An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Levels, antecedents, and consequences of critical thinking among clinical nurses: a quantitative literature review

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding email: [email protected]

Received 2020 Aug 12; Accepted 2020 Sep 7; Collection date 2020.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The purpose of this study was to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of critical thinking within the clinical nursing context. In this review, we addressed the following specific research questions: what are the levels of critical thinking among clinical nurses?; what are the antecedents of critical thinking?; and what are the consequences of critical thinking? A narrative literature review was applied in this study. Thirteen articles published from July 2013 to December 2019 were appraised since the most recent scoping review on critical thinking among nurses was conducted from January 1999 to June 2013. The levels of critical thinking among clinical nurses were moderate or high. Regarding the antecedents of critical thinking, the influence of sociodemographic variables on critical thinking was inconsistent, with the exception that levels of critical thinking differed according to years of work experience. Finally, little research has been conducted on the consequences of critical thinking and related factors. The above findings highlight the levels, antecedents, and consequences of critical thinking among clinical nurses in various settings. Considering the significant association between years of work experience and critical thinking capability, it may be effective for organizations to deliver tailored education programs on critical thinking for nurses according to their years of work experience.

Keywords: Nurses, Critical thinking, Literature review

Introduction

As the healthcare environment has become more complicated and detail-oriented and health professions have become more advanced, more nursing professionalism has been expected in recent years. To be more competent, nurses should be critical thinkers who can effectively cope with advancing technologies, human resource limitations, and the high level of acuity required in diverse healthcare settings. Critical thinking (CT) is considered to be a crucial element for clinical decision-making by nurses, and improved empowerment to engage in CT is considered to be a core program outcome in nursing education. However, recent studies have reported difficulties in applying CT to nursing practice [ 1 , 2 ], moderately low levels of CT among nurses [ 3 ], and differences in the understanding of the meaning of CT among nursing educators and scholars [ 4 ].

Since CT was emphasized as an essential component of the nursing process in the 1970s, numerous nursing scholars have attempted to define the concept of CT for nursing [ 5 ]. During the introductory period of CT, intellectual or cognitive skills were mostly emphasized. A decade later, affective disposition was also noted as an important component of CT in the context of a caring relationship [ 6 ]. Emotional involvement enables nurses to genuinely feel the suffering and pain that patients experience [ 7 ]. In 2000, Scheffer and Rubenfeld [ 8 ] identified essential components of CT, including 10 affective habits of the mind and 7 cognitive skills, by using the Delphi method to arrive at a consensus on an acceptable definition of CT. In recent years, nurses have been increasingly expected to develop both CT affective dispositions and CT cognitive skills [ 9 ]. Affective dispositions such as being open-minded, inquisitive, and seeking truth can stimulate an individual towards using CT through a reasoning process [ 10 ]. Meanwhile, cognitive skills may help nurses analyze their inferences, explain their interpretations, and evaluate their analyses [ 11 ]. Knowledge is also necessary to strengthen and support the cognitive process of CT [ 3 , 10 ].

To our knowledge, the most recent scoping review on the concept of CT in the nursing field was reported in 2015 [ 5 ]; according to this comprehensive review [ 5 ], there was growing interest in the study of the concepts and dimensions of CT experienced by nurses and nursing students, as well as in the development of training strategies for both students and professionals. However, a direction for further research into CT among clinical nurses was to specifically focus on its features or tendencies and changes in the CT phenomenon as time goes by, because confusing perspectives and poor knowledge of CT among nurse-educators can threaten the nursing profession [ 12 ]. Furthermore, an extensive review of quantitative research findings on CT among nurses is lacking, since only a scoping review was published in 2015 [ 5 ]. Thus, it is necessary to better understand how clinical nurses exercise CT to cultivate their clinical decision-making skills by reflecting on the contemporary nursing context.

The purpose of this study was to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of CT in the clinical nursing context. In this review, we specifically addressed the following research questions: what are the levels of CT among clinical nurses?; what are the antecedents of CT?; and, what are the consequences of CT?

Ethics statement

This study did not have human subjects; therefore, neither institutional review board approval nor informed consent was required.

Study design

A narrative literature review was used. We followed the methodologies described by the Center for Reviews and Dissemination for undertaking reviews [ 13 ] and by Petticrew and Roberts [ 14 ], who addressed the practical guide as an alternative to systematic reviews in the social sciences, since our major goal was to synthesize the individual studies narratively and not to evaluate the efficacy and safety of interventions or programs.

Materials and/or subjects

Information sources.

In this study, CT in clinical nursing was analyzed using a narrative review design to provide an overview of CT among nurses. We conducted an extensive search in the MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Ovid databases for articles published from July 2013 to December 2019 on CT among nurses, since Zuriguel Pérez et al. [ 5 ] comprehensively conducted a scoping review of articles on this topic that included research published from January 1999 to June 2013.

The following keywords were used: “critical thinking,” “professional judgment,” “clinical judgment,” and “clinical competence.” We also used the snowball method to identify additional studies. Titles and abstracts were screened, and studies were included if they presented empirical research on CT among clinical nurses, published in English from July 2013 to December 2019. Publications were excluded if they were reviews, case studies, or unpublished dissertations, or if CT was only studied among nursing students.

Search outcomes

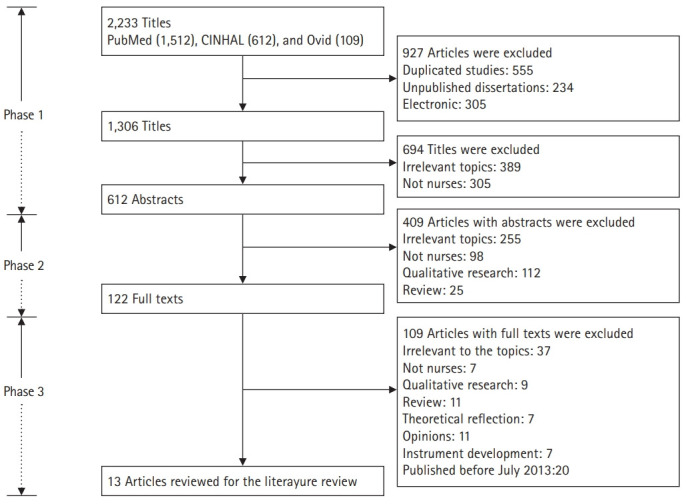

Both researchers (Y.L. and Y.O.) carried out the literature search to ensure that all relevant articles would be identified. The search produced a total of 2,233 articles. Candidate articles were screened by title. Titles that both researchers agreed were irrelevant to the aim of this review, as well as duplicates, were excluded. All other articles (612) were assessed as potentially relevant to the topic, and those for which consensus was reached between the authors were forwarded to the next phase ( Fig. 1 ).

Flow diagram of the process of identifying and including articles for this review.

All abstracts from the articles selected during phase 1 were evaluated by reading them and checking whether they met the inclusion criteria. All studies that met the criteria proceeded to the next phase of the search process. If no consensus was reached for a particular article, the article was also forwarded to the next phase. All other studies (490) were excluded ( Fig. 1 ).

In the final phase of the search process, a total of 122 articles from phase 2 were read and evaluated in light of the inclusion criteria. Of these, articles with text irrelevant to the study (109) were excluded, as the papers did not focus on CT or nurses, did not employ quantitative research design, or were published before July 2013. A final number of 13 articles were included ( Fig. 1 ).

Quality appraisal

We evaluated the included studies using assessment sheets prepared and tested by Hawker et al. [ 15 ], who developed an instrument that is capable of appraising methodologically heterogeneous studies. The data extraction sheet explores 9 components in detail: title and abstract, introduction and aims, method and data, sampling, data analysis, ethics and bias, results, transferability or generalizability, and implications and usefulness. In our review, each of these areas was assessed using the criteria developed by Hawker et al. [ 15 ] and rated on a scale of 1 (very poor) to 4 (very good). The scores for each assessment were then summed to obtain an overall score and rating, which ranged from very poor (9) to very good (36). Any article scoring less than 18 was considered to be of poor to very poor quality.

Using the assessment described above, the selected studies had scores ranging from 23 to 33 out of 36. Hence, all studies were included in the review ( Table 1 ). All studies mentioned either a research question or an objective. In each article, the study design was described. Procedures or interventions were described in all studies, including three quasi-experimental studies [ 16 - 18 ]. Random sampling and purposive sampling were most commonly employed. Some studies, however, failed to state their sampling methods. Five studies determined the sample size by using power analysis [ 16 , 19 , 20 ], the Raosoft sample size calculator [ 21 ], or Solvin’s formula [ 22 ]. All studies addressed ethical considerations except for 1 study [ 23 ]; however, no studies described or elaborated on whether the researchers had received permission to use an original or translated version of the research instruments.

Studies included in the literature review

RR, response rate; CT, critical thinking; RN, registered nurse; IRB, institutional review board.

Data abstraction and synthesis

The data abstraction and synthesis process consisted of re-reading, isolating, comparing, categorizing, and relating relevant data. Included articles were read repeatedly to obtain an overall understanding of the material. Relevant data were gathered and classified into 3 categories: levels of CT, antecedents of CT, and consequences of CT.

Study selection

Our review included 13 publications ( Table 1 ). The studies were conducted in 7 different countries: Korea and the United States (n=3, for each country), Spain and Taiwan (n=2, for each country); and Malaysia, Turkey, and Egypt (n=1, for each country). The research settings were hospitals (n=6), intensive or critical care units (n=3), acute care units (n=2), and psychiatric care units (n=1). One study included nurses working in critical care and emergency units [ 24 ]. In all studies, the sample consisted of only nurses.

Study characteristics

The methodological features of the included studies are summarized in Table 1 . Twelve studies implemented quantitative research to examine the phenomenon of CT, while 1 study used a mixed-methods research approach [ 18 ]. Six of the included studies implemented a quasi-experimental design to evaluate the effect of their programs on CT among clinical nurses [ 16 - 18 , 23 - 25 ]. All included studies described institutional review board approval, except for 3 studies, which either stated that researchers verbally obtained the consent of the participants to be included in the research [ 22 , 26 ] or did not mention this issue [ 23 ].

CT was evaluated employing the California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory [ 21 , 22 , 24 , 26 ], Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory [ 18 , 19 ], Critical Thinking Disposition [ 17 , 20 ], Nursing Critical Thinking in Clinical Practice Questionnaire [ 27 , 28 ], Clinical Critical Thinking Skill Test [ 16 ], Health Sciences Reasoning Test (HSRT) [ 25 ], or a self-evaluation tool to measure 5 key indicators of the development of CT [ 23 ]. All studies, except for 1, utilized a validated version of the original instruments in the appropriate language or validated the instruments in their research [ 22 ]. All studies except for 3 reported internal consistency reliability [ 22 , 23 , 25 ].

Levels of critical thinking

All studies measured the levels of CT among nurses, except for 1 study [ 20 ] ( Table 1 ). Clinical nurses in 4 studies reported low [ 26 ], moderate [ 22 , 27 ], and high [ 21 ] levels of CT. Chen et al. [ 19 ] reported that experienced nurses, with an average of 18.38 years of work experience, had higher CT scores than novice registered nurses did. Similarly, Zuriguel-Perez et al. [ 28 ] reported that the level of CT among more experienced nurse managers was higher than among other nurses.

Five studies showed that their developed programs significantly improved the levels of CT among nurses in the experimental group compared to nurses in the control group [ 16 - 18 , 23 , 24 ]. One study presented a significant increase in the mean overall CT score for the HSRT on the posttest using a 1-group pretest-posttest design [ 25 ]. In particular, 5 programs—a work-based critical reflection program [ 16 ], a scenario-based simulation training program [ 17 ], case studies with videotaped vignettes [ 25 ], and concept mapping [ 23 ]—had positive effects on CT levels among novice nurses. Zori et al. [ 24 ] reported significant effects of a reflective journaling exercise to strengthen CT dispositions among nurses with diverse work experience. Hung et al. [ 18 ] developed a problem-based learning program for mental health care nurses for 3 hours every week, for a total of 5 weeks (15 hours total).

Antecedents of critical thinking

Seven studies reported inconsistent findings regarding the influence of 1 or more sociodemographic variables on CT ( Table 1 ). According to these studies, there were significant differences in CT across sociodemographic variables, including age [ 19 , 21 , 27 , 28 ], gender [ 21 ], ethnicity [ 21 ], years of experience [ 19 , 21 , 27 , 28 ], and educational level [ 21 , 28 ]. In 3 studies, older nurses, those with more clinical experience, or those with higher levels of education had higher levels of CT [ 19 , 21 , 28 ]. Although Ludin [ 21 ] reported significant differences in the levels of CT according to gender, ethnicity, and educational level, detailed information was not provided. In contrast, Mahmoud and Mohamed [ 22 ] reported that none of the sociodemographic variables or job characteristics had statistically significant relationships with the total CT disposition and, in 2 studies, there were no significant relationships between CT levels and educational level [ 26 , 27 ], years of experience [ 26 ], gender [ 27 ], or work units [ 27 ]. Nurses had higher levels of CT when they had higher levels of self-reflection [ 19 ] and lower levels of perception of barriers to research use [ 20 ].

Consequences of critical thinking

Only 1 study investigated the consequences of CT [ 20 ], and found that CT disposition of nurses positively influenced evidence-based practice ( Table 1 ). In this study, Kim et al. [ 20 ] found that the relationship between barriers to research use and evidence-based practice was mediated by CT disposition.

Methodological issues

Studies from 6 different countries were included. Most of the studies were done in Asian countries; only 2 of the studies were conducted in Europe. Synthesizing and integrating data from different countries and cultures is a complex and challenging task [ 29 ], especially since differences in cultural attitudes on CT extend beyond our expertise. The restricted professional autonomy perceived by nurses, which impeded CT, may be different for each culture or country. For instance, several studies in Asia have reported that nurses lack or have limited authority in providing care for their patients [ 30 , 31 ]; furthermore, while CT allows nurses to generate new ideas quickly, become more flexible, and act independently and confidently, the scope of their action is still ultimately limited by the physician’s clinical decisions [ 10 ]. Thus, several Asian nursing scholars have stressed the growth of professional autonomy among nurses through exercising higher levels of CT as an area that needs support to improve nurses’ clinical competence.

In the studies we reviewed, 7 different instruments were used. Due to this diversity of instruments, it was difficult to compare and integrate quantitative data. In addition, some studies utilized instruments without testing reliability and validity; thus, it is recommended to validate CT assessment instruments used in future research to ensure their reliability. A large range in sample sizes and response rates, possible non-responder bias, and validation of the instruments restricted to small populations limited the representativeness of our study results.

Substantive findings

Although the assessment tools used to measure the level of CT varied across the studies reviewed, the level of CT was mostly moderate or high among the nurses evaluated. This may be partly due to the emphasis of CT in nursing education in recent years; furthermore, CT is now recognized as an essential competency among nurses and is required for the accreditation of nursing education [ 9 , 32 ]. However, this result contrasts with other research that reported a low level of CT among nursing students [ 33 ]. Further research is needed to verify the differences between nurses and nursing students according to factors influencing CT disposition and skills.

Our review complements the results of a previous review that scoped the concept of CT in the nursing field [ 5 ]. For instance, as antecedents of CT, the association between sociodemographic variables and CT can only be revealed by quantitative studies. It is necessary to examine the relationships between them in the future since the influence of sociodemographic variables on CT was found to be inconsistent in our study, except for years of work experience, which showed a consistent association with CT capacity. This finding may be associated with the significant experience gained by more senior nurses, which complements their theoretical knowledge and clinical decision-making [ 34 ] and enables them to be capable of better reflecting on past experiences, which may foster a deeper understanding of the situation [ 19 ]. On the contrary, less-experienced nurses had difficulties in exercising CT because of their perceptions of a gap between theory and practice with reference to their education and the real workplace setting [ 16 ]. Thus, it can be useful for senior nurses to share and reflect on their successful experiences of applying CT for patient care through group discussions; meanwhile, for novice nurses, a clear and detailed approach on exercising CT to reduce the gap between theories and the clinical setting may be beneficial. For this reason, a tailored education program on CT should be developed according to nurses’ years of work experience.

Self-reflection was also significantly related to CT among nurses in our review. This finding can be explained in terms of genuine self-reflection which can help them develop their CT dispositions and skills by balancing a lack of confidence and professional autonomy [ 34 ]. CT encourages nurses to generate new ideas quickly, be flexible, and act independently and confidently [ 29 ]. In contrast, nurses’ CT becomes more limited when they are more dependent on physicians’ clinical decisions. Meanwhile, expert nurses are not confined to or constrained by theoretical knowledge and are able to interpret situations by actively utilizing their nursing care experiences with past patients through exercising CT in their decision-making process [ 9 , 40 ]. To promote and encourage CT, nurses need to be more independent, confident, and responsible. As nurses’ autonomy develops, the need to think critically is further promoted [ 29 , 33 ]. However, nurses in some nursing environments have reported limited or restricted professional autonomy due to existing rigid and hierarchical cultures, as well as physician-centered paradigms in hospitals, which can hinder nurses from exercising CT [ 35 - 38 ]. More research is required regarding autonomy and CT among nurses in relation to their perceptions of the organizational atmosphere.

Our review revealed that there is limited empirical research on the consequences of CT, since only 1 of the included studies investigated the consequences of CT. CT stimulates nurses to explore related knowledge and establish priorities for solving patients` clinical problems [ 39 ]. As a method of assessing, planning, implementing, reevaluating, and reconstructing nursing care, a CT approach encourages nurses to challenge established theory and practice [ 5 , 9 ]. In addition, good clinical judgement results from exercising CT by advancing nursing competence in contemporary healthcare environments, where the complexity of data and amount of newly developed knowledge increases daily [ 10 ]. Papathanasiou et al. [ 9 ] emphasized that nurses’ ability to find specific solutions to certain problems is easily achieved when creativity and CT work together. Nevertheless, an integrated review found no relationship between CT and clinical decision-making in nursing [ 40 ]. Further research is recommended to explore the consequences of CT in nursing.

Limitations

Despite complementing the findings of a previous scoping review [ 5 ], our review has 2 major limitations. First, a more synthesized approach should be attempted, including both quantitative and qualitative studies, in order to facilitate a more in-depth examination of our research topic. Second, access to all resources via electronic databases was not possible and only studies written in English were included in our review.

Our review highlighted the levels, antecedents, and consequences of CT among clinical nurses in various settings. Further quantitative studies are recommended using representative sample sizes and validated instruments with high and stable reliability to enhance our knowledge of this issue through optimal methodologies. Considering the significant association between years of work experience and CT capability, it would be helpful and effective for organizations to deliver a tailored education program on CT developed according to years of work experience to enhance CT among nurses when providing care for their patients. To make progress towards this goal, however, further research is needed to clarify the antecedents of CT and to explore its consequences.

Acknowledgments

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: YL, YO. Data curation: YL, YO. Formal analysis: YL, YO. Funding acquisition: YO. Methodology: YL, YO. Project administration: YO. Visualization: YO. Writing–original draft: YL, YO. Writing–review & editing: YL, YO.

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

This work was supported by the Hallym University Research Fund, 2020 (HRF-202007-014).

Data availability

Supplementary materials

Supplement 1. Audio recording of the abstract.

- 1. Missen K, McKenna L, Beauchamp A, Larkins JA. Qualified nurses’ rate new nursing graduates as lacking skills in key clinical areas. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25:2134–2143. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13316. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Lang GM, Beach NL, Patrician PA, Martin C. A cross-sectional study examining factors related to critical thinking in nursing. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2013;29:8–15. doi: 10.1097/NND.0b013e31827d08c8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Gezer N, Yildirim B, Ozaydin E. Factors in the critical thinking disposition and skills of intensive care nurses. J Nurs Care. 2017;6:1000390. doi: 10.4172/2167-1168.1000390. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Price B. Applying critical thinking to nursing. Nurs Stand. 2015;29:49–58. doi: 10.7748/ns.29.51.49.e10005. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Zuriguel Perez E, Lluch Canut MT, Falco Pegueroles A, Puig Llobet M, Moreno Arroyo C, Roldan Merino J. Critical thinking in nursing: scoping review of the literature. Int J Nurs Pract. 2015;21:820–830. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12347. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Tanner CA. Spock would have been a terrible nurse (and other issues related to critical thinking in nursing) J Nurs Educ. 1997;36:3–4. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19970101-03. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Gastmans C. Dignity-enhancing nursing care: a foundational ethical framework. Nurs Ethics. 2013;20:142–149. doi: 10.1177/0969733012473772. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Scheffer BK, Rubenfeld MG. A consensus statement on critical thinking in nursing. J Nurs Educ. 2000;39:352–359. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20001101-06. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Papathanasiou IV, Kleisiaris CF, Fradelos EC, Kakou K, Kourkouta L. Critical thinking: the development of an essential skill for nursing students. Acta Inform Med. 2014;22:283–286. doi: 10.5455/aim.2014.22.283-286. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Von Colln-Appling C, Giuliano D. A concept analysis of critical thinking: a guide for nurse educators. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;49:106–109. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.11.007. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Chan ZC. A systematic review of critical thinking in nursing education. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33:236–240. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.01.007. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Yue M, Zhang M, Zhang C, Jin C. The effectiveness of concept mapping on development of critical thinking in nursing education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;52:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.02.018. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination . York (PA): University of York NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; 2009. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 5]. Available from: https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf . [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide. New York (NY): John Wiley & Sons; 2008. p. 336. [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:1284–1299. doi: 10.1177/1049732302238251. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Kim YH, Min J, Kim SH, Shin S. Effects of a work-based critical reflection program for novice nurses. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:30. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1135-0. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Jung D, Lee SH, Kang SJ, Kim JH. Development and evaluation of a clinical simulation for new graduate nurses: a multi-site pilot study. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;49:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.11.010. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Hung TM, Tang LC, Ko CJ. How mental health nurses improve their critical thinking through problem-based learning. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2015;31:170–175. doi: 10.1097/NND.0000000000000167. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Chen FF, Chen SY, Pai HC. Self-reflection and critical thinking: the influence of professional qualifications on registered nurses. Contemp Nurse. 2019;55:59–70. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2019.1590154. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Kim SA, Song Y, Sim HS, Ahn EK, Kim JH. Mediating role of critical thinking disposition in the relationship between perceived barriers to research use and evidence-based practice. Contemp Nurse. 2015;51:16–26. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2015.1095053. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Ludin SM. Does good critical thinking equal effective decision-making among critical care nurses?: a cross-sectional survey. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2018;44:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2017.06.002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Mahmoud AS, Mohamed HA. Critical thinking disposition among nurses working in puplic hospitals at port-said governorate. Int J Nurs Sci. 2017;4:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2017.02.006. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Wahl SE, Thompson AM. Concept mapping in a critical care orientation program: a pilot study to develop critical thinking and decision-making skills in novice nurses. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2013;44:455–460. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20130916-79. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Zori S, Kohn N, Gallo K, Friedman MI. Critical thinking of registered nurses in a fellowship program. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2013;44:374–380. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20130603-03. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Hooper BL. Using case studies and videotaped vignettes to facilitate the development of critical thinking skills in new graduate nurses. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2014;30:87–91. doi: 10.1097/NND.0000000000000009. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Yurdanur D. Critical thinking competence and dispositions among critical care nurses: a descriptive study. Int J Caring Sci. 2016;9:489–495. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Zuriguel-Perez E, Falco-Pegueroles A, Agustino-Rodriguez S, Gomez-Martin MD, Roldan-Merino J, Lluch-Canut MT. Clinical nurses’s critical thinking level according to sociodemographic and professional variables (phase II): a correlational study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2019;41:102649. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2019.102649. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Zuriguel-Perez E, Lluch-Canut MT, Agustino-Rodriguez S, Gomez-Martin MD, Roldan-Merino J, Falco-Pegueroles A. Critical thinking: a comparative analysis between nurse managers and registered nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2018;26:1083–1090. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12640. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Kim M, Oh Y, Kong B. Ethical conflicts experienced by nurses in geriatric hospitals in South Korea: “if you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen”. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4442. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124442. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Mousavi SR, Amini K, Ramezani-badr F, Roohani M. Correlation of happiness and professional autonomy in Iranian nurses. J Res Nurs. 2019;24:622–632. doi: 10.1177/1744987119877421. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Park IS, Suh YO, Park HS, Kang SY, Kim KS, Kim GH, Choi YH, Kim HJ. Item development process and analysis of 50 case-based items for implementation on the Korean Nursing Licensing Examination. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2017;14:20. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2017.14.20. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Kaya H, Şenyuva E, Bodur G. Developing critical thinking disposition and emotional intelligence of nursing students: a longitudinal research. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;48:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.09.011. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Jacob E, Duffield C, Jacob D. Development of an Australian nursing critical thinking tool using a Delphi process. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:2241–2247. doi: 10.1111/jan.13732. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Aeschbacher R, Addor V. Institutional effects on nurses’ working conditions: a multi-group comparison of public and private non-profit and for-profit healthcare employers in Switzerland. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16:58. doi: 10.1186/s12960-018-0324-6. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Gallego G, Dew A, Lincoln M, Bundy A, Chedid RJ, Bulkeley K, Brentnall J, Veitch C. Should I stay or should I go?: exploring the job preferences of allied health professionals working with people with disability in rural Australia. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13:53. doi: 10.1186/s12960-015-0047-x. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Asif M, Jameel A, Hussain A, Hwang J, Sahito N. Linking transformational leadership with nurse-assessed adverse patient outcomes and the quality of care: assessing the role of job satisfaction and structural empowerment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2381. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16132381. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Bvumbwe T. Perceptions of nursing students trained in a new model teaching ward in Malawi. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2015;12:53. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2015.12.53. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Chang SO, Kong ES, Kim CG, Kim HK, Song MS, Ahn SY, Lee YW, Cho MO, Choi KS, Kim NC. Exploring nursing education modality for facilitating undergraduate students’ critical thinking: focus group interview analysis. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2013;25:125–135. doi: 10.7475/kjan.2013.25.1.125. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Lee DS, Abdullah KL, Subramanian P, Bachmann RT, Ong SL. An integrated review of the correlation between critical thinking ability and clinical decision-making in nursing. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:4065–4079. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13901. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- View on publisher site

- PDF (785.7 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Advanced practice: critical thinking and clinical reasoning

Affiliations.

- 1 Advanced Critical Care Practitioner, Newcastle upon Tyne NHS Foundation Trust / Senior Lecturer in Advanced Critical Care Practice, Department of Nursing, Midwifery and Health, Northumbria University.

- 2 Advanced Critical Care Practitioner, South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

- PMID: 33983801

- DOI: 10.12968/bjon.2021.30.9.526

Clinical reasoning is a multi-faceted and complex construct, the understanding of which has emerged from multiple fields outside of healthcare literature, primarily the psychological and behavioural sciences. The application of clinical reasoning is central to the advanced non-medical practitioner (ANMP) role, as complex patient caseloads with undifferentiated and undiagnosed diseases are now a regular feature in healthcare practice. This article explores some of the key concepts and terminology that have evolved over the last four decades and have led to our modern day understanding of this topic. It also considers how clinical reasoning is vital for improving evidence-based diagnosis and subsequent effective care planning. A comprehensive guide to applying diagnostic reasoning on a body systems basis will be explored later in this series.

Keywords: Advanced practice; Clinical reasoning; Consultation; Critical thinking; Diagnostic accuracy.

- Advanced Practice Nursing*

- Clinical Reasoning*

- Nurse Practitioners* / psychology

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Effective decision-making: applying the theories to nursing practice.

Samantha Watkins

Emergency Department Staff Nurse, Frimley Health NHS Foundation Trust, Frimley

View articles · Email Samantha

Many theories have been proposed for the decision-making conducted by nurses across all practices and disciplines. These theories are fundamental to consider when reflecting on our decision-making processes to inform future practice. In this article three of these theories are juxtaposed with a case study of a patient presenting with an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). These theories are descriptive, normative and prescriptive, and will be used to analyse and interpret the process of decision-making within the context of patient assessment.

Decision-making is a fundamental concept of nursing practice that conforms to a systematic trajectory involving the assessment, interpretation, evaluation and management of patient-specific situations ( Dougherty et al, 2015 ). Shared decision-making is vital to consider in terms of patient autonomy and professional duty of care as set out in the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) (2018) Code, which underpins nursing practice. Consequently, the following assessment and decision-making processes were conducted within the remits of practice as a student nurse. Decision-making is a dynamic process in nursing practice, and the theories emphasise the importance of adaptability and reflective practice to identify factors that impact on patient care ( Pearson, 2013 ). Three decision-making theories will be explored within the context of a decision made in practice. To abide by confidentiality requirements, the pseudonym ‘Linda’ will be used throughout. Patient consent was obtained prior to writing.

Linda was a 71-year-old who had been admitted to the cardiac ward following an episode of unstable angina. She was on continuous cardiac monitoring as recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2016) guideline for chest pain of recent onset. During her stay on the ward, the tracing on the cardiac monitor indicated possible ST-segment elevation ( Thygesen et al, 2018 ). It was initially hypothesised that she might be experiencing an ACS ( Box 1 ) and could be haemodynamically unstable.

Box 1. Acute coronary syndrome

- Acute coronary syndrome is an umbrella term that includes three cardiac conditions that result from a reduction of oxygenated blood through the coronary arteries, causing myocardial ischaemia. An ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) connotes the complete occlusion of one or more of the coronary arteries, which is demonstrated by patient symptoms and ST-segment elevation seen on an electrocardiogram (ECG)

- A non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) results from a partial occlusion of a coronary artery. Patient symptoms often present alongside dynamic ST-segment depression, T-wave inversion or a normal ECG

- Unstable angina is a result of a transient occlusion of the coronary arteries causing symptoms at rest or on minimal exertion, which may be eased/resolved with rest with or without glyceryl trinitrate (GTN)

- Signs and symptoms of ischaemia experienced by patient include: chest pain with or without radiation to jaw, neck, back, shoulders or arms, which is described as squeezing or crushing. Associated symptoms of lethargy, syncope, pre-syncopal episodes, diaphoresis, dyspnoea, nausea or vomiting, anxiety or a feeling of impending doom often also prevail

Source: Deen, 2018

The possibility that Linda was experiencing ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) meant that she needed rapid assessment of her condition. Stephens (2019) recommended the use of the ABCDE assessment as a timely and effective tool to identify physiological deterioration in patients with chest pain. The student nurse's ABCDE assessment of Linda is shown in Box 2 .

Box 2. ABCDE assessment * of ‘Linda’

- Airway: patent, no audible sounds of obstruction; however, unable to speak in full sentences due to dyspnoea

- Breathing: dyspnoeic, respiratory rate of 27, saturations of 85% on room air—with guidance from the senior charge nurse, 80% oxygen via non-rebreathe mask was administered ( O'Driscoll et al, 2017 )

- Circulation: tachycardia of 112 beats per minute, hypotensive at 92/50 mmHg, oliguric, diaphoretic, and with cool peripherals and a thready radial pulse

- Disability: She was alert on the AVPU scale, but anxious and feeling lethargic. Blood glucose was 5.7 mmol/litre

- Exposure: no erythema or wounds noted. She stated she had central chest pain, which was radiating to her jaw and back, described as ‘pressure’, and rated as a seven out of ten

* in line with Resuscitation Council (2015)

NICE (2016) recommends that the first investigation for patients with chest pain is to conduct an ECG as a rapid and non-invasive assessment for a cardiac cause of the pain. This was carried out and 2 mm ST-segment elevation in the precordial leads V1-V3 was noted, indicating a possible anterior STEMI ( Amsterdam et al, 2014 ). The student nurse had had basic ECG interpretation training as part of the nursing degree undertaken, but had also received informal teaching from registered nursing staff in cardiology. The ECG findings were confirmed by the senior charge nurse after they were alerted to Linda's condition, symptoms, and National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS 2) ( Royal College of Physicians, 2017 ). The senior charge nurse escalated her care to the cardiology team. A diagnosis of STEMI was made by the cardiology team using the ECG findings and her physiological signs of deterioration from their assessment, within the context of her initial presentation to hospital for unstable angina. This diagnosis, coupled with the deterioration in her condition, meant that she required primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The NICE (2014) quality standard for acute coronary syndromes and the clinical guideline on STEMI ( NICE, 2013a ) recommend that primary PCI is initiated within 120 minutes to reperfuse the myocardium and prevent further myocardial cellular necrosis. This improves long-term patient outcomes ( Thygesen et al, 2018 ).

Decision-making theories

The recognition of an evolving STEMI on the cardiac monitor corresponds with the model of hypothetico-deductive reasoning ( Pearson, 2013 ) within the descriptive and normative theories ( Box 3 ). Thompson and Dowding (2009) highlighted that this model recognises that decision-making comprises four stages, beginning with cue acquisition. The specific pre-counter cues can be identified as the recognition of the abnormal tracing on the cardiac monitor ( Pearson, 2013 ), suggestive of ST-segment elevation, that indicated Linda might be experiencing haemodynamic deterioration with a cardiac cause. Subsequently, the decision to assess Linda formed the hypothesis generation phase of the decision and the recognition of the clinical signs as indicating STEMI ( Nickerson, 1998 ; Johansen and O'Brien, 2016 ). This hypothesis focused the assessment to identify and examine pertinent factors that supported this conjecture ( Pearson, 2013 ). However, the student nurse required more data to formulate a robust hypothesis thereby initiating the cue interpretation phase by conducting an ABCDE systematic assessment, including ECG. Lindsey (2013) argued that during cue interpretation, the health professional uses prescriptive guidelines to direct the assessment process and provide a rationale.

Box 3. Decision-making theories considered

- Descriptive theory: is concerned with each individuals’ moral beliefs regarding a particular decision

- Normative theory: connotes what decisions individuals should make logically

- Prescriptive theory: encompasses the policies that govern the remits of a decision within the evidence base that informs practice

Source: Pearson, 2013

Arguably, however, clinical knowledge of the pathophysiology of ACS is fundamental to effective cue interpretation, not simply the individual's knowledge of the NICE guidance ( NICE, 2013a ; 2013b ; 2014 ; 2016 ). The student nurse's existing knowledge of the symptoms of ACS supported the cue interpretation with assessing Linda's condition and possible diagnosis of ACS. This knowledge enriched the student nurse's understanding of the guidance, which could then effectively be applied as the central aspect of cue interpretation ( Deen, 2018 ).

Elstein and Schwartz (2002) conceded that the prescriptive theory knowledge synthesised for the decision must be accurate and evidence-based for hypothetico-deductive reasoning to be effective. Courtney and McCutcheon (2009) argued that reliance solely on clinical guidelines can limit decision-making and result in erroneous outcomes and should consequently be used in collaboration with the evidence base. By combining normative theory with prescriptive guidance, clinical decisions can be enriched and validated. Stevens (2013) highlighted that it is vital that the guidance used in corroboration with decision-making models is valid and reliable and therefore prescriptive theory must be critically evaluated against the evidence-base. The guidance published by NICE (2013a) is supported by the American College of Cardiology ( O'Gara et al, 2013 ), European Resuscitation Council ( Nikolaou et al, 2015 ), European Society of Cardiology ( Steg et al, 2012 ) and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand ( Chew et al, 2016 ). Accordingly, these guidelines highlight the clinical signs of STEMI and the diagnostic investigations pertinent to this condition. Within the remits of practice as a student nurse, this evidence supported the decision to escalate Linda's condition.

Antithetically, during cue interpretation and the hypothesis generation phases, Pearson (2013) emphasised the importance of considering multiple hypotheses extrapolated from the clinical data, resulting in the selection of the most appropriate hypothesis when more data are obtained. Despite this, during the interpretation of the cues for the hypothesis, the student nurse failed to consider differential diagnoses, such as pneumothorax or pulmonary embolism, which have similar presentations to STEMI ( Deen, 2018 ). Consequently, this hypothesis generation had an element of uncertainty ( Bjørk and Hamilton, 2011 ), which could have impeded Linda's care by erroneously considering only one potential diagnosis and therefore focusing the assessment on that diagnosis. Student nurses can be considered ‘novice’ health professionals, demonstrating limitations in knowledge regarding differential diagnoses and therefore in potential hypotheses. Pearson (2013) argued that this is because student nurses lack the requisite experience to cluster information as effectively as an ‘expert’ health professional. Consequently, the presentation of one hypothesis is permissible within the remits of practice as a student nurse.

Assessment tools such as ABCDE ( Resuscitation Council UK, 2015 ) ensure that all factors indicative of deterioration are recognised. Consequently, by using a systematic assessment, any potential erroneous hypothesis can be precluded. Therefore, as Carayon and Wood (2010) state, the assessment tool was a barrier to active failure to recognise alternative diagnoses thus circumventing any serious consequences, highlighting the importance of comprehensive assessment to avoid error and safeguard the ethical principle of non-maleficence ( Beauchamp and Childress, 2013 ) fundamental to nursing. Antithetically, Benner et al (2008) argued that even the novice nurse should be able to consider multiple hypotheses within a situation, although they may not be able to reflect on these decisions within the moment. However, as Keller (2009) noted, the hypothetico-deductive model is based on presuppositions recognised by the health professional, such as the evolving cardiac tracing and history of pain, indicating that STEMI was the higher probable cause ( Deen, 2018 ). Consequently, a limitation of hypothetico-deductive reasoning is sufficient experience to aid in generating hypotheses.

Thereafter, in the hypothesis generation phase, the decision-making process evolved to include elements of pattern recognition theory ( Croskerry, 2002 ). The clinical decision that focuses on a single hypothesis can be compared to the use of pattern recognition ( Pearson, 2013 ) where existing knowledge is used to establish the hypothesis. Pearson (2013) commented that hypothetico-deductive reasoning is based on the synthesising and analysing of information whereas the formulation of one hypothesis is suggestive of pattern recognition, where the nurse uses previous experience to evaluate the situation. Consequently, the student nurse's previous experience of assessing a patient in acute STEMI may have guided practice to recognise ST-segment elevation on the telemetry, and then subsequently to conduct an ECG, and to recognise the associated clinical signs of STEMI and to gather a history of the pain using NICE (2013b) guidance on unstable angina, in line with Linda's initial presentation. Croskerry (2002) identified that health professionals who rely on pattern recognition initially recognise visual cues that are then supplemented with more in-depth data, often using assessment tools such as NEWS (and now NEWS 2) and ABCDE. Arguably, the recognition of similarities in clinical presentation, past medical history, and cardiac monitoring tracing of Linda's case to the previous case and use of ABCDE and NEWS 2 to further assess her condition and extrapolate data, identifies that previous experience can facilitate decision-making outcomes.

Finally, in the last phase of the decision-making in the hypothetico-deductive model, the student nurse evaluated the hypothesis and by using the merits from the cues ( Banning, 2008 ) established that STEMI was the most probable cause of Linda's deterioration and could escalate her care appropriately using the prescriptive theory tools described above.

Arguably, by using previous experience to guide practice, an element of confirmation bias may have affected the selection of data ( Thompson and Dowding, 2009 ) and consequently the student may have neglected other important data ( Croskerry, 2003 ). For instance, student nurses are inexperienced with chest auscultation and consequently could not have ruled out differential respiratory diagnoses. Stanovich et al (2013) acknowledged that confirmation bias can be circumvented when evidence is assimilated with hypothesis generation. The consideration that Linda may have been at an increased risk of myocardial infarction due to her age, history of smoking and admission to hospital for unstable angina ( Piepoli et al, 2016 ), indicated that the cause of her deterioration would most likely be cardiac. Thus, an evidence-based approach could inform practice and consequently, any limitations as a ‘novice’ would be minimised through rationalisation and critical thinking. Indeed, Stanovich et al (2013) argued that rationalising and critical thinking are markedly more important than existing knowledge. This is because even an ‘expert’ in a specific field does not have completely comprehensive knowledge, and therefore relies on a critical thought process to make rational decisions.

Conclusively, health professionals must be able to rationalise their decisions ( Johansen and O'Brien, 2016 ) and justify these decisions within the context of each presentation as a central concept of nursing ( NMC, 2018 ).

Communication is vital to establishing consent to treatment where the patient is regarded as having capacity under the Mental Capacity Act 2005. This is particularly significant when conducting investigations and escalating care to ensure that the patient's wishes are respected, and that the patient is empowered with knowledge regarding their condition and care ( Coultier and Collins, 2011 ). Linda was informed that her care required escalation to the appropriate clinical team, and then subsequently recommended to have PCI intervention as the most effective treatment for STEMI ( NICE, 2013a ; 2014 ). Presenting a default decision and using choice architecture can be construed as methods of liberal paternalism used to avoid impeded decision-making from choice overload ( Rosenbaum, 2015 ) or irrational decision bias ( Marewski and Gigerenzer, 2012 ). To escalate Linda's care within the recommended timeframe ( NICE, 2013a ; 2014 ), it was important to use elements of liberal paternalism ( Beauchamp and Childress, 2013 ) while preserving Linda's autonomy of choice ( Kemmerer et al, 2017 ). Linda had a right to make a decision against medical advice as per Re B (Adult, refusal of medical treatment) [2002] and these choices were presented to her by the cardiology team. As a health professional, a duty of care was owed to the patient to escalate concerns regarding her condition under the Code ( NMC, 2018 ).

Conclusively, all three theories of decision-making pertained to this patient's effective care. Nurses must be accountable for their decisions and act within the remits of the NMC (2018) Code. Patient care must consequently be effective, evidence-based and patient-centred. Accountability requires the health professional to act within the remits of their role to ensure safe care is delivered to the patient. This is a fundamental aspect of patient-centric care and principal to effective decision making. Demonstrably, the use of descriptive and normative theories can be interchangeable, however, the use of prescriptive theory is pivotal to validate clinical decision-making. The decision-making process can be further facilitated by use of structured assessment tools to reduce margin of error and improve outcome. Collaborative decision making is pivotal to advancing patient autonomy and empowerment but certain decisions require elements of paternalism to improve the process and uphold the ethical principles of beneficence and non-maleficence. Nevertheless, health professionals have a duty of care to adhere to decisions made by patients established to have capacity to give informed consent, irrespective of the personal beliefs of the professional.

- This article is a reflection on a case scenario where decisions were made in the care of a patient admitted for cardiac monitoring

- Nursing decision making is complex and involves a multitude of processes based on experience, knowledge and skill.

- Understanding the importance of decision-making theory and how these theories apply to practice can be effective in reflecting on practice, and the application of theory to practice can inform patient care

CPD reflective questions

- Consider the three different theories of decision making outlined here—which theory do you deem the most important to your practice? How does this affect your practice?

- Consider how reflecting on your own decision making can improve practice

- What can you do to enrich your own knowledge regarding patients with chest pain?

COMMENTS

Critical analysis involves the examination of knowledge that underpins practice. Critical action requires nurses to assess their skills and identify potential gaps in need of professional development.

Based on selective analysis of the descriptive and empirical literature that addresses conceptual review of critical thinking, we conducted an analysis of this topic in the settings of clinical practice, training and research from the virtue ethical framework.

This article outlines a stepwise approach to critical appraisal of research studies' worth to clinical practice: rapid critical appraisal, evaluation, synthesis, and recommendation. When critical care nurses apply a body of valid, reliable, and applicable evidence to daily practice, patient outcomes are improved.

The nursing process becomes a road map for the actions and interventions that nurses implement to optimize their patients’ well-being and health. This chapter will explain how to use the nursing process as standards of professional nursing practice to provide safe, patient-centered care.

The nurse uses critical thinking to examine and interpret the data, separating the relevant from the irrelevant and clarifying the meaning when necessary. During the diagnosis phase, nurses use the diagnostic reasoning process to draw conclusions and decide whether nursing intervention is indicated.

The explosion of clinical research evidence has placed new demands on nurse practitioners (NPs) to critically appraise the abundance of research evidence and clinical practice guidelines to make astute decisions on the implementation of the best available evidence to clinical practice.

Critical thinking (CT) is considered to be a crucial element for clinical decision-making by nurses, and improved empowerment to engage in CT is considered to be a core program outcome in nursing education.

Abstract. Clinical reasoning is a multi-faceted and complex construct, the understanding of which has emerged from multiple fields outside of healthcare literature, primarily the psychological and behavioural sciences.

Evidence-based nursing draws upon critical reasoning and judgment skills developed through experience and training. You can practice evidence-based nursing interventions by following five crucial steps that serve as guidelines for making patient care decisions.

Decision-making is a fundamental concept of nursing practice that conforms to a systematic trajectory involving the assessment, interpretation, evaluation and management of patient-specific situations (Dougherty et al, 2015).