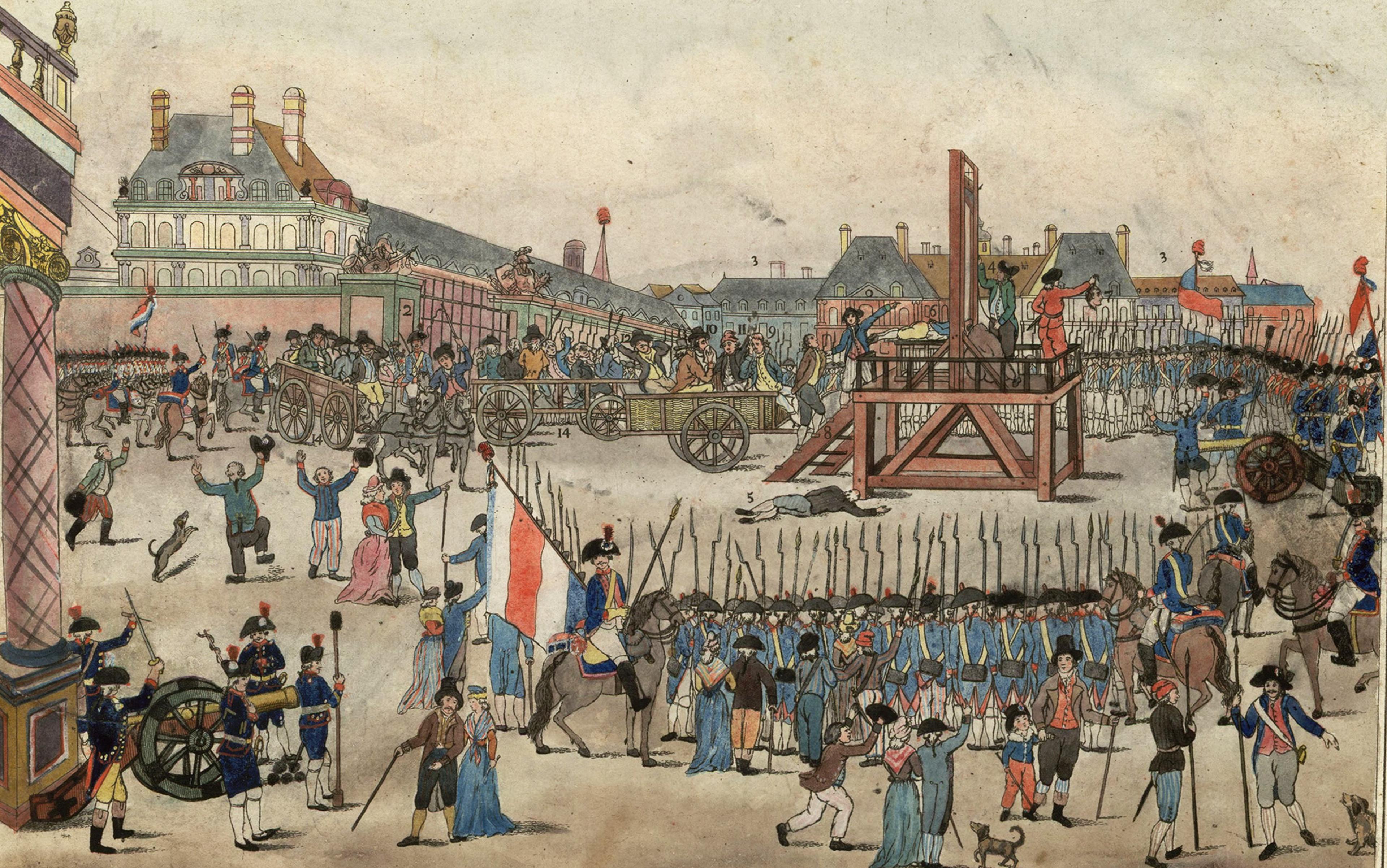

The execution of Robespierre and his accomplices, 17 July 1794 (10 Thermidor Year II). Robespierre is depicted holding a handkerchief and dressed in a brown jacket in the cart immediately to the left of the scaffold. Photo courtesy the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

Vive la révolution!

Must radical political change generate uncontainable violence the french revolution is both a cautionary and inspiring tale.

by Jeremy Popkin + BIO

If the French Revolution of 1789 was such an important event, visitors to France’s capital city of Paris often wonder, why can’t they find any trace of the Bastille, the medieval fortress whose storming on 14 July 1789 was the revolution’s most dramatic moment? Determined to destroy what they saw as a symbol of tyranny, the ‘victors of the Bastille’ immediately began demolishing the structure. Even the column in the middle of the busy Place de la Bastille isn’t connected to 1789: it commemorates those who died in another uprising a generation later, the ‘July Revolution’ of 1830.

The legacy of the French Revolution is not found in physical monuments, but in the ideals of liberty, equality and justice that still inspire modern democracies. More ambitious than the American revolutionaries of 1776, the French in 1789 were not just fighting for their own national independence: they wanted to establish principles that would lay the basis for freedom for human beings everywhere. The United States Declaration of Independence briefly mentioned rights to ‘liberty, equality, and the pursuit of happiness’, without explaining what they meant or how they were to be realised. The French ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen’ spelled out the rights that comprised liberty and equality and outlined a system of participatory government that would empower citizens to protect their own rights.

Much more openly than the Americans, the French revolutionaries recognised that the principles of liberty and equality they had articulated posed fundamental questions about such issues as the status of women and the justification of slavery. In France, unlike the US, these questions were debated heatedly and openly. Initially, the revolutionaries decided that ‘nature’ denied women political rights and that ‘imperious necessity’ dictated the maintenance of slavery in France’s overseas colonies, whose 800,000 enslaved labourers outnumbered the 670,000 in the 13 American states in 1789.

As the revolution proceeded, however, its legislators took more radical steps. A law redefining marriage and legalising divorce in 1792 granted women equal rights to sue for separation and child custody; by that time, women had formed their own political clubs, some were openly serving in the French army, and Olympe de Gouges’s eloquent ‘Declaration of the Rights of Woman’ had insisted that they should be allowed to vote and hold office. Women achieved so much influence in the streets of revolutionary Paris that they drove male legislators to try to outlaw their activities. At almost the same time, in 1794, faced with a massive uprising among the enslaved blacks in France’s most valuable Caribbean colony, Saint-Domingue, the French National Convention abolished slavery and made its former victims full citizens. Black men were seated as deputies to the French legislature and, by 1796, the black general Toussaint Louverture was the official commander-in-chief of French forces in Saint-Domingue, which would become the independent nation of Haiti in 1804.

The French Revolution’s initiatives concerning women’s rights and slavery are just two examples of how the French revolutionaries experimented with radical new ideas about the meaning of liberty and equality that are still relevant. But the French Revolution is not just important today because it took such radical steps to broaden the definitions of liberty and equality. The movement that began in 1789 also showed the dangers inherent in trying to remake an entire society overnight. The French revolutionaries were the first to grant the right to vote to all adult men, but they were also the first to grapple with democracy’s shadow side, demagogic populism, and with the effects of an explosion of ‘new media’ that transformed political communication. The revolution saw the first full-scale attempt to impose secular ideas in the face of vocal opposition from citizens who proclaimed themselves defenders of religion. In 1792, revolutionary France became the first democracy to launch a war to spread its values. A major consequence of that war was the creation of the first modern totalitarian dictatorship, the rule of the Committee of Public Safety during the Reign of Terror. Five years after the end of the Terror, Napoleon Bonaparte, who had gained fame as a result of the war, led the first modern coup d’état , justifying it, like so many strongmen since, by claiming that only an authoritarian regime could guarantee social order.

The fact that Napoleon reversed the revolutionaries’ expansion of women’s rights and reintroduced slavery in the French colonies reminds us that he, like so many of his imitators in the past two centuries, defined ‘social order’ as a rejection of any expansive definition of liberty and equality. Napoleon also abolished meaningful elections, ended freedom of the press, and restored the public status of the Catholic Church. Determined to keep and even expand the revolutionaries’ foreign conquests, he continued the war that they had begun, but French armies now fought to create an empire, dropping any pretence of bringing freedom to other peoples.

T he relevance of the French Revolution to present-day debates is the reason why I decided to write A New World Begins: The History of the French Revolution (2020), the first comprehensive English-language account of that event for general readers in more than 30 years. Having spent my career researching and teaching the history of the French Revolution, however, I know very well that it was more than an idealistic crusade for human rights. If the fall of the Bastille remains an indelible symbol of aspirations for freedom, the other universally recognised symbol of the French Revolution, the guillotine, reminds us that the movement was also marked by violence. The American Founding Fathers whose refusal to consider granting rights to women or ending slavery we now rightly question did have the good sense not to let their differences turn into murderous feuds; none of them had to reflect, as the French legislator Pierre Vergniaud did on the eve of his execution, that their movement, ‘like Saturn, is devouring its own children’.

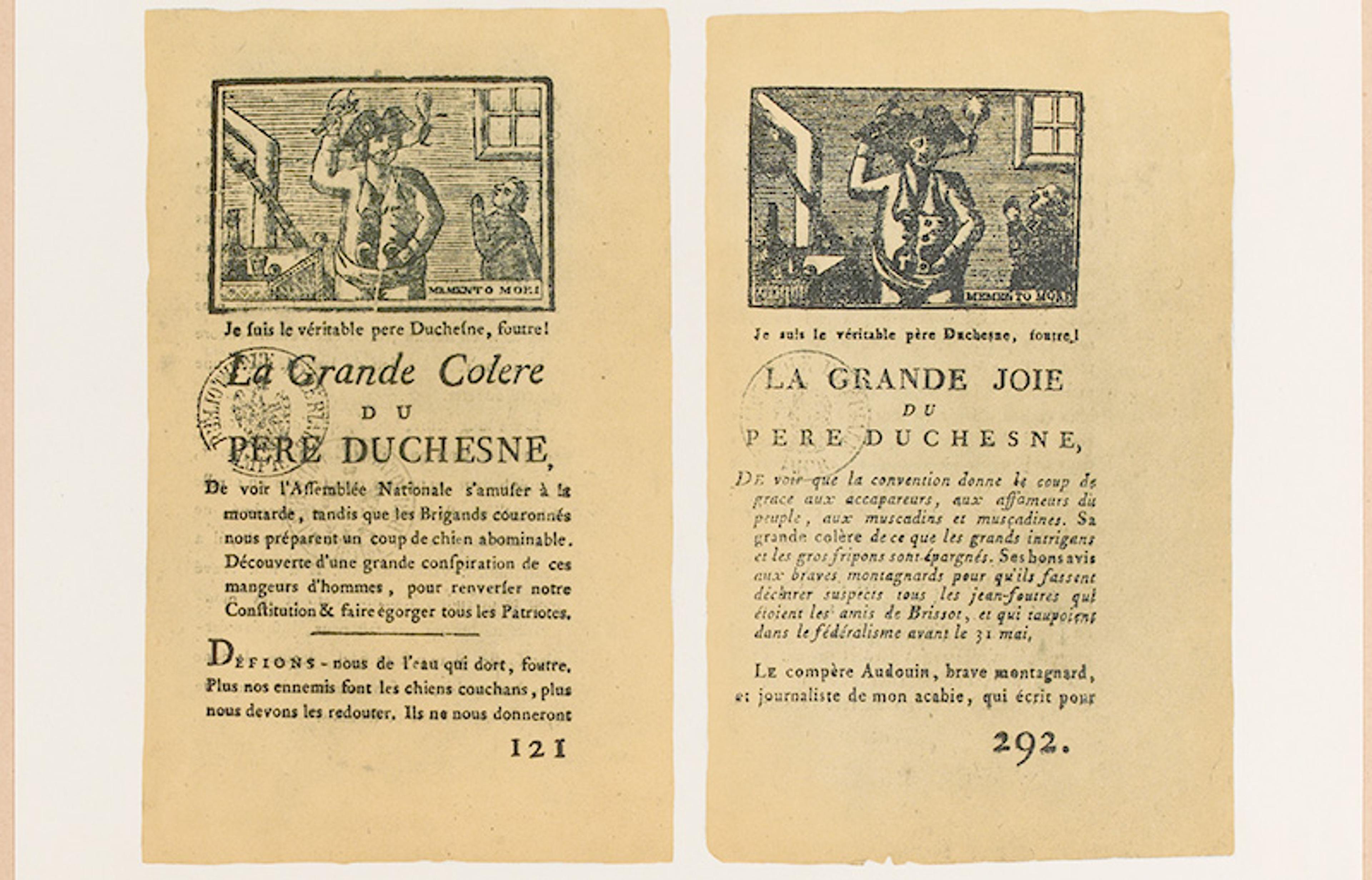

It is hard to avoid concluding that there was a relationship between the radicalism of the ideas that surfaced during the French Revolution and the violence that marked the movement. In my book, I introduce readers to a character, the ‘Père Duchêne’, who came to represent the populist impulses of the revolution. Nowadays, we would call the Père Duchêne a meme. He was not a real person: instead, he was a character familiar to audiences in Paris’s popular theatres, where he functioned as a representative of the country’s ordinary people. Once the revolution began, a number of journalists began publishing pamphlets supposedly written by the Père Duchêne, in which they demanded that the National Assembly do more to benefit the poor. The small newspapers that used his name carried a crude woodcut on their front page showing the Père Duchêne in rough workers’ clothing. Holding a hatchet over his head, with two pistols stuck in his belt and a musket at his side, the Père Duchêne was a visual symbol of the association between the revolution and popular violence.

The elites had enriched themselves at the expense of the people, and needed to be forced to share their power

Although his crude language and his constant threat to resort to violence alienated the more moderate revolutionaries, the Père Duchêne was the living embodiment of one of the basic principles incorporated in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. The sixth article of that document affirmed that ‘the law is the expression of the general will’ and promised that ‘all citizens have the right to participate personally, or through their representatives, in its establishment’. The fictitious Père Duchêne’s message to readers, no matter how poor and uneducated they might be, was that an ordinary person could claim a voice in politics.

The Great Anger and The Great Joy of Père Duchêne, Hébert’s radical and rabble-rousing pamphlet. Courtesy Musée Carnavalet, Paris

Like present-day populists, the Père Duchêne had a simple political programme. The elites who ruled France before 1789 had enriched themselves at the expense of the people. They needed to be forced to share their power and wealth. When the revolution did not immediately improve the lives of the masses, the Père Duchêne blamed the movement’s more moderate leaders, accusing them of exploiting it for their own benefit. The journalists who wrote under the name of the Père Duchêne used colourful language laced with obscenities; they insisted that their vulgarity showed that they were ‘telling it like it is’. Their tone was vindictive and vengeful; they wanted to see their targets humiliated and, in many cases, sent to the guillotine. The most successful Père Duchêne journalist, Jacques-René Hébert, built a political career through his success in using the media. At the height of the Reign of Terror, he pushed through the creation of a ‘revolutionary army’ controlled by his friends to intimidate enemies of the revolution, and seemed on the verge of taking over the government.

Maximilien Robespierre and his more middle-class colleagues on the Committee of Public Safety feared that Hébert’s populist movement might drive them from power. They decided that they had no choice but to confront Hébert and his followers, even if it meant alienating the ‘base’ of ordinary Paris residents, the famous sans-culottes . Using the same smear tactics that the Père Duchêne had perfected, they accused Hébert of dubious intrigues with foreigners and other questionable activities. Like many bullies, Hébert quickly collapsed when he found himself up against serious opponents determined to fight back; the crowd that cheered his dispatch to the guillotine in March 1794 was larger than for many of the executions that he had incited. But he and the other Père Duchênes, as well as their female counterparts, the Mère Duchênes who flourished at some points in the revolution, had done much to turn the movement from a high-minded crusade for human rights into a free-for-all in which only the loudest voices could make themselves heard.

T he ambivalent legacy of the French Revolution’s democratic impulse, so vividly brought to life in the figure of the Père Duchêne, underlines the way in which the movement begun in 1789 remains both an inspiration and a warning for us today. In the more than 200 years since the storming of the Bastille, no one has formulated the human yearning for freedom and justice more eloquently than the French revolutionaries, and no one has shown more clearly the dangers that a one-sided pursuit of those goals can create. The career of the most famous of the radical French revolutionaries, Robespierre, is the most striking demonstration of that fact.

Robespierre is remembered because he was the most eloquent defender of the dictatorship created during the revolution’s most radical period, the months known as the Reign of Terror. Robespierre’s speech on the principles of revolutionary government, delivered on 25 December 1793, made an uncompromising case for the legitimacy of extreme measures to defeat those he called ‘the enemies of liberty’. Paradoxically, he insisted, the only way to create a society in which citizens could exercise the individual freedoms promised in the Declaration of Rights was to suspend those rights until the revolution’s opponents were conclusively defeated.

Robespierre’s colleagues on the all-powerful Committee of Public Safety chose him to defend their policies because he was more than just a spokesman for harsh measures against their opponents. From the time he first appeared on the scene as one of the 1,200 deputies to the Estates General summoned by Louis XVI in May 1789, his fellow legislators recognised the young provincial lawyer’s intelligence and his unswerving commitment to the ideals of democracy. The renegade aristocrat the comte de Mirabeau, the most prominent spokesman of the revolutionary ‘patriots’ in 1789 but an often cynical pragmatist, quickly sized up his colleague: ‘That man will go far, because he believes everything he says.’ Unlike the Père Duchêne, Robespierre always dressed carefully and spoke in pure, educated French. Other revolutionary leaders, like the rabblerousing orator Georges Danton, were happy to join insurrectionary crowds in the streets; Robespierre never personally took part in any of the French Revolution’s explosions of violence. Yet no one remains more associated with the violence of the Reign of Terror than Robespierre.

To reduce Robespierre’s legacy to his association with the Terror is to overlook the importance of his role as a one of history’s most articulate proponents of political democracy. When the majority of the deputies in France’s revolutionary National Assembly tried to restrict full political rights to the wealthier male members of the population, Robespierre reminded them of the Declaration of Rights’ assertion that freedom meant the right to have a voice in making the laws that citizens had to obey. ‘Is the law the expression of the general will, when the greater number of those for whom it is made cannot contribute to its formation?’ he asked. Long before our present-day debates about income inequality, he denounced a system that put real political power in the hands of the wealthy: ‘And what an aristocracy! The most unbearable of all, that of the rich.’ In the early years of the revolution, Robespierre firmly defended freedom of the press and called for the abolition of the death penalty. When white colonists insisted that France could not survive economically without slavery, Robespierre cried out: ‘Perish the colonies rather than abandon a principle!’

The majority of the population was not ready to embrace a radical secularist movement

Explaining how Robespierre, the principled defender of liberty and equality, became in just a few short years the leading advocate of a system of revolutionary government that foreshadowed the 20th century’s totalitarian dictatorships is perhaps the greatest challenge in defending the legacy of the French Revolution. Robespierre was no innocent, and in the last months of his short political career – he was only 36 when he died – his clumsy confrontations with his colleagues made him a dangerous number of enemies. Unlike the Père Duchêne, however, Robespierre never embraced violence as an end in itself, and a close examination of his career shows that he was often trying to find ways to limit the damage caused by policies he had not originally endorsed. In 1792, when most of his fellow Jacobin radicals embraced the call for a revolutionary war to ensure France’s security by toppling the hostile monarchies surrounding it, Robespierre warned against the illusion that other peoples would turn against their own governments to support the French. ‘No one loves armed missionaries,’ he insisted, a warning that recent US leaders might have done well to heed.

When radicals such as Hébert started a campaign to ‘de-Christianise’ France, in order to silence opposition to the movement’s effort to reform the Catholic Church and sell off its property for the benefit of the revolution, Robespierre reined them in. He recognised that the majority of the population was not ready to embrace a radical secularist movement bent on turning churches into ‘temples of reason’ and putting up signs in cemeteries calling death ‘an eternal sleep’. Robespierre proposed instead the introduction of a purified and simplified ‘cult of the Supreme Being’, which he thought believers could embrace without abandoning their faith in a higher power and their belief in the immortality of the soul.

To inaugurate the new state religion, Robespierre declared 8 June 1794 (20 Prairial Year II) to be the Festival of the Supreme Being. The festival was organised by the artist Jacques-Louis David and took place around a man-made mountain on the Champ de Mars. Courtesy Musée Carnavalet, Paris

Robespierre knew that many of the revolution’s bitterest opponents were motivated by loyalty to the Catholic Church. The revolution had not begun as an anti-religious movement. Under the rules used in the elections to what became the French National Assembly in 1789, a fourth of all the deputies were clergy from the Catholic Church, an institution so woven into the fabric of the population’s life that hardly anyone could imagine its disappearance. Criticism that the Church had grown too wealthy and that many of its beliefs failed to measure up to the standards of reason promoted by the Enlightenment was widespread, even among priests, but most hoped to see religion, like every other aspect of French life, ‘regenerated’ by the impulses of the revolution, not destroyed.

The revolutionaries’ confrontation with the Church began, not with an argument about beliefs, but because of the urgent need to meet the crisis in government revenues that had forced king Louis XVI to summon a national assembly in the first place. Determined to avoid a chaotic public bankruptcy, and reluctant to raise taxes on the population, the legislators decided, four months after the storming of the Bastille, to put the vast property of the Catholic Church ‘at the disposition of the nation’. Many Catholic clergy, especially underpaid parish priests who resented the luxury in which their aristocratic bishops lived, supported the expropriation of Church property and the idea that the government, which now took over the responsibility for funding the institution, had the right to reform it. Others, however, saw the reform of the Church as a cover for an Enlightenment-inspired campaign against their faith, and much of the lay population supported them. In one region of France, peasants formed a ‘Catholic and Royal Army’ and revolted against the revolution that had supposedly been carried out for their benefit. Women, who found in the cult of Mary and female saints a source of psychological support, were often in the forefront of this religiously inspired resistance to the revolution.

To supporters of the revolution, this religious opposition to their movement looked like a nationwide conspiracy preventing progress. The increasingly harsh measures taken to quell resistance to Church reform prefigured the policies of the Reign of Terror. The plunge into war in the spring of 1792, justified in part to show domestic opponents of the revolution that they could not hope for any support from abroad, allowed the revolutionaries to define the disruptions caused by diehard Catholics as forms of treason. Suspicions that Louis XVI, who had accepted the demand for a declaration of war, and his wife Marie-Antoinette were secretly hoping for a quick French defeat that would allow foreign armies to restore their powers led to their imprisonment and execution.

A ccusations of foreign meddling in revolutionary politics, a so-called foreign plot that supposedly involved the payment of large sums of money to leading deputies to promote special interests and undermine French democracy, were another source of the fears that fuelled the Reign of Terror. Awash in a sea of ‘fake news’, political leaders and ordinary citizens lost any sense of perspective, and became increasingly ready to believe even the most far-fetched accusations. Robespierre, whose personal honesty had earned him the nickname ‘The Incorruptible’, was particularly quick to suspect any of his colleagues who seemed ready to tolerate those who enriched themselves from the revolution or had contacts with foreigners. Rather than any lust for power, it was Robespierre’s weakness for seeing any disagreement with him as a sign of corruption that led him to support the elimination of numerous other revolutionary leaders, including figures, such as Danton, who had once been his close allies. Other, more cynical politicians joined Robespierre in expanding the Reign of Terror, calculating that their own best chance of survival was to strike down their rivals before they themselves could be targeted.

Although the toxic politics of its most radical phase did much to discredit the revolution, the ‘Reign of Terror’, which lasted little more than one year out of 10 between the storming of the Bastille and Napoleon’s coup d’état , was also a time of important experiments in democracy. While thousands of ordinary French men and women found themselves unjustly imprisoned during the Terror, thousands of others – admittedly, only men – held public office for the first time. The same revolutionary legislature that backed Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety took the first steps toward creating a modern national welfare system and passed plans for a comprehensive system of public education. Revolutionary France became the first country to create a system of universal military conscription and to promise ordinary soldiers that, if they proved themselves on the battlefield, there was no rank to which they could not aspire. The idea that society needed a privileged leadership class in order to function was challenged as never before.

Among the men from modest backgrounds who rose to positions they could never have attained before 1789 was a young artillery officer whose strong Corsican accent marked him as a provincial: Napoleon. A mere lieutenant when the Bastille was stormed, he was promoted to general just four years later, after impressing Robespierre’s brother Augustin with his skill in defeating a British invasion force on France’s southern coast. Five years after the overthrow of Robespierre on 27 July 1794 – or 9 Thermidor Year II, according to the new calendar that the revolutionaries had adopted to underline their total break with the past – Napoleon joined with a number of revolutionary politicians to overthrow the republican regime that had come out of the revolution and replace it with what soon became a system of one-man rule. Napoleon’s seizure of power has been cited ever since as evidence that the French Revolution, unlike the American, was essentially a failure. The French revolutionaries, it is often said, had tried to make too many changes too quickly, and the movement’s violence had alienated too much of the population to allow it to succeed.

To accept this verdict on the French Revolution is to ignore a crucial but little-known aspect of its legacy: the way in which the movement’s own leaders, determined to escape from the destructive politics of the Reign of Terror after Robespierre’s death, worked to ‘exit from the Terror’, as one historian has put it, and create a stable form of constitutional government. The years that history books call the period of the ‘Thermidorian reaction’ and the period of the Directory, from July 1794 to November 1799, comprise half of the decade of the French Revolution. They provide an instructive lesson in how a society can try to put itself back on an even keel after an experience during which all the ordinary rules of politics have been broken.

The post-Robespierre republic was brought down by the disloyalty of its own political elite

One simple lesson from the post-Terror years of the revolution that many subsequent politicians have learned is to blame all mistakes on one person. In death, Robespierre was built up into a ‘tiger thirsty for blood’ who had supposedly wanted to make himself a dictator or even king. All too aware that, in reality, thousands of others had helped to make the revolutionary government function, however, Robespierre’s successors found themselves under pressure to bring at least some of the Terror’s other leaders to justice. At times, the process escaped from control, as when angry crowds massacred political prisoners in cities in the south during a ‘white terror’ in 1795. On the whole, however, the republican leaders after 1794 succeeded in convincing the population that the excesses of the Terror would not be repeated, even if some of the men in power had been as deeply implicated in those excesses as Robespierre.

For five years after Robespierre’s execution, France lived under a quasi-constitutional system, in which laws were debated by a bicameral legislature and discussed in a relatively free press. On several occasions, it is true, the Directory, the five-man governing council, ‘corrected’ the election results to ensure its own hold on power, undermining the authority of the constitution, but the mass arrests and arbitrary trials that had marked the Reign of Terror were not repeated. The Directory’s policies enabled the country’s economy to recover after the disorder of the revolutionary years. Harsh toward the poor who had identified themselves with the Père Duchêne, it consolidated the educational reforms started during the Terror. Napoleon would build on the Directory’s success in establishing a modern, centralised system of administration. He himself was one of the many military leaders who enabled France to defeat its continental enemies and force them to recognise its territorial gains.

Although legislative debates in this period reflected a swing against the expanded rights granted to women earlier in the revolution, the laws passed earlier were not repealed. Despite a heated campaign waged by displaced plantation-owners, the thermidorians and the Directory maintained the rights granted to the freed blacks in the French colonies. Black men from Saint-Domingue and Guadeloupe were elected as deputies and took part in parliamentary debates. In Saint-Domingue, the black general Louverture commanded French forces that defeated a British invasion; by 1798, he had been named the governor of the colony. His power was so great that the American government, by this time locked in a ‘quasi-war’ with France, negotiated directly with him, hoping to bring pressure on Paris to end the harassment of American merchant ships in the Caribbean.

The post-Robespierre French republic was brought down, more than anything else, by the disloyalty of its own political elite. Even before Napoleon unexpectedly returned from the expedition to Egypt on which he had been dispatched in mid-1798, many of the regime’s key figures had decided that the constitution they themselves had helped to draft after Robespierre’s fall provided too many opportunities for rivals to challenge them. What Napoleon found in the fall of 1799 was not a country on the verge of chaos but a crowd of politicians competing with each other to plan coups to make their positions permanent. He was able to choose the allies who struck him as most likely to serve his purposes, knowing that none of them had the popularity or the charisma to hold their own against him once the Directory had been overthrown.

One cannot simply conclude, then, that the history of the French Revolution proves that radical attempts to change society are doomed to failure, or that Napoleon’s dictatorship was the inevitable destination at which the revolution was doomed to arrive. But neither can one simply hail the French movement as a forerunner of modern ideas about liberty and equality. In their pursuit of those goals, the French revolutionaries discovered how vehemently some people – not just privileged elites but also many ordinary men and women – could resist those ideas, and how dangerous the impatience of their own supporters could become. Robespierre’s justification of dictatorial methods to overcome the resistance to the revolution had a certain logic behind it, but it opened the door to many abuses.

Despite all its violence and contradictions, however, the French Revolution remains meaningful for us today. To ignore or reject the legacy of its calls for liberty and equality amounts to legitimising authoritarian ideologies or arguments for the inherent inequality of certain groups of people. If we want to live in a world characterised by respect for fundamental individual rights, we need to learn the lessons, both positive and negative, of the great effort to promote those ideals that tore down the Bastille in 1789.

The cochlear question

As the hearing parent of a deaf baby, I’m confronted with an agonising decision: should I give her an implant to help her hear?

Abi Stephenson

Food and drink

The flavour of mechanisation

Olive oil was revered and cherished by the ancients. But its distinctive peppery taste is really a modern invention

Massimo Mazzotti

Nations and empires

Utopia brasileira

Within less than a decade, Brazil will have as many evangelicals as Catholics, a transcendence born of the prosperity gospel

Alex Hochuli

Colonies of former colonies

India’s ongoing subjugation of Kashmir holds portentous lessons about the nature of contemporary colonialism

Hafsa Kanjwal

History of ideas

Settling accounts

Before he was famous, Jean-Jacques Rousseau was Louise Dupin’s scribe. It’s her ideas on inequality that fill his writings

Rebecca Wilkin

Philosophy of mind

Rage against the machine

For all the promise and dangers of AI, computers plainly can’t think. To think is to resist – something no machine does

History Cooperative

French Revolution: History, Timeline, Causes, and Outcomes

The French Revolution, a seismic event that reshaped the contours of political power and societal norms, began in 1789, not merely as a chapter in history but as a dramatic upheaval that would influence the course of human events far beyond its own time and borders.

It was more than a clash of ideologies; it was a profound transformation that questioned the very foundations of monarchical rule and aristocratic privilege, leading to the rise of republicanism and the concept of citizenship.

The causes of this revolution were as complex as its outcomes were far-reaching, stemming from a confluence of economic strife, social inequalities, and a hunger for political reform.

The outcomes of the French Revolution, embedded in the realms of political thought, civil rights, and societal structures, continue to resonate, offering invaluable insights into the power and potential of collective action for change.

Table of Contents

Time and Location

The French Revolution, a cornerstone event in the annals of history, ignited in 1789, a time when Europe was dominated by monarchical rule and the vestiges of feudalism. This epochal period, which spanned a decade until the late 1790s, witnessed profound social, political, and economic transformations that not only reshaped France but also sent shockwaves across the continent and beyond.

Paris, the heart of France, served as the epicenter of revolutionary activity , where iconic events such as the storming of the Bastille became symbols of the struggle for freedom. Yet, the revolution was not confined to the city’s limits; its influence permeated through every corner of France, from bustling urban centers to serene rural areas, each witnessing the unfolding drama of revolution in unique ways.

The revolution consisted of many complex factions, each representing a distinct set of interests and ideologies. Initially, the conflict arose between the Third Estate, which included a diverse group from peasants and urban laborers to the bourgeoisie, and the First and Second Estates, made up of the clergy and the nobility, respectively.

The Third Estate sought to dismantle the archaic social structure that relegated them to the burden of taxation while denying them political representation and rights. Their demands for reform and equality found resonance across a society strained by economic distress and the autocratic rule of the monarchy.

As the revolution evolved, so too did the nature of the conflict. The initial unity within the Third Estate fractured, giving rise to factions such as the Jacobins and Girondins, who, despite sharing a common revolutionary zeal, diverged sharply in their visions for France’s future.

The Jacobins , with figures like Maximilien Robespierre at the helm, advocated for radical measures, including the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic, while the Girondins favored a more moderate approach.

The sans-culottes , representing the militant working-class Parisians, further complicated the revolutionary landscape with their demands for immediate economic relief and political reforms.

The revolution’s adversaries were not limited to internal factions; monarchies throughout Europe viewed the republic with suspicion and hostility. Fearing the spread of revolutionary fervor within their own borders, European powers such as Austria, Prussia, and Britain engaged in military confrontations with France, aiming to restore the French monarchy and stem the tide of revolution.

These external threats intensified the internal strife, fueling the revolution’s radical phase and propelling it towards its eventual conclusion with the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, who capitalized on the chaos to establish his own rule.

READ MORE: How Did Napoleon Die: Stomach Cancer, Poison, or Something Else?

Causes of the French Revolution

The French Revolution’s roots are deeply embedded in a confluence of political, social, economic, and intellectual factors that, over time, eroded the foundations of the Ancien Régime and set the stage for revolutionary change.

At the heart of the revolution were grievances that transcended class boundaries, uniting much of the nation in a quest for profound transformation.

Economic Hardship and Social Inequality

A critical catalyst for the revolution was France’s dire economic condition. Fiscal mismanagement, costly involvement in foreign wars (notably the American Revolutionary War), and an antiquated tax system placed an unbearable strain on the populace, particularly the Third Estate, which bore the brunt of taxation while being denied equitable representation.

Simultaneously, extravagant spending by Louis XVI and his predecessors further drained the national treasury, exacerbating the financial crisis.

The social structure of France, rigidly divided into three estates, underscored profound inequalities. The First (clergy) and Second (nobility) Estates enjoyed significant privileges, including exemption from many taxes, which contrasted starkly with the hardships faced by the Third Estate, comprising peasants , urban workers, and a rising bourgeoisie.

This disparity fueled resentment and a growing demand for social and economic justice.

Enlightenment Ideals

The Enlightenment , a powerful intellectual movement sweeping through Europe, profoundly influenced the revolutionary spirit. Philosophers such as Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu criticized traditional structures of power and authority, advocating for principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Their writings inspired a new way of thinking about governance, society, and the rights of individuals, sowing the seeds of revolution among a populace eager for change.

Political Crisis and the Estates-General

The immediate catalyst for the French Revolution was deeply rooted in a political crisis, underscored by the French monarchy’s chronic financial woes. King Louis XVI, facing dire fiscal insolvency, sought to break the deadlock through the convocation of the Estates-General in 1789, marking the first assembly of its kind since 1614.

READ MORE: French Royal Family Tree: The Lineage of French Monarchs

This critical move, intended to garner support for financial reforms, unwittingly set the stage for widespread political upheaval. It provided the Third Estate, representing the common people of France, with an unprecedented opportunity to voice their longstanding grievances and demand a more significant share of political authority.

The Third Estate, comprising a vast majority of the population but long marginalized in the political framework of the Ancien Régime, seized this moment to assert its power. Their transformation into the National Assembly was a monumental shift, symbolizing a rejection of the existing social and political order.

The catalyst for this transformation was their exclusion from the Estates-General meeting, leading them to gather in a nearby tennis court. There, they took the historic Tennis Court Oath, vowing not to disperse until France had a new constitution.

This act of defiance was not just a political statement but a clear indication of the revolutionaries’ resolve to overhaul French society.

Amidst this burgeoning crisis, the personal life of Marie Antoinette , Louis XVI’s queen, became a focal point of public scrutiny and scandal.

Married to Louis at the tender age of fourteen, Marie Antoinette, the youngest daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Francis I, was known for her lavish lifestyle and the preferential treatment she accorded her friends and relatives.

READ MORE: Roman Emperors in Order: The Complete List from Caesar to the Fall of Rome

Her disregard for traditional court fashion and etiquette, along with her perceived extravagance, made her an easy target for public criticism and ridicule. Popular songs in Parisian cafés and a flourishing genre of pornographic literature vilified the queen, accusing her of infidelity, corruption, and disloyalty.

Such depictions, whether grounded in truth or fabricated, fueled the growing discontent among the populace, further complicating the already tense political atmosphere.

The intertwining of personal scandals with the broader political crisis highlighted the deep-seated issues within the French monarchy and aristocracy, contributing to the revolutionary fervor.

As the political crisis deepened, the actions of the Third Estate and the controversies surrounding Marie Antoinette exemplified the widespread desire for change and the rejection of the Ancient Régime’s corruption and excesses.

Key Concepts, Events, and People of the French Revolution

As the Estates General convened in 1789, little did the world know that this gathering would mark the beginning of a revolution that would forever alter the course of history.

Through the rise and fall of factions, the clash of ideologies, and the leadership of remarkable individuals, this era reshaped not only France but also set a precedent for future generations.

From the storming of the Bastille to the establishment of the Directory, each event and figure played a crucial role in crafting a new vision of governance and social equality.

Estates General

When the Estates General was summoned in May 1789, it marked the beginning of a series of events that would catalyze the French Revolution. Initially intended as a means for King Louis XVI to address the financial crisis by securing support for tax reforms, the assembly instead became a flashpoint for broader grievances.

Representing the three estates of French society—the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners—the Estates General highlighted the profound disparities and simmering tensions between these groups.

The Third Estate, comprising 98% of the population but traditionally having the least power, seized the moment to push for more significant reforms, challenging the very foundations of the Ancient Régime.

The deadlock over voting procedures—where the Third Estate demanded votes be counted by head rather than by estate—led to its members declaring themselves the National Assembly, an act of defiance that effectively inaugurated the revolution.

This bold step, coupled with the subsequent Tennis Court Oath where they vowed not to disperse until a new constitution was created, underscored a fundamental shift in authority from the monarchy to the people, setting a precedent for popular sovereignty that would resonate throughout the revolution.

Rise of the Third Estate

The Rise of the Third Estate underscores the growing power and assertiveness of the common people of France. Fueled by economic hardship, social inequality, and inspired by Enlightenment ideals, this diverse group—encompassing peasants, urban workers, and the bourgeoisie—began to challenge the existing social and political order.

Their transformation from a marginalized majority into the National Assembly marked a radical departure from traditional power structures, asserting their role as legitimate representatives of the French people. This period was characterized by significant political mobilization and the formation of popular societies and clubs, which played a crucial role in spreading revolutionary ideas and organizing action.

This newfound empowerment of the Third Estate culminated in key revolutionary acts, such as the storming of the Bastille in July 1789, a symbol of royal tyranny. This event not only demonstrated the power of popular action but also signaled the irreversible nature of the revolutionary movement.

The rise of the Third Estate paved the way for the abolition of feudal privileges and the drafting of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen , foundational texts that sought to establish a new social and political order based on equality, liberty, and fraternity.

A People’s Monarchy

The concept of a People’s Monarchy emerged as a compromise in the early stages of the French Revolution, reflecting the initial desire among many revolutionaries to retain the monarchy within a constitutional framework.

This period was marked by King Louis XVI’s grudging acceptance of the National Assembly’s authority and the enactment of significant reforms, including the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the Constitution of 1791, which established a limited monarchy and sought to redistribute power more equitably.

However, this attempt to balance revolutionary demands with monarchical tradition was fraught with difficulties, as mutual distrust between the king and the revolutionaries continued to escalate.

The failure of the People’s Monarchy was precipitated by the Flight to Varennes in June 1791, when Louis XVI attempted to escape France and rally foreign support for the restoration of his absolute power.

This act of betrayal eroded any remaining support for the monarchy among the populace and the Assembly, leading to increased calls for the establishment of a republic.

The people’s experiment with a constitutional monarchy thus served to highlight the irreconcilable differences between the revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality and the traditional monarchical order, setting the stage for the republic’s proclamation.

Birth of a Republic

The proclamation of the First French Republic in September 1792 represented a radical departure from centuries of monarchical rule, embodying the revolutionary ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

This transition was catalyzed by escalating political tensions, military challenges, and the radicalization of the revolution, particularly after the king’s failed flight and perceived betrayal.

The Republic’s birth was a moment of immense optimism and aspiration, as it promised to reshape French society on the principles of democratic governance and civic equality. It also marked the beginning of a new calendar, symbolic of the revolutionaries’ desire to break completely with the past and start anew.

However, the early years of the Republic were marked by significant challenges, including internal divisions, economic struggles, and threats from monarchist powers in Europe.

These pressures necessitated the establishment of the Committee of Public Safety and the Reign of Terror, measures aimed at defending the revolution but which also led to extreme political repression.

Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror, from September 1793 to July 1794, remains one of the most controversial and bloodiest periods of the French Revolution. Under the auspices of the Committee of Public Safety, led by figures such as Maximilien Robespierre, the French government adopted radical measures to purge the nation of perceived enemies of the revolution.

This period saw the widespread use of the guillotine, with thousands executed on charges of counter-revolutionary activities or mere suspicion of disloyalty. The Terror aimed to consolidate revolutionary gains and protect the nascent Republic from internal and external threats, but its legacy is marred by the extremity of its actions and the climate of fear it engendered.

The end of the Terror came with the Thermidorian Reaction on 27th July 1794 (9th Thermidor Year II, according to the revolutionary calendar), which resulted in the arrest and execution of Robespierre and his closest allies.

This marked a significant turning point, leading to the dismantling of the Committee of Public Safety and the gradual relaxation of emergency measures. The aftermath of the Terror reflected a society grappling with the consequences of its radical actions, seeking stability after years of upheaval but still committed to the revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality .

Thermidorians and the Directory

Following the Thermidorian Reaction , the political landscape of France underwent significant changes, leading to the establishment of the Directory in November 1795.

This new government, a five-member executive body, was intended to provide stability and moderate the excesses of the previous radical phase. The Directory period was characterized by a mix of conservative and revolutionary policies, aimed at consolidating the Republic and addressing the economic and social issues that had fueled the revolution.

Despite its efforts to navigate the challenges of governance, the Directory faced significant opposition from royalists on the right and Jacobins on the left, leading to a period of political instability and corruption.

The Directory’s inability to resolve these tensions and its growing unpopularity set the stage for its downfall. The coup of 18 Brumaire in November 1799, led by Napoleon Bonaparte, ended the Directory and established the Consulate, marking the end of the revolutionary government and the beginning of Napoleonic rule.

While the Directory failed to achieve lasting stability, it played a crucial role in the transition from radical revolution to the establishment of a more authoritarian regime, highlighting the complexities of revolutionary governance and the challenges of fulfilling the ideals of 1789.

French Revolution End and Outcome: Napoleon’s Rise

The revolution’s end is often marked by Napoleon’s coup d’état on 18 Brumaire , which not only concluded a decade of political instability and social unrest but also ushered in a new era of governance under his rule.

This period, while stabilizing France and bringing much-needed order, seemed to contradict the revolution’s initial aims of establishing a democratic republic grounded in the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

Napoleon’s rise to power, culminating in his coronation as Emperor, symbolizes a complex conclusion to the revolutionary narrative, intertwining the fulfillment and betrayal of its foundational ideals.

Evaluating the revolution’s success requires a nuanced perspective. On one hand, it dismantled the Ancien Régime, abolished feudalism, and set forth the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, laying the cornerstone for modern democracy and human rights.

These achievements signify profound societal and legal transformations that resonated well beyond France’s borders, influencing subsequent movements for freedom and equality globally.

On the other hand, the revolution’s trajectory through the Reign of Terror and the subsequent rise of a military dictatorship under Napoleon raises questions about the cost of these advances and the ultimate realization of the revolution’s goals.

The French Revolution’s conclusion with Napoleon Bonaparte’s ascension to power is emblematic of its complex legacy. This period not only marked the cessation of years of turmoil but also initiated a new chapter in French governance, characterized by stability and reform yet marked by a departure from the revolution’s original democratic aspirations.

The Significance of the French Revolution

The French Revolution holds a place of prominence in the annals of history, celebrated for its profound impact on the course of modern civilization. Its fame stems not only from the dramatic events and transformative ideas it unleashed but also from its enduring influence on political thought, social reform, and the global struggle for justice and equality.

This period of intense upheaval and radical change challenged the very foundations of society, dismantling centuries-old institutions and laying the groundwork for a new era defined by the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

At its core, the French Revolution was a manifestation of human aspiration towards freedom and self-determination, a vivid illustration of the power of collective action to reshape the world. It introduced revolutionary concepts of citizenship and rights that have since become the bedrock of democratic societies.

Moreover, the revolution’s ripple effects were felt worldwide, inspiring a wave of independence movements and revolutions across Europe, Latin America, and beyond. Its legacy is a testament to the idea that people have the power to overthrow oppressive systems and construct a more equitable society.

The revolution’s significance also lies in its contributions to political and social thought. It was a living laboratory for ideas that were radical at the time, such as the separation of church and state, the abolition of feudal privileges, and the establishment of a constitution to govern the rights and duties of the French citizens.

These concepts, debated and implemented with varying degrees of success during the revolution, have become fundamental to modern governance.

Furthermore, the French Revolution is famous for its dramatic and symbolic events, from the storming of the Bastille to the Reign of Terror, which have etched themselves into the collective memory of humanity.

These events highlight the complexities and contradictions of the revolutionary process, underscoring the challenges inherent in profound societal transformation.

Key Figures of the French Revolution

The French Revolutions were painted by the actions and ideologies of several key figures whose contributions defined the era. These individuals, with their diverse roles and perspectives, were central in navigating the revolution’s trajectory, capturing the complexities and contradictions of this tumultuous period.

Maximilien Robespierre , often synonymous with the Reign of Terror, was a figure of paradoxes. A lawyer and politician, his early advocacy for the rights of the common people and opposition to absolute monarchy marked him as a champion of liberty.

However, as a leader of the Committee of Public Safety, his name became associated with the radical phase of the revolution, characterized by extreme measures in the name of safeguarding the republic. His eventual downfall and execution reflect the revolution’s capacity for self-consumption.

Georges Danton , another prominent revolutionary leader, played a crucial role in the early stages of the revolution. Known for his oratory skills and charismatic leadership, Danton was instrumental in the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the First French Republic.

Unlike Robespierre, Danton is often remembered for his pragmatism and efforts to moderate the revolution’s excesses, which ultimately led to his execution during the Reign of Terror, highlighting the volatile nature of revolutionary politics.

Louis XVI, the king at the revolution’s outbreak, represents the Ancient Régime’s complexities and the challenges of monarchical rule in a time of profound societal change.

His inability to effectively manage France’s financial crisis and his hesitancy to embrace substantial reforms contributed to the revolutionary fervor. His execution in 1793 symbolized the revolution’s radical break from monarchical tradition and the birth of the republic.

Marie Antoinette, the queen consort of Louis XVI, became a symbol of the monarchy’s extravagance and disconnect from the common people. Her fate, like that of her husband, underscores the revolution’s rejection of the old order and the desire for a new societal structure based on equality and merit rather than birthright.

Jean-Paul Marat , a journalist and politician, used his publication, L’Ami du Peuple, to advocate for the rights of the lower classes and to call for radical measures against the revolution’s enemies.

His assassination by Charlotte Corday, a Girondin sympathizer, in 1793 became one of the revolution’s most famous episodes, illustrating the deep divisions within revolutionary France.

Finally, Napoleon Bonaparte, though not a leader during the revolution’s peak, emerged from its aftermath to shape France’s future. A military genius, Napoleon used the opportunities presented by the revolution’s chaos to rise to power, eventually declaring himself Emperor of the French.

His reign would consolidate many of the revolution’s reforms while curtailing its democratic aspirations, embodying the complexities of the revolution’s legacy.

These key figures, among others, played significant roles in the unfolding of the French Revolution. Their contributions, whether for the cause of liberty, the maintenance of order, or the pursuit of personal power, highlight the multifaceted nature of the revolution and its enduring impact on history.

References:

(1) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, pp. 119-221.

(2) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 11-12

(3) Hobsbawm, Eric. The Age of Revolution. Vintage Books, 1996, pp. 56-57.

(4) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 24-25

(5) Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. Routledge, 2016, pp. 12-14.

(6) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 14-25

(7) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 63-65.

(8) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, pp. 242-244.

(9) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 74.

(10) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 82 – 84.

(11) Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. Routledge, 2016, p. 20.

(12) Hampson, Norman. A Social History of the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press, 1968, pp. 60-61.

(13) https://pages.uoregon.edu/dluebke/301ModernEurope/Sieyes3dEstate.pdf (14) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 104-105.

(15) French Revolution. “A Citizen Recalls the Taking of the Bastille (1789),” January 11, 2013. https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/humbert-taking-of-the-bastille-1789/.

(16) Hampson, Norman. A Social History of the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press, 1968, pp. 74-75.

(17) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 36-37.

(18) Lefebvre, Georges. The French Revolution: From its origins to 1793. Routledge, 1957, pp. 121-122.

(19) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989, pp. 428-430.

(20) Hampson, Norman. A Social History of the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press, 1968, p. 80.

(21) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 116-117.

(22) Fitzsimmons, Michael “The Principles of 1789” in McPhee, Peter, editor. A Companion to the French Revolution. Blackwell, 2013, pp. 75-88.

(23) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 68-81.

(24) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 45-46.

(25) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989,.pp. 460-466.

(26) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989, pp. 524-525.

(27) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 47-48.

(28) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 51.

(29) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 128.

(30) Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. Routledge, 2016, pp. 30 -31.

(31) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp.. 53 -62.

(32) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 129-130.

(33) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 62-63.

(34) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 156-157, 171-173.

(35) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 65-66.

(36) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989, pp. 543-544.

(37) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 179-180.

(38) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 184-185.

(39) Hampson, Norman. Social History of the French Revolution. Routledge, 1963, pp. 148-149.

(40) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 191-192.

(41) Lefebvre, Georges. The French Revolution: From Its Origins to 1793. Routledge, 1962, pp. 252-254.

(42) Hazan, Eric. A People’s History of the French Revolution, Verso, 2014, pp. 88-89.

(43) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1990, pp. 576-79.

(44) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, pp. 649-51

(45) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 242-243.

(46) Connor, Clifford. Marat: The Tribune of the French Revolution. Pluto Press, 2012.

(47) Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. Random House, 1989, pp. 722-724.

(48) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 246-47.

(49) Hampson, Norman. A Social History of the French Revolution. University of Toronto Press, 1968, pp. 209-210.

(50) Hobsbawm, Eric. The Age of Revolution. Vintage Books, 1996, pp 68-70.

(51) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 205-206

(52) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, 784-86.

(53) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 262.

(54) Schama, Simon. Citizens: a Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, Random House, 1990, pp. 619-22.

(55) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 269-70.

(56) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, p. 276.

(57) Robespierre on Virtue and Terror (1794). https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/robespierre-virtue-terror-1794/. Accessed 19 May 2020.

(58) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 290-91.

(59) Doyle, William. Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 1989, pp. 293-95.

(60) Lewis, Gwynne. The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. Routledge, 2016, pp. 49-51.

How to Cite this Article

There are three different ways you can cite this article.

1. To cite this article in an academic-style article or paper , use:

<a href=" https://historycooperative.org/the-french-revolution/ ">French Revolution: History, Timeline, Causes, and Outcomes</a>

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

French Revolution

By: History.com Editors

Updated: October 12, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The French Revolution was a watershed event in world history that began in 1789 and ended in the late 1790s with the ascent of Napoleon Bonaparte. During this period, French citizens radically altered their political landscape, uprooting centuries-old institutions such as the monarchy and the feudal system. The upheaval was caused by disgust with the French aristocracy and the economic policies of King Louis XVI, who met his death by guillotine, as did his wife Marie Antoinette. Though it degenerated into a bloodbath during the Reign of Terror, the French Revolution helped to shape modern democracies by showing the power inherent in the will of the people.

Causes of the French Revolution

As the 18th century drew to a close, France’s costly involvement in the American Revolution , combined with extravagant spending by King Louis XVI , had left France on the brink of bankruptcy.

Not only were the royal coffers depleted, but several years of poor harvests, drought, cattle disease and skyrocketing bread prices had kindled unrest among peasants and the urban poor. Many expressed their desperation and resentment toward a regime that imposed heavy taxes—yet failed to provide any relief—by rioting, looting and striking.

In the fall of 1786, Louis XVI’s controller general, Charles Alexandre de Calonne, proposed a financial reform package that included a universal land tax from which the aristocratic classes would no longer be exempt.

Estates General

To garner support for these measures and forestall a growing aristocratic revolt, the king summoned the Estates General ( les états généraux ) – an assembly representing France’s clergy, nobility and middle class – for the first time since 1614.

The meeting was scheduled for May 5, 1789; in the meantime, delegates of the three estates from each locality would compile lists of grievances ( cahiers de doléances ) to present to the king.

Rise of the Third Estate

France’s population, of course, had changed considerably since 1614. The non-aristocratic, middle-class members of the Third Estate now represented 98 percent of the people but could still be outvoted by the other two bodies.

In the lead-up to the May 5 meeting, the Third Estate began to mobilize support for equal representation and the abolishment of the noble veto—in other words, they wanted voting by head and not by status.

While all of the orders shared a common desire for fiscal and judicial reform as well as a more representative form of government, the nobles in particular were loath to give up the privileges they had long enjoyed under the traditional system.

7 Key Figures of the French Revolution

These people played integral roles in the uprising that swept through France from 1789‑1799.

The French Revolution Was Plotted on a Tennis Court

Explore some well‑known “facts” about the French Revolution—some of which may not be so factual after all.

The Notre Dame Cathedral Was Nearly Destroyed By French Revolutionary Mobs

In the 1790s, anti‑Christian forces all but tore down one of France’s most powerful symbols—but it survived and returned to glory.

Tennis Court Oath

By the time the Estates General convened at Versailles , the highly public debate over its voting process had erupted into open hostility between the three orders, eclipsing the original purpose of the meeting and the authority of the man who had convened it — the king himself.

On June 17, with talks over procedure stalled, the Third Estate met alone and formally adopted the title of National Assembly; three days later, they met in a nearby indoor tennis court and took the so-called Tennis Court Oath (serment du jeu de paume), vowing not to disperse until constitutional reform had been achieved.

Within a week, most of the clerical deputies and 47 liberal nobles had joined them, and on June 27 Louis XVI grudgingly absorbed all three orders into the new National Assembly.

The Bastille

On June 12, as the National Assembly (known as the National Constituent Assembly during its work on a constitution) continued to meet at Versailles, fear and violence consumed the capital.

Though enthusiastic about the recent breakdown of royal power, Parisians grew panicked as rumors of an impending military coup began to circulate. A popular insurgency culminated on July 14 when rioters stormed the Bastille fortress in an attempt to secure gunpowder and weapons; many consider this event, now commemorated in France as a national holiday, as the start of the French Revolution.

The wave of revolutionary fervor and widespread hysteria quickly swept the entire country. Revolting against years of exploitation, peasants looted and burned the homes of tax collectors, landlords and the aristocratic elite.

Known as the Great Fear ( la Grande peur ), the agrarian insurrection hastened the growing exodus of nobles from France and inspired the National Constituent Assembly to abolish feudalism on August 4, 1789, signing what historian Georges Lefebvre later called the “death certificate of the old order.”

How Bread Shortages Helped Ignite the French Revolution

When Parisians stormed the Bastille in 1789 they weren't only looking for arms, they were on the hunt for more grain—to make bread.

How a Scandal Over a Diamond Necklace Cost Marie Antoinette Her Head

The Diamond Necklace Affair reads like a fictional farce, but it was all true—and would become the final straw that led to demands for the queen's head.

How Versailles’ Over‑the‑Top Opulence Drove the French to Revolt

The palace with more than 2,000 rooms featured elaborate gardens, fountains, a private zoo, roman‑style baths and even 18th‑century elevators.

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

IIn late August, the Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen ( Déclaration des droits de l ’homme et du citoyen ), a statement of democratic principles grounded in the philosophical and political ideas of Enlightenment thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau .

The document proclaimed the Assembly’s commitment to replace the ancien régime with a system based on equal opportunity, freedom of speech, popular sovereignty and representative government.

Drafting a formal constitution proved much more of a challenge for the National Constituent Assembly, which had the added burden of functioning as a legislature during harsh economic times.

For months, its members wrestled with fundamental questions about the shape and expanse of France’s new political landscape. For instance, who would be responsible for electing delegates? Would the clergy owe allegiance to the Roman Catholic Church or the French government? Perhaps most importantly, how much authority would the king, his public image further weakened after a failed attempt to flee the country in June 1791, retain?

Adopted on September 3, 1791, France’s first written constitution echoed the more moderate voices in the Assembly, establishing a constitutional monarchy in which the king enjoyed royal veto power and the ability to appoint ministers. This compromise did not sit well with influential radicals like Maximilien de Robespierre , Camille Desmoulins and Georges Danton, who began drumming up popular support for a more republican form of government and for the trial of Louis XVI.

French Revolution Turns Radical

In April 1792, the newly elected Legislative Assembly declared war on Austria and Prussia, where it believed that French émigrés were building counterrevolutionary alliances; it also hoped to spread its revolutionary ideals across Europe through warfare.

On the domestic front, meanwhile, the political crisis took a radical turn when a group of insurgents led by the extremist Jacobins attacked the royal residence in Paris and arrested the king on August 10, 1792.

The following month, amid a wave of violence in which Parisian insurrectionists massacred hundreds of accused counterrevolutionaries, the Legislative Assembly was replaced by the National Convention, which proclaimed the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the French republic.

On January 21, 1793, it sent King Louis XVI, condemned to death for high treason and crimes against the state, to the guillotine ; his wife Marie-Antoinette suffered the same fate nine months later.

Reign of Terror

Following the king’s execution, war with various European powers and intense divisions within the National Convention brought the French Revolution to its most violent and turbulent phase.

In June 1793, the Jacobins seized control of the National Convention from the more moderate Girondins and instituted a series of radical measures, including the establishment of a new calendar and the eradication of Christianity .

They also unleashed the bloody Reign of Terror (la Terreur), a 10-month period in which suspected enemies of the revolution were guillotined by the thousands. Many of the killings were carried out under orders from Robespierre, who dominated the draconian Committee of Public Safety until his own execution on July 28, 1794.

Did you know? Over 17,000 people were officially tried and executed during the Reign of Terror, and an unknown number of others died in prison or without trial.

Thermidorian Reaction

The death of Robespierre marked the beginning of the Thermidorian Reaction, a moderate phase in which the French people revolted against the Reign of Terror’s excesses.

On August 22, 1795, the National Convention, composed largely of Girondins who had survived the Reign of Terror, approved a new constitution that created France’s first bicameral legislature.

Executive power would lie in the hands of a five-member Directory ( Directoire ) appointed by parliament. Royalists and Jacobins protested the new regime but were swiftly silenced by the army, now led by a young and successful general named Napoleon Bonaparte .

French Revolution Ends: Napoleon’s Rise

The Directory’s four years in power were riddled with financial crises, popular discontent, inefficiency and, above all, political corruption. By the late 1790s, the directors relied almost entirely on the military to maintain their authority and had ceded much of their power to the generals in the field.

On November 9, 1799, as frustration with their leadership reached a fever pitch, Napoleon Bonaparte staged a coup d’état, abolishing the Directory and appointing himself France’s “ first consul .” The event marked the end of the French Revolution and the beginning of the Napoleonic era, during which France would come to dominate much of continental Europe.

Photo Gallery

French Revolution. The National Archives (U.K.) The United States and the French Revolution, 1789–1799. Office of the Historian. U.S. Department of State . Versailles, from the French Revolution to the Interwar Period. Chateau de Versailles . French Revolution. Monticello.org . Individuals, institutions, and innovation in the debates of the French Revolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences .

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

IMAGES

VIDEO