Unilever—A Case Study

This article considers key issues relating to the organization and performance of large multinational firms in the post-Second World War period. Although foreign direct investment is defined by ownership and control, in practice the nature of that "control" is far from straightforward. The issue of control is examined, as is the related question of the "stickiness" of knowledge within large international firms. The discussion draws on a case study of the Anglo-Dutch consumer goods manufacturer Unilever, which has been one of the largest direct investors in the United States in the twentieth century. After 1945 Unilever's once successful business in the United States began to decline, yet the parent company maintained an arms-length relationship with its U.S. affiliates, refusing to intervene in their management. Although Unilever "owned" large U.S. businesses, the question of whether it "controlled" them was more debatable.

Some of the central issues related to the organization and performance of multinationals after the Second World War can be illustrated by studying the case of Unilever in the United States. Since Unilever's creation in 1929 by a merger of British and Dutch soap and margarine companies, 1 it has ranked as one of Europe's, and the world's, largest consumer-goods companies. Its sales of $45,679 million in 2000 ranked it fifty-fourth by revenues in the Fortune 500 list of largest companies for that year.

A Complex Organization

Unilever was an organizational curiosity in that, since 1929, it has been headed by two separate British and Dutch companies—Unilever Ltd. (PLC after 1981), and Unilever N.V.—with different sets of shareholders but identical boards of directors. An "Equalization Agreement" provided that the two companies should at all times pay dividends of equivalent value in sterling and guilders. There were two head offices—in London and Rotterdam—and two chairmen. Until 1996 the "chief executive" role was performed by a three-person Special Committee consisting of the two chairmen and one other director.

Beneath the two parent companies a large number of operating companies were active in individual countries. They had many names, often reflecting predecessor firms or companies that had been acquired. Among them were Lever; Van den Bergh & Jurgens; Gibbs; Batchelors; Langnese; and Sunlicht. The name "Unilever" was not used in operating companies or in brand names. Lever Brothers and T. J. Lipton were the two postwar U.S. affiliates. These national operating companies were allocated to either Ltd./PLC or N.V. for historical or other reasons. Lever Brothers was transferred to N.V. in 1937, and until 1987 (when PLC was given a 25 percent shareholding) Unilever's business in the United States was wholly owned by N.V. Unilever's business, and, as a result, counted as part of Dutch foreign direct investment (FDI) in the country. Unilever and its Anglo-Dutch twin Royal Dutch Shell formed major elements in the historically large Dutch FDI in the United States. 2 However, the fact that all dividends were remitted to N.V. in the Netherlands did not mean that the head office in Rotterdam exclusively managed the U.S. affiliates. The Special Committee had both Dutch and British members, and directors and functional departments were based in both countries and had managerial responsibilities without regard for the formality of N.V. or Ltd./PLC ownership. Thus, while ownership lay in the Netherlands, managerial control was Anglo-Dutch.

The organizational complexity was compounded by Unilever's wide portfolio of products and by the changes in these products over time. Edible fats, such as margarine, and soap and detergents were the historical origins of Unilever's business, but decades of diversification resulted in other activities. By the 1950s, Unilever manufactured convenience foods, such as frozen foods and soup, ice cream, meat products, and tea and other drinks. It manufactured personal care products, including toothpaste, shampoo, hairsprays, and deodorants. The oils and fats business also led Unilever into specialty chemicals and animal feeds. In Europe, its food business spanned all stages of the industry, from fishing fleets to retail shops. Among its range of ancillary services were shipping, paper, packaging, plastics, and advertising and market research. Unilever also owned a trading company, called the United Africa Company, which began by importing and exporting into West Africa but, beginning in the 1950s, turned to investing heavily in local manufacturing, especially brewing and textiles. The United Africa Company employed around 70,000 people in the 1970s and was the largest modern business enterprise in West Africa. 3 Unilever's total employment was over 350,000 in the mid-1970s, or around seven times larger than that of Procter & Gamble (hereafter P&G), its main rival in the U.S. detergent and toothpaste markets.

A World-wide Investor

An early multinational investor, by the postwar decades Unilever possessed extensive manufacturing and trading businesses throughout Europe, North and South America, Africa, Asia, and Australia. Unilever was one of the oldest and largest foreign multinationals in the United States. William Lever, founder of the British predecessor of Unilever, first visited the United States in 1888 and by the turn of the century had three manufacturing plants in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Philadelphia, and Vicksburg, Mississippi. 4 The subsequent growth of the business, which was by no means linear, will be reviewed below, but it was always one of the largest foreign investors in the United States. In 1981, a ranking by sales revenues in Forbes put it in twelfth place. 5

Unilever's longevity as an inward investor provides an opportunity to explore in depth a puzzle about inward FDI in the United States. For a number of reasons, including its size, resources, free-market economy, and proclivity toward trade protectionism, the United States has always been a major host economy for foreign firms. It has certainly been the world's largest host since the 1970s, and probably was before 1914 also. 6 Given that most theories of the multinational enterprise suggest that foreign firms possess an "advantage" when they invest in a foreign market, it might be expected that they would earn higher returns than their domestic competitors. 7 This seems to be the general case, but perhaps not for the United States. Considerable anecdotal evidence exists that many foreign firms have experienced significant and sustained problems in the United States, though it is also possible to counter such reports with case studies of sustained success. 8

During the 1990s a series of aggregate studies using tax and other data pointed toward foreign firms earning lower financial returns than their domestic equivalents in the United States. 9 One explanation for this phenomenon might be transfer pricing, but this has proved hard to verify empirically. The industry mix is another possibility, but recent studies have suggested this is not a major factor. More significant influences appear to be market share position—in general, as a foreign owned firm's market share rose, the gap between its return on assets and those for United States—owned companies decreased—and age of the affiliate, with the return on assets of foreign firms rising with their degree of newness. 10 Related to the age effect, there is also the strong, but difficult to quantify, possibility that foreign firms experienced management problems because of idiosyncratic features of the U.S. economy, including not only its size but also the regulatory system and "business culture." The case of Unilever is instructive in investigating these matters, including the issue of whether managing in the United States was particularly hard, even for a company with experience in managing large-scale businesses in some of the world's more challenging political, economic, and financial locations, like Brazil, India, Nigeria, and Turkey.

The story of Unilever in the United States provides rich new empirical evidence on critical issues relating to the functioning of multinationals and their impact. — Geoffrey Jones

Finally, the story of Unilever in the United States provides rich new empirical evidence on critical issues relating to the functioning of multinationals and their impact. It raises the issue of what is meant by "control" within multinationals. Management and control are at the heart of definitions of multinationals and foreign direct investment (as opposed to portfolio investment), yet these are by no means straightforward concepts. A great deal of the theory of multinationals relates to the benefits—or otherwise—of controlling transactions within a firm rather than using market arrangements. In turn, transaction-cost theory postulates that intangibles like knowledge and information can often be transferred more efficiently and effectively within a firm than between independent firms. There are several reasons for this, including the fact that much knowledge is tacit. Indeed, it is well established that sharing technology and communicating knowledge within a firm are neither easy nor costless, though there have not been many empirical studies of such intrafirm transfers. 11 Orjan Sövell and Udo Zander have recently gone so far as to claim that multinationals are "not particularly well equipped to continuously transfer technological knowledge across national borders" and that their "contribution to the international diffusion of knowledge transfers has been overestimated. 12 This study of Unilever in the United States provides compelling new evidence on this issue.

Lever Brothers In The United States: Building And Losing Competitive Advantage

Lever Brothers, Unilever's first and major affiliate, was remarkably successful in interwar America. After a slow start, especially because of "the obstinate refusal of the American housewife to appreciate Sunlight Soap," Lever's main soap brand in the United Kingdom, the Lever Brothers business in the United States began to grow rapidly under a new president, Francis A. Countway, an American appointed in 1912. 13 Sales rose from $843,466 in 1913, to $12.5 million in 1920, to $18.9 million in 1925. Lever was the first to alert American consumers to the menace of "BO," "Undie Odor," and "Dishpan Hands," and to market the cures in the form of Lifebuoy and Lux Flakes. By the end of the 1930s sales exceeded $90 million, and in 1946 they reached $150 million.

By the interwar years soap had a firmly oligopolistic market structure in the United States. It formed part of the consumer chemicals industry, which sold branded and packaged goods supported by heavy advertising expenditure. In soap, there were also substantial throughput economies, which encouraged concentration. P&G was, to apply Alfred D. Chandler's terminology, "the first mover"; among the main followers were Colgate and Palmolive-Peet, which merged in 1928. Neither P&G nor Colgate Palmolive diversified greatly beyond soap, though P&G's research took it into cooking oils before 1914 and into shampoos in the 1930s. Lever made up the third member of the oligopoly. The three firms together controlled about 80 percent of the U.S. soap market in the 1930s. 14 By the interwar years, this oligopolistic rivalry was extended overseas. Colgate was an active foreign investor, while in 1930 P&G—previously confined to the United States and Canada—acquired a British soap business, which it proceeded to expand, seriously eroding Unilever's market share. 15

The soap and related markets in the United States had a number of characteristics. Although P&G had established a preponderant market share, shares were strongly contested. Entry, other than by acquisition, was already not really an option by the interwar years, so competition took the form of fierce rivalry between incumbent firms with a long experience of one another. During the 1920s and the first half of the 1930s, Lever made substantial progress against P&G. Lever's sales in the United States as a percentage of P&G's sales rose from 14.8 percent between 1924 and 1926 to reach almost 50 percent in 1933. In 1930 P&G suggested purchasing Lever in the United States as part of a world division of markets, but the offer was declined. 16 Lever's success peaked in the early 1930s. Using published figures, Lever estimated its profit as a percentage of capital employed at 26 percent between 1930 and 1932, compared with P&G's 12 percent.

Countway's greatest contribution was in marketing. During the war, Countway put Lever's resources behind Lux soapflakes, promoted as a fine soap that would not damage delicate fabrics just at a time when women's wear was shifting from cotton and lisle to silk and fine fabrics. The campaign featured a variety of tactics, including washing demonstrations at department stores. In 1919 Countway launched Rinso soap powder, coinciding with the advent of the washing machine. In the same year, Lever's agreement with a New York agent to sell its soap everywhere beyond New England was abandoned and a new sales organization was established. Finally, in the mid-1920s, Countway launched, against the advice of the British parent company, a white soap, called "Lux Toilet Soap." J. Walter Thompson was hired to develop a marketing and advertising campaign stressing the glamour of the new product, with very successful results. 17 Lever's share of the U.S. soap market rose from around 2 percent in the early 1920s to 8.5 percent in 1932. 18 Brands were built up by spending heavily on advertising. As a percentage of sales, advertising averaged 25 percent between 1921 and 1933, thereby funding a series of noteworthy campaigns conceived by J. Walter Thompson. This rate of spending was made possible by the low price of oils and fats in the decade and by plowing back profits rather than remitting great dividends. By 1929 Unilever had received $12.2 million from its U.S. business since the time of its start, but thereafter the company reaped benefits, for between 1930 and 1950 cumulative dividends were $50 million. 19

Many foreign firms have experienced significant and sustained problems in the United States. — Geoffrey Jones

After 1933 Lever encountered tougher competition in soap from P&G, though Lever's share of the total U.S. soap market grew to 11 percent in 1938. P&G launched a line of synthetic detergents, including Dreft, in 1933, and came out with Drene, a liquid shampoo, in 1934 both were more effective than solid soap in areas of hard water. However, such products had "teething problems," and their impact on the U.S. market was limited until the war. Countway challenged P&G in another area by entering branded shortening in 1936 with Spry. This also was launched with a massive marketing campaign to attack P&G's Crisco shortening, which had been on sale since 1912. 20 The attack began with a nationwide giveaway of one-pound cans, and the result was "impressive." 21 By 1939 Spry's sales had reached 75 percent of Crisco's, but the resulting price war meant that Lever made no profit on the product until 1941. Lever's sales in general reached as high as 43 percent of P&G's during the early 1940s, and the company further diversified with the purchase of the toothpaste company Pepsodent in 1944. Expansion into margarine followed with the purchase of a Chicago firm in 1948.

The postwar years proved very disappointing for Lever Brothers, for a number of partly related reasons. Countway, on his retirement in 1946, was replaced by the president of Pepsodent, the thirty-four-year-old Charles Luckman, who was credited with the "discovery" of Bob Hope in 1937 when the comedian was used for an advertisement. Countway was a classic "one man band," whose skills in marketing were not matched by much interest in organization building. He never gave much thought to succession, but he liked Luckman. 22 This proved a misjudgment. With his appointment by President Truman to head a food program in Europe at the same time, Luckman became preoccupied with matters outside Lever for a significant portion of his term, though perhaps not to a sufficient degree. Convinced that Lever's management was too old and inbred, he dismissed about 15 percent of the work force soon after taking office, and he completed the transformation by moving the head office from Boston to New York, taking only around one-tenth of the existing executives with him. 23 The head office, constructed in Cambridge by Lever in 1938, was subsequently acquired by MIT and became the Sloan Building.

Luckman's move, which was supported by a firm of management consultants, the Fry Organization of Business Management Experts, was justified on the grounds that the building in Cambridge was not large enough, that it would be easier to find the right personnel in New York, and that Lever would benefit by being closer to the large advertising agencies in the city. 24 There were also rumors that Luckman, who was Jewish, was uncomfortable with what he perceived as widespread anti-Semitism in Boston at that time. The cost of building the New York Park Avenue headquarters, which became established as a "classic" of the new postwar skyscraper, rose steadily from $3.5 million to $6 million. Luckman had trained as an architect at the University of Illinois, and he was very involved in the design of the pioneering New York office.

- 25 Jun 2024

- Research & Ideas

Rapport: The Hidden Advantage That Women Managers Bring to Teams

- 11 Jun 2024

- In Practice

The Harvard Business School Faculty Summer Reader 2024

How transparency sped innovation in a $13 billion wireless sector.

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

- 27 Jun 2016

These Management Practices, Like Certain Technologies, Boost Company Performance

- Globalization

- Consumer Products

- Entertainment and Recreation

- Food and Beverage

- Manufacturing

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Share Podcast

How Unilever Is Preparing for the Future of Work

How should the consumer goods company upscale its global workforce for the future?

- Apple Podcasts

Launched in 2016, Unilever’s Future of Work initiative aimed to accelerate the speed of change throughout the organization and prepare its workforce for a digitalized and highly automated era. But despite its success over the last three years, the program still faces significant challenges in its implementation. How should Unilever, one of the world’s largest consumer goods companies, best prepare and upscale its workforce for the future? How should Unilever adapt and accelerate the speed of change throughout the organization? Is it even possible to lead a systematic, agile workforce transformation across several geographies while accounting for local context?

Harvard Business School professor and faculty co-chair of the Managing the Future of Work Project William Kerr and Patrick Hull , Unilever’s vice president of global learning and future of work, discuss how rapid advances in artificial intelligence, machine learning, and automation are changing the nature of work in the case, “ Unilever’s Response to the Future of Work .”

BRIAN KENNY: On November 30, 2022, OpenAI launched the latest version of ChatGPT, the largest and most powerful AI chatbot to date. Within a few days, more than a million people tested its ability to do the mundane things we really don’t like to do, such as writing emails, coding software, and scheduling meetings. Others upped the intelligence challenge by asking for sonnets and song lyrics, and even instructions on how to remove a peanut butter sandwich from a VCR in the style of King James. But once the novelty wore off, the reality set in. ChatGPT is a game changer, and yet another example of the potential for AI to change the way we live and work. And while we often view AI as improving how we live, we tend to think of it as destroying how we work, fears that are fueled by dire predictions of job eliminations in the tens of millions and the eradication of entire industries. And while it’s true that AI will continue to evolve and improve, eventually taking over many jobs that are currently performed by people, it will also create many work opportunities that don’t yet exist. Today on Cold Call , we welcome Professor William Kerr, joined by Patrick Hull of Unilever, to discuss the case, “Unilever’s Response to the Future of Work.” I’m your host, Brian Kenny, and you’re listening to Cold Call on the HBR Podcast Network. Professor Bill Kerr is the co-director of Harvard Business School’s Managing the Future of Work initiative. His research centers on how companies and economies explore new opportunities and generate growth, and he is a fellow podcaster. He hosts a show called Managing the Future of Work . Bill, thanks for being here.

Bill Kerr: Thanks for having us.

BRIAN KENNY: And Patrick Hull is Unilever’s VP of Global Learning and Future of Work. He goes by Paddy. Paddy, thanks for joining us.

PATRICK HULL: Thank you very much for having me.

BRIAN KENNY: It’s great to have you both here today. I think people will really be interested in hearing this case and how Unilever is thinking about the future of work. So why don’t we just dive right in. And, Bill, I’m going to ask you to start by telling us what the central issue is in the case, and what your cold call is to start the discussion in class.

Bill Kerr: Well, Brian, I think your introduction clearly outlined the central issue, which is technology is really transforming the world of work. And that means, companies must learn how to do things different than what they’ve done over 50 or a hundred year history. And it also means they must transform the skill base in how they’re approaching employees and talent. I think we can simply say: that ain’t easy, and it’s also going to introduce significant challenges and tensions for organizations. A big company like Unilever is going to really want to appeal to employees, put the purpose of the company in front of employees, embrace that, but it’s also going to have to make challenging decisions regarding employees and their transition of skills and what’s the future workforce going to look like. So the most common cold call is a really simple question, which is: has Unilever, through its Future of Work Program, resolved the paradox of profit and purpose? And pretty quickly, the answer to that is, “no.” It hasn’t fully resolved that. I will occasionally get maybe one person that goes all the way there. So then we’ve got to start unpacking, okay, how close is it to resolving that? And are we very near the end point or are we farther away?

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. Simple question to you maybe, but probably not to others who are listening. That sounds like a pretty complex question. I mentioned your involvement with the Managing the Future of Work initiative here. So I know you think a lot about this. This is on your mind all the time. How did you hear about what Unilever was doing, and why was it important to you to write this case?

Bill Kerr: Well, it’s interesting. The history of the connection came through another case that we wrote. Very early in our project on Managing the Future of Work , we’re always very deliberate about putting the “managing” in front of the future of work, and that we want to think about how leading companies are reacting to the forces that are shaping the future, like digitization and demographic changes and so forth. So, we’ve written a case about Vodafone, which we did a Cold Call a while back. With Vittorio Colao. And Vittorio was on Unilever’s board and said, “You have got to go and meet this organization and see what they’re doing,” because they have one of the most comprehensive, well thought out programs for the future of work that he had come across. And in fact, that was the connection that then followed on. And yes, for a sector that Unilever’s working in that has end-to-end change going on from the manufacturers, all the way down through the consumers or the products, to be able to have an organization that’s thought very deeply about what pillars do we need to put into place to make the change occur is great. The other thing that was delightful about Unilever and writing this case study is that, a lot of times, companies want to talk about their programs, only after they know that it was a success. They would prefer to wait until they’ve… They’re like, wait another two years and then we’ll write the case study about this transformation. But Unilever’s been very upfront in saying, “The future of work’s a big challenge. We have to get in front of that. Here’s what we’re doing. We haven’t necessarily figured it all out yet, and some of this will prove wildly successful. Others may be challenging, but this is where we’re going.” And that’s been a great thing to really spark a lot of executives and students a conversation about, what will the future of work require, and how can we get there?

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. So, Patty, I have to ask, I have to start by asking you, what’s your job? Because your title’s very lofty. It basically calls you a visionary. You are the VP of Global Learning and Future of Work. So what do you do?

PATRICK HULL: I’ve got a funny answer to that question. Since the pandemic, and obviously, been working a lot from home, and I work in a slightly open area, so my wife gets to hear a little bit of what I’m talking about. She seems to think that what I do is laugh a lot and chat a lot to people. So that’s what-

BRIAN KENNY: Kind of like we’re doing today. So, she’s listening in…

PATRICK HULL: She says, “When do you do some real work?” But yes, I guess what I do is work with a really passionate, dedicated team of people who are looking at how are we preparing our organization, and our people in particular, for a future that is very different to what we’ve been experiencing in our traditional work models up to this point. You mentioned ChatGPT as well. I mean, that really is the talk of the town at the moment. And I guess we’ve been thinking for a bit of time, as Bill mentioned, about the impact of things like that on our business, and trying to get on the forefront of what’s our response to that. So I wouldn’t quite say visionary. I think, at this stage in business and what’s going on, it’s quite hard to be truly visionary, but trying to stay one or two steps slightly ahead of what’s going on in the world of work, that’s, I guess, what my job’s all about.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. That’s great. For our listeners who… I think most people have heard of Unilever, but for people who aren’t really aware of the scope and scale of Unilever, can you describe the business for us a little bit?

PATRICK HULL: Yes. So we’re a fast moving consumer goods business. So most of you will probably interact with one of our brands or products every day. In fact, we say that we serve 3.4 billion people every day. That’s how often someone buys one of our products or uses one of our products. We’ve got about 400 brands in 190 countries across the world, ranging from global brands like Dove, Sunsilk, Hellmann’s, Rexona, all the way through to what we call local jewels like Marmite in the UK, which is one of those brands that you either love it or hate it.

BRIAN KENNY: How big is the workforce at Unilever?

PATRICK HULL: The workforce is about 149,000 people who are directly employed by us. But we always often speak about how we have an extended workforce of around 3 to 5 million people, who if you ask them who they work for, they would say Unilever, even though they’re actually employed by someone else.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. So we know Unilever well at Harvard Business School. We’ve had lots of cases written on over the years by our faculty, and we’ve actually talked about it on Cold Call before, particularly, the focus on sustainability. Unilever really stands out in this regard. And I wonder if you could talk a little bit about how important this is to the culture at Unilever.

PATRICK HULL: It is. I can’t tell you how important it is. In fact, when Paul Polman, previous CEO, came into the organization in 2009, he launched the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan in 2010. And he did this beautiful job when he launched it of reminding us that sustainability has been part of Unilever since day one. When Lord Leverhulme started selling Sunlight soap, his mission was to make cleanliness commonplace. That was back in the late 1800s. And what Paul did beautifully is he then simply shifted that a little bit and said, “We are now here to make sustainable living commonplace, because now we impact so many more people and so many more homes. If we can help every consumer out there make more sustainable choices with how they eat, how they clean, how they use plastic, how they use water, then we can have a massive impact, positive impact, on the planet and society, and that’s good for business.” That was the business model that we’ve ascribed to. So we hire on it. We are tracked on it. We develop on it. It’s definitely part of the way things get done here.

BRIAN KENNY: Bill, let me turn back to you for a second. The FMCG sector is fast moving, as it indicates. What are some of the forces that are putting pressure on that particular sector these days?

Bill Kerr: Yeah. The case outlines three forces, and let me walk through those and also say a little bit of, before I do that, why we think this sector’s amazing to watch. If you want to have a kind of front row seat as to how the future of work may play out in other sectors, I often direct them towards the fast moving consumer good sector because the technology forces, the demographic forces, the gig workplace force that we’ll talk about are all happening already. They’re deep into this sector, so we can learn a lot from it. So, the first one is clearly technology that links through all the way to our opening conversation. There’s many ways in which the touch points between consumers and the outlets and last mile delivery and drones possibly dropping off future packages reverberates all the way up through the supply chain to Unilever and its suppliers above. A simple kind of easy metric is, think about the speed that we now demand or expect of our package delivery. It’s no longer that we’re going to go to the store and pick this up and the store can replenish itself over a week-long horizon. It’s going to be, I just pressed the button in the app and I’m expecting it in the next five minutes to be handed to me. That puts a lot of demands on how an organization needs to function, and also increase the expectation about the customization and the personalized products that consumers will require. So, the technology requires Unilever to think differently. The second is a broader force, but equally as impactful, and even more predictable for the future, which is the role of aging populations and demographic change in the workplace that is quite different than the workplace of the 20th century, where many of the large companies today kind of got their grounding. One of the early kind of points that it makes is that, in the UK, about a third of the workforce currently is over the age of 50, and that’s true in most every advanced economy, as well as also, increasingly across East Asia and elsewhere, that we have older populations. We have workforces that are going to span many more generations in the workplace. And then the third one, which in our project, Managing the Future of Work , we think of as kind of an outcome of tech and demographics coming together is the gig workplace. Paddy talked about the extended workforce beyond Unilever, and the case tries to unpack some of the ways they’re approaching bringing people to work that aren’t the traditional full-time jobs that most companies got built up around. And the gig workplace is activated by that technology that lets us schedule and involve people in gig works. And also, as we think about low unemployment rates and older populations and tacked out and so forth, the degree that we can, as a company, attract in people that are currently not working or at the edge of working and tempt them to come work for us on projects is a very valuable labor supply to these organizations.

BRIAN KENNY: Paddy, you’re in it, literally. So what are you seeing as some of the things that have shifted over time?

PATRICK HULL: So, when I started, I’m going to give my age away here a little bit, but back in the 1990s, I remember us talking a lot about, how could we get direct to the consumer? Back in those days, we sold everything through big box retail, and it was all about maintaining those relationships, making sure you had great store shelf positioning and great relationships with those buyers. One of the most massive shifts is that direct to consumer is the channel now. Bill spoke about how we all just order stuff off Amazon directly. We don’t have any advantage anymore in terms of getting to consumers. You and I, any little startup, can throw some ads on Instagram, speak to a few influencers and start sending their products out. So the whole game has changed in terms of how are we reaching people.

BRIAN KENNY: And I can already imagine, just based on the examples you’ve both given, I’m already seeing areas where there would be churn in the workforce around some of these developments. So let’s talk a little bit about Unilever’s Future of Work plans. And there’s a framework that goes along with it. I wonder if you could describe that and talk about the three pillars that support that framework.

PATRICK HULL: Yes, our three pillars are: change the way we change, ignite lifelong learning, and redefining the Unilever system of work. And I’ll explain a little bit about each of those. So changing the way we change. The first one is, what we’ve realized is that change is continuous. Disruption is continuous in our organization. It’s not about standalone moments where we see that, oh, we need to shut down a factory or change something because of a dramatic shift. Change is happening all the time. All of our factories are rapidly automating all of our office processes, so we can’t stick to the old traditional model of change, which was a very slow moving consultative approach, and also, where management held its cards close to its chest until sort of the last moment and then announced, “This is happening.” We’ve realized that, really, to be true to our purpose around making sustainable living commonplace, we need to enter into a far more open, early, proactive dialogue with our people around the change that’s affecting our organization, and how to help start preparing them well in advance of any actual impact on them in terms of how they can prepare for that change. So that’s the first one, changing the way we change. The second one around igniting lifelong learning is about engaging with our people to make sure that they’re all equipped to thrive, both now and into the future, and that we are showing them a bit of what that future looks like and where they need to be focusing their attention. And then the third, redefining the whole system of work is a bit of what Bill was mentioning earlier. Here, we really want to embrace this notion of accessing talent rather than owning talent. We’ve felt that if we just keep on trying to hold onto all our FTEs and compete against everyone else with talent, we are never going to have the people and the skills in our organization that we need to take us forward into the future. So we really want to redefine new models of working, so it’s not just you’re either fixed or you’re a gig worker, but how can we find some flex in the middle that helps people transition out of this traditional life cycle of work, the kind of 40-hour, 40-week, 40-year traditional employment pattern, and help get them future fit for a hundred year life, where they may want to slowly move into retirement, where they may want to spend some time looking after their kids, where they may want to set up their side hustle. How do we create that sort of flexibility?

BRIAN KENNY: There’s definitely, and understandably, a lot of emotion involved with some of these things. And I’m wondering if maybe you could give our listeners a sense, based on all the research you’ve done in the initiative, about what kinds of jobs are going to go away, and what kinds of skills you think are going to be most important for people to think about in the future?

Bill Kerr: Well, Brian, I come back with, that we don’t think of jobs really going away. And I think it’s important to instead think of jobs as a collection of tasks. And certain tasks will be taken over by the machine and require less human input, as the technology gets more advanced. And that could be in a very manual kind of sense. It could also be with ChatGPT in a more cognitive relationship. And perhaps, the thing that we’re experiencing right now that’s very front and center in the world of work is, lots of ways that technology is coming in towards more cognitive tasks that are complex, they’re non-routine. They were not able to be done by the computer before, but artificial intelligence machine learning and so forth are able to take those off. So if you think about how supply chain forecasting will happen at Unilever, that’s going to be done in a fundamentally different way than it would’ve been even 10 years ago.

BRIAN KENNY: Sure.

Bill Kerr: But we always think about new tasks emerging, and it’s hard to predict exactly what those tasks will involve. When you think about the skills, we know that having digital fluency and also social skills are the two biggest things that you can put money on, bank on, those being important enough for the future. But there’s also going to be judgment, and there’s going to need to be innovativeness. So even if the computer starts to do a really good job at predicting about how salespeople should arrange the shelves or how they should approach consumers, you still have to think about, as an organization, what data are we feeding into the system? And where could Unilever develop a proprietary data advantage? And how would we collect those data streams and put them into it? So the technology will be there, it’s going to take over evermore parts of work as it has been for 150 years at this point, but there’ll also be places where humans will be complementing and helping to achieve the goals of the company.

BRIAN KENNY: So that’s an optimistic viewpoint, Paddy. And I’m wondering what the response is from people when you start to talk about these ideas with them. And how do you move them beyond just their own insecurity and concern for themselves, to really embrace learning new skills and thinking about a different way of working in the future?

PATRICK HULL: This is a fundamental dilemma facing us, Brian. I’m so glad you asked me that question. And whilst I don’t know if we’ve cracked it, I think we’ve got a really good hypothesis around what helps this. One of the things we know is, the way not to motivate people to learn new skills is to tell them, “You better re-skill or the robots are going to take your job away.” So we’ve taken the view that if we can help people to discover their purpose, what makes them unique, how do they approach work in their own way, and then start from that point and say, “Okay, when you are at your best, you are doing these things. How do we make sure that you are developing the skills in line with that, that are going to keep you future fit in an environment that is changing around you in terms of the nature of your job and how you work?” And we’ve found that when people come from that place of purpose, they do feel far more agency over it. They are far more motivated to learn new skills, to continue to be relevant, but it’s coming from a much more positive place. It’s not coming from that fight or flight or freeze sort of mode. It’s coming from a place of agency. And in fact, we partnered with some academic institutions to measure the impact of starting people thinking about purpose and then creating future fit plans from there. And we’ve found that it does lead to people being 25% more engaged in thinking about the future, in going the extra mile, in having this intrinsic motivation to take it on. And they’re 22% more productive, which is another great benefit to us.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. So, Bill, we’ve been through situations like this before. If you look back over the long arc of history, we’ve had movement from an agrarian society to an industrial society. We’ve had manufacturing sector turned on its head when a lot of manufacturing jobs have gone overseas. And I think each time we’ve done that, there’s been a portion of the workforce that’s just not been able to make the leap to the new mode of doing things. Unilever is talking about ensuring that 80% to 100% of their workforce can be transitioned in the right way. Is that too big of a promise to make?

Well, to their credit, I believe they stayed at the pretty top end of that range so far. And I think the workshops and so forth that Paddy just outlined are best in class for trying to stay up there. I do think, Brian, you see organizations, and I’m spanning out from Unilever at this point, that are trying to set a new contract with workers, both explicitly and implicitly, that says, “Our part of the bargain is, we’re going to give you great clarity as to what roles we see the company needing in the future, and help you kind of think about where you are today and what you would need to acquire skill-wise to get to that future point. And we’re going to give you the platform to acquire those skills. But your part of the bargain has to be to put the time and the investment in to be having those skills when that time comes.” And so I think we’re seeing a shift in a bit of the, we want to be a great place for you to have worked and developed your career, but we’re not going to be guaranteeing a lifelong employment. We’re going to focus on the skills that are needed and help you make the investments and choices that should be made.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. And what does that start to look like at Unilever, Paddy? What are some of the ways that you’re sort of redefining the systems of work there?

PATRICK HULL: So, one of the big initiatives that we’ve undertaken was this whole idea of, how do we help people create more flexibility in their roles, so that they can discover new ways of working, discover new skills, grow in new and different ways? And I mentioned to you earlier that we thought there’s this sort of gridlock that, on the one hand, you’ve got full-time employees, you’ve got lots of security, but no flexibility in terms of how and where they work. And on the other hand, you’ve got gig workers, freelancers, lots of flexibility, but not much security in terms of guaranteed income. And we’ve set ourselves a challenge of, how do we create this responsible alternative to the gig economy? And our idea was something called U-Work. U-Workers no longer have a job title. They work on gigs and projects in Unilever, but they are still 100% Unilever employees. They are not gig workers, so they’re not contractors or anything. In fact, they’re an internal pool of contractors, if you like, but they remain Unilever employees. They get a guaranteed retainer. They get a package of social care, pension benefits, healthcare benefits. And they get a learning stipend. But in return for that, they then only need to work on projects. They can set up their own business on the side. They can look after their kids or aging parents, or they can gradually move into retirement. And I think it’s this kind of thing that we need to continue to explore, as we see in the impact of automation and digitization, and also this trend or this desire for people to have more flexibility to choose how and when they work.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. It actually sounds kind of appealing. So you also get variety that goes along with that. You get to move from one project to another, and you’re not sort of locked in on the same kinds of things, all the time.

PATRICK HULL: And, Brian, the one thing, just to emphasize on that, people get very locked into the thing of, ah, does someone have the skill I need for the job? In fact, what we found is, one of the most important skills is knowing the organization. So U-Work is great because they are Unilever employees. They know the organization. They know how to get things done in Unilever. And we must never underestimate the power of that skill

BRIAN KENNY: Bill, it seems like anytime that we enter into one of these huge labor market transitions, manufacturing jobs, take it on the nose. And so I’m wondering, as you think about the implications for jobs in the future, what are the implications for manufacturing specifically?

Bill Kerr: Well, I think, Brian, we’re already been seeing that in motion for a while. Manufacturing has been at the forefront of technology adoption for decades. I think time will tell how it will continue to evolve. I would anticipate more skilled, more advanced, more technology enabled, but there could also be some interesting twists. It’s not the current case study that we’re talking about, but there’s another case study at Harvard Business School, done by Raj Choudhury, our colleague, with Unilever that’s about remote manufacturing. So how can the remote workforce be connected into the manufacturing sector? So we’ll see a lot of innovation towards the future.

BRIAN KENNY: And how is Unilever thinking about that, Paddy?

PATRICK HULL: So actually, the whole genesis of this future of work framework was done together, well, co-created together with our European Works Council actually, so our manufacturing representatives coming together with management to think about, how is the future of work impacting the manufacturing environment? So actually, our whole framework came from them. So, we very much see this as a critical way of addressing the impact of digitization and automation in the manufacturing environment. We’ve found some fantastic examples where we’ve started people thinking about their roles in future. And what we’ve found is, there’s quite a strong correlation between some of the skills our manufacturing workers have and lab assistants in our R&D labs. And funnily enough, we tend to have quite big R&D centers right next to our factories. So we’ve seen quite a bit of movement of people being able to re-skill from manufacturing environment into R&D labs in a way, a more sustainable future environment, all because they’ve identified, what’s the work that they really enjoy doing, what are they really good at, and then what are the skills required to go into the future?

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. That’s a huge win-win, right? For the worker and for the firm.

PATRICK HULL: Correct.

BRIAN KENNY: This has been a great conversation. I’ve really enjoyed it. I’m wondering if… I’ve got time for one question for each of you left here. So, I’m going to start with you, Paddy. How is Unilever going to know if they’re succeeding in this? Is there a sort of an end game in mind here?

PATRICK HULL: The big goal is obviously that we are proving that our sustainable business model is more effective than others in terms of driving superior performance. So the big number is still, how are we doing as an organization? I would say the key input metrics are things like, how well are we able to re-skill our people for the future? We really believe that re-skilling is the way forward. We know it’s cheaper than recruiting from outside. It’s better for our people. It’s a way of getting people who know our business to continue to do good things. So we do measure that. How many people are we helping to transition? And then it’s about, how attractive do we continue to be as an employer for new recruits and for the people within our organization? So we’ll track the traditional input metrics like engagement, attrition, our employer brand, how well people are collaborating going forward.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. It sounds like you’re off to a fantastic start. Bill, I’ll give you the last words, since you wrote the case. If there’s one thing you’d like people to remember about this case, what is it?

Bill Kerr: Well, let me go back. We started with the cold call, so let me tell you how I end the class. There’s a video of one of Paddy’s colleagues, Nick Dalton, who is quoting President Kennedy, who was in turn quoting an Irish writer named Frank O’Connor. And Kennedy was speaking about the space mission, and Frank O’Connor was describing, as a kid, when they would come to this orchard wall that was too high for them to climb over. They had no idea how they were going to do it. They would take their hats and they would throw them over the orchard wall, so that they just committed themselves to figuring it out. And Nick basically thought of the Unilever program as a bit of, “We’re throwing our hat over the wall. We don’t know exactly how we’re going to climb over this future of work wall, but we know we must do it. And this is our public commitment to making that happen.” And the thing I’d come back to listeners around this is, the future of work is scary. And we talked about job transitions and how quickly the new technologies are coming. This time last year, we had no thought of ChatGPT as being part of this Cold Call podcast, but now, it’s what we lead with. And so, hopefully, people can unfreeze a little bit and can start thinking about, regardless of what the twists and turns may lie ahead, they need to begin a journey with their employees. And Unilever is showing, here’s how we’re approaching that. Now, let’s all work on it together.

BRIAN KENNY: Yeah. Well, I suspect I’m not alone when I say we’re rooting for you. We hope that you get this right. There’s a lot at stake.

PATRICK HULL: Thanks, Brian.

BRIAN KENNY: Thank you both for joining me.

Bill Kerr: Thanks.

BRIAN KENNY: If you enjoy Cold Call , you might like our other podcasts, After Hours , Climate Rising , Deep Purpose, IdeaCast , Managing the Future of Work , Sk ydeck , and Women at Work . Find them on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you listen, and if you could take a minute to rate and review us, we’d be grateful. If you have any suggestions or just want to say hello, we want to hear from you. Email us at [email protected] . Thanks again for joining us. I’m your host, Brian Kenny, and you’ve been listening to Cold Call , an official podcast of Harvard Business School and part of the HBR Podcast Network.

- Subscribe On:

Latest in this series

This article is about change management.

- Organizational change

- Mission statements

- Human resource services

- Retail and consumer goods

Partner Center

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

- Currently reading: Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG

- Business school teaching case study: how electric vehicles pose tricky trade dilemmas

- Business school teaching case study: is private equity responsible for child labour violations?

- Business school teaching case study: capture or cut carbon to make steel greener?

- Business school teaching case study: what does climate change mean for home insurance?

- Business school teaching case study: can biodiversity bonds save natural habitats?

- Business school teaching case study: can the fashion industry be more sustainable?

Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG

- Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG on x (opens in a new window)

- Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG on facebook (opens in a new window)

- Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG on linkedin (opens in a new window)

- Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG on whatsapp (opens in a new window)

Gabriela Salinas and Jeeva Somasundaram

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In April this year, Hein Schumacher, chief executive of Unilever, announced that the company was entering a “new era for sustainability leadership”, and signalled a shift from the central priority promoted under his predecessor , Alan Jope.

While Jope saw lack of social purpose or environmental sustainability as the way to prune brands from the portfolio, Schumacher has adopted a more balanced approach between purpose and profit. He stresses that Unilever should deliver on both sustainability commitments and financial goals. This approach, which we dub “realistic sustainability”, aims to balance long- and short-term environmental goals, ambition, and delivery.

As a result, Unilever’s refreshed sustainability agenda focuses harder on fewer commitments that the company says remain “very stretching”. In practice, this entails extending deadlines for taking action as well as reducing the scale of its targets for environmental, social and governance measures.

Such backpedalling is becoming widespread — with many companies retracting their commitments to climate targets , for example. According to FactSet, a US financial data and software provider, the number of US companies in the S&P 500 index mentioning “ESG” on their earnings calls has declined sharply : from a peak of 155 in the fourth quarter 2021 to just 29 two years later. This trend towards playing down a company’s ESG efforts, from fear of greater scrutiny or of accusations of empty claims, even has a name: “greenhushing”.

Test yourself

This is the fourth in a series of monthly business school-style teaching case studies devoted to the responsible business dilemmas faced by organisations. Read the piece and FT articles suggested at the end before considering the questions raised.

About the authors: Gabriela Salinas is an adjunct professor of marketing at IE University; Jeeva Somasundaram is an assistant professor of decision sciences in operations and technology at IE University.

The series forms part of a wider collection of FT ‘instant teaching case studies ’, featured across our Business Education publications, that explore management challenges.

The change in approach is not limited to regulatory compliance and corporate reporting; it also affects consumer communications. While Jope believed that brands sold more when “guided by a purpose”, Schumacher argues that “we don’t want to force fit [purpose] on brands unnecessarily”.

His more nuanced view aligns with evidence that consumers’ responses to the sustainability and purpose communication attached to brand names depend on two key variables: the type of industry in which the brand operates; and the specific aspect of sustainability being communicated.

In terms of the sustainability message, research in the Journal of Business Ethics found consumers can be less interested when product functionality is key. Furthermore, a UK survey in 2022 found that about 15 per cent of consumers believed brands should support social causes, but nearly 60 per cent said they would rather see brand owners pay taxes and treat people fairly.

Among investors, too, “anti-purpose” and “anti-ESG” sentiment is growing. One (unnamed) leading bond fund manager even suggested to the FT that “ESG will be dead in five years”.

Media reports on the adverse impact of ESG controversies on investment are certainly now more frequent. For example, while Jope was still at the helm, the FT reported criticism of Unilever by influential fund manager Terry Smith for displaying sustainability credentials at the expense of managing the business.

Yet some executives feel under pressure to take a stand on environmental and social issues — in many cases believing they are morally obliged to do so or through a desire to improve their own reputations. This pressure may lead to a conflict with shareholders if sustainability becomes a promotional tool for managers, or for their personal social responsibility agenda, rather than creating business value .

Such opportunistic behaviours may lead to a perception that corporate sustainability policies are pursued only because of public image concerns.

Alison Taylor, at NYU Stern School of Business, recently described Unilever’s old materiality map — a visual representation of how companies assess which social and environmental factors matter most to them — to Sustainability magazine. She depicted it as an example of “baggy, vague, overambitious goals and self-aggrandising commitments that make little sense and falsely suggest a mayonnaise and soap company can solve intractable societal problems”.

In contrast, the “realism” approach of Schumacher is being promulgated as both more honest and more feasible. Former investment banker Alex Edmans, at London Business School, has coined the term “rational sustainability” to describe an approach that integrates financial principles into decision-making, and avoids using sustainability primarily for enhancing social image and reputation.

Such “rational sustainability” encompasses any business activity that creates long-term value — including product innovation, productivity enhancements, or corporate culture initiatives, regardless of whether they fall under the traditional ESG framework.

Similarly, Schumacher’s approach aims for fewer targets with greater impact, all while keeping financial objectives in sight.

Complex objectives, such as having a positive impact on the world, may be best achieved indirectly, as expounded by economist John Kay in his book, Obliquity . Schumacher’s “realistic sustainability” approach means focusing on long-term value creation, placing customers and investors to the fore. Saving the planet begins with meaningfully helping a company’s consumers and investors. Without their support, broader sustainability efforts risk failure.

Questions for discussion

Read: Unilever has ‘lost the plot’ by fixating on sustainability, says Terry Smith

Companies take step back from making climate target promises

The real impact of the ESG backlash

Unilever’s new chief says corporate purpose can be ‘unwelcome distraction ’

Unilever says new laxer environmental targets aim for ‘realism’

How should business executives incorporate ESG criteria in their commercial, investor, internal, and external communications? How can they strike a balance between purpose and profits?

How does purpose affect business and brand value? Under what circumstances or conditions can the impact of purpose be positive, neutral, or negative?

Are brands vehicles by which to drive social or environmental change? Is this the primary role of brands in the 21st century or do profits and clients’ needs come first?

Which categories or sectors might benefit most from strongly articulating and communicating a corporate purpose? Are there instances in which it might backfire?

In your opinion, is it necessary for brands to take a stance on social issues? Why or why not, and when?

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here .

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Promoted Content

Explore the series.

Follow the topics in this article

- Sustainability Add to myFT

- Impact investing Add to myFT

- Corporate governance Add to myFT

- Corporate social responsibility Add to myFT

- Business school case Add to myFT

Unilever Change Management Case Study

In today’s fast-paced business environment, change is inevitable.

Companies need to evolve and adapt to remain competitive, but managing change is not an easy task. Effective change management is crucial to the success of any organizational transformation, as it ensures that the changes are implemented smoothly and effectively.

In this blog post, we will examine a case study of change management at Unilever, one of the world’s largest consumer goods companies.

We will explore the challenges faced by Unilever, the change management approach it took, and the results of its initiatives.

Brief History and Growth of Unilever

Unilever is a British-Dutch multinational consumer goods company that was founded in 1929 through a merger between Dutch margarine producer Margarine Unie and British soap maker Lever Brothers.

Unilever has a long history of growth through mergers and acquisitions, with notable acquisitions including Bestfoods, Ben & Jerry’s, and Dollar Shave Club.

The company operates in over 190 countries and has a diverse portfolio of products, including food and beverages, cleaning agents, beauty and personal care products.

Unilever has also been committed to sustainability and social responsibility, and in 2010, it launched the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan, which aims to reduce the company’s environmental impact and improve the health and well-being of its customers.

Today, Unilever is one of the world’s largest consumer goods companies, with a revenue of over €50 billion in 2020.

External factors that led to organizational changes at Unilever

Unilever is a multinational consumer goods company that has undergone several organizational changes over the years. Here are three external factors that led to organizational changes at Unilever:

- Changing Consumer Preferences: The changing preferences and behaviors of consumers can have a significant impact on a company’s strategy and operations. For example, as more consumers started to prioritize eco-friendliness and sustainability, Unilever had to shift its focus towards more sustainable products and packaging. This led to the introduction of products like the “Dove Refillable Deodorant” and “Omo EcoActive” laundry detergent, as well as a commitment to reduce its plastic packaging by half by 2025.

- Competitive Pressure: Competition is another external factor that can force companies to make organizational changes. For example, when Unilever faced increasing competition from other consumer goods companies in emerging markets like India and China, it had to restructure its operations to be more efficient and cost-effective. This led to the consolidation of its global supply chain, as well as a greater emphasis on localizing its products and marketing strategies to better appeal to these markets.

- Technological Advancements: Advances in technology can also lead to organizational changes, as companies need to adapt to new ways of doing business. For example, as more consumers started to shop online, Unilever had to develop a strong e-commerce presence and optimize its digital marketing efforts. This led to the creation of Unilever Digital, a team dedicated to digital marketing and e-commerce, as well as a partnership with Alibaba to expand its online distribution in China.

Internal factors that led to organizational changes at Unilever

In addition to external factors, internal factors can also lead to organizational changes at Unilever. Here are three examples of internal factors that have led to organizational changes at the company:

- Management Changes: Changes in top management can often lead to organizational changes. For example, when Paul Polman became CEO of Unilever in 2009, he initiated a major restructuring of the company that aimed to streamline operations and focus on sustainable growth. This led to the consolidation of Unilever’s foods and personal care divisions, as well as a greater focus on emerging markets and sustainability.

- Financial Performance: Poor financial performance can also prompt organizational changes. For example, in 2017, Unilever reported slower-than-expected sales growth, leading the company to undertake a strategic review of its operations. This resulted in a decision to sell or spin off Unilever’s spreads business and focus on higher-growth areas like beauty and personal care.

- Organizational Culture: Organizational culture can also drive organizational change. For example, when Unilever identified a need to become more agile and innovative, it undertook a major cultural transformation initiative called “Connected 4 Growth.” This involved restructuring the company into smaller, more autonomous business units and giving employees greater freedom to experiment and take risks. The initiative aimed to foster a more entrepreneurial culture within the company and enable faster decision-making and innovation.

05 biggest steps taken by Unilever to implement changes

Unilever is a multinational consumer goods company that has undergone several organizational changes over the years. Here are the five biggest steps taken by Unilever to implement changes:

1. Sustainable Living Plan

In 2010, Unilever launched its Sustainable Living Plan, a comprehensive sustainability strategy that aimed to reduce the company’s environmental footprint, improve social impact, and drive profitable growth. The plan set ambitious targets for Unilever to achieve by 2020, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 50% and improving the livelihoods of millions of people in its supply chain. The Sustainable Living Plan has been a driving force behind many of Unilever’s organizational changes, such as the introduction of sustainable products and packaging and a greater emphasis on transparency and accountability.

2. Organizational Restructuring

Unilever has undertaken several major organizational restructuring initiatives over the years to streamline its operations and focus on high-growth areas. For example, in 2016, Unilever announced a plan to consolidate its foods and personal care businesses into a single division, with the goal of achieving greater efficiency and cost savings. Similarly, in 2017, Unilever announced a strategic review of its operations in response to slower-than-expected sales growth, resulting in a decision to sell or spin off its spreads business and focus on higher-growth areas like beauty and personal care.

3. Digital Transformation

As more consumers started to shop online, Unilever recognized the need to invest in its digital capabilities to stay competitive. In 2017, the company launched Unilever Digital, a team dedicated to digital marketing and e-commerce, and entered into a partnership with Alibaba to expand its online distribution in China. Unilever also invested in technology startups and acquired several digital companies to enhance its digital capabilities and drive innovation.

4. Cultural Transformation

Unilever recognized that its organizational culture needed to change to foster greater agility and innovation. In 2016, the company launched its “Connected 4 Growth” initiative, which involved restructuring the company into smaller, more autonomous business units and empowering employees to take more risks and experiment. The initiative aimed to create a more entrepreneurial culture within the company and enable faster decision-making and innovation.

5. Portfolio Transformation

Unilever has undergone several portfolio transformations over the years to focus on its core brands and divest non-core businesses. For example, in 2018, Unilever acquired the personal care and home care brands of Quala, a Latin American consumer goods company, to strengthen its presence in emerging markets. At the same time, the company divested its spreads business and announced plans to exit its tea business to focus on higher-growth areas. These portfolio transformations have helped Unilever to stay agile and adapt to changing market conditions.

05 Results of change management implemented at Unilever

The change management initiatives implemented at Unilever have had several positive outcomes and impacts. Here are some of the key examples:

- Increased Sustainability: The Sustainable Living Plan has been a key driver of Unilever’s sustainability efforts, and the company has made significant progress in reducing its environmental footprint and improving social impact. For example, by 2020, Unilever had achieved its target of sending zero non-hazardous waste to landfill from its factories, and had also reduced its greenhouse gas emissions by 46% per tonne of production.

- Improved Financial Performance: Unilever’s focus on portfolio transformation and strategic acquisitions has helped the company to improve its financial performance. For example, in 2020, the company reported a 1.9% increase in underlying sales growth and a 2.4% increase in operating profit margin.

- Enhanced Digital Capabilities: Unilever’s investments in digital transformation have enabled the company to stay competitive in a rapidly evolving digital landscape. For example, Unilever’s partnership with Alibaba has helped the company to expand its online distribution in China, while its investments in technology startups have helped to drive innovation and enhance its digital capabilities.

- Improved Organizational Agility: Unilever’s organizational restructuring and cultural transformation initiatives have helped to create a more agile and entrepreneurial company culture. This has enabled Unilever to make faster decisions and respond more quickly to changing market conditions.

- Increased Customer Satisfaction: Unilever’s focus on innovation and product development has resulted in the launch of several successful new products and brands, such as the plant-based meat alternative brand, The Vegetarian Butcher. These products have helped to increase customer satisfaction and drive growth for the company.

Final Words

Unilever’s successful implementation of change management is a testament to the company’s commitment to innovation, sustainability, and organizational excellence. By undertaking a variety of initiatives, such as the Sustainable Living Plan, organizational restructuring, digital transformation, cultural transformation, and portfolio transformation, Unilever has been able to adapt to changing market conditions and position itself for long-term success.

One key factor in Unilever’s success has been its ability to align its change management initiatives with its overall business strategy. By focusing on high-growth areas, investing in sustainability, and enhancing its digital capabilities, Unilever has been able to drive growth and improve profitability while also achieving its sustainability goals.

Another key factor has been Unilever’s emphasis on collaboration and stakeholder engagement. By working closely with suppliers, customers, and other stakeholders, Unilever has been able to create a shared sense of purpose and drive greater alignment around its sustainability and innovation goals.

About The Author

Tahir Abbas

Related posts.

Advantages of Diffusion of Innovation Theory

Advantages and Disadvantages of ERP

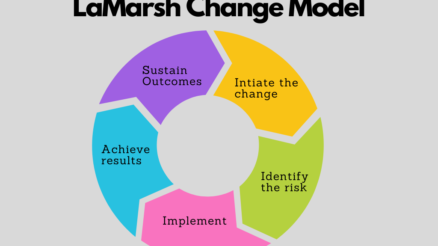

A Complete Guide to the LaMarsh Change Management Model

Reimagining the employee experience

Understanding the challenges.

Unilever asked us for a vision for its employees globally – a world-class experience which would be dynamic and personalized.

Unilever saw an opportunity to simplify the way employees found information through its many processes, systems and content resources. They realized that such a change would also free up support agents’ time to focus on higher value human interactions.

To understand how the employees felt, we asked them directly. We conducted a qualitative study of one-to-one interviews with employees of all levels, across different markets.

Co-designing the vision

Using this valuable insight, Accenture worked collaboratively with Unilever to co-design their vision, including a Rumble™ that generated ideas to explore and develop. Our long-standing relationship with Unilever brought a deep understanding of their business, which, coupled with our service design approach, enabled the co-creation of a groundbreaking, real vision built on what mattered most to Unilever’s employees.

Unilever had articulated three core pillars that would inspire their new employee experience: human experiences, simple interactions, meaningful impact.

The “Employee Universe” was created to enable the vision, which comprised a matrix of interconnected components, fronted by a chatbot named Una. We created Una’s personality, and designed her human-like conversation to reinforce Unilever’s brand and values. Una becomes a personal assistant, guiding the employee to what they need in that moment. Her conversations were contextually relevant, and continuously improved through a built-in learning loop.

Test, learn and iterate

We ran a “Living Lab”, whereby we would rapidly test, assess and fine-tune throughout to ensure we maximized Una’s impact. We delivered a Proof of Value to demonstrate how new hires would feel about using AI chatbot technology to answer day-to-day queries and test and iterate the underpinning technology.

Employees who tested the pilot enjoyed their initial experience of using Una, giving her a rating of 4.6/5, and 85% employee satisfaction. Our vision and chatbot, plus Living Lab, became the foundation for a broader program of transforming the employee experience at Unilever.

MORE CASE STUDIES

Marriott international.

Travel innovation

First-class ticket to tomorrow

Auris Health

Revolutionizing endoscopy

Connect with us

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

- April 2020 (Revised October 2020)

- HBS Case Collection

Unilever's Response to the Future of Work

- Format: Print

- | Language: English

- | Pages: 18

About The Author

William R. Kerr

Related work.

- November 2020

- Faculty Research

- Unilever's Response to the Future of Work By: William R. Kerr and Bailey McAfee

- Unilever's Response to the Future of Work By: William R. Kerr, Emilie Billaud and Mette Fuglsang Hjortshoej

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The discussion draws on a case study of the Anglo-Dutch consumer goods manufacturer Unilever, which has been one of the largest direct investors in the United States in the twentieth century.

Launched in 2016, Unilever’s Future of Work initiative aimed to accelerate the speed of change throughout the organization and prepare its workforce for a digitalized and highly automated era.

Business school teaching case study: Unilever chief signals rethink on ESG. Why is the consumer goods group backpedalling on responsible-business targets? Explore the issues with this...

Unilever Human Rights Case Study Collaborating to improve working conditions for waste pickers September 2024 Packaging plays an important role in bringing Unilever brands into the hands of our consumers around the world. An estimated 60% of all plastic that is recycled globally is collected by waste pickers working on an informal basis. Waste ...

Abstract and Figures. Learn how Unilever uses IT technical opportunities to innovate. Starting with business strategy and deriving the IT strategy, this case gives concrete examples for...

In this blog post, we will examine a case study of change management at Unilever, one of the world’s largest consumer goods companies. We will explore the challenges faced by Unilever, the change management approach it took, and the results of its initiatives.

Unilever asked us for a vision for its employees globally – a world-class experience which would be dynamic and personalized. Unilever saw an opportunity to simplify the way employees found information through its many processes, systems and content resources.

Published Mar 8, 2024. In today's competitive landscape, companies are increasingly recognizing the value of aligning business strategies with environmental and social responsibility. Unilever, a...

Explore Unilever's sustainability efforts amid rising global emissions. Discover its strides in tackling plastic waste, healthier foods & governance challenges.

Launched in 2016, Unilever’s Future of Work initiative aimed to accelerate the speed of change throughout the organization and prepare the workforce for a digitalized and highly automated era.