Is gold mining part of the solution to climate change?

- Full Transcript

Subscribe to Foresight Africa Podcast

Subscribe to Africa in Focus

Foresight Africa Podcast

John Mulligan and John Mulligan Director and Climate Change Lead - World Gold Council Aloysius Uche Ordu Aloysius Uche Ordu Director - Africa Growth Initiative , Senior Fellow - Global Economy and Development , Africa Growth Initiative

August 16, 2023

- Gold mining companies should demonstrate their awareness of their impacts on society and local economies

- Responsible gold mining means working with civil society and consulting with governments

- We need to decarbonize mining, we need more minerals to allow us to decarbonize, and gold is part of that solution

- 34 min read

John Mulligan, climate change lead at the World Gold Council, talks with host Aloysius Ordu about the Council’s role in global gold markets, changes in those markets, and how gold mining can be part of the solution to climate change. Mulligan also looks ahead to the next global climate conference, COP28 in Dubai.

Artisanal and Small-scale Gold Mining , report from the World Gold Council.

“ Gold mining, climate change, and Africa’s transition ,” viewpoint in Foresight Africa 2023

- Subscribe and listen to Foresight Africa on Apple , Spotify , and wherever you listen to podcasts.

- Learn about other Brookings podcasts from the Brookings Podcast Network .

- Sign up for the podcasts newsletter for occasional updates on featured episodes and new shows.

- Send feedback email to [email protected] .

ORDU: I’m Aloysius Uche Ordu, director of the Africa Growth Initiative at the Brookings Institution, and this is Foresight Africa podcast.

Since 2011, the Africa Growth Initiative at Brookings has published a high-profile report entitled Foresight Africa . The report covers key events and trends likely to shape affairs in Africa in the year ahead. On this podcast, I engage with the report authors as well as policymakers, industry leaders, Africa’s youths, and other key figures. Learn more on our website, Brookings dot edu slash Foresight Africa podcast.

ORDU: My guest today is Mr. John Mulligan. John is the director and climate change lead at the London-based World Gold Council, where he’s been working for the last two decades. John, a our warm welcome to our show.

MULLIGAN: Thank you and thanks for having me. It’s great to be here.

ORDU: Let’s get started then. You serve as the director, as I mentioned earlier, and climate change lead at the World Gold Council. For the benefit of our listeners in Africa and elsewhere in the world, what exactly does the council do?

MULLIGAN: It’s a very good question. We were formed 35 years ago now by some of the large gold mining companies in the world who at the time, I think it’s fair to say, felt that they were somewhat disconnected from the gold markets. And that’s because in most of the world, it’s quite a long way from where gold is mined to where it’s consumed, with the exception of China. So there was a sense that what was happening in the markets was not well understood by the people producing gold. So they formed an organization called the World Gold Council to try and bridge that gap, to try and perhaps wherever possible contribute to what we call market development, to broadening the market, broadening accessibility to gold.

What’s happened over the last few decades is how we do that, how we implement our mandate, has very much changed. For the first two decades, we were probably very focused in the markets, developing investment markets, talking to regulators, developing product lines. But increasingly, I think, it’s become recognized that we have to look at the whole value chain and we have to look at that value chain to ensure that the product and the way it’s produced is both fit for purpose but also, if possible, minimizes negative impacts and maximizes value creation.

So, my role I started off as an investment and analysis, but over the last decade or so, I’ve also started to look at those the how we intervene or influence the value chain in terms of sustainability and what we now call ESG, environmental, social, and governance risks and opportunities.

ORDU: We’ll talk some more about this in a minute. And I just wondered, in the time you’ve been there, as you mentioned, over two decades or so, I know it’s impossible to capture all the things you’ve accomplished, but could you share with us just a few highlights?

MULLIGAN: There’s been some structural changes in the market. So first of all, there was concentration in gold production. If we were talking about the seventies and early eighties, South Africa still dominated go mining to some extent. It was certainly less distributed across the world in terms of where gold came from.

But when it comes to the destinations for gold—how gold is bought, how it’s consumed—that’s quite significant, and the World Gold Council has been, I think it’s fair to say, instrumental in opening up a lot of markets. We were very involved in opening up the Chinese market, for instance. It was illegal until the early 2000s for Chinese individuals to own gold as an investment. So it was a very small market. It was a very heavily controlled market. It is now the largest gold market in the world. Similarly, we were involved in opening up the Indian market.

And it’s quite significant that the opening up of the gold markets, whilst not causal, was quite concurrent with the broader development of those markets. And that’s true generally. So they were very significant cause they created structural change in the market.

Other structural changes have been introducing institutional investment to gold. So initially when the gold market started to open up in the seventies and eighties, big institutional investors didn’t really consider investing in gold at all. And even if they did, they weren’t sure how to. We created products and with the financial markets created efficient mechanisms. So they are very big structural changes in terms of the global gold market.

And I think in terms of how gold is produced and with a significant impact on the African context, basically firming up what we call responsible gold mining, saying, okay, how does how does the mining companies, how do they demonstrate both responsible practice but also how do they demonstrate that they are aware of their wider impacts in terms of society and local economies? And that’s been a gradual change, but over the last four or five years we’ve seen a real concerted effort to demonstrate that awareness of those impacts.

ORDU: Central banks are buying gold in unprecedented volumes given it’s the risk mitigation asset, as you know. Can you tell us about how your work is enabling central banks to become more sustainable?

MULLIGAN: So we have we’ve had a central bank policy and engagement team for many, many years. One of the things was literally just to make sure that central banks, particularly in developing economies that generally didn’t participate in gold, demonstrating to them the benefits of gold, meaning basically how they can diversify their reserve asset management systems and move away from concentration risk in one set or one currency based set of investments.

But also, more recently, we’ve been involved in bringing central banks to the table to discuss how they may possibly participate to the benefit of their local gold market. And what I mean by that is we, the board, our members, are the large scale miners to some of the industrialized miners. However, we’re very mindful that in a lot of developing and frontier economies, artisanal gold mining is both a major employer but also a potentially a major risk factor. It can generate a lot of jobs, relatively well-paying jobs, but they can come without much regulation. They can come often with very significant social and environmental risks.

And so one of the things we’ve done quite recently with the central banks is say those central banks that are aware of their local gold mining, aware of the artisanal gold production, they may be a potentially a force for good, a force by which they can have purchasing programs that encourage what we call formalization or more responsible practices in the host country, but also allow the local gold miner to have an access point to the international markets. And that’s one of the great challenges. Often local gold miners, artisanal gold miners, don’t have any clear route to fair market.

So it’s a relatively small program within the central bank scheme of our broader operations. But I think it is quite significant when we start to talk about gold mining in the African context.

ORDU: In 2019, I believe the World Gold Council launched the Responsible Gold Mining Principles. Could you explain what these principles are, briefly to us, please?

MULLIGAN: I can and I’m very glad you asked, because we for a long time, ever since I’ve been here, have been talking about responsible gold. When we’re talking about responsible, we’re talking about the gold market, we’re talking about responsible gold actors, responsible gold production.

But increasingly, over the last five years or so and maybe the last decade, there’s a lot greater scrutiny, a lot more questions asked—so what do you mean by that and how can you demonstrate it? So being aware of both societal expectations—civil society expectations and investor expectations—we said, okay, well, we need to define what we mean by this in detail, because we have almost a privileged access to a large group of gold producers, our members. We basically said working with them, working with civil society, working with many organizations in consultation with governments, et cetera, we will define what we mean by responsible gold mining. That became the responsible gold mining principles.

There are ten overarching principles which we think represent most of the material aspects and risks that we book it into kind of ESG. Actually, we start with G, we start with governance, and work down towards impact. And underneath those ten umbrella principles, there are 51 principles. They are, wherever possible, independently verified by external assurers. They are now mandatory for our membership. And our membership is well over half of all of corporate gold production in the world. So that means that by being mandatory, by being independently verified, we have made it quite clear what we perceive as both the expectations of gold mining, but also what their performance will look like and how they will demonstrate it that can be scrutinized by society and investors and other stakeholders.

So that’s what the RGMPs are for. We’re just coming towards the end of the first full reporting cycle. So the idea was to give the companies three years to get up to speed if they needed to before they started reporting publicly. Then reporting becomes an annual process in terms of verification and assurance. We’re coming to the end of that first cycle, which like I say, it was launched in 2019, started to become implemented in 2020, and now we’re looking for that reporting cycle to kick in very soon.

ORDU: So Africa, as you know, holds considerable resources vital to a clean energy future. The potentials to transform economic growth and to create jobs are huge for the continent. How do we ensure that Africa’s role in the global decarbonization journey is broadened beyond mineral extraction?

MULLIGAN: It’s a very good question. And I should contextualize that by the fact that the discussion around critical minerals and minerals that are needed to underpin the clean energy infrastructure, clean technology, renewable energy, et cetera, gold is not included in those. And I should make that really clear: gold is not seen as a critical mineral.

That said, it has some very critical roles to play when we talk about the gold value chain. And that is because gold in many remote locations and in many African contexts has to generate its own power. It has to generate its own power because there is no grid to plug into. And therefore if it is to decarbonize, it needs to bring clean energy infrastructure technology to those areas. And in doing so, the opportunities to then make some of that energy more widely available to communities. So you start to make local and clean energy transition technology available and economically viable to local economies. And I think that’s key.

However, to your broader question, I think the question is, and it’s one that we hear often in mining, how do you create a sustainable supply chain? How do you basically ensure that mining can not only commence and start to produce those minerals? How can the extraction of those minerals generate value that is shared by the host country or the host community?

Now, we spend a lot of time on this in gold mining because gold is of high value. There’s often a perception that the gold mining process extracts the mineral and extracts the majority of the value. We have spent over a decade now, again, and because of that privileged position of being able to ask the miners, we would like to know where the money goes. We’d like to track the money. Follow the money when it goes. Where do you spend your money in terms of taxes, royalties, suppliers, the income levels of your employees, et cetera? Where does the money go? And then how much money comes back to lenders of capital and shareholders, et cetera.

And certainly the vast majority over the last decade, it depends on where the gold market is, but typically between 60 and 80% of the money expended in gold mining actually remains in host countries. Most significantly, which often people often underestimate, is the significance of the money that goes to local employees and suppliers, providers. There has been a major effort over the last decade to encourage local supply chains to grow, to try and develop economic capacity.

The vast majority of employees, for instance, it’s no longer an expat industry. The vast majority of employees are 95% or more are typically employed from the host country. And I think that’s key.

What we’re seeing that’s also significant, and I think it’s true of all mining, but it’s one thing that the mining industry needs to communicate to its host countries and host governments, and it’s really important when we talk about the transition, is the shift in technologies, the shift in the nature of mining, and the shift in skill sets and opportunities.

Yes, it’s certainly a heavy industry. Yes, it involves a lot of hard labor, but increasingly it’s a high technology industry. Increasingly, those skills are transferable and I think that needs to be developed and far better explained to both host policymakers and stakeholders, because I think that allows—I’m talking about the gold market and gold in the gold mining industry—but it allows the broader industry to try and demonstrate its value and its broader purpose, which I think is not well communicated.

ORDU: Talking of supply chains, John, earlier this year you attended the OECD Responsible Minerals Forum in Paris. Governments worldwide, as you know, are seeking to build more secure supply chains. How can firms and governments work together to support more responsible practices? And do you have any examples of what has worked well in African countries, please?

MULLIGAN: It’s a very good question indeed and very topical. That forum on Responsible Sourcing of Minerals, it emerged from trying to create responsible minerals supply chains in the context in the context of potentially conflict affected areas. That’s what that policy grew out of. It’s now broadened its mandate to look at responsible mineral chains across the board. The question that most comes most comes up in that forum, the question that’s often the one that is seen as key to unlocking collaboration and potential, a question that is not always well answered is how to bring governments to the table in a collaborative way for a sustained period.

And I mentioned that sustained period because you mentioned some of the success stories. The problem with the success stories if they are not funded with a long-term view supported by the government—so they may be funded by development institutions or some development finance, but it’s relatively short-term—is the success story can be a success story for a while and it can cease to be when the funding stops or the development institution removes itself.

You need that long-term vision and long-term commitment from a group of actors, frankly, from business. Business often brings the capabilities, the capacity, some of the technologies, the skill sets. It also sometimes takes the risk particularly when we’re talking about new technologies and so on. And I think it sometimes can do that. Development banks often come in and may be taking some of that risk too, in terms of the initial stage of projects.

But I think what we really need, and I think what’s been perhaps lacking in the past, is the long term vision in terms of, okay, what is the joint objective of both corporate actors and governments? So there are some success stories, but the success stories have also often turned into failures, and so I’m hesitant to point them out. We were talking about them. And in the artisanal space, we’ve been looking at that really closely, saying, okay, well, how can large scale gold miners, along with international, supranational organizations and governments, come together to try and avoid those success stories that have failed and that have turned to failure in the past?

The World Gold Council is talking with organizations like the World Bank and so on to try and see how we might define what good practice looks like, find solutions, and find solutions that are enduring. That’s the real challenge.

ORDU: A key challenge indeed. John, you also you led an excellent report last year called “Lessons learned on managing the interface between the large scale and artisanal and small scale mining.” What were your key findings? And what’s the status of implementation of that report?

MULLIGAN: So I’ve already alluded to it. When I was fudging the answer to your previous question, I was actually alluding to some of the some of the content, some of the content in that report. And I can’t claim the glory for that report. Several of my colleagues, and particularly one called Edward Bickham, was very key in drafting that.

I think where it is now is when we published that, we’d already published the central bank case studies example of how central banks might intervene in terms of artisanal gold mining. So if you look at that report you mention, it covered a whole load of examples of what we might call attempts at good practice, potential solutions, both often initiated by large scale miners and pointed out where there had been some successes. As I say, a lot of those successes have not been enduring. Where we are now is trying to say, okay, well, what have we learned from bringing those lessons together?

And one of them has been, okay, well, can we find ways to incentivize government to come to the table at governments? So that’s a key. So one of the discussions with organizations like the World Bank is s their leverage from their perspective or in a collaboration to say, okay, well, let’s have a longer term perspectives on these projects. And so we are looking at those projects and engagement. We’ve got study groups and working groups where we’re trying to bring particular examples we can go back to in terms of good practice. It’s a little early for me to actually point to any specific project because frankly, we have just convened that group. We’ve had a number of meetings between state representatives, supernationals, mining companies in particular, gold miners in particular, many of whom are very, very eager to try and find a way to make this work.

There are some there are some examples of ASM mines working in corridors where they’ve been granted safe and secure tenure to develop and so on. But the real question is finding solutions that are scalable. The reason why they’re hesitating to highlight success stories is that a success story can almost overwhelm itself, meaning a number of artisanal miners can very much be given a secure, stable environment in which to operate. But if that becomes well-known, then you can have migration of larger numbers of people seeking similar opportunities, which frankly can overwhelm projects.

So that’s why I’m kind of saying you need to find success. You need to find the capacity to scale that success and it will always need governments to come to the table at some level.

ORDU: Fair enough. John, in response to a Bloomberg piece, you recently posted a message on LinkedIn that it is well worth repeating and very frequently that protecting nature is going to be expensive, but far less expensive than our destructive tendencies not to. Could you explain what you mean by that for the benefit of our listeners?

MULLIGAN: I’m first of all, I’m impressed somebody reads my LinkedIn page, so thank you for that. So often, and it’s true with climate and that’s kind of my specialization, but increasingly we’re looking at the broader what I call climate biodiversity intersections, because you need nature based solutions, you need to protect nature if we’re going to actually stabilize the climate, too. And the Bloomberg piece was useful because it put a number on what the annual cost will be to do this if we want to meet our nature protection, biodiversity protection goals. And I say that 1 trillion annual cost is seems very significant.

But the other big important thing is to put a cost on, as I say, cost of inaction, the cost of the cost of environmental degradation. And there’s a lot of time and effort now being put on trying to quantify the value of nature from an economic perspective. A lot of our economic activity’s underpinned by nature. Without it, we cannot do an awful lot of business. And so there’s an economic cost to inaction. And the economic cost, I think, was nearer 3 trillion if we don’t over time. So meaning that it there’s a net benefit, a net economic gain to biodiversity protection. This is not just about protecting the natural environment for us to enjoy at a kind of esthetical or a personal level. It is actually there are numbers to for hard-nosed business people and investment people to consider if they don’t reallocate capital or start building plans.

And so I think that once we got once we got numbers that basically start to make this real for investment folk, strategy makers who are also very focused on protecting economic opportunity, then I think it becomes meaningful for everybody. And the price of inaction is often something we fail to cost in it in terms of both valuations and our long-term estimates of economic growth and social development. So yeah, the cost of inaction, I think putting a number on it, it crystallizes the issue for many people.

ORDU: Those are those are no the numbers you mentioned, those are staggering numbers indeed. And yeah, it’s astounding. John, I recall earlier this year that you also you attended the Mining Indaba in Cape Town. In fact, we spoke while you were still there in Cape Town, South Africa. What were the key highlights and conclusions from the Indaba, what’s your take on the mining sector’s progress so far in terms of decarbonization? And what are some of the quick wins that can be made?

MULLIGAN: An immediate take away from the Indaba and from frankly a lot of the mining events I’ve attended, is that everybody now recognizes that mining is absolutely a core part of the solution to climate change. So this idea of the volume of critical minerals that will be needed to enable us to decarbonize is very significant. So we need to create a virtuous circle, meaning we need more mining, but we need to minimize negative impacts. And actually, as I say, maximize the positive.

Meanwhile, mining itself has to decarbonize because what is the point of producing more metals for decarbonization if you’re also pumping more carbon into the atmosphere? So we need decarbonize mining, we need more of these minerals, and very significantly I think that is now recognized. And so you have a sense of optimism to some extent in the mining community because they know that there is this significant demand for their material and therefore the industry should be in a good state to consider growth. Growth, hopefully, as I say, with a very clear sighted perspective on minimizing negative impacts.

But in terms of the state of decarbonization, well, there’s a lot to be optimistic about and I obviously know the mining industry best and the gold mining industry’s path to decarbonization—the low hanging fruit, the ability for it to decarbonize at speed and scale is, as I’ve mentioned before, an energy story. It is both the energy story, its ability to shift where it generates its own power from diesel and heavy fuel oil in particular to renewables. And also where it’s plugged into a grid, its ability to influence either the grid provider, the provider of the electricity, or to influence the policy environment to allow renewables to prosper.

And the example I always mentioned there is South Africa, where all industry pretty much was dependent on Eskom. It was a monopoly and it’s largely coal fired and therefore a very high carbon source of energy. And it was the precious metals, not solely, but the precious metals miners in particular who had long been trying to pressurize the government to say we need to be able to self-generate or to move away from Eskom if Eskom doesn’t move quickly enough. We have to and you have to allow us to do that.

So the removal of the cap, the limit on how industry could self-generate power, allowed in South Africa a renewable energy industry to prosper. It would have been economically unviable for renewable to prosper at scale because frankly the Eskom monopoly inhibited it. But I think that’s changed. I was in South Africa down a deep mine, one of the deepest in the world, and you come up to the surface and there is a brand new solar array and that solar array is already growing its capacity. So they had the ability to both self-generate to influence energy systems, I think that’s a major opportunity for go mining.

And it’s not just in developing economies. You see the great success stories in gold mining in parts of remote parts of Australia where renewables are now powering mines to the point that the majority of power in some mines is now renewables.

I think the mining industry has to both articulate its purpose in terms of how the host countries will benefit from that and it also has to support the building of capacity and infrastructure. And this is what the downside or the negative that I took away from Indaba was some of the conversations in the ministerial forums that I participated in where there was still a quite understandable, completely rational need to prioritize energy poverty. We said, okay, well let us use whatever resources we’ve got to address that first before we look at the issue of decarbonization.

I think if an industry, and gold mining is fortunate to be in this position, if an industry is a strategic contributor to the to a host economy, it may also have a strategic role in expanding the capacity of that country to embrace renewables. And I think that’s quite a key point. It does hopefully go back to your previous question about the possible role or opportunities for government and business to collaborate.

ORDU: Yeah. In fact, for the benefit of our listeners, I’ll turn now to John, your brilliant essay in Foresight Africa 2023 titled “Gold mining, climate change, and Africa’s transition.” Many, many, many of the issues we’re discussing here and the points you’ve made basically are well captured, succinctly captured, in that brilliant essay. In particular, you also wrote about how gold mining can be of strategic importance in catalyzing positive change, which you just spoke about now, especially when we consider the urgent need to mitigate climate change’s destructive impacts via rapid decarbonization. Can you explain a bit more, John, on how gold mining companies in Africa are contributing to this lower carbon footprint? In addition to the South Africa example you already cited?

MULLIGAN: So if you look in many countries in Africa and you look for the first mover, who brought and proved the viability of a renewable energy source, in many countries it is gold mining. So in Burkina Faso, the largest solar array is at the Essakane Project, which is a JV between the mine and the local government. That’s the largest solar array in that country. There is one in the planning stage, which is another gold mining company seeking to also build a substantial solar array.

If you look at hydropower in DRC, Kibali is a great story. Kibali was an artisanal gold mining area with an old dam I think that was left from the Belgian colonial times. That hydro dam has been developed. There have been now three additional hydro dams have been developed proving that the clean energy can be expanded.

But really interesting for me is that the people who built those dams gradually became a local business. So the last dam was actually somebody from the area. And that that business is now trying seeking to export those skills, the ability to build hydro power to other African nations. So it’s not only the ability to bring the technology to a country where basically there may be no capacity, there may be no frankly, maybe no political will to actually create a renewable project at scale, or at least not to absorb the risk that may be seen or perceived in such projects. But by doing so, I think gold miners have proved it, and then they create the capacity which could expand.

And as I mentioned, the great example of somebody who started work at one of those hydro dams many years ago and now owns a business which is actually exporting its abilities potentially to other African nations. I think that’s quite significant.

ORDU: John, you participated in COP27, Africa’s COP, in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt. What were you expectations going in and where those expectations met?

MULLIGAN: The COP question is always a good one. I have never heard this answered in any other way but half empty, half full. So the question with COP is the road to COP is often more significant than COP itself, because the road to COP is where the negotiations start, where the expectations are set. The positives, and there were some, I think, well, first of all we have seen in recent cops the very significant participation of business and investment. So COPs historically have often been governments haggling over their contributions and their targets and so on. And that’s still obviously core to what a COP is under the UNFCCC.

But nonetheless, we’ve seen business investors now coming to COP to try and accelerate progress and discuss reallocation of capital—I think that’s really quite significant—to hopefully support what governments have committed to. And so I think that was something that’s useful to see at COP. The biodiversity agreement which came out of COP was quite key. I know there’s the biodiversity came out to the biodiversity conference, which was not the same COP, but there was a lot of discussion of the overlap and a lot of momentum was set in terms of we need to address both at once.

I think there has been some clarity now in terms of decarbonization and movement away from fossil fuels. It emerged from Glasgow, but it’s kind of consolidated, we hope it’s consolidated. So I think there’s a lot to be said of what comes out of COP. And very significantly from an African-hosted COP, the issue of commitments to aid, adaptation, and resilience, which had often been neglected at COP, it had often been net zero decarbonization.

But this issue of the people who are unfortunately enduring the lived experience of climate change, the people who are enduring some of those really hard physical impacts, they need clear assistance in building resilience and adapting to those physical impacts. And that’s always been there since Paris, but it’s never really been given the time and the attention it needed to say, okay, how do we translate that? There’s always been some money potentially on the table. In fact, there’s been some money promised, but it wasn’t really addressed properly in this COP. I expect it to also be addressed in the UAE in the next COP.

So I think this issue of balancing the needs to decarbonize at scale and speed with this also pressing issue of building adaptation for the most vulnerable, I think that’s something which we expect that too to become a completely balanced argument because this whole issue of a just transition and has to be clarified. For many, the just transition seems to be climate change was not our fault historically, and therefore why should we decarbonize? Why can we not exploit our fossil fuel reserves? And there’s a logic to that. There’s a fairness to that.

At the same time, we’re all in this together. We all have to decarbonize. So we have to make sure that the COP discussion embraces that balance between rapid decarbonization and the ability to fund adaptation and resilience. And I think the conversations around COP, if I was to be positive, they seem to be a little more balanced in recent years.

ORDU: That certainly came across in Sharm el-Sheikh. You mentioned UAE, I’m just wondering, John, as we approach COP28, now billed the investment COP in Dubai and later this year, how is the Gold Council preparing for this COP?

MULLIGAN: It’s something that’s very high on my agenda, as you can imagine. First of all, as the question is, there is only a point in being at a COP if you have something to say. There’s thousands and thousands of people all talking at the same time, a COP. And so you have to bring something to the table. And for me, it is this idea of trying to create a rounded solution or position when it comes to climate risks. So we’ve, we looked recently at physical risk. We looked at adaptation resilience in terms of what that means at the gold mine site, but also what it might mean to wider communities particularly in vulnerable locations.

I think this issue of starting to consider nature and broader environmental impacts is also now key, which is what I’m kind of looking at and trying to see how that discussion is developing at COP. It’s certainly developing as we move towards COP. There’s not a climate event I’ve been to recently, should I say, that hasn’t been 30, 40% now a nature-biodiversity discussion. So, I’m interested in that.

The investment side is really interesting. As I say, we have seen very significant discussions. We saw in Glasgow the emergence of GFANZ, which we’ve seen these big institutional investor clusters who are all committing to both limiting their exposure to carbon intense assets but also facilitating and decarbonization in terms of asset allocation, where the money goes.

I think you would hope, given the fact this is billed as an investment COP, that that that conversation is comes to the fore. But really importantly, I think it needs to start joining up the investor perspective with the governmental perspective. And that’s kind of what’s often missing. Where do the government’s nationally determined contributions—what a government has said it will do about carbon, its commitments, its commitments emerging from Paris and restated successive COPs—how does that interact? How does it engage and hopefully be mutually supportive of corporate action and corporate finance and so on. And I think that conversation, the two are often parallel, but hopefully we can bring them together. If you have something called an investment COP, that’s what we would hope it would be for.

ORDU: Appropriately termed: investment, we do hope what materializes is what you just articulated. So, John, as we wind up, what advice I’m just wondering here, would you give Africa’s negotiators and policymakers on how best to prepare to achieve a better outcome for the continent in COP28?

MULLIGAN: A little small, simple question to end on, thank you. I think there’s a number of things which anybody who’s been kind of engaged in the climate change discussion cannot avoid. And yet constantly it’s disappointing when you see some of the discussions in practice. One, you need long-term vision. You need long-term strategy. These are objectives and problems that need us to look to a longer term than the next quarter, the next year, or even the next ten year of a particular political regime. So you need to consider what is good for the national interest, but what is good for the planet over the long term.

And what that means it’s in some points, I would say, greater collaboration. So in the African context, for instance, there’s lots of examples of how if countries—and again I’ll return back to decarbonization—if countries sought to complement each other’s natural resources, and by this I mean the sunshine, the wind, the water, and pool resources to be more complementary, they would have both more stable power systems and more affordable power systems.

You need some of those discussions regarding a kind of a regional interest. By region, I mean obviously very large regions, many countries talking to each other to try and achieve a long term objective. So it’s a long, long answer. But long term is absolutely key to this, I think. Courage and bravery to put the interests of people beyond the immediate political interests of the party or even a short term agenda, I think, is important. And unfortunately, that sometimes gets lost in the very the very understandable, rational, short-term problems that basically are obviously high on the agenda of many policymakers.

But as I say, these problems are so these problems are so large that, frankly, any one government would not solve them. You have to basically collaborate. And we’ve already mentioned it: basically, you need to bring responsible actors, investors into the fold, create amenable, stable environments to allow to allow value to be both created and distributed in a stable, long-term fashion. And I think that stability, that long term view is key.

ORDU: So I’ve been speaking to John Mulligan. He’s the director and climate change lead at the London-based World Gold Council. John, it’s been a pleasure speaking to you this morning. Thank you very much for joining our podcast.

MULLIGAN: Thank you again. It’s been delightful.

ORDU: I’m Aloysius Uche Ordu, and this has been Foresight Africa. To learn more about what you just heard today, you can find this episode online at Brookings dot edu slash Foresight Africa podcast.

The Foresight Africa podcast is brought to you by the Brookings Podcast Network. Send your feedback and questions to podcasts at Brookings dot edu. My special thanks to the production team, including Kuwilileni Hauwanga, supervising producer; Fred Dews, producer; Nicole Ntunigre and Sakina Djantchiemo, associate producers; and Gastón Reboredo, audio engineer.

The show’s art was designed by Shavanthi Mendis based on the concept by the creative from Blossom. Additional support for this podcast comes from my colleagues at Brookings Global and the Office of Communications at Brookings.

South Africa West Africa

Global Economy and Development

South Africa Sub-Saharan Africa West Africa

Africa Growth Initiative

Francis Mangeni, Andrew Mold, Landry Signé

October 2, 2024

Emily Gustafsson-Wright, Elyse Painter

September 25, 2024

Ian Seyal, Greg Wright

September 20, 2024

Families on the front lines of mining, drilling, and fracking need your help. Support them now!

Get Updates

Thanks for signing up!

Environmental Impacts of Gold Mining

Most consumers don’t know where the gold in their products comes from, or how it is mined. Gold mining is one of the most destructive industries in the world . It can displace communities, contaminate drinking water, hurt workers, and destroy pristine environments. It pollutes water and land with mercury and cyanide, endangering the health of people and ecosystems. Producing gold for one wedding ring alone generates 20 tons of waste .

Poisoned Waters

Gold mining can have devastating effects on nearby water resources. Toxic mine waste contains as many as three dozen dangerous chemicals including:

- petroleum byproducts

Mining companies around the world routinely dump toxic waste into rivers, lakes, streams and oceans – our research has shown 180 million tonnes of such waste annually. But even if they do not, such toxins often contaminate waterways when infrastructure such as tailings dams, which holds mine waste, fail.

According to the UNEP there have been over 221 major tailings dam failures. These have killed hundreds of people around the world, displaced thousands and contaminated the drinking water of millions.

The resulting contaminated water is called acid mine drainage, a toxic cocktail uniquely destructive to aquatic life. According to one study: “The effects of AMD are so multifarious that community structure collapses rapidly and totally, even though very often no single pollutant on its own would have caused such a severe ecological impact.”

These same “multifarious impacts” also makes recovery from such wastes much more difficult.

This environmental damage ultimately affects us — in addition to drinking water contamination, AMD’s byproducts such as mercury and heavy metals work their way into the food chain and sicken people and animals for generations.

The Biggest Polluters:

The top four mines that dump tailings into bodies of water account for 86% of the 180 million tonnes dumped into bodies of water each year. Those mines are:

- Freeport McMoRan and Rio Tinto’s Grasberg mine in West Papua, Indonesia, which accounts for approximately 80 million tonnes of tailings

- Newmont Sumitomo Mining’s Batu Hijau mine in Indonesia, which accounts for approximately 40 million tonnes

- Ok Tedi Mining Ltd.’s Ok Tedi mine in Papua New Guinea, which accounts for approximately 22 million tonnes

- Cliff’s Mining Company’s Wabush/Scully mine in Labrador, Canada, which accounts for 13 million tonnes of tailings

Of the over 2,000 major mining companies in the world only one company, BHP Billiton, is taking steps to avoid catastrophes like this from recurring.

For More Information

- Earthworks Ruined Lands, Poisoned Waters. A section from Dirty Metals: Mining Communities and the Environment .

- Earthworks Troubled Waters: How Mine Waste Dumping is Poisoning Our Oceans, Rivers, and Lakes

- Earthworks EARTHblog: Report from the field: Tailings dam fails at silver mine in Turkey

- Earthworks Cyanide Factsheet

- Earthworks Mining Pollutes the World’s Waterways

- Earthworks Acid Mine Drainage

- Earthworks Mercury

- Earthworks Fort Belknap Reservation

- Chronology of major tailings dam failures

- Earthworks EARTHblog: Troubled Waters – and no bridge to cross them

Solid Waste

Digging up ore displaces huge piles of earth and rock. Processing the ore to produce metals generates immense quantities of additional waste , as the amount of recoverable metal is a small fraction of the total ore mass. In fact, the manufacture of an average gold ring generates more than 20 tons of waste.

Heap Leaching

Many gold mines employ a process known as heap leaching , which includes dripping a cyanide solution through huge piles of ore. The solution strips away the gold and is collected in a pond, then run through an electro-chemical process to extract the gold.

This method of producing gold is cost effective but enormously wasteful: 99.99 percent of the heap becomes waste.

Gold mining areas are frequently studded with these immense, toxic piles. Some reach heights of 100 meters (over 300 feet), nearly the height of a 30-story building, and can take over entire mountainsides.

To cut costs, the heaps are often abandoned. Contaminated water, containing cyanide and other dangerous chemicals, can often contaminate groundwater and poison neighboring communities such as Miramar, Costa Rica .

Toxic Releases

Metal Mining was the number one toxic polluter in the United States in 2010. It is responsible for 1.5 billion pounds of chemical waste annualy- more than forty percent of all reported toxic releases. In 2010, metal mining released the following in the United States:

- over 200 million pounds of arsenic

- over 4 million pounds of mercury

- over 200 hundred million pounds of lead

Find who releases what in your part of the country by exploring the Environmental Protection Agency’s 2010 Toxic Release Inventory , or the web-based public-art project Superfund365 .

- Earthworks Cyanide Heap Leach Packet

- Earthworks Cyanide Fact Sheet

- EPA Mining Waste

- EPA Toxic Release Inventory EnviroFacts

- Brooke Singer’s web-based public-art project Superfund365

- Find user-friendly information from the Toxic Release Inventory at Scorecard.com

- Video on heap leaching proposed in Australia

- Earthworks Costa Rica | Puntarenas | Miramar : Glencairn Gold

- Earthworks Earthblog Costa Rican Gold Mine Suspended Due to Pollution Risks

Threatened Natural Areas

The mining industry has a long record of threatening natural areas, including officially protected areas.

Nearly three-quarters of active mines and exploration sites overlap with regions defined as of high conservation value. Mining is a major threat to biodiversity and to “frontier forest” (large tracts of relatively undisturbed forest).

The spotlighted mine sites below reveal the state of natural degradation caused by mining around the world:

The Grasberg Mine, Indonesia:

The Indonesian province of West Papua, which is the western half of the island of New Guinea, is home to Lorentz National Park , the largest protected area in Southeast Asia.

This 2.5 million-hectare expanse — about the size of Vermont — was declared a National Park in 1997 and a World Heritage site in 1999. But as early as 1973, Freeport-McMoRan Copper and Gold, Inc. , had begun chasing veins of gold through nearby formations.

This operation eventually led to the discovery of the world’s richest lode of gold and copper, lying close to the park boundary. The resulting open-pit mine, Grasberg, operated by its subsidiary PT Freeport Indonesia, has already:

- contaminated the coastal estuary and Arafura Sea and possibly the Lorentz National Park

- led to local violence and strikes

- dumped 110,000 tons of toxic mine tailings a day into the Ajikwa river

- triggered deadly landslide

The Grasberg mine is now visible from outer space . By the time it closes in 30 years, it will have excavated a 230 square-kilometer hole in the forest and produced over three billion tonnes of tailings.

Akyem Mine, Ghana:

After a contentious struggle with community protests, Newmont opened the Akyem mine in Ghana in 2007. This open-pit mine is the largest in Ghana and will destroy some 183 acres of protected forests.

Much of Ghana’s forested land has been denuded over the past 40 years. Less than 11 percent of the original forest cover remains. This biodiversity hotspot supports 83 species of birds, as well as threatened and endangered species such as Pohle’s fruit bat, Zenker’s fruit bat, and Pel’s flying squirrel.The forest reserves of Ghana are also extremely important for protecting many rare and threat- ened plant species.Many community members opposed construction of the Akyem mine, for its potential to contaminate freshwater and destroy the forests on which they depend. The mine is expected to begin operations in 2013.

Pebble Mine, US:

If developed, the Pebble Mine in Bristol Bay, Alaska, could be the largest mine in North America, covering over 15 square miles (39 square kilometers) of land and generating more than 3 billion tons of mine waste over its life.

The company proposes to withdraw more than 70 million gallons (265 million liters) of water per day, nearly three times the amount of water used in the city of Anchorage. This insatiable demand for water is a major threat to the Bristol Bay watershed, which supports the world’s largest sockeye salmon run and commercial sock- eye salmon fishery.116 Salmon, caribou, moose, and the many other fish and wildlife resources of the Bristol Bay watershed are also vital to the subsistence way of life of Alaska Native people, as well as key economic drivers in the state.

The Pebble Project and associated development are opposed by a strong and diverse constituency. The Alaska Inter-Tribal Council, a consortium of 231 federally recognized tribes in Alaska, and many tribal governments of the region have all passed resolutions against the project.119 Commercial salmon fishing businesses, premier Alaska hunting and fishing lodges, fishing and conservation groups, and the Alaska Wilderness Recreation and Tourism Association have expressed opposition, as has Alaska’s senior US senator, Ted Stevens.

Mining the Parks:

The UNESCO World Heritage Convention was designed to identify and protect areas around the world whose cultural and natural value is of “outstanding value to humanity.” Placement on the list requires requires extra protection for these special areas whose natural or cultural area extend far beyond local or national borders. Unfortunately, as detailed in our Dirty Metals report, mining companies have even encroached into these areas. Some of the special places that gold mining companies have encroached upon include:

- Okapi Wildlife Reserve, DRC

- Southeast Atlantic Forest Reserve, Brazil

- Sangay National Park, Ecuador

- Huascaran National Park, Peru

- Volcanoes of Kamatchhka, Russia

- Central Suriname NAture Reserve, Suriname

- Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda

- Kahuzi-Biega National Park, Congo

- Last Frontier Forests: Ecosystems and Economies on the Edge

- Description of New Guinea’s Lorentz National Park from UNESCO

- Condemnation of Freeport-McMoRan Copper and Gold, Public Eye People’s Award

- Report on the Grasberg Mine, “Below a Mountain of Wealth, a River of Waste.” New York Times 2005

- Report on a strike at the Grasberg Mine, “Indonesia strike hits Freeport’s Papua copper mine.” BBC 2011

- Report on deadly violence during the strike. “ Three dead at Papua Freeport mine, as strike continues.” BBC 2011

- Earthworks Troubled Waters

- NASA Earth Observatory ‘s picture of the Grasberg Mine from space

- A report of one of the massive landslides at the Grasberg Mine, “ Landslide leaves thousands stranded at Indonesia mine.” Rueters 2011

- World Heritage Sites in danger, “Mining threats on the rise in World Heritage sites.” IUCN 2011

Golden Rule

Ensure that projects are not located in protected areas, fragile ecosystems, or other areas of high conservation or ecological value.

Related Issues

Impacts of Dirty Gold on Communities

Impact of Metal Mining on Air Quality

Regulations on Cyanide Use in Gold Mining

Related blogs.

Timeline of Events at the QMM Mine in Madagascar

August 18, 2023

Victory at Last! EPA Employs Clean Water Act to Protect Alaska’s Bristol Bay from the Destructive Pebble Mine

January 31, 2023

EPA Announced New Plans to Protect Alaska’s Bristol Bay from Pebble Mine. So What’s Next?

June 08, 2022

Alaska’s Bristol Bay at risk from the Pebble Mine

June 24, 2016

Home » Gold » History of Gold

A brief history of gold uses, prospecting, mining and production

Republished from a usgs general interest publication by harold kirkemo, william l. newman, and roger p. ashley.

Egyptian gold: Artisans of ancient civilizations used gold lavishly in decorating tombs and temples, and gold objects made more than 5,000 years ago have been found in Egypt. Image copyright iStockphoto / Akhilesh Sharma.

Uses of Gold in the Ancient World

Gold was among the first metals to be mined because it commonly occurs in its native form, that is, not combined with other elements, because it is beautiful and imperishable, and because exquisite objects can be made from it. Artisans of ancient civilizations used gold lavishly in decorating tombs and temples, and gold objects made more than 5,000 years ago have been found in Egypt. Particularly noteworthy are the gold items discovered by Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon in 1922 in the tomb of Tutankhamun. This young pharaoh ruled Egypt in the 14th century B.C. An exhibit of some of these items, called "Treasures of Tutankhamun," attracted more than 6 million visitors in six cities during a tour of the United States in 1977-79.

The graves of nobles at the ancient Citadel of Mycenae near Nauplion, Greece, discovered by Heinrich Schliemann in 1876, yielded a great variety of gold figurines, masks, cups, diadems, and jewelry, plus hundreds of decorated beads and buttons. These elegant works of art were created by skilled craftsmen more than 3,500 years ago.

Ancient Gold Sources

The ancient civilizations appear to have obtained their supplies of gold from various deposits in the Middle East. Mines in the region of the Upper Nile near the Red Sea and in the Nubian Desert area supplied much of the gold used by the Egyptian pharaohs. When these mines could no longer meet their demands, deposits elsewhere, possibly in Yemen and southern Africa, were exploited.

Artisans in Mesopotamia and Palestine probably obtained their supplies from Egypt and Arabia. Recent studies of the Mahd adh Dhahab (meaning "Cradle of Gold") mine in the present Kingdom of Saudi Arabia reveal that gold , silver , and copper were recovered from this region during the reign of King Solomon (961-922 B.C.).

The gold in the Aztec and Inca treasuries of Mexico and Peru believed to have come from Colombia, although some undoubtedly was obtained from other sources. The Conquistadores plundered the treasuries of these civilizations during their explorations of the New World, and many gold and silver objects were melted and cast into coins and bars, destroying the priceless artifacts of the Indian culture.

Gold coin: As a highly valued metal, gold was used as a financial standard and has been used in coinage for thousands of years. United States ten dollar gold coin from 1850. Image copyright iStockphoto / Brandon Laufenberg.

Gold as a Medium of Exchange

Nations of the world today use gold as a medium of exchange in monetary transactions. A large part of the gold stocks of the United States is stored in the vault of the Fort Knox Bullion Depository. The Depository, located about 30 miles southwest of Louisville, Kentucky, is under the supervision of the Director of the Mint.

Gold in the Depository consists of bars about the size of ordinary building bricks (7 x 3 5/8 x 1 3/4 inches) that weigh about 27.5 pounds each (about 400 troy ounces; 1 troy ounce equals about 1.1 avoirdupois ounces.) They are stored without wrappings in the vault compartments.

Aside from monetary uses, gold, like silver, is used in jewelry and allied wares, electrical-electronic applications, dentistry, the aircraft-aerospace industry, the arts, and medical and chemical fields.

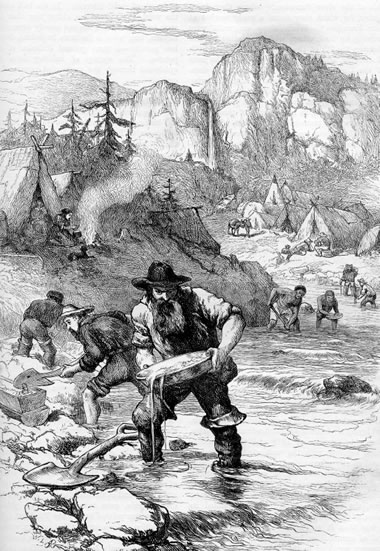

Gold rush: The discovery of gold triggered numerous gold rushes in the United States and around the world. Image copyright iStockphoto / Duncan Walker.

Gold Price Regulation and Variability

The changes in demand for gold and supply from domestic mines in the past two decades reflect price changes. After the United States deregulated gold in 1971, the price increased markedly, briefly reaching more than $800 per troy ounce in 1980. Since 1980, the price has remained in the range of $320 to $460 per troy ounce. The rapidly rising prices of the 1970's encouraged both experienced explorationists and amateur prospectors to renew their search for gold. As a result of their efforts, many new mines opened in the 1980's, accounting for much of the expansion of gold output. The sharp declines in consumption in 1974 and 1980 resulted from reduced demands for jewelry (the major use of fabricated gold) and investment products, which in turn reflected rapid price increases in those years.

Gold nuggets: Small nuggets of gold obtained by panning . Prospectors worked stream sediments to find tiny nuggets that they would sell or trade for supplies.

Properties of Gold

Gold is called a "noble" metal (an alchemistic term) because it does not oxidize under ordinary conditions. Its chemical symbol Au is derived from the Latin word "aurum." In pure form gold has a metallic luster and is sun yellow, but mixtures of other metals, such as silver , copper , nickel , platinum, palladium, tellurium, and iron, with gold create various color hues ranging from silver-white to green and orange-red.

Pure gold is relatively soft--it has about the hardness of a penny. It is the most malleable and ductile of metals. The specific gravity or density of pure gold is 19.3 compared to 14.0 for mercury and 11.4 for lead .

Impure gold, as it commonly occurs in deposits, has a density of 16 to 18, whereas the associated waste rock (gangue) has a density of about 2.5. The difference in density enables gold to be concentrated by gravity and permits the separation of gold from clay, silt, sand, and gravel by various agitating and collecting devices such as the gold pan , rocker, and sluicebox.

Nevada gold mine: Fortitude Mine in Nevada produced about 2 million ounces of gold from a lode deposit between 1984 and 1993. USGS image.

Gold Amalgam

Mercury (quicksilver) has a chemical affinity for gold. When mercury is added to gold-bearing material, the two metals form an amalgam. Mercury is later separated from amalgam by retorting. Extraction of gold and other precious metals from their ores by treatment with mercury is called amalgamation. Gold dissolves in aqua regia, a mixture of hydrochloric and nitric acids, and in sodium or potassium cyanide. The latter solvent is the basis for the cyanide process that is used to recover gold from low-grade ore.

Hydraulic placer mining at Lost Chicken Hill Mine, near Chicken, Alaska. The firehose blasts the sediment outcrop, washing away sand, clay, gravel and gold particles. The material is then processed to remove the gold. USGS image.

Fineness, Karats and Troy Ounces

The degree of purity of native gold, bullion (bars or ingots of unrefined gold), and refined gold is stated in terms of gold content. "Fineness" defines gold content in parts per thousand. For example, a gold nugget containing 885 parts of pure gold and 115 parts of other metals , such as silver and copper , would be considered 885-fine. "Karat" indicates the proportion of solid gold in an alloy based on a total of 24 parts. Thus, 14-karat (14K) gold indicates a composition of 14 parts of gold and 10 parts of other metals. Incidentally, 14K gold is commonly used in jewelry manufacture. "Karat" should not be confused with "carat," a unit of weight used for precious stones.

The basic unit of weight used in dealing with gold is the troy ounce. One troy ounce is equivalent to 20 troy pennyweights. In the jewelry industry, the common unit of measure is the pennyweight (dwt.) which is equivalent to 1.555 grams.

The term "gold-filled" is used to describe articles of jewelry made of base metal which are covered on one or more surfaces with a layer of gold alloy. A quality mark may be used to show the quantity and fineness of the gold alloy. In the United States no article having a gold alloy coating of less than 10-karat fineness may have any quality mark affixed. Lower limits are permitted in some countries.

No article having a gold alloy portion of less than one-twentieth by weight may be marked "gold-filled," but articles may be marked "rolled gold plate" provided the proportional fraction and fineness designations are also shown. Electroplated jewelry items carrying at least 7 millionths of an inch (0.18 micrometers) of gold on significant surfaces may be labeled "electroplate." Plated thicknesses less than this may be marked "gold flashed" or "gold washed."

Gold sluice: Portable gold sluice. Miners place the sluice in the stream and dump sediments in the upstream side. The current transports the sediments through the sluice and the heavy gold particles become lodged in the sluice. One miner can process a lot more sediment through a sluice than through a gold pan. Image copyright iStockphoto / LeeAnn Townsend.

Formation of Primary Gold Deposits - Lode Gold

Gold is relatively scarce in the earth, but it occurs in many different kinds of rocks and in many different geological environments. Though scarce, gold is concentrated by geologic processes to form commercial deposits of two principal types: lode (primary) deposits and placer (secondary) deposits.

Lode deposits are the targets for the "hardrock" prospector seeking gold at the site of its deposition from mineralizing solutions. Geologists have proposed various hypotheses to explain the source of solutions from which mineral constituents are precipitated in lode deposits.

One widely accepted hypothesis proposes that many gold deposits, especially those found in igneous and sedimentary rocks , formed from circulating groundwaters driven by heat from bodies of magma (molten rock) intruded into the Earth's crust within about 2 to 5 miles of the surface. Active geothermal systems, which are exploited in parts of the United States for natural hot water and steam, provide a modern analog for these gold-depositing systems. Most of the water in geothermal systems originates as rainfall, which moves downward through fractures and permeable beds in cooler parts of the crust and is drawn laterally into areas heated by magma, where it is driven upward through fractures. As the water is heated, it dissolves metals from the surrounding rocks. When the heated waters reach cooler rocks at shallower depths, metallic minerals precipitate to form veins or blanket-like ore bodies.

Another hypothesis suggests that gold-bearing solutions may be expelled from magma as it cools, precipitating ore materials as they move into cooler surrounding rocks. This hypothesis is applied particularly to gold deposits located in or near masses of granitic rock, which represent solidified magma.

A third hypothesis is applied mainly to gold-bearing veins in metamorphic rocks that occur in mountain belts at continental margins. In the mountain-building process, sedimentary and volcanic rocks may be deeply buried or thrust under the edge of the continent, where they are subjected to high temperatures and pressures resulting in chemical reactions that change the rocks to new mineral assemblages (metamorphism). This hypothesis suggests that water is expelled from the rocks and migrates upwards, precipitating ore materials as pressures and temperatures decrease. The ore metals are thought to originate from the rocks undergoing active metamorphism.

The primary concerns of the prospector or miner interested in a lode deposit of gold are to determine the average gold content (tenor) per ton of mineralized rock and the size of the deposit. From these data, estimates can be made of the deposit's value. One of the most commonly used methods for determining the gold and silver content of mineralized rocks is the fire assay. The results are reported as troy ounces of gold or silver or both per short avoirdupois ton of ore or as grams per metric ton of ore.

Gold dredge: A scuba diver vacuums sediment to be processed by a portable gold dredge. Scuba gear allows the prospector to carefully get access to cracks and crevices on the stream bed where gold nuggets might be lodged. Image copyright iStockphoto / Gary Ferguson.

Concentration of Gold in Placer Deposits

Placer deposits represent concentrations of gold derived from lode deposits by erosion, disintegration or decomposition of the enclosing rock, and subsequent concentration by gravity.

Gold is extremely resistant to weathering and, when freed from enclosing rocks, is carried downstream as metallic particles consisting of "dust," flakes, grains, or nuggets. Gold particles in stream deposits are often concentrated on or near bedrock, because they move downward during high-water periods when the entire bed load of sand, gravel, and boulders is agitated and is moving downstream. Fine gold particles collect in depressions or in pockets in sand and gravel bars where the stream current slackens. Concentrations of gold in gravel are called "pay streaks."

Gold drywasher: A portable dry washer used to sift gold nuggets from soil where water is not available. Soil is dumped into the top pan and is shaken through the bottom pan. Heavy gold nuggets are mechanically separated from lighter materials. Image copyright iStockphoto / Arturo M. Enriquez.

Prospecting for Placer Deposits

In gold-bearing country, prospectors look for gold where coarse sands and gravel have accumulated and where "black sands" have concentrated and settled with the gold. Magnetite is the most common mineral in black sands, but other heavy minerals such as cassiterite , monazite , ilmenite , chromite , platinum-group metals, and some gemstones may be present.

Placer deposits have formed in the same manner throughout the Earth's history. The processes of weathering and erosion create surface placer deposits that may be buried under rock debris. Although these "fossil" placers are subsequently cemented into hard rocks, the shape and characteristics of old river channels are still recognizable.

Gold Books and Panning Supplies

Free Gold Assay

The content of recoverable free gold in placer deposits is determined by the free gold assay method, which involves amalgamation of gold-bearing concentrate collected by dredging, hydraulic mining, or other placer mining operations. In the period when the price of gold was fixed, the common practice was to report assay results as the value of gold (in cents or dollars) contained in a cubic yard of material. Now results are reported as grams per cubic yard or grams per cubic meter.

Through laboratory research, the U.S. Geological Survey has developed new methods for determining the gold content of rocks and soils of the Earth's crust. These methods, which detect and measure the amounts of other elements as well as gold, include atomic absorption spectrometry, neutron activation, and inductively coupled plasma-atomic emissionon spectrometry. These methods enable rapid and extremely sensitive analyses to be made of large numbers of samples.

Early Gold Finds and Production

Gold was produced in the southern Appalachian region as early as 1792 and perhaps as early as 1775 in southern California. The discovery of gold at Sutter's Mill in California sparked the gold rush of 1849-50, and hundreds of mining camps sprang to life as new deposits were discovered. Gold production increased rapidly. Deposits in the Mother Lode and Grass Valley districts in California and the Comstock Lode in Nevada were discovered during the 1860's, and the Cripple Creek deposits in Colorado began to produce gold in 1892. By 1905 the Tonopah and Goldfield deposits in Nevada and the Alaskan placer deposits had been discovered, and United States gold production for the first time exceeded 4 million troy ounces a year--a level maintained until 1917.

During World War I and for some years thereafter, the annual production declined to about 2 million ounces. When the price of gold was raised from $20.67 to $35 an ounce in 1934, production increased rapidly and again exceeded the 4-million-ounce level in 1937. Shortly after the start of World War II, gold mines were closed by the War Production Board and not permitted to reopen until 1945.

From the end of World War II through 1983, domestic mine production of gold did not exceed 2 million ounces annually. Since 1985, annual production has risen by 1 million to 1.5 million ounces every year. By the end of 1989, the cumulative output from deposits in the United States since 1792 reached 363 million ounces.

Consumption of Gold

Consumption of gold in the United States ranged from about 6 million to more than 7 million troy ounces per year from 1969 to 1973, and from about 4 million to 5 million troy ounces per year from 1974 to 1979, whereas during the 1970's annual gold production from domestic mines ranged from about 1 million to 1.75 million troy ounces. Since 1980 consumption of gold has been nearly constant at between 3 and 3.5 million troy ounces per year. Mine production has increased at a quickening pace since 1980, reaching about 9 million troy ounces per year in 1990, and exceeding consumption since 1986. Prior to 1986, the balance of supply was obtained from secondary (scrap) sources and imports. Total world production of gold is estimated to be about 3.4 billion troy ounces, of which more than two-thirds was mined in the past 50 years. About 45 percent of the world's total gold production has been from the Witwatersrand district in South Africa.

The largest gold mine in the United States is the Homestake mine at Lead, South Dakota. This mine, which is 8,000 feet deep, has accounted for almost 10 percent of total United States gold production since it opened in 1876. It has combined production and reserves of about 40 million troy ounces.

Disseminated Deposits and By-Product Gold

In the past two decades, low-grade disseminated gold deposits have become increasingly important. More than 75 such deposits have been found in the Western States, mostly in Nevada. The first major producer of this type was the Carlin deposit, which was discovered in 1962 and started production in 1965. Since then many more deposits have been discovered in the vicinity of Carlin, and the Carlin area now comprises a major mining district with seven operating open pits producing more than 1,500,000 troy ounces of gold per year.

About 15 percent of the gold produced in the United States has come from mining other metallic ores. Where base metals- -such as copper, lead, and zinc--are deposited, either in veins or as scattered mineral grains, minor amounts of gold are commonly deposited with them. Deposits of this type are mined for the predominant metals, but the gold is also recovered as a byproduct during processing of the ore. Most byproduct gold has come from porphyry deposits, which are so large that even though they contain only a small amount of gold per ton of ore, so much rock is mined that a substantial amount of gold is recovered. The largest single source of byproduct gold in the United States is the porphyry deposit at Bingham Canyon, Utah, which has produced about 18 million troy ounces of gold since 1906.

Role of a Geologist in Gold Prospecting

Geologists examine all factors controlling the origin and emplacement of mineral deposits, including those containing gold. Igneous and metamorphic rocks are studied in the field and in the laboratory to gain an understanding of how they came to their present location, how they crystallized to solid rock, and how mineral-bearing solutions formed within them. Studies of rock structures, such as folds, faults, fractures, and joints, and of the effects of heat and pressure on rocks suggest why and where fractures occurred and where veins might be found. Studies of weathering processes and transportation of rock debris by water enable geologists to predict the most likely places for placer deposits to form. The occurrence of gold is not capricious; its presence in various rocks and its occurrence under differing environmental conditions follow natural laws. As geologists increase their knowledge of the mineralizing processes, they improve their ability to find gold.

| More Gold |

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Gold mining is the extraction of gold by mining. Historically, mining gold from alluvial deposits used manual separation processes, such as gold panning. The expansion of gold mining to ores that are not on the surface has led to more complex extraction processes such as pit mining and gold cyanidation. In the 20th and 21st centuries, most ...

Gold mining companies should demonstrate their awareness of their impacts on society and local economies; Responsible gold mining means working with civil society and consulting with...

Gold mining can contaminate drinking water and destroy pristine environments, endangering the health of people and ecosystems. Families on the front lines of mining, drilling, and fracking need your help.

A USGS publication on the history of gold uses, gold mining, gold prospecting, assays and gold production.

The actual mining of gold is just one step of the gold mining process. Learn how gold is mined and the five stages of a large scale gold mining project.

Executive summary. Despite the industry’s scale, the socio-economic impacts of the gold mining industry are not well understood. Gold mining companies are a major source of income and...

Key facts on the social and economic contribution of gold mining. When undertaken responsibly, gold mining makes a very significant contribution to social and economic development of host countries and communities. In this section, we set out a number of key facts and perspectives on how this is achieved. Fact #1.

The report looks at the social and economic impacts of gold mining, analysing both direct and indirect impacts and covering a substantial portion of corporate, costed gold production (and broadening the scope to non-Member production).

The main contribution of this paper is to shed light on the welfare effects of gold mining in a detailed, in-depth country study of Ghana, a country with a long tradition of gold mining and a recent, large expansion in capital-intensive and industrial-scale production.

Gold mining and other mining activities globally, especially in developing nations, remain controversial due to evidence of a noticeable impact on the local climate, natural environment and socio-economic status of the local population.