread out before us, and it is there that we exert a galvanizing and triumphant influence. We address ourselves to man’s imagination and to his sentiments. We therefore ought always to exert the most lively and decisive action.

(Henri de Saint-Simon was a major influence on Karl Marx. Some attribute this tract to him; others to his follower Olinde Rodrigues .)

As Matei Călinescu notes in Five Faces of Modernity (1987):

By the mid-nineteenth century, the metaphor of the avant-garde had been used by social utopists, reformers of various sorts, and radical journalists, but, to my knowledge, had scarcely been used by literary or artistic figures. (108)

Călinescu sees the term starting to shift toward its more modern usage in 1856, in the literary criticism of Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve. But even then the term,

[f]requently used in the political language or radicalism, […] tended to point toward that type of commitment one would have expected from an artist who conceived of his role as consisting mainly in party politics. That was perhaps one of the reasons why Baudelaire, in the early 1860s, disliked and disapproved of both the term and the concept. (109)

By the time of (and partially due to) Manet and his fellow Impressionists, “avant-garde” had come to mean a group of artists whose work is initially rejected by authority, but that eventually comes to be accepted by society. (Visit any local art fair today, and you’ll see the Impressionists’ long-lasting influence.)

But it doesn’t always work that way. Consider serial music, one of the most powerful experimental forms of 20 th century composition. Derived from Arnold Schönberg’s twelve-tone technique (and atonal ideas well before that), serial composition dominated Western academies and conservatories from 1945 until some point in the 1970s (if not longer):

Serial music has numerous advocates (I rather like all of these works), but they tend to be academicians and others who love music theory—it never really caught on with the general populace, or had that much influence on popular music, or the culture at large. (Here’s the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s current season : Beethoven, Shostakovich, Sibelius, Schubert, Bach, …)

Does that mean that serialist music wasn’t experimental? Quite the contrary! But it wasn’t a successful avant-garde (if it was even avant-garde in the first place).

Minimalism was a more proper avant-garde movement. Its early practitioners—La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass—were acting in opposition to the authority of the academy, looking for an alternative to serialism (as well as to the aleatory techniques of John Cage et al). Excluded by music’s ruling class, they embraced different principles of composition (sustained tones, repetition with variation), and brought their work to alternative venues (loft parties, galleries, museums):

The Minimalists eventually achieved mainstream success—partly because, unlike the serialists, they courted mainstream audiences:

Their influence can be heard throughout modern popular music:

…to choose just a few possible examples.

How many self-professed avant-garde movements turned out to have little or even no effect on the rest of the culture? I’m not claiming that such movements were bad, mind you. But “avant-garde” is often a marketing term, inspired by the fantastic success that the Impressionists had a century ago. And sometimes marketing campaigns work…and sometimes they don’t… But the art can still be experimental even if the rest of the culture never “comes around” to adopting its techniques—or even liking it.

The Experimental

So what is experimental art? What defines it? What makes it experimental ?

To answer those question—to propose answers to those question—I’d first like to invoke Roman Jakobson’s notion of the dominant , which I discussed more at length in this post . Jakobson defined the dominant as

the focusing component of a work of art: it rules, determines, and transforms the remaining components. It is the dominant which guarantees the integrity of the structure. (41)

The dominant, in other words, is that artistic element that the artist values over all others: John Cage and his colleagues took chance techniques as their dominant. The Oulipians work under arbitrary and often severe constraints. The Language poets resist narrative pressures by emphasizing parataxis. And so on. All other aspects then bow to the dominant component.

Experimental artists often claim that they are breaking with the past:

The Impressionists favored color over line, worked en plein air , and chose contemporary rather than classical subjects. The Minimalists refused serialist and chance techniques, preferring to look for some other way of working (one that wasn’t simply a return to the tonal harmony of the 19th century).

But historical precedents can be found even in experimental art:

That Manet! What a little copycat he was! Furthermore, as the popular (and possibly apocryphal) story puts it , Manet met Degas while they were both copying the same painting:

(Regardless of whether that story is true, both Manet and Degas were both enthusiastic—and tremendously skilled—copyists.)

Philip Glass was influenced by Ravi Shankar. Steve Reich was influenced by Ghanan drumming and Balinese gamelan music. Terry Riley was influenced by Pandit Pran Nath and La Monte Young. La Monte Young (a truly great oddball) was influenced by the sounds of high tension power lines, and the wind whipping across the plains :

The very first sound that I recall hearing was the sound of the wind blowing through the chinks and all around the log cabin in Idaho where I was born. I have always considered this among my most important early experiences. It was very awesome and beautiful and mysterious. Since I could not see it and did not know what it was, I questioned my mother about it for long hours. During my childhood there were certain sound experiences of constant frequency that have influenced my musical ideas and development: the sounds of insects; the sounds of telephone poles and motors; sounds produced by steam escaping, such as my mother’s tea-kettle and the sounds of whistles and signals from trains; and resonations set off by the natural characteristics of particular geographic areas such as canyons, valleys, lakes, and plains. Actually, the first sustained single tone at a constant pitch, without a beginning or end, that I heard as a child was the sound of telephone poles, the hum of the wires. This was a very important auditory influence upon the sparse sustained style of work of the genre of the Trio for Strings (1958), Composition 1960 #7 (B and F# “To be held for a long time”) and The Four Dreams of China (1962).

Well, even anarchists like Alec Empire enjoy engaging with older materials:

Continuity is everywhere, even in situations of discontinuity. La Monte Young made music based on noise and drones, but he brought those noises and drones inside lofts, as parts of titled and performed musical compositions. And he synthesized those noises and drones with ideas he’d learned from Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and John Cage. (Young was more open to serialist and chance techniques than the other Minimalists, which is part of why his music sounds so different than theirs.)

The experimental artist can want to quit with all previous convention, but he or she still must communicate by means of some convention. As Frank Kermode put it in The Sense of an Ending (1967):

[N]ovelty in the arts is either communication or noise. If it is noise then there is no more to say about it. If it is communication it is inescapably related to something older than itself. (102)

Schism is simply meaningless without reference to some prior condition; the absolutely New is simply unintelligible, even as novelty. (116)

Furthermore, experimental art often draws on the same materials that non-experimental art does. Here’s an example of Donald Barthelme, Batman comic books, Tim Burton, William Castle, German Expressionism, J.D. Salinger, and Mark Twain all drawing inspiration, to some extent or another, from the same Victor Hugo story (sometimes directly, and sometimes through other works that had themselves been inspired).

So much, then, for the experimental dream of art ex nihilo . But what about the notion of art sui generis ? Synthesizing Jakobson and Kermode, here is my current conception of experimental art:

Experimental art is that which takes unfamiliarity as its dominant— even to the point of schism .

The experimental artist wants her artwork to be different from all the other artworks around her. She desires that her results be unusual, unfamiliar to the point of looking peculiar, perplexing. She may be drawing on conventions, she may be working inside one or more traditions. But her conventions and traditions are not dominant ones; they are, perhaps, older ones, or unpopular ones. Or she may be importing ideas and conventions from one medium into another, where they are not well known.

Or it may be that she has noticed an idea—a possibility—that has not been fully developed in other artworks, and therefore seeks to develop it. She exaggerates or expands that minor concept or idea (something that isn’t dominant in other works) until it overwhelms the more familiar aspects of her artwork, distorting and enstranging the entire thing. Hence Manet and Degas exaggerated the de-emphasis of line and more energetic brushstrokes that they observed in works by Velázquez, J. M. W. Turner, and Eugène Delacroix, developing that idea until they arrived at Impressionism.

Luckily for experimental artists, there exist audiences and critics who prize unfamiliarity. (Often they are other experimental artists.) In his wonderful essay “Is a Cognitive Approach to the Avant-garde Cinema Perverse?” , James Peterson identifies

a common feature of avant-garde film viewing—one that usually passes without comment: viewers initially have difficulty comprehending avant-garde films, but they learn to make sense of them. Students who take my course in the avant-garde cinema are at first completely confused by the films I show; by the end of the term, they can speak intelligently about the films they see. (110)

Audiences who enjoy such films would rather see the artist make something strange, even if the resulting work is “not as good” as a more familiar type of artwork. They enjoy being confronted with something that’s like a puzzle to figure out, a viewing experience that will initially confound and challenge them. (I of course disagree with Peterson’s use of the term avant-garde ; I would substitute for it experimental .) (But no doubt others will take issue with my use of the term experimental…)

One thing that I like about the view of the experimental that Peterson describes, and that I’m developing here, is that it’s close to the word experimental ‘s original meaning : “a test, trial, or tentative procedure; an act or operation for the purpose of discovering something unknown or of testing a principle, supposition, etc.” (Both experiment and experience share a root with peril .)

Furthermore, this view of experimental art does not require that the art or artist do anything new per se; it requires only that the art and artist be out of step with the dominant techniques and styles of the moment, preferring the unfamiliar to the familiar. (This helps explain why outsider art , née Art Brut , is often valued by experimentalists.) And this definition is comfortable with artworks like The Matrix or Harry Potter , which it admits employ innovative and unfamiliar concepts and styles, but doesn’t go on to claim as experimental . The innovations in those works are relatively minor features in regard to the whole, and ultimately dominated by other, familiar aspects of the work—more recognizable forms and concepts. Harry Potter is at heart a fairly familiar kind of novel. J.K. Rowling’s innovations lie in hybridizing genre, and not with, say, grammar (a la Stein) or novel structure (a la Cortázar).

Finally, this concept of experimental art helps explain why such art often stops being experimental. As time goes on, the artwork loses its unfamiliarity. This is why students scratching film emulsion today in imitation of Stan Brakhage are not making experimental cinema: they’re working within a known tradition, and not seeking to maximize their works’ unfamiliarity. (To be fair, many people remain sadly unfamiliar with Brakhage’s work, so a scratch film in 2010 might still blow a lot of minds. One must allow for context.) The experienced experimental film fan, meanwhile, always seeking new challenges, will sniff disdainfully when confronted with such work—”It’s so imitative!”—and go look for something he hasn’t seen before. Hence the pervasive emphasis in experimental art circles on novelty (real or imagined).

Of course, as time goes on, we may continue to enjoy previously experimental artworks. Stan Brakhage’s scratched films opened up my mind to a new aspect of cinema, and showed me a kind of beauty I hadn’t before then suspected existed. I appreciate that, and respect his films for their historical import. And I think that they continue to look rather pretty—although that’s an example of my liking them for the ways in which they’re familiar: canonical, rather than experimental .

Similarly, John Cage’s 4’33” initially confounded me—”Surely he can’t be serious! That isn’t art!” But after performing it dozens if not hundreds of times myself, I now consider it an old friend.

(Of course, 4’33” always shows you something new—especially when you perform it outside the concert hall. That’s part of what makes it such a great experimental artwork.) (That’s also why people have been looking at nature for millennia.)

Elsewhere, some experimental artworks don’t outlive their experimentation. In that case, one is free to do with them as the Zen monks advise that we do, when confronted by koans. Or as Wittgenstein put it so famously, at the end of his Tractatus :

My propositions are elucidatory in this way: he who understands me finally recognizes them as senseless, when he has climbed out through them, on them, over them. (He must so to speak throw away the ladder, after he has climbed up on it.) (189)

Works Cited

- Călinescu, Matei. Five Faces of Modernity: Modernism, Avant-Garde, Decadence, Kitsch, Postmodernism . Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1987.

- Jakobson, Roman. “The Dominant.” Language in Literature . Trans. Krystyna Pomorska. Eds. Krystyna Pomorska and Stephen Rudy. Boston: Belknap Press, 1990.

- Kermode, Frank. The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Fiction . New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.

- Peterson, James. “Is a Cognitive Approach to the Avant-garde Cinema Perverse?” Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies. Ed. David Bordwell and Noël Carroll. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996.

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus . Trans. C.K Ogden. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1922.

A. D. Jameson is the author of five books, most recently I FIND YOUR LACK OF FAITH DISTURBING: STAR WARS AND THE TRIUMPH OF GEEK CULTURE and CINEMAPS: AN ATLAS OF 35 GREAT MOVIES (with artist Andrew DeGraff). Last May, he received his Ph.D. in Creative Writing from the Program for Writers at UIC.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Related Posts

Jamming Their Transmission, Episode 20: A Conversation About Post-Post Human

From the Archives: Ten Cigarettes My Cigarette Parts Open Up My Throat Doctor, by Nick Francis Potter

Literature as Time-Space Travel: On DeWitt Henry’s Foundlings: Found Poems from Prose

Andrei Tarkovsky on Art, Life, Writing, Cinema, and More

32 thoughts on “ what is experimental art ”.

I attended a performance of 4’33” recently, at a Cage event including the screening of Cage/Cunningham. It was lovely. What’s been your favorite recital?

Back in 2007, the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts in Philadelphia, PA, had a “Pay-To-Play!” fundraiser to inaugurate “the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ.” You could pay $25/minute or $75 for five minutes to play this “King of Instruments”—”a versatile 6,938-pipe beast with wide tonal palette and ‘heft'” (that assessment according to the organ aficionados at the Wall Street Journal ).

A friend of mine said at the time that he was going to pay $75 to play 4’33” on the thing. It actually never happened, but that’s still my favorite performance.

- Pingback: Looking for Pago Pago « BIG OTHER

- Pingback: HTMLGIANT / Mondo Review/Reflection/Notes On Inception

- Pingback: Why I Hate the Avant-Garde « BIG OTHER

- Pingback: Why I Hate the Avant-Garde, pt 2 « BIG OTHER

- Pingback: A Guide to My Writing Here at Big Other « BIG OTHER

- Pingback: Rethinking Experimental Literature / the Avant-Garde / what Henry Miller calls “the inhuman ones” | HTMLGIANT

- Pingback: Bowerbird #20: Stain Mimic Admire Perish « avian architext

- Pingback: Azazel with tail X-Men First Class « BIG OTHER

- Pingback: The Higgs-Jameson Experimental Fiction Debate, part 1 | HTMLGIANT

- Pingback: Research on experimental art « cheryline Gonsalves

I am writing a Meeting the Bar: Critique and Craft article for dVerse Poets Pub, an online community of poets, to inspire our poets to explore experimentation. The pub supports weekly opportunities for poets around the world to connect with one another, learn about craft and the cannon, and from each other. Meeting the Bar is designed to provide them with a challenge and I am writing a series over the next several months on the language poets. I would like to link to your article for further investigation. Also, I would like to quote your definition/synthesis. The article will go up this Thursday and the site usually receives several hundred views each day (they have about 200,000/year). The site is here: http://dversepoets.com/ . If you would let me know by early Wednesday I would appreciate it. Thank you for your consideration and an excellent article.

Thanks for the kind words, Anna! By all means, please feel free to link and quote away (to anything that I write).

Thanks again, Adam

Thank you very much! Once the article at dVerse has posted I will send you the link. Warm regards, Anna

Thanks! Looking forward to it.

dang this is rich….i could spend the better part of a day checking out all the vids and processing the thoughts….pre-read anna’s piece for tomorrow and chased the link over to read….intriguing…will be back…

- Pingback: Meeting the Bar: Postmodern (Prose) « dVerse

Here’s the link to the article at dVerse http://dversepoets.com/2012/10/04/meeting-the-bar-postmodern-prose/ (you’ll figure into future posts too :)). Thanks so much!

Thank you , Anna!

- Pingback: A Guide to My Writing Here at Big Other (reposted) « BIG OTHER

- Pingback: Meeting the Bar: Postmodern (Experimental) « dVerse

- Pingback: Historical Precedents in Experimental Art… and 21st Century Themes… | Experimental Media

- Pingback: Welcome to the 2014 MA Experimental Practice Website and Blog | Experimental Practice (MA)

Reblogged this on Bíboros and commented: nothing

Interesting! Thanks for the article. I would have liked to know more about experimental or avant-garde art in contemporary pop culture (music, literature, any other art form)

- Pingback: ‘Experimentation’ Introduction | SKYLA EARDLEY

Adam, Great article!! Working on a senior thesis art film in NC. Wanted to give you a shoutout to thank you for your information and insight–keep writing! :)

- Pingback: Experimental Art | Experimental Film

- Pingback: Week 6, day 5 – Aug 4th! – Create Camps @ CAM

- Pingback: Experimental illustration and style – UH MA Illustration (Online) :: Research & Enquiry

- Pingback: The Rise Of Pop Art In The 1950s – laurarusso.com

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from big other.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

WHAT IS EXPERIMENTAL DRAWING?

"...that awareness of means should stimulate areas of the imaginations not otherwise accessible"1

Stanley William Hayter, founder and director of the internationally famed Atelier 17, introduced the artists who came to work with him in his print workshop to a multitude of experimental drawing methods. What then is "experimental drawing"? It is drawing in which one follows a certain process without being able to anticipate the consequences; indeed, the results obtained are essentially determined by the process itself. It is somewhat like performing an experiment in science, where you know how to proceed but do not know what will be the outcome. (in science, however, unlike experimental drawing, it is precisely those results which are not artifacts of the adopted experimental process which are of significance.) In this book we shall examine some of these processes - or "games", as Hayter preferred to call them - playful processes, ranging from the most conscious use of coordinates to imply various dimensions of space to the most unconscious (but not random) ways of drawing that yield, in an almost involuntary way, quite novel outcomes. You can therefore, freely invent your own games - as an endless activity leading to unforeseen consequences - sometimes chaotic, sometimes unforseeably precise.

Two previous formulations of experimental drawing methods have been written in the twentieth century in Europe -- both being published almost simultaneously and both originating from members of the Bauhaus -- one by Paul Klee, the other by Kandinsky. Paul Klee expressed these with precision in his 'Pedagogical Sketchbook', but they were more richly reconstituted by his students after his death and published under the title of Das Bildnerische Denken(Thinking in Images) later translated as Thinking Eye . This publication contained his students own notes of what they could remember and Klee's own poetical, but rigourous writing. Wassily Kandinsky, on the other hand, encapsulated his ideas delicately but with mathematic rigour in his workfe Point Line to Plane , published in 1926 by the "Bauhaus Books" (edited by Walter Gropius and Moholy-Nagy) which was itself a rigorous development of his better known Concerning the Spiritual in Art, providing stimulation to many later artists reading it. Perhaps not too surprisingly - since the Bauhaus was conceived as a training ground for craftsmen - a prolific new generation of painters did not appear, although the publications themselves were already deeply illuminating and still are.

The third draft was provided by S.W. Hayter in the late fifties, his ideas only having been published in a very much abbreviated form as single chapter of the now out of print book, New Ways of Gravure . The principal mode of transmission to the many hundreds of his colleagues (who included Picasso, Miro, Giacometti, Viera da Silva, Tanguy, Dali, Chagall and such people as Motherwell, Rothko, Jackson Pollock and many others in New York), was rather by living example - a demonstration of the ways one's eye , one's hand, one's relation between conscious and unconscious can be developed in playing serious games with Art. Accordingly they all knew something of his methods of drawing, a few of the multitude of which are elaborated here in this book. They were encouraged to choose only one or two operations which they then developed in one hyper-intense, revelatory week. A different aspect thus became embodied in the work of each colleague; unfortunately, however, these have never been collectively recorded in a single publication before now.

Thus while two of the three treatises were incorporated in books, Hayter's subsisted within a living, active, ever-changing group of artists who didn't necessarily know each other,(the atelier location having changed several times during the years), but who shared a kinship in expanded expectations. One might say that Hayter was in a way like Socrates whose involved dialogues suggested that philosophy could not be written but must be experienced and communicated directly. The dialectic interaction between Hayter and his colleagues was comparable. To carry this philosophical parallel even further, we are analogous to Plato, in writing down, elaborating and extending his ideas.

All of his associates started with the experimental plate 2 (to acquaint them with etching and with his radical transformations of it) whose operations will be reformulated in terms of experimental drawing. These ideas went back to the Surrealists - and their investigations of the unconscious. Although formulated in the fifties, these avant-garde ideas prefigured, in some respects, both the spiralling D.N.A. in biology, and certain aspects of literal reflections in physics, revealed by the discovery of parity violation in fundamental particle physics. An art was thus formulated which could feel itself at ease both in the unconscious (in fact in several types of unconscious) and with creative scientists, who plunge with dynamic mathematicaly control into the unknown. There was, in the Atelier, an astonishing atmosphere, even a stratosphere of search, research, discussions and anticipations not knowing what would arise next but accepting it as the given and illuminating. One might be tempted to think that the art of the twentieth century began with the concentration on the picture plane itself, rather than on the three dimensional illusory spaces lurking behind it.

Klee, and Kandinsky in his later period, regarded it thus, Kandinsky even calling his later book Point Line to Plane. Hayter, however had a much more dynamic relation to space - regarding it both as two dimensional planes evidenced in his graven traces (which rise slightly above it), but not denying the claims of three, or perhaps four dimensional extensions, even the systematic but dizying oscillations from concave to convex which give one the impression of a stomach - jerking ride on a roller coaster. These will all be illustrated in the course of this book, the spectator's mind being involved with creation of spaces, even being trained to see gradually through what looks at first sight to be only a pattern, glimpsing the spaces slowly emerging from it. It will be perceptual, a violent exercise. Get ready! Be prepared for the new ambiguity of space and the elegant manipulation of dimensions created by interlaping co-ordinate systems. In contrast to Klee and Kandinsky, Hayter is more dynamic - his spaces visually curve, oscillating inwards and outwards, involving the spectator in the very machinations of the extended fields themselves, involving him in mirror-image inversions, topological transformations, and even in the physically impossible (but mathematically imaginable) gradual transformation from left continuously into right (a mirror can, of course, do this only discontinuously!). He plunges us into systematically controlled chaos and leads us out again in his etchings, drawings and writings on experimental drawing.

While settling in Paris, he was first involved with the artistic preoccupations of the Surrealists (see Epilogue by David Gascoyne), gaining his images from his own dreams or the dreams of others rendered concrete in myths. He later developed a more continuous relation with the unconscious, not one waiting for dreams or external reference to mythology, but one which originated in the eye and hand's movements. Sometimes his dreams or a mythological creature appear also in his later work but then suffering the distortions of a superimposed space. The unconscious in this dream-sense is no longer exclusive. In fact, his deep knowledge of science sometimes influenced his own unconscious.

Many of these approaches merge in each of his drawings, but for the purpose of simplicity, we shall identify separately the main sources which infuse his thoughts.

I. Music: Baroque music - Bach and Vivaldi - in which one can hear the independent melodies and disentangle them from their simultaneous coherence in chords, provides several precise analogies: in melodic line and graphic line, in counterpoint, in rhythm and in interpenetration of melodies leading to chords. a. Counterpoint: In music counterpoint refers to a melody added as an accompaniment to a given melody played in a specific relation to it, - changed into another key, played slower or faster, inverted, or raised or lowered in pitch. There is, however, a certain coherent3 relation between these melodies which are not totally independent. Analogically in drawing, the line - corresponding to the melody - is changed coherently in relation to its initial statement - perhaps repeated or reversed in mirror-image or expanded. Graphically one has many possibilities of making several counterpoints out of the first line which remain in some way related and which can coalesce in chords. It is a response, a carefully thought out move as in chess. B. Rhythm: Rhythm can be defined as a repetition of similar elements at regular or recognizably related intervals - somehow connected in a coherent whole; - for example, - the pulsations of beating drum, or an electric current oscillating from negative to positive, or a pendulum swinging to and fro. This will be illustrated by the rhythmic repetitions of straight lines at various intervals but also, more complexly, by curves where certain types cannot be seen as simply lying on the surface but must be understood as convex or concave relative to the observer. The spectator can himself, by a trick of perception, change this convexity into concavity, thus generating an in-and-out lability.4

II. Mathematics: As a necessity for expanded researches the geometrical form of mathematics, (rather than the algebra which generated it), was communicated to his students ( here they are students) through playful and concrete ways of constructing figures such as hyperbolas, spirals, parabolas and the curved lines which, when systematically drawn, represent curved dimensions of space. All the possibilities of turning, reversing, as well as the impossibilities of transforming into a mirror-image - however much one may turn and twist -strech the brain.

III. Natural Sciences: The intrinsic aspect of various types of fields - both geometrical and physical - rather than the isolated interaction of one object with another, was considered to be mediated via the fields. Hayter's many curved coordinates which systematically intersect each other simulate a kind of Riemannian space which, according to Einstein's four dimensional space-time, is continually being modified by matter and which, in turn, modifies the matter itself. One can actually "imagine" oneself in such a space - being pulled in differing ways by varying, dynamic distortions. Hayter could immediately grasp what scientists were in the process of doing. Indeed it coud be said that he anticipated visually certain developments in both physics and biology: in the latter, for example, his investigations into the perceptual directions of the spiral prepared him mentally for the double-spiralled nature of genetic material. Avant-garde science and avant-garde art understand and propel each other.

IV. The Unconscious is not ignorance nor is it the absence of mental faculties but it is the unknown operation of the mind which influences our activities even our ordinary drawn lines in an unexpected but rigourous way. It appears in different guises. Being associated with the Surrealists, Hayter used their techniques of allowing the unconscious to be manifested in works of art, using his own dreams, the dreams of others, and even mythologies as an inspiration for his own paintings and drawings. The spectrum between the unconscious and the conscious is here manifested in the conscious use of the unconscious dream or myth. The interplay between the random and the unconscious is suggested here in 'decology' - a random ink drop being pressed between two pages to produce a very suggestive symmetrical form. Through this the artists might find their way into their own unconscious, not as Rohschach did in suggesting that one tells stories but visually. Another possibility was "collective drawing" in which the paper was divided into the number of the participants present each seeing only the edges of their neighbours' drawing. This could scarcely lead to coherence. After that diverging from the Surrealists, he developed a sort of figurative drawing, involving looking intensely at the object and drawing without ever giving a glance to the hand involved, so that a coherent but quite different sort of line emerged. This could then be drawn upon, if one wished, while looking at it and at the hand drawing it. Later, when he had transformed the picture plane into a coherent field, he developed more elaborate controllable techniques using different ways of actually looking. This is what is referred to as an 'unconscious drawing'.

This a foretaste of what will now be elaborated at length - a host of suggestions - a subset of an infinite series of processes which can be added to by the reader.

1 S.W. Hayter ' Orientation, Direction, Cheirality, Velocity and Rhythm.The Nature and Art of Motion' (edited by Gyorgy Kepes). Studio Vista, London and New York, 1965. 2 Experimental plate: on a zinc plate each new member of the atelier carried out certain operations: from the unconscious but controlled through to conscious counterpoint developed from it, to inversion of the space to the final operation using colour. 3 'Coherent' here has two applications which function simultaneously: the one grammatical - 'consistent' 'making sense' - and it combines the meaning with the second more physical - 'having a definite relationship between parts so the system as a whole acts in concert; ordely as distinct from turbulent. 4 'Lability' unstable.

Experimental Drawing and Painting

Understanding experimental drawing and painting.

Embrace open-mindedness and curiosity . Experimental drawing and painting is all about breaking rules, trying new methods and embracing the results, no matter how unexpected.

Develop a grasp of traditional techniques before bending the rules. Fundamental skills, from proportion and perspective to colour theory, can be more effectively manipulated when understood.

Recognise the value of different mediums . Each medium, be it graphite, charcoal, acrylic, watercolour etc., has unique characteristics that can be exploited in experimental art.

Techniques in Experimental Drawing

Use non-traditional tools . Try drawing with twigs, cotton buds, string, feathers—anything is a potential tool. Understand how different tools affect texture and line quality.

Manipulate your drawing surface. Crumple paper, draw on textured surfaces, or utilise mixed-media collage as a “base” for your drawings.

Mix your drawing mediums. Use ink washes over graphite, oil pastel under watercolour, charcoal on top of acrylic.

Techniques in Experimental Painting

Incorporate non-art materials . Sand, fabric scraps, newspaper clippings can give your painting texture and depth.

Try polychromatic underpainting : Use a bright underpainting, and add layers of semi-transparent paint to create depth and interesting colour effects.

Experiment with paint application . Use palette knives, sponges, or even fingers to apply paint. Create thick impasto effects or thin glazes.

Developing Personal Investigation

Critically reflect on your experiments : Which techniques worked well? Which did not, and why? Is there a new method you want to try next?

Make a visual journal part of your investigation. Document observations, ideas, experiments, notes and reflections. This practice will help you express thoughts, track progress and develop visual literacy.

Use your experimental work to explore personal themes and concepts in your art. Your artistic voice is best developed through personal experimentation and exploration.

Balancing Observational & Experimental Drawing

By paula briggs, drawing takes many forms, and facilitating drawing encompasses a wide variety of activities. at accessart we have always tried to advocate taking a balanced view between activities which develop observational drawing skills, and activities which promote more experimental, explorative activities. at the beginning it can feel like these two areas, observational and experimental drawing, are two opposites, but you will quickly see that actually the one feeds into the other, and very soon pupils will be drawing on all the skills you have taught to develop their drawings., observational drawing, when children (and adults) say they can’t draw, or that their drawing isn’t going well, they are often making that judgement because they imagine drawing is about accurate representation. as we will see, drawing is also about experimentation and expression, but to help those who would like to develop observational drawing skills, we need to teach skills in developing how they see the world about them. seeing and drawing are so closely linked and we need to help children to slow down and really see, to enable them to draw..

Explore Drawing on AccessArt for plenty of opportunity to help your pupils develop their observational drawing skills, develop hand eye coordination, and build an understanding of what drawing can be.

These activities can be re-visited time and again (much like a warm up exercise in a pe lesson), and can be adapted for all year groups., we’d also strongly advise that you try the activities yourself, experimental drawing, of course from a child’s first scribbles as a toddler, his or her drawings are experimental in nature. continuing to feed this natural impulse is vital. many of our resources help facilitators and pupils continue this exploration and you can visit a list of some of experimental projects here ..

Our experimental drawing projects are generally about enabling children to develop their own drawing language and to make and follow their own drawing decisions. This can only begin to happen when pupils begin to build familiarity with materials and techniques, and begin to develop an understanding of what each media can do for them. So for this reason, we advocate enabling children to explore medium from a very young age, in a loosely structured session.

Which comes first: observational or experimental, accessart advocates weaving activities which support the two types of drawing amongst each other, as both activities will help develop skills in the other. try to fit in activities from the key drawing exercises during the school day or week, i.e. a ten minute continuous line exercise in the morning, or use the key drawing exercises as warm up exercises before a more experimental drawing session. generally the more experimental activities will take longer, so plan for these to take place during art-based projects..

This is a sample of a resource created by UK Charity AccessArt. We have over 1500 resources to help develop and inspire your creative thinking, practice and teaching.

Accessart welcomes artists, educators, teachers and parents both in the uk and overseas., we believe everyone has the right to be creative and by working together and sharing ideas we can enable everyone to reach their creative potential..

Lesa S April 22, 2024 @ 2:53 pm

Is there a video or presentation I can share with my district art department that underlines why and how these two types of drawing are important for students and how they are linked to other areas of learning such as writing and literacy?

Rachel April 29, 2024 @ 12:07 pm

Hi Lesa, you might find the page ‘Building Understanding in Drawing’ useful to look round: https://www.accessart.org.uk/building-understanding-in-drawing/ . We also have links to some short videos and further content on the following page: https://www.accessart.org.uk/accessartdrawing/ I hope this helps!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

IMAGES

COMMENTS

10 Experimental Drawing Processes for the Art Room. It's during this recording phase that I want to introduce more exciting, experimental drawing processes. Here are some ideas: 1. Stick down areas of collage before drawing. The artwork below shows collage which has then had white and grey paint added to it and then a charcoal drawing with ...

Experimental drawing, as opposed to traditional drawing, can be defined as the study of purely making marks on a surface. It is both a sensory and physical activity, which has recently been widened to include artwork created in various media .

In this first video I stretch the surface into experimental drawing. Anyone can join in, young, old, experienced or first attempt at drawing.

Furthermore, experimental art often draws on the same materials that non-experimental art does. Here's an example of Donald Barthelme, Batman comic books, Tim Burton, William Castle, German Expressionism, J.D. Salinger, and Mark Twain all drawing inspiration, to some extent or another, from the same Victor Hugo story (sometimes directly, and ...

Art 3380 - Experimental Drawing Experimental Drawing explores the boundaries of traditional approaches in drawing media. The course is designed to ask questions about what a drawing is, explore the conventions of drawing, and experiment with unfamiliar/unexpected materials, methods, theories and presentations in the medium of drawing.

Nov 9, 2024 - Explore Eileen M. Begley's board "Experimental Drawing" on Pinterest. See more ideas about drawings, art lessons, art inspiration.

What then is "experimental drawing"? It is drawing in which one follows a certain process without being able to anticipate the consequences; indeed, the results obtained are essentially determined by the process itself. It is somewhat like performing an experiment in science, where you know how to proceed but do not know what will be the ...

Experimental drawing and painting is all about breaking rules, trying new methods and embracing the results, no matter how unexpected. Develop a grasp of traditional techniques before bending the rules. Fundamental skills, from proportion and perspective to colour theory, can be more effectively manipulated when understood. ...

Experimental Drawing Of course from a child's first scribbles as a toddler, his or her drawings are experimental in nature. Continuing to feed this natural impulse is vital. Many of our resources help facilitators and pupils continue this exploration and you can visit a list of some of experimental projects here.

frameworks to incorporate chance, collaboration, and time through experimental techniques and approaches using a variety of drawing media. Objectives: - To experiment with notions of what drawing is and what it can be. - To develop your knowledge of a variety of drawing mediums, collage, and transfer techniques.