Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6 Chapter 6: Progressivism

Dr. Della Perez

This chapter will provide a comprehensive overview of Progressivism. This philosophy of education is rooted in the philosophy of pragmatism. Unlike Perennialism, which emphasizes a universal truth, progressivism favors “human experience as the basis for knowledge rather than authority” (Johnson et. al., 2011, p. 114). By focusing on human experience as the basis for knowledge, this philosophy of education shifts the focus of educational theory from school to student.

In order to understand the implications of this shift, an overview of the key characteristics of Progressivism will be provided in section one of this chapter. Information related to the curriculum, instructional methods, the role of the teacher, and the role of the learner will be presented in section two and three. Finally, key educators within progressivism and their contributions are presented in section four.

Characteristics of Progressivim

6.1 Essential Questions

By the end of this section, the following Essential Questions will be answered:

- In which school of thought is Perennialism rooted?

- What is the educational focus of Perennialism?

- What do Perrenialists believe are the primary goals of schooling?

Progressivism is a very student-centered philosophy of education. Rooted in pragmatism, the educational focus of progressivism is on engaging students in real-world problem- solving activities in a democratic and cooperative learning environment (Webb et. al., 2010). In order to solve these problems, students apply the scientific method. This ensures that they are actively engaged in the learning process as well as taking a practical approach to finding answers to real-world problems.

Progressivism was established in the mid-1920s and continued to be one of the most influential philosophies of education through the mid-1950s. One of the primary reasons for this is that a main tenet of progressivism is for the school to improve society. This was sup posed to be achieved by engaging students in tasks related to real-world problem-solving. As a result, progressivism was deemed to be a working model of democracy (Webb et. al., 2010).

6.2 A Closer Look

Please read the following article for more information on progressivism: Progressive education: Why it’s hard to beat, but also hard to find. As you read the article, think about the following Questions to Consider:

- How does the author define progressive education?

- What does the author say progressive education is not?

- What elements of progressivism make sense, according to the author?

Progressive education: Why it’s hard to beat, but also hard to find

6.3 Essential Questions

- How is a progressivist curriculum best described?

- What subjects are included in a progressivist curriculum?

- Do you think the focus of this curriculum is beneficial for students? Why or why not?

As previously stated, progressivism focuses on real-world problem-solving activities. Consequently, the progressivist curriculum is focused on providing students with real-world experiences that are meaningful and relevant to them rather than rigid subject-matter content.

Dewey (1963), who is often referred to as the “father of progressive education,” believed that all aspects of study (i.e., arithmetic, history, geography, etc.) need to be linked to materials based on students every- day life-experiences.

However, Dewey (1938) cautioned that not all experiences are equal:

The belief that all genuine education comes about through experience does not mean that all experiences are genuinely or equally educative. Experience and education cannot be directly equated to each other. For some experiences are mis-educative. Any experience is mis-education that has the effect of arresting or distorting the growth or further experience (p. 25).

An example of miseducation would be that of a bank robber. He or she many learn from the experience of robbing a bank, but this experience can not be equated with that of a student learning to apply a history concept to his or her real-world experiences.

Features of a Progressive Curriculum

There are several key features that distinguish a progressive curriculum. According to Lerner (1962), some of the key features of a progressive curriculum include:

- A focus on the student

- A focus on peers

- An emphasis on growth

- Action centered

- Process and change centered

- Equality centered

- Community centered

To successfully apply these features, a progressive curriculum would feature an open classroom environment. In this type of environment, students would “spend considerable time in direct contact with the community or cultural surroundings beyond the confines of the classroom or school” (Webb et. al., 2010, p. 74). For example, if students in Kansas were studying Brown v. Board of Education in their history class, they might visit the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site in Topeka. By visiting the National Historic Site, students are no longer just studying something from the past, they are learning about history in a way that is meaningful and relevant to them today, which is essential in a progressive curriculum.

- In what ways have you experienced elements of a progressivist curriculum as a student?

- How might you implement a progressivist curriculum as a future teacher?

- What challenges do you see in implementing a progressivist curriculum and how might you overcome them?

Instruction in the Classroom

6.4 Essential Questions

- What are the main methods of instruction in a progressivist classroom?

- What is the teachers role in the classroom?

- What is the students role in the classroom?

- What strategies do students use in a progressivist classrooms?

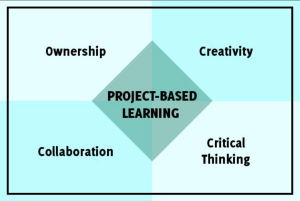

Within a progressivist classroom, key instructional methods include: group work and the project method. Group work promotes the experienced-centered focus of the progressive philosophy. By giving students opportunities to work together, they not only learn critical skills related to cooperation, they are also able to engage in and develop projects that are meaningful and have relevance to their everyday lives.

Promoting the use of project work, centered around the scientific method, also helps students engage in critical thinking, problem solving, and deci- sion making (Webb et. al., 2010). More importantly, the application of the scientific method allows progressivists to verify experi ence through investigation. Unlike Perennialists and essentialists, who view the scientific method as a means of verifying the truth (Webb et. al., 2010).

Teachers Role

Progressivists view teachers as a facilitator in the classroom. As the facilitator, the teacher directs the students learning, but the students voice is just as important as that of the teacher. For this reason, progressive education is often equated with student-centered instruction.

To support students in finding their own voice, the teacher takes on the role of a guide. Since the student has such an important role in the learning, the teacher needs to guide the students in “learning how to learn” (Labaree, 2005, p. 277). In other words, they need to help students construct the skills they need to understand and process the content.

In order to do this successfully, the teacher needs to act as a collaborative partner. As a collaborative partner, the teachers works with the student to make group decisions about what will be learned, keeping in mind the ultimate out- comes that need to be obtained. The primary aim as a collaborative partner, according to progressivists, is to help students “acquire the values of the democratic system” (Webb et. al., 2010, p. 75).

Some of the key instructional methods used by progressivist teachers include:

- Promoting discovery and self-directly learning.

- Integrating socially relevant themes.

- Promoting values of community, cooperation, tolerance, justice, and democratic equality.

- Encouraging the use of group activities.

- Promoting the application of projects to enhance learning.

- Engaging students in critical thinking.

- Challenging students to work on their problem solving skills.

- Developing decision making techniques.

- Utilizing cooperative learning strategies. (Webb et. al., 2010).

6.5 An Example in Practice

Watch the following video and see how many of the bulleted instructional methods you can identify! In addition, while watching the video, think about the following questions:

- Do you think you have the skills to be a constructivist teacher? Why or why not?

- What qualities do you have that would make you good at applying a progressivist approach in the classroom? What would you need to improve upon?

Based on the instructional methods demonstrated in the video, it is clear to see that progressivist teachers, as facilitators of students learning, are encouraged to help their stu dents construct their own understanding by taking an active role in the learning process. Therefore, one of the most com- mon labels used to define this entire approach to education to- day is: constructivism .

Students Role

Students in a progressivist classroom are empowered to take a more active role in the learning process. In fact, they are encourage to actively construct their knowledge and understanding by:

- Interacting with their environment.

- Setting objectives for their own learning.

- Working together to solve problems.

- Learning by doing.

- Engaging in cooperative problem solving.

- Establishing classroom rules.

- Evaluating ideas.

- Testing ideas.

The examples provided above clearly demonstrate that in the progressive classroom, the students role is that of an active learner.

6.6 An Example in Practice

Mrs. Espenoza is an 6th grade teacher at Franklin Elementary. She has 24 students in her class. Half of her students are from diverse cultural- backgrounds and are receiving free and reduced lunch. In order to actively engage her students in the learning process, Mrs. Espenoza does not use traditional textbooks in her classroom. Instead, she uses more real-world resources and technology that goes beyond the four walls of the classroom. In order to actively engage her students in the learning process, she seeks out members of the community to be guest presenters in her classroom as she believes this provides her students with an way to interact with/learn about their community. Mrs. Espenoza also believes it is important for students to construct their own learning, so she emphasizes: cooperative problem solving, project-based learning, and critical thinking.

6.7 A Closer Look

For more information about progressivism, please watch the following videos. As you watch the videos, please use the “Questions to Consider” as a way to reflect on and monitor your own learnings.

• What additional insights did you gain about the progressivist philosophy?

• Can you relate elements of this philosophy to your own educational experiences? If so, how? If not, can you think of an example?

Key Educators

6.8 Essential Questions

- Who were the key educators of Progressivism?

- What impact did each of the key educators of Progressivism have on this philosophy of education?

The father of progressive education is considered to be Francis W. Parker. Parker was the superintendent of schools in Quincy, Massachusetts, and later became the head of the Cook County Normal School in Chicago (Webb et. al., 2010). John Dewey is the American educator most commonly associated with progressivism. William H. Kilpatrick also played an important role in advancing progressivism. Each of these key educators, and their contributions, will be further explored in this section.

Francis W. Parker (1837 – 1902)

Francis W. Parker was the superintendent of schools in Quincy, Massachusetts (Webb, 2010). Between 1875 – 1879, Parker developed the Quincy plan and implemented an experimental program based on “meaningful learning and active understanding of concepts” (Schugurensky, 2002, p. 1). When test results showed that students in Quincy schools outperformed the rest of the school children in Massachusetts, the progressive movement began.

Based on the popularity of his approach, Parker founded the Parker School in 1901. The Parker School

“promoted a more holistic and social approach, following Francis W. Parker’s beliefs that education should include the complete development of an individual (mental, physical, and moral) and that education could develop students into active, democratic citizens and lifelong learners” (Schugurensky, 2002, p. 2).

Parker’s student-centered approach was a dramatic change from the prescribed curricula that focused on rote memorization and rigid student disciple. However, the success of the Parker School could not be disregarded. Alumni of the school were applying what they learned to improve their community and promote a more democratic society.

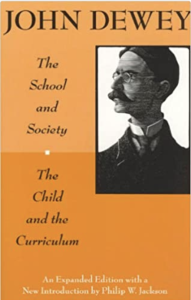

John Dewey (1859 – 1952)

John Dewey’s approach to progressivism is best articulated in his book: The School and Society

(1915). In this book, he argued that America needed new educational systems based on “the larger whole of social life” (Dewey, 1915, p. 66). In order to achieve this, Dewey proposed actively engaging students in inquiry-based learning and experimentation to promote active learning and growth among students.

As a result of his work, Dewey set the foundation for approaching teaching and learning from a student-driven perspective. Meaningful activities and projects that actively engaging the students’ interests and backgrounds as the “means” to learning were key (Tremmel, 2010, p. 126). In this way, the students could more fully develop as learning would be more meaningful to them.

6.9 A Closer Look

For more information about Dewey and his views on education, please read the following article titled: My Pedagogic Creed. This article is considered Dewey’s famous declaration concerning education as presented in five key articles that summarize his beliefs.

My Pedagogic Creed

William H. Kilpatrick (1871-1965)

Kilpatrick is best known for advancing progressive education as a result of his focus on experience-centered curriculum. Kilpatrick summarized his approach in a 1918 essay titled “The Project Method.” In this essay, Kilpatrick (1918) advocated for an educational approach that involves

“whole-hearted, purposeful activity proceeding in a social environment” (p. 320).

As identified within The Project Method, Kilpatrick (1918) emphasized the importance of looking at students’ interests as the basis for identifying curriculum and developing pedagogy. This student-centered approach was very significant at the time, as it moved away from the traditional approach of a more mandated curriculum and prescribed pedagogy.

Although many aspects of his student-centered approach were highly regarded, Kilpatrick was also criticized given the diminished importance of teachers in his approach in favor of the students interests and his “extreme ideas about student- centered action” (Tremmel, 2010, p. 131). Even Dewey felt that Kilpatrick did not place enough emphasis on the importance of the teacher and his or her collaborative role within the classroom.

Reflect on your learnings about Progressivism! Create a T-chart and bullet the pros and cons of Progressivism. Based on your T-chart, do you think you could successfully apply this philosophy in your future classroom? Why or why not?

Chapter 6: Progressivism Copyright © 2023 by Dr. Della Perez. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- Teaching Life

Five Steps to Create a Progressive Student-Centered Classroom

- Posted by by Zaraki Kenpachi

- 4 years ago

Introduction:

The education system of today finds itself grappling with the challenges of an outdated structure and teaching methods that no longer effectively engage and inspire students. In a rapidly evolving world, relying on old textbooks and conventional techniques falls short of preparing learners for the future. The rise of a tech-savvy generation, adept at utilizing mobile phones and computers, calls for a paradigm shift in education. This is where the concept of Progressivism in education, originally envisioned by John Dewey in 1880, emerges as a holistic and student-centric approach that aligns with the needs of the modern era.

Progressivism in Education: A Holistic Approach

Progressivism in education entails a student-centered learning approach that emphasizes equality among class members, including the instructor. It fosters a structured learning pattern in which teachers assume the role of coaches or guides rather than the sole source of knowledge. This shift limits the teacher’s responsibilities and creates an environment conducive to creativity, as students engage with the instructor’s guidance while generating their own ideas. By prioritizing progressivism, we take the first step toward preparing students for success in a rapidly changing world.

Promoting Meaningful Interactions and Critical Thinking:

In contrast to traditional schooling, where teachers take center stage and share knowledge, progressive education places students at the focal point. Within a student-centered classroom, students engage in meaningful interactions that foster collaboration and critical thinking. Teachers act as facilitators, encouraging students to discuss, analyze, and generate their own solutions to problems. This approach cultivates responsible members of society who can effectively navigate real-world challenges, equipped with strong interpersonal skills and the ability to think critically.

Teaching Students to Be Good Humans:

The progressive education system goes beyond academics to focus on the holistic development of students. It aims to cultivate social responsibility and empathy by providing opportunities for classes on human rights, ethics, and social issues. Through open discussions and debates, students develop an interest in societal matters and learn how to articulate their thoughts effectively. This comprehensive approach ensures that students not only acquire knowledge but also develop into well-rounded human beings with a deep understanding of the world around them.

The 5 Steps of Progressivism in Education:

- Step 1: Create Ongoing Projects: Implementing ongoing projects in the classroom is a transformative aspect of progressivism in education. Ongoing projects provide students with hands-on, immersive learning experiences that extend beyond the boundaries of traditional classroom instruction. Students work collaboratively in teams, engaging in research, planning, and executing long-term projects. This process allows them to develop crucial skills such as time management, problem-solving, critical thinking, and effective communication.

- Step 2: Integrate Technology: Incorporating technology into the classroom is essential in the 21st century. Progressive education recognizes the importance of leveraging technology as a tool for learning and problem-solving. By integrating technology, students gain access to a vast array of resources, engage in interactive learning activities, and develop digital literacy skills. Technology also enables personalized learning experiences, catering to individual students’ needs and interests, and promotes global connectivity and collaboration.

- Step 3: Switch Homework with In-Class Activities: Progressive education challenges the traditional practice of assigning excessive homework and instead focuses on in-class activities. By engaging students in interactive tasks and projects during class time, educators create an environment that fosters collaboration, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills. In-class activities provide immediate guidance and support, allowing students to learn from their peers and develop effective communication and teamwork skills. This approach enhances student engagement and creates a positive and dynamic learning environment.

- Step 4: Break the Chains of Rules and Regulations: Progressive education challenges the notion of strict rules and regulations in the classroom. Instead, it advocates for creating a learning environment where students are intrinsically motivated to seek knowledge. By fostering a culture of curiosity, exploration, and passion for learning, progressive education minimizes the need for behavioral rules. Students are encouraged to take ownership of their learning, make independent decisions, and explore their interests, thereby promoting self-discipline and responsibility.

- Step 5: Create a Student-Based Evaluation: Progressive education redefines the evaluation process by shifting from teacher-centric to student-centric evaluation. Feedback becomes a fundamental aspect of assessing student performance, involving both students and teachers in the evaluation process. This approach encourages students to take an active role in their learning, reflect on their progress, and set goals for further growth. Through self-assessment, peer assessment, and teacher guidance, students gain a deeper understanding of their strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement. This student-based evaluation cultivates a growth mindset, fosters intrinsic motivation, and promotes a deeper engagement with the learning process.

Historical Context of Progressivism in Education:

The historical context of progressivism in education is crucial to understanding its significance and impact. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, educational practices were primarily focused on rote memorization and strict discipline. However, thinkers like John Dewey challenged this traditional approach and advocated for a more student-centered and experiential learning model. Dewey’s groundbreaking ideas emphasized the importance of hands-on learning, critical thinking, and connecting education to real-life experiences.

During Dewey’s time, industrialization and social changes were reshaping society. There was a growing recognition that education needed to adapt to meet the demands of an evolving world. Progressivism in education emerged as a response to these changing needs, aiming to prepare students for active citizenship and meaningful engagement in society. Dewey’s progressive ideas influenced numerous educators and institutions, laying the foundation for student-centered approaches that prioritize individual growth, collaboration, and practical problem-solving.

Real-Life Examples and Case Studies:

Real-life examples and case studies vividly illustrate the transformative power of progressivism in education. One such example is the High Tech High (HTH) network of schools in California. HTH embodies progressivism by integrating project-based learning, student agency, and the integration of technology into the curriculum. Students at HTH engage in interdisciplinary projects, working collaboratively to address real-world issues. The results have been remarkable, with students exhibiting higher levels of critical thinking, creativity, and a deep sense of ownership over their learning.

Another inspiring case study is the Big Picture Learning network. This network of schools takes a personalized and student-centered approach, tailoring education to individual student interests and goals. Students engage in internships and real-world experiences, developing essential skills and exploring their passions. The success of Big Picture Learning is evident in the high graduation rates, increased student engagement, and the impressive post-secondary success of its graduates.

These examples demonstrate that progressivism in education is not just a theoretical concept; it has been successfully implemented in diverse educational settings. Students thrive when they are actively involved in their learning, have the opportunity to apply knowledge in meaningful ways, and are empowered to pursue their interests.

Addressing Potential Challenges and Criticisms:

Implementing progressivism in education is not without its challenges and criticisms. Some concerns revolve around managing large class sizes while ensuring individualized attention, meeting curriculum requirements, and preparing students for standardized testing. However, proponents of progressivism argue that with thoughtful planning and support, these challenges can be overcome.

For instance, employing effective classroom management strategies, promoting student autonomy, and fostering a culture of respect and responsibility can help address concerns about large class sizes. By implementing flexible and interdisciplinary curriculum frameworks, educators can integrate required content while allowing students to explore their interests and engage in authentic, real-world problem-solving.

Critics often worry that progressivism may neglect foundational knowledge and lead to gaps in students’ learning. However, progressive education does not disregard essential knowledge but rather approaches it in a more contextualized and relevant manner. It emphasizes the importance of critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving skills while ensuring that foundational knowledge is acquired through integrated and meaningful learning experiences.

By addressing these challenges head-on and providing evidence-based strategies, progressivism in education can offer a holistic and effective approach to teaching and learning.

Professional Development and Teacher Training:

To successfully implement progressivism in education, professional development and teacher training play a crucial role. Educators need to be equipped with the knowledge, skills, and pedagogical approaches necessary to create student-centered classrooms.

Professional development programs can provide teachers with training on project-based learning, assessment strategies, technology integration, and fostering student agency. Collaborative learning communities, mentorship programs, and ongoing support are essential components of effective professional development initiatives. By investing in comprehensive teacher training, educational institutions can ensure that educators have the necessary tools and strategies to create transformative learning environments.

Additionally, universities and teacher education programs need to incorporate progressivism in their curricula and prepare future educators to embrace student-centered approaches. Pre-service teachers should be exposed to progressive educational philosophies, provided with practical classroom experiences, and supported in reflecting on their teaching practices.

By prioritizing professional development and teacher training, educators can enhance their instructional practices, foster a culture of continuous learning, and effectively implement progressivism in education.

Research and Evidence:

A robust body of research supports the benefits of progressivism in education. Studies have consistently shown that student-centered approaches improve student engagement, critical thinking skills, creativity, and overall academic achievement.

Research has found that project-based learning, a core element of progressivism, promotes deeper understanding, application of knowledge, and increased motivation among students. Students engaged in project-based learning demonstrate higher levels of problem-solving skills, collaboration, and communication, which are essential skills for success in the 21st century.

Furthermore, studies indicate that progressivism in education positively impacts students’ social-emotional development. It fosters a sense of belonging, self-efficacy, and a growth mindset, leading to increased academic confidence and overall well-being.

The research also highlights the long-term benefits of progressivism, showing that students who experience student-centered approaches are more likely to pursue higher education, succeed in their careers, and become lifelong learners.

By incorporating evidence-based practices, educators and policymakers can make informed decisions and further promote progressivism in education for the betterment of students’ learning outcomes and future success.

Conclusion:

The progressive education system represents a paradigm shift in the way we approach teaching and learning. By prioritizing student-centered classrooms, promoting critical thinking, and fostering experiential learning, progressivism equips students with the skills necessary to navigate the complexities of the modern world. The implementation of ongoing projects, technology integration, in-class activities, rule flexibility, and student-based evaluation are essential steps toward creating a progressive educational environment that prepares students for success in the 21st century and beyond. By embracing progressivism in education, we can revolutionize the way we educate future generations, ensuring they are equipped with the tools, mindset, and competencies needed to thrive in an ever-changing world. The transformative potential of progressivism paves the way for an education system that nurtures independent thinkers, problem solvers, and lifelong learners.

Related Posts:

- Create an English Curriculum for Your Class [Updated]

- Grouping Students in a Classroom

- Top 10 Classroom Hacks for Teachers

- The 10 Most Important Classroom Rules [Updated]

- How to Control Classroom Noise [Updated]

- Brag Tags For Students [Ideas for The Classroom]

Post navigation

Mindfulness in Education

Modal Verbs Deduction Activities [Updated]

Progressive Education Philosophy: examples & criticisms

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

The progressive education philosophy emphasizes the development of the whole child: physical, emotional, and intellectual. Learning is based on the individual needs, abilities, and interests of the student. This leads to students being motivated and enthusiastic about learning.

Progressive philosophy further emphasizes that instruction should be centered on learning by doing, problem-based, experiential, and involve collaboration.

When these elements are included in the learning experience, then students learn practical skills, become engaged in the process, and learning will be maximized.

Progressive Education Definition

The progressive movement has its roots in the writings of philosophers such as John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Those postulations regarding education influenced other scholars, including Maria Montessori and John Dewey.

The premise of the progressive movement is that traditional educational practices lack relevance to students and that the memorization of facts is ineffective.

As Dewey stated in his book Experience and Education (1938),

“The traditional scheme is, in essence, one of imposition from above and from outside. It imposes adult standards, subject-matter, and methods upon those who are only growing slowly toward maturity” (p. 5-6).

As a response, progressive educators tend to emphasize hands-on, experiential methodologies that enable the construction of knowledge in the mind rather than mere memorization.

Progressive educators also advocate for student autonomy and the cultivation of democratic values and principles by empowering students to make their own decisions as much as possible.

This pedagogy is distinguished by its less authoritarian structure and more collaborative classrooms, with the teacher acting as a guide and collaborator rather than the sole knowledge holder.

Progressive Education Examples

The following pedagogies and pedagogical strategies are often considered commensurate with a progressive education philosophy:

- Project-based learning

- Problem-based learning

- Inquiry-based learning

- Service learning

- Student-centered learning

- Self-directed learning

- Place-based education

- Montessori education

- Community-based learning

- Co-operative learning

- Constructivist learning

- Authentic assessment

- Action research

- Active learning

- Experiential education

- Personalized learning

Real-Life Examples

- A third-grade teacher places cardboard boxes, paper towel tubes, tape, and scissors on a table so the students can design and construct marble mazes.

- Dr. Singh has his students work in small teams to write a program that will block a computer virus attack. The teams then take part in a class competition.

- On the first day of school, Mrs. Jones allows her students to generate a list of classroom rules and learning principles.

- Students in this history class work in small groups to write a short play about an event of their choosing in the Civil Rights movement.

- During a leadership training workshop, the facilitator arranges for pairs of participants to engage in conflict resolution role plays.

- To build teamwork and communication skills, high school students work collaboratively to create PowerPoint presentations about what they learned instead of taking exams.

- Mr. Gonzalez has his students debate the pros and cons of political ideologies on social equality.

- Students in an early childhood education course work in small groups to develop an Action Plan for handling a contagious disease outbreak at a primary school.

- Every term, this high school awards 5 students for exemplifying leadership in the classroom.

- Students in this university Hospitality Management course visit one local 5-star hotel restaurant and conduct a customer service analysis.

Case Studies

1. service-oriented learning: urban farming.

Progressive education can also contain elements of social reconstructionism and the goal of making the world a better place to live. Today’s version of making the world a better place to live encompasses environmental concerns.

For example, food insecurity is a matter that is not evenly distributed across all SES demographics.

Therefore, schools should help students develop a sense of responsibility and build skills that address a broad range of social issues .

The BBC reports that 900 million tons of food is wasted every year. That is more than enough to feed those in need. It is also a problem that has many possible solutions; one of them being Urban farming .

University agriculture majors can coordinate with local disadvantaged communities to implement urban farming solutions. It is possible to grow food on abandoned lots, rooftops, and on the outside walls of buildings and houses.

This is exactly the type of problem-based cooperative learning activity that progressivists support, for several reasons. The students address a pressing societal need and at the same time develop valuable practical skills.

2. Developing Practical Skills: Minecraft

Progressive education means developing practical skills, integrating technology when possible, and tapping into the interests of students. The Minecraft education package meets all of those objectives.

It offers teachers a game-based learning platform that students find very exciting and teachers find very educational. The education edition includes games that foster creativity , problem-solving skills, and cooperative learning.

Teachers in Ireland use Minecraft to demonstrate the connections between history, science, and technology. In one activity , students pretend to be Vikings. They get to build ships and go on raids to establish settlements in faraway lands.

The students learn about archeological reconstruction and how to storyboard their adventures by creating their own digital Viking saga.

As the principal explains, the kids are having great fun, but at the same time they are developing fundamental problem-solving skills , learning to cooperate with each other, and all the while expanding their knowledge base. It’s a win-win-win situation.

3. Student-Centered Learning: Provocations

Teachers at a primary school in Australia have developed a unique student-centered approach that motivates students and allows them to explore their own interests.

The teachers write various learning tasks on cards, called Provocations, and place them on a bulletin board. Students select the tasks they find most interesting and then go to a designated place in the classroom that has been equipped with the necessary materials.

Students then work alone or individually to complete the task. When they’re finished, they write about what they did and convey their reflections in a Learning Journey book.

Afterwards, the teacher and student go through the book and discuss the student’s experience.

The teacher can highlight key learning concepts and the student can consider what they would do differently in the future.

One of the key benefits of this type of activity is that students develop a sense of responsibility for their learning outcomes.

4. Cooperative Learning: Think-Pair-Share

In traditional educational approaches, students are passive recipients of information. They receive and then recall input on exams to demonstrate learning. From a progressive philosophy, this approach fails in so many ways. It does nothing to build practical skills, the level of student motivation is low, and the level of processing is shallow.

Originally proposed by Frank Lyman (1981), Think-Pair-Share (TPS) is just the opposite. It utilizes cooperative learning to improve student engagement, allows students to process information at a much deeper level, and builds teamwork and communication skills.

The instructor presents an issue for students to reflect on individually. Next, pairs discuss their views and arrive at a mutual understanding, which is then shared with the class.

After all pairs have taken a turn, the instructor engages the class with a broader discussion that can allow key concepts and facts to be highlighted.

TPS is a great way to get students involved and build their teamwork and communication skills.

5. Problem-Based Learning: Medical School

One of the key features of progressive education is that students develop practical skills. Problem-based learning (PBL) is often mentioned as a key instructional approach because it helps students develop practical skills and is collaborative. Some of the most respected medical schools in the world have integrated PBL into the curriculum.

Students are presented with a clinical problem. The file may consist of several binders of patient test results and other data. Students then form teams and work together to reach a diagnosis and treatment plan.

A thorough discussion of the patient’s information will reveal the team’s knowledge gaps. The team will then devise a set of learning objectives and path of study to pursue. Each member of the team is allocated specific tasks, the results of which are then shared at the next meeting.

PBL maximizes student engagement, exercises higher-order thinking , and improves collaboration and communication skills. All key goals of progressive education.

1. Practical Skills Development

Progressive education contains many features of other learning approaches such as problem-based learning and experiential learning. These approaches cultivate practical skills such as teamwork, conflict resolution, and communication.

Because students are “doing something” they develop practical skills. For example, in a marketing course, students will design a campaign. In a management course, students will practice giving performance feedback or conducting team-building activities.

These are the types of skills that students will apply later in life at work and in their careers.

2. Self-Discipline and Responsibility

Most activities in progressive education are student-centered. Students are the focus and often this means that they choose their learning goals and work autonomously .

This results in students learning that they are responsible for their learning outcomes. To accomplish tasks, the teacher is not there standing over their shoulder and coaxing them onward. Students must learn how to pace themselves and stay on-task during class. This builds self-discipline and responsibility.

3. Higher-Order Thinking

In a traditional classroom, students passively receive information transmitted from the teacher. The goal is to commit that information to rote memory so that it can be later used to answer multiple-choice questions. This limits the depth and quality of processing students must engage.

Progressive educational activities are just the opposite. Because students must engage in active learning, they process the information much deeper. Because they are required to engage in problem-solving and critical thinking, they must exercise higher-order thinking skills.

1. It Lacks Structure

Not all students flourish in a progressive classroom. Some students benefit from having well-structured lessons that are directed by the teacher. When an activity lacks these components, some students feel uncomfortable and anxious.

However, when there are clear objectives and learning tasks, they feel at ease and motivated. Without structure they can become overwhelmed with uncertainty and reluctant to get started.

2. Clashes with Teachers’ Preferences

Similar to students, not all teachers enjoy working in a progressive school. They find the lack of structure and clarity on learning outcomes difficult to grapple with.

These teachers work much better when they have a firm set of objectives they need their students to achieve; everything is clearly defined.

3. Overwhelming Work Load

The amount of work involved to create several different activities that can suit the variety of learning styles in one classroom can be overwhelming.

It takes a great deal of time just to think of so many meaningful activities, and then, one must prepare a wide assortment of materials; all for a single lesson.

Teachers in many public schools already feel overwhelmed with job demands. Many teachers casually remark that they have not one second of free time from September to June, and that includes weekends. It is hard to justify such a demanding job when taken in the context of the level of commitment required, and of course, a disappointing pay scale.

Progressive education seeks to help students develop skills that they will need throughout their lifespan. By implementing activities that foster problem-solving, higher-order thinking, cooperation, and practical skills, students will graduate well-prepared for their future.

Although these are admirable goals, there are some drawbacks. The demands on teachers are substantial, as it takes a great deal of time to think of and prepare all of the necessary materials for a single lesson.

Moreover, not all students benefit from such an unstructured environment. Some students function better in an atmosphere with clearly defined goals and teacher guidance.

Ultimately, each parent must decide on which approach they consider best for their child and try to locate a school that subscribes to that philosophy.

Hayes, W. (2006). The progressive education movement: Is it still a factor in today’s schools? Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education . Toronto: Collier-MacMillan Canada Ltd.

Lyman, F. (1981). The responsive classroom discussion: The inclusion of all students. In A. Anderson (Ed.), Mainstreaming digest (pp. 109-113). University of Maryland College of Education.

Macrine, Sheila. (2005). The promise and failure of progressive education-essay review. Teachers College Record, 107 , 1532-1536. https://10.1177/016146810510700705

Wright, G. B. (2011). Student-centered learning in higher education. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 23(3), 93–94.

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Call Us: 212-301-7764

Progressivism in Educational Philosophy

July 2, 2024

Unleash the power of progressivism in education! Explore its core tenets, teaching methods, and impact on modern learning practices.

Understanding Progressivism in Education

Progressivism is an educational philosophy that places a strong emphasis on the use of human experience as the basis for knowledge, shifting the focus from authority to the individual student. It emerged in the mid-1920s and continued to be one of the most influential educational philosophies until the mid-1950s. The core tenets of progressivism encompass a belief in the importance of experiential learning, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills.

Core Tenets of Progressivism

Progressivism in educational philosophy is rooted in pragmatism, which emphasizes the practical application of knowledge. The core tenets of progressivism include:

- Experiential Learning : Progressivism emphasizes the importance of learning through direct experience and active engagement. Students are encouraged to explore and interact with their environment, acquiring knowledge and skills through hands-on activities and real-world problem-solving tasks.

- Student-Centered Approach : Progressivism shifts the focus from the school as an institution to the needs and interests of the individual student. It recognizes that each student is unique and promotes personalized learning experiences that cater to their abilities, interests, and aspirations.

- Collaborative Learning : Progressivism promotes collaborative learning environments where students work together in groups, sharing ideas, perspectives, and knowledge. This fosters social skills, teamwork, and the ability to engage in constructive dialogue.

- Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving : Progressivism encourages the development of critical thinking skills, enabling students to analyze, evaluate, and apply information in a meaningful way. Problem-solving becomes a central aspect of the learning process, allowing students to tackle real-world challenges and develop innovative solutions.

Historical Perspective

Progressivism emerged as a response to the traditional educational practices of the time, which were often rigid and focused primarily on rote memorization. It sought to transform education by making it more relevant and engaging for students. The philosophy gained momentum in the early 20th century with influential educators like John Dewey, who played a significant role in shaping the progressive movement in education.

By embracing progressivism in education, educators sought to empower students, promote active learning, and prepare them for the challenges of the real world. Today, the principles of progressivism continue to influence educational practices, shaping modern approaches to teaching and learning.

In the following sections, we will explore the influence of John Dewey and the progressive curriculum, as well as the teaching methods and role of the teacher in a progressive classroom. We will also examine the application of progressivism in modern education, including its impact on learning practices and the challenges and adaptations faced by educators.

John Dewey's Influence

John Dewey, a prominent figure in progressivism, had a significant influence on the philosophy of education. His ideas centered around the importance of practical learning and critical thinking in the educational process.

Emphasis on Practical Learning

Dewey believed that education should not solely focus on rote memorization and theoretical knowledge. Instead, he emphasized the need for practical learning experiences that engage students in hands-on projects and real-life problem-solving activities. According to Dewey, this approach enables students to apply their knowledge in practical situations and develop a deeper understanding of the subject matter.

By integrating practical learning into the curriculum, students can develop essential life skills that are applicable in real-life situations. This approach goes beyond the classroom and prepares students for the complexities of daily life. They learn how to tackle practical tasks, such as changing a tire or preparing a meal, and acquire critical life skills, such as managing finances and making informed decisions. This emphasis on practical learning ensures that education is continuous and relevant to students' lives.

Critical Thinking Approach

Another key aspect of Dewey's influence on progressivism in education is his emphasis on critical thinking. Dewey believed that students should actively engage in problem-solving and inquiry-based learning to develop their cognitive abilities. He argued that education should go beyond the transmission of information and encourage students to develop their own ideas, make connections, and think critically about the world around them.

By adopting a critical thinking approach, students are encouraged to question, analyze, and evaluate information. They develop the skills to think independently, solve problems creatively, and make informed decisions. Dewey recognized that these skills are essential for success in a rapidly changing world, where adaptability and critical thinking are highly valued.

Incorporating Dewey's principles of practical learning and critical thinking into educational practices allows students to actively participate in their own learning journey. It fosters a sense of ownership and engagement, enabling students to develop not only knowledge but also the skills and mindset necessary for lifelong learning and success.

The Progressive Curriculum

In the realm of progressivism in educational philosophy, the curriculum takes on a distinctive approach. It is designed to provide students with real-world experiences that are meaningful, relevant, and applicable to their everyday lives. Rather than focusing solely on rigid subject-matter content, the progressive curriculum aims to engage students in real-world problem-solving activities, fostering critical thinking and practical skills. This section will delve into two key aspects of the progressive curriculum: real-world problem-solving and relevance to everyday life.

Real-World Problem-Solving

One of the core tenets of progressivism is the belief that education should be a process of ongoing growth, centered on the needs, experiences, interests, and abilities of students. In line with this philosophy, the progressive curriculum emphasizes real-world problem-solving activities. Students are encouraged to tackle authentic challenges that mirror situations they may encounter outside of the classroom. This approach not only enhances their critical thinking abilities but also equips them with valuable skills for navigating the complexities of the real world.

By engaging students in real-world problem-solving, the progressive curriculum promotes active learning and encourages students to apply their knowledge and skills to practical situations. This hands-on approach fosters a deeper understanding of concepts and helps students develop problem-solving strategies that can be transferred to various contexts.

Relevance to Everyday Life

Another fundamental aspect of the progressive curriculum is its emphasis on relevance to everyday life. Progressive educators believe that education should connect with students' existing knowledge, experiences, and interests. The curriculum is designed to link all aspects of study to students' everyday life experiences, making the learning process personally meaningful and applicable.

By incorporating topics and activities that are relevant to students' lives, the progressive curriculum promotes engagement and motivation. Students are more likely to be interested and invested in their learning when they can see the direct connection between what they are studying and their own experiences. This relevancy helps students recognize the practical value of their education, fostering a sense of purpose and meaning.

In the progressive classroom, the curriculum is not confined to traditional subjects but extends beyond them to encompass real-life issues and interdisciplinary topics. This interdisciplinary approach allows students to make connections across different fields of knowledge, enabling them to develop a holistic understanding of the world and its complexities.

By emphasizing real-world problem-solving and relevance to everyday life, the progressive curriculum aims to prepare students for active participation in society. It equips them with the skills, knowledge, and mindset needed to navigate the challenges and complexities of the world beyond the classroom. Through this approach, students develop a sense of agency, critical thinking abilities, and a deep understanding of how their learning connects to the real world.

Progressive Teaching Methods

Progressive education philosophy emphasizes active learning, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills. In a progressive classroom, teachers employ various teaching methods to foster these skills and create an engaging learning environment. Two prominent teaching methods in progressivism are group work dynamics and project-based learning.

Group Work Dynamics

Group work dynamics play a significant role in progressive classrooms. Collaborative learning allows students to work together in small groups, promoting cooperation, communication, and teamwork. By engaging in group discussions and activities, students develop social skills and learn from their peers' diverse perspectives. This method encourages active participation, critical thinking, and the exchange of ideas.

Group work dynamics also provide opportunities for students to take ownership of their learning. By working collaboratively, students can collectively solve problems, analyze information, and make decisions. Teachers act as facilitators, guiding and supporting students as they navigate group dynamics and contribute to the learning process.

Project-Based Learning

Project-based learning (PBL) is another essential teaching method in progressive education. PBL involves students working on extended projects that require them to investigate real-world problems, analyze information, and develop solutions. This approach promotes active learning, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills.

Through project-based learning, students become active participants in their education. They take on roles as researchers, problem solvers, and creators, allowing them to apply knowledge and skills in meaningful ways. Projects are often interdisciplinary, integrating various subjects and encouraging students to make connections between different areas of knowledge.

Additionally, project-based learning fosters creativity and innovation. Students have the freedom to explore topics of interest, express their ideas, and present their findings in creative ways. This method encourages self-directed learning and helps students develop skills that are applicable beyond the classroom.

When implementing group work dynamics and project-based learning, teachers create an environment that supports student-centered learning. They provide guidance, structure, and resources while allowing students to take ownership of their learning journey. By incorporating these progressive teaching methods, educators can empower students to become active, critical thinkers and lifelong learners.

Role of the Teacher

In the context of progressivism in educational philosophy, the role of the teacher is redefined to foster a student-centered learning environment. The teacher acts as a facilitator and guide, directing the students' learning while also valuing and incorporating their voices. This approach emphasizes collaboration and decision-making, empowering students to take an active role in their education.

Facilitator and Guide

In a progressive classroom, the teacher assumes the role of a facilitator and guide. Rather than being the sole source of knowledge, the teacher helps students construct the skills they need to understand and process content. This involves creating a supportive and inclusive environment where students feel encouraged to explore and inquire. The teacher facilitates learning experiences that encourage critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity.

As a guide, the teacher provides structure and direction while fostering student autonomy. They offer guidance and support, helping students navigate through the learning process and acquire essential skills. By valuing the students' voice and ideas, the teacher cultivates a sense of ownership and responsibility for learning outcomes.

Collaboration and Decision-Making

Collaboration and decision-making are integral components of the teacher's role in a progressive classroom. The teacher actively collaborates with students, involving them in making group decisions that shape the learning experience. This collaborative approach promotes a sense of community and shared responsibility within the classroom.

By engaging students in decision-making, the teacher helps them understand the democratic values essential in society. Students learn to respect diverse perspectives, negotiate conflicts, and contribute to the collective decision-making process. This fosters a sense of agency and empowerment, as students recognize their ability to shape their educational journey.

Through collaboration and decision-making, the teacher creates a classroom environment that values open communication, active participation, and mutual respect. Students are encouraged to express their thoughts and ideas, leading to a more inclusive and enriching learning experience.

By embracing the role of a facilitator and guide, and fostering collaboration and decision-making, teachers in a progressive classroom empower students to take ownership of their education. This approach nurtures critical thinking, problem-solving, and the acquisition of democratic values, preparing students for active engagement in society.

Application in Modern Education

Progressivism in educational philosophy has had a significant impact on learning practices in modern education. By embracing the core tenets of progressivism and implementing progressive teaching methods, educators aim to create a dynamic and student-centered learning environment.

Impact on Learning Practices

In a progressive school environment, education is learner-centric, prioritizing individuality, change, and progress as fundamental aspects of a child's education. The focus is on tailoring the curriculum to meet the needs, experiences, interests, and abilities of students, making learning more relevant and engaging [3]. This approach encourages students to take an active role in their own learning, fostering curiosity, problem-solving skills, critical thinking, and character development.

Progressive education emphasizes hands-on learning experiences, where students are actively involved in the learning process. This approach, championed by influential educational philosopher John Dewey, promotes learning through real-world problem-solving rather than rote memorization. By engaging in practical, experiential learning activities, students are better equipped to apply their knowledge and skills to real-life scenarios.

Furthermore, progressive education emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary studies and thematic units. By integrating different subjects and connecting learning across disciplines, students gain a deeper understanding of concepts and their relevance to the world around them. This interdisciplinary approach helps students make connections between different areas of knowledge, fostering a holistic understanding of various topics.

Challenges and Adaptations

While progressivism has brought positive changes to modern education, there are challenges associated with its implementation. Despite the belief that progressivism dominates American education, traditional teaching and learning methods still prevail in many classrooms. Reasons for this include teacher-centered instruction, teacher-focused classroom management, the dominance of traditional school subjects in the curriculum, reliance on textbooks for curriculum delivery, and assessments based on memorization [3].

To fully embrace progressivism in education, teachers and schools must adapt their practices to create a truly learner-centered environment. This may involve implementing effective classroom management techniques that promote student engagement, collaboration, and active participation. It also requires a shift in assessment methods to focus on evaluating students' problem-solving abilities, critical thinking skills, and application of knowledge.

Additionally, teachers need to continuously update their instructional strategies to align with progressivist principles. This may involve incorporating project-based learning and group work dynamics into their teaching methods. By providing opportunities for students to collaborate, engage in hands-on activities, and take ownership of their learning, teachers can create an environment that fosters creativity, critical thinking, and 21st-century skills.

In conclusion, the application of progressivism in modern education has transformed learning practices by placing the learner at the center of the educational experience. By embracing hands-on learning, real-world problem-solving, and interdisciplinary approaches, educators strive to create an engaging and relevant learning environment. However, challenges remain in fully implementing progressivist principles, requiring ongoing adaptation and professional development for teachers to create effective and impactful learning experiences.

- [1]: https://kstatelibraries.pressbooks.pub

- [2]: https://www.siue.edu

- [3]: https://www.linkedin.com

18 minute read

Progressive Education

Philosophical foundations, pedagogical progressivism, administrative progressivism, life-adjustment progressivism.

Historians have debated whether a unified progressive reform movement existed during the decades surrounding the turn of the twentieth century. While some scholars have doubted the development of a cohesive progressive project, others have argued that while Progressive Era reformers did not march in lockstep, they did draw from a common reform discourse that connected their separate agendas in spirit, if not in kind. Despite these scholarly debates, historians of education have reached a consensus on the central importance of the Progressive Era and the educational reformers who shaped it during the early twentieth century. This is not to say that historians of education do not disagree–in fact, they disagree intensely–on the legacy of Progressive educational experiments. What they do agree on is that during the Progressive Era (1890–1919) the philosophical, pedagogical, and administrative underpinnings of what is, in the early twenty-first century, associated with modern schooling, coalesced and transformed, for better or worse, the trajectory of twentieth-century American education.

Philosophical Foundations

The Progressive education movement was an integral part of the early twentieth-century reform impulse directed toward the reconstruction of American democracy through social, as well as cultural, uplift. When done correctly, these reformers contended, education promised to ease the tensions created by the immense social, economic, and political turmoil wrought by the forces of modernity characteristic of fin-de-siècle America. In short, the altered landscape of American life, Progressive reformers believed, provided the school with a new opportunity–indeed, a new responsibility–to play a leading role in preparing American citizens for active civic participation in a democratic society.

John Dewey (1859–1952), who would later be remembered as the "father of Progressive education," was the most eloquent and arguably most influential figure in educational Progressivism. A noted philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer, Dewey graduated from the University of Vermont in 1879, taught high school briefly, and then earned his doctorate in philosophy at the newly formed Johns Hopkins University in 1884. Dewey taught at the University of Michigan from 1884 to 1888, the University of Minnesota from 1888 to 1889, again at Michigan from 1889 to 1894, then at the University of Chicago from 1894 to 1904, and, finally, at Columbia University from 1904 until his retirement in 1931.

During his long and distinguished career, Dewey generated over 1,000 books and articles on topics ranging from politics to art. For all his scholarly eclecticism, however, none of his work ever strayed too far from his primary intellectual interest: education. Through such works as The School and Society (1899), The Child and the Curriculum (1902), and Democracy and Education (1916), Dewey articulated a unique, indeed revolutionary, reformulation of educational theory and practice based upon the core relationship he believed existed between democratic life and education. Namely, Dewey's vision for the school was inextricably tied to his larger vision of the good society, wherein education–as a deliberately conducted practice of investigation, of problem solving, and of both personal and community growth–was the wellspring of democracy itself. Because each classroom represented a microcosm of the human relationships that constituted the larger community, Dewey believed that the school, as a "little democracy," could create a "more lovely society."

Dewey's emphasis on the importance of democratic relationships in the classroom setting necessarily shifted the focus of educational theory from the institution of the school to the needs of the school's students. This dramatic change in American pedagogy, however, was not alone the work of John Dewey. To be sure, Dewey's attraction to child-centered educational practices was shared by other Progressive educators and researchers–such as Ella Flagg Young (1845–1918), Dewey's colleague and kindred spirit at the University of Chicago, and Granville Stanley Hall (1844–1924), the iconoclastic Clark University psychologist and avowed leader of the child study movement–who collectively derived their understanding of child-centeredness from reading and studying a diverse array of nineteenth and twentieth-century European and American philosophical schools. In general, the received philosophical traditions employed by Dewey and his fellow Progressives at once deified childhood and advanced ideas of social and intellectual interdependence. First, in their writings about childhood, Frenchman Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) emphasized its organic and natural dimensions; while English literary romantics such as William Wordsworth (1770–1850) and William Blake (1757–1827) celebrated its innate purity and piety, a characterization later shared by American transcendentalist philosophers Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882) and Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862). For these thinkers, childhood was a period of innocence, goodness, and piety that was in every way morally superior to the polluted lives led by most adults. It was the very sanctity of childhood that convinced the romantics and transcendentalists that the idea of childhood should be preserved and cultivated through educational instruction.

Second, and more important, Dewey and his fellow educational Progressives drew from the work of the German philosopher Friedrich Froebel (1782–1852) and Swiss educator Johann Pestalozzi (1746–1827). Froebel and Pestalozzi were among the first to articulate the process of educating the "whole child," wherein learning moved beyond the subject matter and ultimately rested upon the needs and interests of the child. Tending to both the pupil's head and heart, they believed, was the real business of schooling, and they searched for an empirical and rational science of education that would incorporate these foundational principles. Froebel drew upon the garden metaphor of cultivating young children toward maturity, and he provided the European foundations for the late-nineteenth-century kindergarten movement in the United States. Similarly, Pestalozzi popularized the pedagogical method of object teaching, wherein a teacher began with an object related to the child's world in order to initiate the child into the world of the educator.

Finally, Dewey drew inspiration from the ideas of philosopher and psychologist William James (1842–1910). Dewey's interpretation of James's philosophical pragmatism, which was similar to the ideas underpinning Pestalozzi's object teaching, joined thinking and doing as two seamlessly connected halves of the learning process. By focusing on the relationship between thinking and doing, Dewey believed his educational philosophy could equip each child with the problem-solving skills required to overcome obstacles between a given and desired set of circumstances. According to Dewey, education was not simply a means to a future life, but instead represented a full life unto itself.

Taken together, then, these European and American philosophical traditions helped Progressives connect childhood and democracy with education: Children, if taught to understand the relationship between thinking and doing, would be fully equipped for active participation in a democratic society. It was for these reasons that the Progressive education movement broke from pedagogical traditionalists organized around the seemingly outmoded and antidemocratic ideas of drill, discipline, and didactic exercises.

Pedagogical Progressivism

The pedagogical Progressives who embraced this child-centered pedagogy favored education built upon an experience-based curriculum developed by both students and teachers. Teachers played a special role in the Progressive formulation for education as they merged their deep knowledge of, and affection for, children with the intellectual demands of the subject matter. Contrary to his detractors, then and now, Dewey, while admittedly antiauthoritarian, did not take child-centered curriculum and pedagogy to mean the complete abandonment of traditional subject matter or instructional guidance and control. In fact, Dewey criticized derivations of those theories that treated education as a mere source of amusement or as a justification for rotevocationalism. Rather, stirred by his desire to reaffirm American democracy, Dewey's time- and resource-exhaustive educational program depended on close student–teacher interactions that, Dewey argued, required nothing less than the utter reorganization of traditional subject matter.

Although the practice of pure Deweyism was rare, his educational ideas were implemented in private and public school systems alike. During his time as head of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Chicago (which also included the fields of psychology and pedagogy), Dewey and his wife Alice established a University Laboratory School. An institutional center for educational experimentation, the Lab School sought to make experience and hands-on learning the heart of the educational enterprise, and Dewey carved out a special place for teachers. Dewey was interested in obtaining psychological insight into the child's individual capacities and interests. Education was ultimately about growth, Dewey argued, and the school played a crucial role in creating an environment that was responsive to the child's interests and needs, and would allow the child to flourish.

Similarly, Colonel Francis W. Parker, a contemporary of Dewey and devout Emersonian, embraced an abiding respect for the beauty and wonder of nature, privileged the happiness of the individual over all else, and linked education and experience in pedagogical practice. During his time as superintendent of schools in Quincy, Massachusetts, and later as the head of the Cook Country Normal School in Chicago, Parker rejected discipline, authority, regimentation, and traditional pedagogical techniques and emphasized warmth, spontaneity, and the joy of learning. Both Dewey and Parker believed in learning by doing, arguing that genuine delight, rather than drudgery, should be the by-product of manual work. By linking the home and school, and viewing both as integral parts of a larger community, Progressive educators sought to create an educational environment wherein children could see that the hands-on work they did had some bearing on society.

While Progressive education has most often been associated with private independent schools such as Dewey's Laboratory School, Margaret Naumberg's Walden School, and Lincoln School of Teacher's College, Progressive ideas were also implemented in large school systems, the most well known being those in Winnetka, Illinois, and Gary, Indiana. Located some twenty miles north of Chicago on its affluent North Shore, the Winnetka schools, under the leadership of superintendent Carleton Washburne, rejected traditional classroom practice in favor of individualized instruction that let children learn at their own pace. Washburne and his staff in the Winnetka schools believed that all children had a right to be happy and live natural and full lives, and they yoked the needs of the individual to those of the community. They used the child's natural curiosity as the point of departure in the classroom and developed a teacher education program at the Graduate Teachers College of Winnetka to train teachers in this philosophy; in short, the Winnetka schools balanced Progressive ideals with basic skills and academic rigor.

Like the Winnetka schools, the Gary school system was another Progressive school system, led by superintendent William A. Wirt, who studied with Dewey at the University of Chicago. The Gary school system attracted national attention for its platoon and work-study-play systems, which increased the capacity of the schools at the same time that they allowed children to spend considerable time doing hands-on work in laboratories, shops, and on the playground. The schools also stayed open well into the evening hours and offered community-based adult education courses. In short, by focusing on learning-by-doing and adopting an educational program that focused on larger social and community needs, the Winnetka and Gary schools closely mirrored Dewey's own Progressive educational theories.

Administrative Progressivism

While Dewey was the most well known and influential Progressive educator and philosopher, he by no means represented all that Progressive education ultimately became. In the whirlwind of turn-of-the-century educational reform, the idea of educational Progressivism took on multiple, and often contradictory, definitions. Thus, at the same time that Dewey and his followers rejected traditional methods of instruction and developed a "new education" based on the interests and needs of the child, a new cadre of professionally trained school administrators likewise justified their own reforms in the name of Progressive education.

Administrative Progressives shared Dewey's distaste for nineteenth-century education, but they differed markedly with Dewey in their prescription for its reform: administrative Progressives wanted to overthrow "bookish" and rigid schooling by creating what they believed to be more useful, efficient, and centralized systems of public education based on vertically integrated bureaucracies, curricular differentiation, and mass testing.