Recent Advances

ADA-funded researchers use the money from their awards to conduct critical diabetes research. In time, they publish their findings in order to inform fellow scientists of their results, which ensures that others will build upon their work. Ultimately, this cycle drives advances to prevent diabetes and to help people burdened by it. In 2018 alone, ADA-funded scientists published over 200 articles related to their awards!

Identification of a new player in type 1 diabetes risk

Type 1 diabetes is caused by an autoimmune attack of insulin-producing beta-cells. While genetics and the environment are known to play important roles, the underlying factors explaining why the immune system mistakenly recognize beta-cells as foreign is not known. Now, Dr. Delong has discovered a potential explanation. He found that proteins called Hybrid Insulin Peptides (HIPs) are found on beta-cells of people with type 1 diabetes and are recognized as foreign by their immune cells. Even after diabetes onset, immune cells are still present in the blood that attack these HIPs.

Next, Dr. Delong wants to determine if HIPs can serve as a biomarker or possibly even targeted to prevent or treat type 1 diabetes. Baker, R. L., Rihanek, M., Hohenstein, A. C., Nakayama, M., Michels, A., Gottlieb, P. A., Haskins, K., & Delong, T. (2019). Hybrid Insulin Peptides Are Autoantigens in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes , 68 (9), 1830–1840.

Understanding the biology of body-weight regulation in children

Determining the biological mechanisms regulating body-weight is important for preventing type 2 diabetes. The rise in childhood obesity has made this even more urgent. Behavioral studies have demonstrated that responses to food consumption are altered in children with obesity, but the underlying biological mechanisms are unknown. This year, Dr. Schur tested changes in brain and hormonal responses to a meal in normal-weight and obese children. Results from her study show that hormonal responses in obese children are normal following a meal, but responses within the brain are reduced. The lack of response within the brain may predispose them to overconsumption of food or difficulty with weight-loss.

With this information at hand, Dr. Schur wants to investigate how this information can be used to treat obesity in children and reduce diabetes.

Roth, C. L., Melhorn, S. J., Elfers, C. T., Scholz, K., De Leon, M. R. B., Rowland, M., Kearns, S., Aylward, E., Grabowski, T. J., Saelens, B. E., & Schur, E. A. (2019). Central Nervous System and Peripheral Hormone Responses to a Meal in Children. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism , 104 (5), 1471–1483.

A novel molecule to improve continuous glucose monitoring

To create a fully automated artificial pancreas, it is critical to be able to quantify blood glucose in an accurate and stable manner. Current ways of continuously monitoring glucose are dependent on the activity of an enzyme which can change over time, meaning the potential for inaccurate readings and need for frequent replacement or calibration. Dr. Wang has developed a novel molecule that uses a different, non-enzymatic approach to continuously monitor glucose levels in the blood. This new molecule is stable over long periods of time and can be easily integrated into miniaturized systems.

Now, Dr. Wang is in the process of patenting his invention and intends to continue research on this new molecule so that it can eventually benefit people living with diabetes.

Wang, B. , Chou, K.-H., Queenan, B. N., Pennathur, S., & Bazan, G. C. (2019). Molecular Design of a New Diboronic Acid for the Electrohydrodynamic Monitoring of Glucose. Angewandte Chemie (International Ed. in English) , 58 (31), 10612–10615.

Addressing the legacy effect of diabetes

Several large clinical trials have demonstrated the importance of tight glucose control for reducing diabetes complications. However, few studies to date have tested this in the real-world, outside of a controlled clinical setting. In a study published this year, Dr. Laiteerapong found that indeed in a real-world setting, people with lower hemoglobin A1C levels after diagnosis had significantly lower vascular complications later on, a phenomenon known as the ‘legacy effect’ of glucose control. Her research noted the importance of early intervention for the best outcomes, as those with the low A1C levels just one-year after diagnosis had significantly lower vascular disease risk compared to people with higher A1C levels.

With these findings in hand, physicians and policymakers will have more material to debate and determine the best course of action for improving outcomes in people newly diagnosed with diabetes.

Laiteerapong, N. , Ham, S. A., Gao, Y., Moffet, H. H., Liu, J. Y., Huang, E. S., & Karter, A. J. (2019). The Legacy Effect in Type 2 Diabetes: Impact of Early Glycemic Control on Future Complications (The Diabetes & Aging Study). Diabetes Care , 42 (3), 416–426.

A new way to prevent immune cells from attacking insulin-producing beta-cells

Replacing insulin-producing beta-cells that have been lost in people with type 1 diabetes is a promising strategy to restore control of glucose levels. However, because the autoimmune disease is a continuous process, replacing beta-cells results in another immune attack if immunosorbent drugs are not used, which carry significant side-effects. This year, Dr. Song reported on the potential of an immunotherapy he developed that prevents immune cells from attacking beta-cells and reduces inflammatory processes. This immunotherapy offers several potential benefits, including eliminating the need for immunosuppression, long-lasting effects, and the ability to customize the treatment to each patient.

The ability to suppress autoimmunity has implications for both prevention of type 1 diabetes and improving success rates of islet transplantation.

Haque, M., Lei, F., Xiong, X., Das, J. K., Ren, X., Fang, D., Salek-Ardakani, S., Yang, J.-M., & Song, J . (2019). Stem cell-derived tissue-associated regulatory T cells suppress the activity of pathogenic cells in autoimmune diabetes. JCI Insight , 4 (7).

A new target to improve insulin sensitivity

The hormone insulin normally acts like a ‘key’, traveling through the blood and opening the cellular ‘lock’ to enable the entry of glucose into muscle and fat cells. However, in people with type 2 diabetes, the lock on the cellular door has, in effect, been changed, meaning insulin isn’t as effective. This phenomenon is called insulin resistance. Scientists have long sought to understand what causes insulin resistance and develop therapies to enable insulin to work correctly again. This year, Dr. Summers determined an essential role for a molecule called ceramides as a driver of insulin resistance in mice. He also presented a new therapeutic strategy for lowering ceramides and reversing insulin resistance. His findings were published in one of the most prestigious scientific journals, Science .

Soon, Dr. Summers and his team will attempt to validate these findings in humans, with the ultimate goal of developing a new medication to help improve outcomes in people with diabetes.

Chaurasia, B., Tippetts, T. S., Mayoral Monibas, R., Liu, J., Li, Y., Wang, L., Wilkerson, J. L., Sweeney, C. R., Pereira, R. F., Sumida, D. H., Maschek, J. A., Cox, J. E., Kaddai, V., Lancaster, G. I., Siddique, M. M., Poss, A., Pearson, M., Satapati, S., Zhou, H., … Summers, S. A. (2019). Targeting a ceramide double bond improves insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis. Science (New York, N.Y.) , 365 (6451), 386–392.

Determining the role of BPA in type 2 diabetes risk

Many synthetic chemicals have infiltrated our food system during the period in which rates of diabetes has surged. Data has suggested that one particular synthetic chemical, bisphenol A (BPA), may be associated with increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes. However, no study to date has determined whether consumption of BPA alters the progression to type 2 diabetes in humans. Results reported this year by Dr. Hagobian demonstrated that indeed when BPA is administered to humans in a controlled manner, there is an immediate, direct effect on glucose and insulin levels.

Now, Dr. Hagobian wants to conduct a larger clinical trial including exposure to BPA over a longer period of time to determine precisely how BPA influences glucose and insulin. Such results are important to ensure the removal of chemicals contributing to chronic diseases, including diabetes.

Hagobian, T. A. , Bird, A., Stanelle, S., Williams, D., Schaffner, A., & Phelan, S. (2019). Pilot Study on the Effect of Orally Administered Bisphenol A on Glucose and Insulin Response in Nonobese Adults. Journal of the Endocrine Society , 3 (3), 643–654.

Investigating the loss of postmenopausal protection from cardiovascular disease in women with type 1 diabetes

On average, women have a lower risk of developing heart disease compared to men. However, research has shown that this protection is lost in women with type 1 diabetes. The process of menopause increases rates of heart disease in women, but it is not known how menopause affects women with type 1 diabetes in regard to risk for developing heart disease. In a study published this year, Dr. Snell-Bergeon found that menopause increased risk markers for heart disease in women with type 1 diabetes more than women without diabetes.

Research has led to improved treatments and significant gains in life expectancy for people with diabetes and, as a result, many more women are reaching the age of menopause. Future research is needed to address prevention and treatment options.

Keshawarz, A., Pyle, L., Alman, A., Sassano, C., Westfeldt, E., Sippl, R., & Snell-Bergeon, J. (2019). Type 1 Diabetes Accelerates Progression of Coronary Artery Calcium Over the Menopausal Transition: The CACTI Study. Diabetes Care , 42 (12), 2315–2321.

Identification of a potential therapy for diabetic neuropathy related to type 1 and type 2 diabetes

Diabetic neuropathy is a type of nerve damage that is one of the most common complications affecting people with diabetes. For some, neuropathy can be mild, but for others, it can be painful and debilitating. Additionally, neuropathy can affect the spinal cord and the brain. Effective clinical treatments for neuropathy are currently lacking. Recently, Dr. Calcutt reported results of a new potential therapy that could bring hope to the millions of people living with diabetic neuropathy. His study found that a molecule currently in clinical trials for the treatment of depression may be valuable for diabetic neuropathy, particularly the type affecting the brain.

Because the molecule is already in clinical trials, there is the potential that it can benefit patients sooner than later.

Jolivalt, C. G., Marquez, A., Quach, D., Navarro Diaz, M. C., Anaya, C., Kifle, B., Muttalib, N., Sanchez, G., Guernsey, L., Hefferan, M., Smith, D. R., Fernyhough, P., Johe, K., & Calcutt, N. A. (2019). Amelioration of Both Central and Peripheral Neuropathy in Mouse Models of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes by the Neurogenic Molecule NSI-189. Diabetes , 68 (11), 2143–2154.

ADA-funded researcher studying link between ageing and type 2 diabetes

One of the most important risk factors for developing type 2 diabetes is age. As a person gets older, their risk for developing type 2 diabetes increases. Scientists want to better understand the relationship between ageing and diabetes in order to determine out how to best prevent and treat type 2 diabetes. ADA-funded researcher Rafael Arrojo e Drigo, PhD, from the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, is one of those scientists working hard to solve this puzzle.

Recently, Dr. Arrojo e Drigo published results from his research in the journal Cell Metabolism . The goal of this specific study was to use high-powered microscopes and novel cellular imaging tools to determine the ‘age’ of different cells that reside in organs that control glucose levels, including the brain, liver and pancreas. He found that, in mice, the cells that make insulin in the pancreas – called beta-cells – were a mosaic of both old and young cells. Some beta-cells appeared to be as old as the animal itself, and some were determined to be much younger, indicating they recently underwent cell division.

Insufficient insulin production by beta-cells is known to be a cause of type 2 diabetes. One reason for this is thought to be fewer numbers of functional beta-cells. Dr. Arrojo e Drigo believes that people with or at risk for diabetes may have fewer ‘young’ beta-cells, which are likely to function better than old ones. Alternatively, if we can figure out how to induce the production of younger, high-functioning beta-cells in the pancreas, it could be a potential treatment for people with diabetes.

In the near future, Dr. Arrojo e Drigo’s wants to figure out how to apply this research to humans. “The next step is to look for molecular or morphological features that would allow us to distinguish a young cell from and old cell,” Dr. Arrojo e Drigo said.

The results from this research are expected to provide a unique insight into the life-cycle of beta-cells and pave the way to novel therapeutic avenues for type 2 diabetes.

Watch a video of Dr. Arrojo e Drigo explaining his research!

Arrojo E Drigo, R. , Lev-Ram, V., Tyagi, S., Ramachandra, R., Deerinck, T., Bushong, E., … Hetzer, M. W. (2019). Age Mosaicism across Multiple Scales in Adult Tissues. Cell Metabolism , 30 (2), 343-351.e3.

Researcher identifies potential underlying cause of type 1 diabetes

Type 1 diabetes occurs when the immune system mistakenly recognizes insulin-producing beta-cells as foreign and attacks them. The result is insulin deficiency due to the destruction of the beta-cells. Thankfully, this previously life-threatening condition can be managed through glucose monitoring and insulin administration. Still, therapies designed to address the underlying immunological cause of type 1 diabetes remain unavailable.

Conventional approaches have focused on suppressing the immune system, which has serious side effects and has been mostly unsuccessful. The American Diabetes Association recently awarded a grant to Dr. Kenneth Brayman, who proposed to take a different approach. What if instead of suppressing the whole immune system, we boost regulatory aspects that already exist in the system, thereby reigning in inappropriate immune cell activation and preventing beta-cell destruction? His idea focused on a molecule called immunoglobulin M (IgM), which is responsible for limiting inflammation and regulating immune cell development.

In a paper published in the journal Diabetes , Dr. Brayman and a team of researchers reported exciting findings related to this approach. They found that supplementing IgM obtained from healthy mice into mice with type 1 diabetes selectively reduced the amount of autoreactive immune cells known to target beta-cells for destruction. Amazingly, this resulted in reversal of new-onset diabetes. Importantly, the authors of the study determined this therapy is translatable to humans. IgM isolated from healthy human donors also prevented the development of type 1 diabetes in a humanized mouse model of type 1 diabetes.

The scientists tweaked the original experiment by isolating IgM from mice prone to developing type 1 diabetes, but before it actually occurred. When mice with newly onset diabetes were supplemented with this IgM, their diabetes was not reversed. This finding suggests that in type 1 diabetes, IgM loses its capacity to serve as a regulator of immune cells, which may be contribute to the underlying cause of the disease.

Future studies will determine exactly how IgM changes its regulatory properties to enable diabetes development. Identification of the most biologically optimal IgM will facilitate transition to clinical applications of IgM as a potential therapeutic for people with type 1 diabetes. Wilson, C. S., Chhabra, P., Marshall, A. F., Morr, C. V., Stocks, B. T., Hoopes, E. M., Bonami, R.H., Poffenberger, G., Brayman, K.L. , Moore, D. J. (2018). Healthy Donor Polyclonal IgM’s Diminish B Lymphocyte Autoreactivity, Enhance Treg Generation, and Reverse T1D in NOD Mice. Diabetes .

ADA-funded researcher designs community program to help all people tackle diabetes

Diabetes self-management and support programs are important adjuncts to traditional physician directed treatment. These community-based programs aim to give people with diabetes the knowledge and skills necessary to effectively self-manage their condition. While several clinical trials have demonstrated the value of diabetes self-management programs in terms of improving glucose control and reducing health-care costs, whether this also occurs in implemented programs outside a controlled setting is unclear, particularly in socially and economically disadvantaged groups.

Lack of infrastructure and manpower are often cited as barriers to implementation of these programs in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities. ADA-funded researcher Dr. Briana Mezuk addressed this challenge in a study recently published in The Diabetes Educator . Dr. Mezuk partnered with the YMCA to evaluate the impact of the Diabetes Control Program in Richmond, Virginia. This community-academic partnership enabled both implementation and evaluation of the Diabetes Control Program in socially disadvantaged communities, who are at higher risk for developing diabetes and the complications that accompany it.

Dr. Mezuk had two primary research questions: (1) What is the geographic and demographic reach of the program? and (2) Is the program effective at improving diabetes management and health outcomes in participants? Over a 12-week study period, Dr. Mezuk found that there was broad geographic and demographic participation in the program. The program had participants from urban, suburban and rural areas, most of which came from lower-income zip codes. HbA1C, mental health and self-management behaviors all improved in people taking part in the Greater Richmond Diabetes Control Program. Results from this study demonstrate the value of diabetes self-management programs and their potential to broadly improve health outcomes in socioeconomically diverse communities. Potential exists for community-based programs to address the widespread issue of outcome disparities related to diabetes. Mezuk, B. , Thornton, W., Sealy-Jefferson, S., Montgomery, J., Smith, J., Lexima, E., … Concha, J. B. (2018). Successfully Managing Diabetes in a Community Setting: Evidence from the YMCA of Greater Richmond Diabetes Control Program. The Diabetes Educator , 44 (4), 383–394.

Using incentives to stimulate behavior changes in youth at risk for developing diabetes

Once referred to as ‘adult-onset diabetes’, incidence of type 2 diabetes is now rapidly increasing in America’s youth. Unfortunately, children often do not have the ability to understand how everyday choices impact their health. Could there be a way to change a child’s eating behaviors? Davene Wright, PhD, of Seattle Children’s Hospital was granted an Innovative Clinical or Translational Science award to determine whether using incentives, directed by parents, can improve behaviors related to diabetes risk. A study published this year in Preventive Medicine Reports outlined what incentives were most desirable and feasible to implement. A key finding was that incentives should be tied to behavior changes and not to changes in body-weight.

With this information in hand, Dr. Wright now wants to see if incentives do indeed change a child’s eating habits and risk for developing type 2 diabetes. She is also planning to test whether an incentive program can improve behavior related to diabetes management in youth with type 1 diabetes. Jacob-Files, E., Powell, J., & Wright, D. R. (2018). Exploring parent attitudes around using incentives to promote engagement in family-based weight management programs. Preventive Medicine Reports , 10 , 278–284.

Determining the genetic risk for gestational diabetes

Research has identified more than 100 genetic variants linked to risk for developing type 2 diabetes in humans. However, the extent to which these same genetic variants might affect a woman’s probability for getting gestational diabetes has not been investigated.

Pathway to Stop Diabetes ® Accelerator awardee Marie-France Hivert, MD, of Harvard University set out to answer this critical question. Dr. Hivert found that indeed genetic determinants of type 2 diabetes outside of pregnancy are also strong risk factors for gestational diabetes. This study was published in the journal Diabetes .

The implications? Because of this finding, doctors in the clinic may soon be able to identify women at risk for getting gestational diabetes and take proactive steps to prevent it. Powe, C. E., Nodzenski, M., Talbot, O., Allard, C., Briggs, C., Leya, M. V., … Hivert, M.-F. (2018). Genetic Determinants of Glycemic Traits and the Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes , 67 (12), 2703–2709.

Give Today and Change lives!

With your support, the American Diabetes Association® can continue our lifesaving work to make breakthroughs in research and provide people with the resources they need to fight diabetes.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

New insights into diabetes mellitus and its complications: a narrative review

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence to: Prof. Fei Hua, MD, PhD. Department of Endocrinology, the Third Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Changzhou, China. Email: [email protected] .

Corresponding author.

Received 2020 Aug 6; Accepted 2020 Dec 16; Issue date 2020 Dec.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 .

Diabetes is a metabolic disorder accompanied by complications of multiple organs and systems. Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is one of the most prevalent lethal complications of diabetes. Although numerous biomarkers have be clarified for early diagnosis of DN, renal biopsy is still the gold standard. As a noninvasive imaging diagnostic method, blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) MRI can help understand the kidney oxygenation status and fibrosis process and monitor the efficacy of new drugs for DN via monitoring renal blood oxygen levels. Recent studies have shown that noncoding RNAs including microRNAs (miRNAs), long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) and circular RNAs (circRNAs) were all involved in the development of DN, which could be exploited as therapeutic strategy to control DN. Dyslipidemia is also a common complication of diabetes. Apolipoprotein M (apoM), as a novel apolipoprotein, may be related to the development and progression of diabetes, which need to further investigation. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is another common complication of diabetes and is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). At present, there is no simple, effective and rapid diagnostic method to early identification of OSA in patients with diabetes. A nomogram consisted of waist-to-hip ratio, smoking status, body mass index, serum uric acid, HOMA-IR and history of fatty liver might be an alternative method to early assess the risk of OSA.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus (DM), diabetic nephropathy (DN), dyslipidemia, apolipoprotein M (apoM), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM), as a growing epidemic of bipolar disorder, affects near 5.6% of the world’s population ( 1 ). Its global prevalence was about 8% in 2011 and is predicted to rise to 10% by 2030 ( 2 ). Likewise, its prevalence in China also increased rapidly from 0.67% in 1980 to 10.4% in 2013 ( 3 ). Therefore, DM is a contributing factor to morbidity and mortality. So far, various organizations have developed various diabetic guidelines to clarify the definition, classification, diagnosis, screening, and prevention of this disease, which are used not for clinical management but also the monitoring of ongoing care with laboratory check-ups at regular intervals, lifestyle counseling, and prevention of diabetic-related complications.

The diagnostic criteria for DM are based primarily on fasting plasma glucose (FPG), random plasma glucose or oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) 2-hour plasma glucose (2hPG). In 2011, WHO recommended wherever conditions permit, countries and regions may consider adopting the hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥6.5% as the cut-point for a diabetes diagnosis. Several studies have shown that the optimal cut-off value for HbA1c to diagnose diabetes in Chinese adults is 6.3%. However, HbA1c has not yet been included in the latest guidelines for diabetes in China ( 3 ).

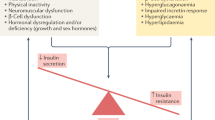

DM is classified into four types: type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), T2DM, other specific types of diabetes, and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), whereas T2DM is the most common form and occurs when the target tissue (the liver, skeletal muscles, and adipose tissues) loses insulin sensitivity. In the United States, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) guidelines, and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and the American College of Endocrinology (ACE) guidelines are two typically consulted to determine optimal therapeutic decisions in patients with T2DM. The differences between the two guidelines are: (I) the ADA/EASD guideline advocates a stepwise approach to glycemic control, starting with metformin and incrementally intensifying to dual and triple therapy at 3-month intervals until the patient is at their individualized goal, whereas the AACE/ACE guideline provides a broader choice of first-line medications, with a suggested hierarchy of use. It encourages initial dual and triple therapy if the HbA1c level is 7.59.0% and >9.0% at diagnosis, respectively. (II) Compared with the value in the AACE/ACE guideline, the target HbA1c value is higher in the ADA/EASD guideline (≤6.5% vs . ≤7.0%) ( 4 ). Considering the ethnic characteristics, social culture, and social resources, the Chinese Diabetes Society (CDS) has drawn up the latest version of guidelines for the prevention and care of T2DM in China in 2019, which may work best for the Chinese patient population. This guideline recommends the target HbA1c value, which is <7% for most nonpregnant adults with T2DM, and drug therapy should be started when HbA1c value is ≥7.0%. Metformin, α-glucosidase inhibitors, or insulin secretagogues could be options for monotherapy. If monotherapy is insufficient, dual and triple therapy or multiple daily insulin injections may be prescribed ( 3 ). Diabetes is a complicated disease that affects multiple organs, requiring multiple treatments and preventive strategies to prevent long-term complications associated with it. The following is a brief narrative review of the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of diabetic complications. MEDLINE was searched using the terms “diabetic nephropathy”, “diabetes and dyslipidemia”, “Apolipoprotein M”, “diabetes and obstructive sleep apnea” for nearly five years.

We present the following article in accordance with the Narrative Review reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-7243 ).

Diabetic nephropathy (DN)

DN, as one of the most prevalent lethal complications of diabetes, is observed in approximately 20% to 30% of T2DM individuals ( 5 ). The etiology of DN is multi-factor and involves many molecular signaling pathway abnormalities, including the advanced glycation end products/receptors for AGE (AGE/RAGE), protein kinase C (PKC), reactive oxygen species (ROS), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), Janus Kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription Proteins (JAK/STAT), etc. ( 6 ). Chronic hypoxia is one feature of DN. At present, the clinical diagnosis of DN mainly depends on the elevated urinary albumin excretion and reduced eGFR in the absence of other primary causes of kidney damage, lacking high sensitivity and specificity indicators to reflect the renal blood oxygen levels. A growing number of studies have focused on the biomarkers for early diagnosis of DN, which include (I) certain urinary microRNAs such as microRNA-210 and microRNA-34a ( 7 ), urinary kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1) and Chitinase-3-like protein 1 (YKL-40) ( 8 ), urinary E-cadherin ( 9 ); (II) serum galectin-3 and growth differentiation factor-15 (GDF-15) ( 10 ), serum pregnenolone sulfate, ganglioside GA1, phosphatidyl glycerol and all-trans-Carophyll yellow tested by direct flow through mass spectrometry ( 11 ); (III) suppressor of mothers against decapentaplegic type 1 (SMAD1) and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) gene expression in peripheral blood and urine samples ( 12 ). However, renal biopsy is still the gold standard to diagnose diabetic nephropathy. Tong et al. have searched identified 40 studies worldwide between 1977 and 2019 that looked at global renal biopsy and pathological nondiabetic kidney disease (NDKD) lesions. The results have shown that overall prevalence rate of DN, NDKD and DN plus NDKD is 41.3, 40.6 and 18.1%, respectively ( 13 ). Therefore, it is of great significance to do renal biopsy as early as possible to confirm the diagnosis and to enable personalized treatment especially when T2DM patients present atypical diabetic kidney disease (DKD) symptoms (e.g., absence of diabetic retinopathy, shorter duration of diabetes, microscopic hematuria, subnephrotic range proteinuria, lower glycated hemoglobin, lower fasting blood glucose). Ding et al. have shown that texture analysis with DWI, BOLD, and susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) can help assess renal dysfunction during the early stages of chronic kidney disease ( 14 ). Jiang et al. reported the role of SWI parameters and SWI-based texture features in evaluating renal dysfunction of T2DM ( 15 ). They showed that the signal intensity ratio of the medulla to psoas muscle (MPswi) was significantly lower than the signal intensity ratio of the cortex to psoas muscle (CPswi) in non-moderate-severe renal injured (non-msRI) group and msRI group. MPswi was higher, whereas the signal intensity ratio of the cortex to the medulla (CMswi), skewness, the correlation was lower in the msRI group than in non-msRI group and CMswi was an independent protective factor for msRI. These results supply a crucial noninvasive method to monitor renal blood oxygen levels, which can help understand the kidney oxygenation status and fibrosis process and monitor the efficacy of new drugs for DN. As a noninvasive imaging diagnostic method, MRI provides some level of spatial resolution and it can be performed repeatedly, providing some level of temporal resolution. Moreover, it is noninvasive and thus can be applied to both animals used in experiments and humans, providing a pathway for translation of new therapies. So far, blood oxygen level–dependent (BOLD) MRI, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) MRI and dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) MRI have been confirmed to be used for early identification of DN. A major advantage of BOLD-MRI is that it does not require an exogenous paramagnetic agent, because it relies on the differing paramagnetic properties of oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin. BOLD imaging detected the medullary hypoxia at the simply diabetic stage, while DTI didn’t identify the medullary directional diffusion changes at this stage. Therefore, BOLD imaging may be more sensitive for assessment of the early renal function changes than DTI ( 16 ). Furthermore, BOLD-MRI, coupled with other imaging modalities that provide information about renal hemodynamics and function, has provided important insights into the temporal and spatial relationships between renal hypoxia and progression of diabetic nephropathy ( 17 ). However, there are several disadvantages of BOLD-MRI. First, BOLD-MRI provides a measure of blood oxygenation rather than tissue oxygenation. Second, it is not quantitative in the sense that it cannot provide an actual level of PO 2 or even of blood hemoglobin saturation. Third, it is susceptible to artefacts caused by changes in renal blood volume and hemoglobin concentration. DNP-MRI combined with the oxygen-sensitive paramagnetic agent OX63 ( 18 ) is a method for quantifying tissue oxygen tension within the kidney. Nevertheless, this method needs to use an exogenous paramagnetic agent that must be administered intravenously and OX63 is also rather expensive. Therefore, it is used only in small animals such as the mice. Furthermore, either general anesthesia or physical restraint is required during imaging.

Although several clinical approaches are available to relieve symptoms temporarily or impede the progression of DN, there is no curative treatment to date. Therefore, a novel therapeutic strategy is warranted to control DN. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of non-coding RNAs that can bind to their target mRNAs to take part in the epigenetic machinery of their downstream signaling molecules. Over the past few decades, a plethora of studies has revealed the potential involvement of different miRNAs in different molecular and signaling pathways leading to DN. Several reviews and studies have shown in-depth the vital role of various miRNAs in progression, diagnosis, and therapeutics of DN ( 19 ). Concretely speaking, several miRNAs including miR-21, miR-124, miR-135a, miR-192, miR-195, miR-200, miR-215, miR-216a, miR-217, miR-377, and miR-1207-5p, are overexpressed in DN, whereas some miRNAs (Let-7, miR-25, miR-29, miR-93, miR-141, miR-200, and miR-451) are down-regulated ( 20 ). The roles of miRNAs are multifaceted, involved in the TGF-β signaling pathway, in the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, in collagen gene expression, in DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) and so on ( 20 ). Therefore, both up- and down-regulation of DN-suppressing and DN-promoting miRNAs can be exploited as therapeutic interventions in DN, respectively. Pharmacological inhibition of miRNAs can be achieved through employing miRNA inhibitors, anti-miRNA oligonucleotides (AMOs) and miRNA sponges, while up-regulation of miRNAs can be accomplished using miRNA mimics, miRNA-containing exosomes and miRNA promoters ( 20 ).

Except for the microRNAs (miRNAs), long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) and circular RNAs (circRNAs) are also play an important role in DN progression. Several lncRNAs such as the Plasmacytoma Variant Translocation-1 (PVT1) LncRNA, the Nuclear Enriched Abundant Transcript-1 (NEAT1) LncRNA, LncRNA ERBB4-IR, LncRNA CYP4B1-PS1-001 and LncRNA ENSMUST00000147869 are involved in the regulation of renal hypertrophy and extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulation. A few lncRNAs such as LncRNA GM4419, the Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript-1 (MALAT-1) LncRNA, LncRNA GM6135, myocardial infarction-associated transcript (MIAT) LncRNA can regulate renal inflammation and oxidative stress. Furthermore, LncRNA GM5524, LncRNA GAS5, LncRNA GM15645, the Taurine upregulated-1 (TUG-1) LncRNA and the Cancer susceptibility candidate 2 (CASC2) LncRNA are involved in the renal autophagy and apoptosis ( 21 ). The evidence to elucidate the interaction of circular RNA in DN progression is limited. Only one study in DN mice showed that circRNA_15698 expression could regulate the fibrosis of mesangial cells ( 22 ).

Connexins (Cxs) are a multigenic family of transmembrane proteins that form gap junction membrane channels and take part in the exchange of information between adjacent cells. Cx43 is the most abundantly expressed and widely distributed gap junction protein. A previous study has shown that the expression of Cx43 was significantly decreased in DN patients and diabetic model animals ( 23 ). Other studies have shown that the upregulation of Cx43 was involved in podocyte injury, and the interdependence of Cx43 and impaired autophagic flux may be a novel mechanism of podocyte injury in DN ( 24 , 25 ). Also, one latest research has shown the essential role of Cx43 in regulating renal EMT and diabetic renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis via regulating the SIRT1-HIF-1α signaling pathway and provided an experimental basis for Cx43 as a potential target for DN ( 26 ).

Li et al. put forward a new viewpoint that there was a link between miRNA-30 and Cx43 in the podocyte under high glucose ambiance (HG) or diabetic state ( 27 ). They used streptozotocin (STZ)-induced rat model of diabetes and podocyte culture under HG. Both the podocytes and rats were concomitantly treated with miRNA-30 mimic or miRNA-30 inhibitors. The results showed that the expression of miRNA-30 was down-regulated, and the transfection of miRNA-30 reduced podocyte injury, apoptosis, and ERS, both in vivo and in vitro. Luciferase reporter assays confirmed Cx43 is a directed target of microRNA-30s. Likewise, Cx43 siRNA treatment yielded comparable results. From these results, the authors concluded that the overexpression of miRNA-30 prevents DN-induced podocyte damage by modulating Cx43 expression. This study provides novel information that highlights the microRNA-30/Cx43/ERS axis, plays a role in the pathogenesis of DN, and it may serve as a potential therapeutic target for the amelioration of DN. However, considerable research is needed for a better understanding of the regulation and functions of this signaling pathway in DN.

Diabetes and dyslipidemia

Glucose intolerance, dyslipidemia, combined with abdominal obesity and hypertension, together constitute the metabolic syndrome (MetS), which results in a significant increase in morbidity and all-cause mortality. A 10-year prospective study has shown that MetS could lead to 1.80 and 2.05 times higher statistically significant probability for myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke events, respectively. Further studies have shown that abdominal obesity increases the risk of MI, and low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and hypertriglyceridemia increase the risk of stroke in men with MetS ( 28 ). Dyslipidemia in adolescence is usually associated with one or more components of the MetS, namely obesity, hypertension, and impaired glucose tolerance, and presents with high triglyceride and low HDL-C. In one trial of adolescents with T2DM, 21% had high triglyceride levels or had been treated with lipid-lowering drugs at baseline, and 23% had high triglyceride (TG) levels three years later ( 29 ). It is worth noting that there is increasing evidence linking T2DM to atherosclerosis, which may attribute to local activation of the RAS and its components, including receptors and relevant enzymes in the microvessel ( 30 ). Also, high TG, low HDL-C, increased LDL particle number or apolipoprotein B, smaller LDL size and density, and LDL glycation and oxidation are all associated with increased atherosclerosis ( 31 ). The EVAPORATE trial has revealed HDL-C levels are negatively correlated with baseline coronary plaque, total plaque (TP), and total non-calcified plaque (TNCP) volumes, providing more detailed mechanistic evidence for the protective effect of HDL-C on coronary atherosclerosis in high-risk populations ( 32 ). China’s latest guideline has recommended that the therapeutic targets for lipids are: LDL-C <2.60 mmol/L, TG <1.70 mmol/L, HDL-C ≥1.0 mmol/L, to prevent clinical cardiovascular disease (CVD) ( 3 ). Therefore, treatment measures should be taken when LDL-C, TG, and HDL-C levels exceed cut points in diabetic patients.

Apolipoprotein M (apoM) is a novel apolipoprotein bound primarily to HDL in plasma. Many previous studies have shown that in diabetic mouse models, the expression of apoM in plasma, liver, and kidney is all remarkably decreased, which may be attributed to the decreased expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor and liver X receptor secondary to hyperglycemia ( 33 , 34 ). However, the results of studies on apoM expression in diabetic patients are inconsistent. Several studies have shown that plasma apoM levels decreased significantly in maturity-onset diabetes of the young 3 (MODY3) individuals with HNF-1 mutation, whereas these levels remained unchanged in MODY1 patients ( 35 ). Contradicting results have been reported no significant differences in apoM concentrations among MODY3, T2DM, and healthy individuals ( 36 ). The inconsistency between studies may apply to differences in methods (e.g., dot blot, immunoblot, and ELISA) used to detect serum apoM. Also, previous studies have determined apoM levels were negatively correlated with the development and progression of diabetes, which could be attributed to Sphingosine-1-Phosphate, a functional lipid that can promote β-cell functions, and insulin secretion and improve glucose tolerance ( 37 , 38 ). Finally, genetic variations in the apoM gene have also played a prominent role in diabetes susceptibility. Wu et al. found that SNP T-778C was strongly associated with T1DM in both Han Chinese and Swedish populations, and allele C of SNP T-778C may increase promoter activity and confer the risk susceptibility to the development of T1DM ( 39 ). More recently, a study by Liu et al. suggested that rs805296 (T-778C)-C and rs9404941 (T-855C)-C alleles haplotypes were indicators of high T2DM risk ( 40 ). However, another study drew a different conclusion that there was no association between the apoM gene and T2DM susceptibility in Hong Kong Chinese cohort. Interestingly, the C allele of rs805297 was significantly associated with T2DM duration of longer than ten years ( 41 ). Therefore, the relationship between apoM and diabetes deserves further investigation.

According to the study by Yao et al. ( 42 ), apoM is expressed on all peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Impressively, compared with the other monocytes, CD14 + cells, the central immune cells, in the atherosclerotic process, have the highest rates of apoM+ cells, suggesting that apoM might take part in the pathological lesions of atherosclerosis. The investigators found both apoM + HDL and apoM – HDL could downregulate the expression of IL-6, IL-1β, and MCP-1 in macrophages, and the downregulation of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β was more significant in the apoM + HDL group than in the apoM – HDL group. Notably, the expression of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine preventing lipid deposition and inflammation in atherosclerotic lesions, was significantly upregulated in the apoM + HDL group. In this study, the investigators used coimmunoprecipitation to detect the binding of purified apoM + HDL and apoM – HDL proteins to SR-BI, the physiological receptor for apoA-I/HDL which was expressed on the surface of THP-1 macrophages. The results showed that the recombinant human apoM, human apoM – HDL, and human apoM + HDL particles could interact with SR-BI, highlighting that apoM could promote the anti-inflammatory effects of HDL, possibly by binding to SR-BI. However, further studies are necessary to investigate the downstream signaling pathway.

Diabetes and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)

OSA is characterized by recurrent partial (hypopnea) or complete (apnea) upper airway obstruction, leading to hypoxia, recurrent arousal from sleep, and desaturation-reoxygenation sequences ( 43 ). Data from previous research suggest OSA is associated with many metabolic abnormalities, including impaired fatty acid handling, glucose tolerance, and insulin sensitivity, atherogenesis, and high blood pressure, through the effects of sleep fragmentation, intermittent hypoxia, sympathetic overactivity, and adipose tissue inflammation ( 43 , 44 ). Also, many studies have confirmed that OSA is an independent risk factor for CVD ( 45 ). Notably, a recent study showed that OSA could cause a significant increase in all-cause mortality and major adverse cardiac events (MACEs) in patients with T2DM and co-existing OSA following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) ( 46 ).The investigators proposed several mechanisms by which OSA contributes to cardiovascular events, including endothelial dysfunction, vascular inflammation, and high platelet reactions resulting from intermittent hypoxemia, autonomic imbalance, and sleep disruption ( 47 ). Therefore, early diagnosis and management of OSA might be critical for patients with T2DM to reduce the risk of MACEs.

A study by Shi et al. ( 48 ) constructed and validated an easy-to-use nomogram comprising six items, namely waist-to-hip ratio, smoking status, body mass index, serum uric acid, HOMA-IR and history of fatty liver which could accurately predict and rapidly assess the risk of OSA in patients with T2DM, and help identify patients at high risk of OSA that should be referred for diagnostic polysomnography. This nomogram, as a lesscostly and time-consuming examination, is worthy of clinical promotion to reduce the number of missed OSA diagnoses in patients with T2DM. However, the sensitivity and specificity of this nomogram need further evaluation in the general population.

Conclusions

Diabetes is a metabolic disorder that has resulted in critical personal health hazards and public severe health burdens worldwide, often accompanied by chronic systemic complications in multiple organs and systems, including diabetic nephropathy, diabetic retinopathy, diabetic neuropathy, and so on. Moreover, diabetes is associated with metabolic syndrome and OSA. Simple and easy detection methods with high sensitivity are conducive to the early diagnosis of diabetic complications. Clarifying the mechanism of diabetic complications is conducive to develop new drugs and therapies.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: None

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Reporting Checklist: The author was completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-7243

Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-7243 ). The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

(English Language Editor: J. Chapnick)

- 1. AghaeiZarch SM , DehghanTezerjani M, Talebi M, et al. Molecular biomarkers in diabetes mellitus (DM). Med J Islam Repub Iran 2020;34:28. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Hashmi NR, Khan SA. Adherence To Diabetes Mellitus Treatment Guidelines From Theory To Practice: The Missing Link. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2016;28:802-8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Jia W, Weng J, Zhu D, et al. Standards of medical care for type 2 diabetes in China 2019. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2019;35:e3158. 10.1002/dmrr.3158 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Cornell S. Comparison of the diabetes guidelines from the ADA/EASD and the AACE/ACE. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2017;57:261-5. 10.1016/j.japh.2016.11.005 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Holt RIG. Lest we forget the microvascular complications of diabetes. Diabet Med 2018;35:1307. 10.1111/dme.13807 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Meza Letelier CE, San Martín Ojeda CA, Ruiz Provoste JJ, et al. Pathophysiology of diabetic nephropathy: a literature review. Medwave 2017;17:e6839. 10.5867/medwave.2017.01.6839 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Nossier AI, Shehata NI, Morsy SM, et al. Determination of certain urinary microRNAs as promising biomarkers in diabetic nephropathy patients using gold nanoparticles. Anal Biochem 2020;609:113967. 10.1016/j.ab.2020.113967 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Kapoula GV, Kontou PI, Bagos PG. Diagnostic Performance of Biomarkers Urinary KIM-1 and YKL-40 for Early Diabetic Nephropathy, in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10:909. 10.3390/diagnostics10110909 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Koziolek M, Mueller GA, Dihazi GH, et al. Urine E-cadherin: A Marker for Early Detection of Kidney Injury in Diabetic Patients. J Clin Med 2020;9:639. 10.3390/jcm9030639 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Hussain S, Habib A, Hussain MS, et al. Potential biomarkers for early detection of diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2020;161:108082. 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108082 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Nilavan E, Sundar S, Shenbagamoorthy M, et al. Identification of biomarkers for early diagnosis of diabetic nephropathy disease using direct flow through mass spectrometry. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020;14:2073-8. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.10.017 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Veiga G, Alves B, Perez M, et al. NGAL and SMAD1 gene expression in the early detection of diabetic nephropathy by liquid biopsy. J Clin Pathol 2020;73:713-21. 10.1136/jclinpath-2020-206494 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Tong X, Yu Q, Ankawi G, et al. Insights into the Role of Renal Biopsy in Patients with T2DM: A Literature Review of Global Renal Biopsy Results. Diabetes Ther 2020;11:1983-99. 10.1007/s13300-020-00888-w [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Ding J, Xing Z, Jiang Z, et al. Evaluation of renal dysfunction using texture analysis based on DWI, BOLD, and susceptibility-weighted imaging. Eur Radiol 2019;29:2293-301. 10.1007/s00330-018-5911-3 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Jiang Z, Wang Y, Ding J, et al. Susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) for evaluating renal dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a preliminary study using SWI parameters and SWI-based texture features. Ann Transl Med 2020;8:1673. 10.21037/atm-20-7121 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Feng YZ, Ye YJ, Cheng ZY, et al. Non-invasive assessment of early stage diabetic nephropathy by DTI and BOLD MRI. Br J Radiol 2020;93:20190562. 10.1259/bjr.20190562 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Evans RG. Another step forward for methods for studying renal oxygenation. Kidney Int 2019;96:552-4. 10.1016/j.kint.2019.05.010 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Kodama Y, Hyodo F, Yamato M, et al. Dynamic nuclear polarization magnetic resonance imaging and the oxygen-sensitive paramagnetic agent OX63 provide a noninvasive quantitative evaluation of kidney hypoxia in diabetic mice. Kidney Int 2019;96:787-92. 10.1016/j.kint.2019.04.034 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Sankrityayan H, Kulkarni YA, Gaikwad AB. Diabetic nephropathy: The regulatory interplay between epigenetics and microRNAs. Pharmacol Res 2019;141:574-85. 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.01.043 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Dewanjee S, Bhattacharjee N. MicroRNA: A new generation therapeutic target in diabetic nephropathy. Biochem Pharmacol 2018;155:32-47. 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.06.017 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Loganathan TS, Sulaiman SA, Abdul Murad NA, et al. Interactions Among Non-Coding RNAs in Diabetic Nephropathy. Front Pharmacol 2020;11:191. 10.3389/fphar.2020.00191 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Hu W, Han Q, Zhao L, et al. Circular RNA circRNA_15698 aggravates the extracellular matrix of diabetic nephropathy mesangial cells via miR-185/TGF-β1. J Cell Physiol 2019;234:1469-76. 10.1002/jcp.26959 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Zeng O, Li F, Li Y, et al. Effect of Novel Gasotransmitter hydrogen sulfide on renal fibrosis and connexins expression in diabetic rats. Bioengineered 2016;7:314-20. 10.1080/21655979.2016.1197743 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Yang M, Wang B, Li M, et al. Connexin 43 is involved in aldosterone-induced podocyte injury. Cell Physiol Biochem 2014;34:1652-62. 10.1159/000366367 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Ji J, Zhao Y, Na C, et al. Connexin 43-autophagy loop in the podocyte injury of diabetic nephropathy. Int J Mol Med 2019;44:1781-8. 10.3892/ijmm.2019.4335 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Sun X, Huang K, Haiming X, et al. Connexin 43 prevents the progression of diabetic renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis by regulating the SIRT1-HIF-1α signaling pathway. Clin Sci (Lond) 2020;134:1573-92. 10.1042/CS20200171 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Li M, Ni WJ, Zhang MY, et al. MicroRNA-30/Cx43 axis contributes to podocyte injury by regulating ER stress in diabetic nephropathy. Ann Transl Med 2020;8:1674. 10.21037/atm-20-6989 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Kazlauskienė L, Butnorienė J, Norkus A. Metabolic syndrome related to cardiovascular events in a 10-year prospective study. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2015;7:102. 10.1186/s13098-015-0096-2 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Lipid and inflammatory cardiovascular risk worsens over 3 years in youth with type 2 diabetes: the TODAY clinical trial. Diabetes Care 2013;36:1758-64. 10.2337/dc12-2388 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. La Sala L, Prattichizzo F, Ceriello A. The link between diabetes and atherosclerosis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2019;26:15-24. 10.1177/2047487319878373 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Bergheanu SC, Bodde MC, Jukema JW. Pathophysiology and treatment of atherosclerosis: Current view and future perspective on lipoprotein modification treatment. Neth Heart J 2017;25:231-42. 10.1007/s12471-017-0959-2 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Lakshmanan S, Shekar C, Kinninger A, et al. Association of high-density lipoprotein levels with baseline coronary plaque volumes by coronary CTA in the EVAPORATE trial. Atherosclerosis 2020;305:34-41. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.05.014 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Zhang X, Jiang B, Luo G, et al. Hyperglycemia down-regulates apolipoprotein M expression in vivo and in vitro. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007;1771:879-82. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.04.020 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Luo G, Feng Y, Zhang J, et al. Rosiglitazone enhances apolipoprotein M (Apom) expression in rat's liver. Int J Med Sci 2014;11:1015-21. 10.7150/ijms.8330 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Richter S, Shih DQ, Pearson ER, et al. Regulation of apolipoprotein M gene expression by MODY3 gene hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha: haploinsufficiency is associated with reduced serum apolipoprotein M levels. Diabetes 2003;52:2989-95. 10.2337/diabetes.52.12.2989 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Cervin C, Axler O, Holmkvist J, et al. An investigation of serum concentration of apoM as a potential MODY3 marker using a novel ELISA. J Intern Med 2010;267:316-21. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02145.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Qi Y, Chen J, Lay A, et al. Loss of sphingosine kinase 1 predisposes to the onset of diabetes via promoting pancreatic β-cell death in diet-induced obese mice. FASEB J 2013;27:4294-304. 10.1096/fj.13-230052 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Wang J, Badeanlou L, Bielawski J, et al. Sphingosine kinase 1 regulates adipose proinflammatory responses and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2014;306:E756-68. 10.1152/ajpendo.00549.2013 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Wu X, Niu N, Brismar K, et al. Apolipoprotein M promoter polymorphisms alter promoter activity and confer the susceptibility to the development of type 1 diabetes. Clin Biochem 2009;42:17-21. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.10.008 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Liu D, Pan JM, Pei X, et al. Interaction Between Apolipoprotein M Gene Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms and Obesity and its Effect on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Susceptibility. Sci Rep 2020;10:7859. 10.1038/s41598-020-64467-6 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Zhou JW, Tsui SK, Ng MC, et al. Apolipoprotein M gene (APOM) polymorphism modifies metabolic and disease traits in type 2 diabetes. PLoS One 2011;6:e17324. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017324 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Yao S, Luo G, Liu H, et al. Apolipoprotein M promotes the anti-inflammatory effect of high-density lipoprotein by binding to scavenger receptor BI. Ann Transl Med 2020;8:1676 10.21037/atm-20-7008 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Kamble PG, Theorell-Haglöw J, Wiklund U, et al. Sleep apnea in men is associated with altered lipid metabolism, glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, and body fat percentage. Endocrine 2020;70:48-57. 10.1007/s12020-020-02369-3 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Ryan S. Adipose tissue inflammation by intermittent hypoxia: mechanistic link between obstructive sleep apnoea and metabolic dysfunction. J Physiol 2017;595:2423-30. 10.1113/JP273312 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Mazzotti DR, Keenan BT, Lim DC, et al. Symptom Subtypes of Obstructive Sleep Apnea Predict Incidence of Cardiovascular Outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019;200:493-506. 10.1164/rccm.201808-1509OC [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Wang H, Li X, Tang Z, et al. Cardiovascular Outcomes Post Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Ther 2020;11:1795-806. 10.1007/s13300-020-00870-6 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Karakaş MS, Altekin RE, Baktır AO, et al. Association between mean platelet volume and severity of disease in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome without risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars 2013;41:14-20. 10.5543/tkda.2013.42948 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Shi H, Xiang S, Huang X, et al. Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting the risk of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Transl Med 2020;8:1675. 10.21037/atm-20-6890 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- View on publisher site

- PDF (203.9 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 06 June 2022

The burden and risks of emerging complications of diabetes mellitus

- Dunya Tomic ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2471-2523 1 , 2 ,

- Jonathan E. Shaw ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6187-2203 1 , 2 na1 &

- Dianna J. Magliano ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9507-6096 1 , 2 na1

Nature Reviews Endocrinology volume 18 , pages 525–539 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

62k Accesses

356 Citations

55 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Diabetes complications

- Type 1 diabetes

- Type 2 diabetes

The traditional complications of diabetes mellitus are well known and continue to pose a considerable burden on millions of people living with diabetes mellitus. However, advances in the management of diabetes mellitus and, consequently, longer life expectancies, have resulted in the emergence of evidence of the existence of a different set of lesser-acknowledged diabetes mellitus complications. With declining mortality from vascular disease, which once accounted for more than 50% of deaths amongst people with diabetes mellitus, cancer and dementia now comprise the leading causes of death in people with diabetes mellitus in some countries or regions. Additionally, studies have demonstrated notable links between diabetes mellitus and a broad range of comorbidities, including cognitive decline, functional disability, affective disorders, obstructive sleep apnoea and liver disease, and have refined our understanding of the association between diabetes mellitus and infection. However, no published review currently synthesizes this evidence to provide an in-depth discussion of the burden and risks of these emerging complications. This Review summarizes information from systematic reviews and major cohort studies regarding emerging complications of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus to identify and quantify associations, highlight gaps and discrepancies in the evidence, and consider implications for the future management of diabetes mellitus.

With advances in the management of diabetes mellitus, evidence is emerging of an increased risk and burden of a different set of lesser-known complications of diabetes mellitus.

As mortality from vascular diseases has declined, cancer and dementia have become leading causes of death amongst people with diabetes mellitus.

Diabetes mellitus is associated with an increased risk of various cancers, especially gastrointestinal cancers and female-specific cancers.

Hospitalization and mortality from various infections, including COVID-19, pneumonia, foot and kidney infections, are increased in people with diabetes mellitus.

Cognitive and functional disability, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, obstructive sleep apnoea and depression are also common in people with diabetes mellitus.

As new complications of diabetes mellitus continue to emerge, the management of this disorder should be viewed holistically, and screening guidelines should consider conditions such as cancer, liver disease and depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Type 2 diabetes mellitus in older adults: clinical considerations and management

The cross-sectional and longitudinal relationship of diabetic retinopathy to cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Global, regional, and national burden and trend of diabetes in 195 countries and territories: an analysis from 1990 to 2025

Introduction.

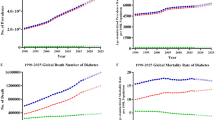

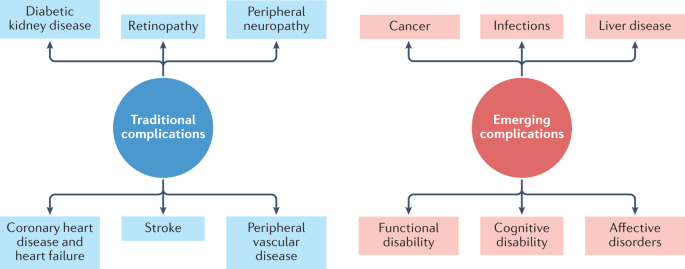

Diabetes mellitus is a common, albeit potentially devastating, medical condition that has increased in prevalence over the past few decades to constitute a major public health challenge of the twenty-first century 1 . Complications that have traditionally been associated with diabetes mellitus include macrovascular conditions, such as coronary heart disease, stroke and peripheral arterial disease, and microvascular conditions, including diabetic kidney disease, retinopathy and peripheral neuropathy 2 (Fig. 1 ). Heart failure is also a common initial manifestation of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) 3 and confers a high risk of mortality in those with T1DM or T2DM 4 . Although a great burden of disease associated with these traditional complications of diabetes mellitus still exists, rates of these conditions are declining with improvements in the management of diabetes mellitus 5 . Instead, as people with diabetes mellitus are living longer, they are becoming susceptible to a different set of complications 6 . Population-based studies 7 , 8 , 9 show that vascular disease no longer accounts for most deaths among people with diabetes mellitus, as was previously the case 10 . Cancer is now the leading cause of death in people with diabetes mellitus in some countries or regions (hereafter ‘countries/regions’) 9 , and the proportion of deaths due to dementia has risen since the turn of the century 11 . In England, traditional complications accounted for more than 50% of hospitalizations in people with diabetes mellitus in 2003, but for only 30% in 2018, highlighting the shift in the nature of complications of this disorder over this corresponding period 12 .

The traditional complications of diabetes mellitus include stroke, coronary heart disease and heart failure, peripheral neuropathy, retinopathy, diabetic kidney disease and peripheral vascular disease, as represented on the left-hand side of the diagram. With advances in the management of diabetes mellitus, associations between diabetes mellitus and cancer, infections, functional and cognitive disability, liver disease and affective disorders are instead emerging, as depicted in the right-hand side of the diagram. This is not an exhaustive list of complications associated with diabetes mellitus.

Cohort studies have reported associations of diabetes mellitus with various cancers, functional and cognitive disability, liver disease, affective disorders and sleep disturbance, and have provided new insights into infection-related complications of diabetes mellitus 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 . Although emerging complications have been briefly acknowledged in reviews of diabetes mellitus morbidity and mortality 11 , 17 , no comprehensive review currently specifically provides an analysis of the evidence for the association of these complications with diabetes mellitus. In this Review, we synthesize information published since the year 2000 on the risks and burden of emerging complications associated with T1DM and T2DM.

Diabetes mellitus and cancer

The burden of cancer mortality.

With the rates of cardiovascular mortality declining amongst people with diabetes mellitus, cancer deaths now constitute a larger proportion of deaths among this population in some countries/regions 8 , 9 . Although the proportion of deaths due to cancer appears to be stable, at around 16–20%, in the population with diabetes mellitus in the USA 7 , in England it increased from 22% to 28% between 2001 and 2018 (ref. 9 ), with a similar increase reported in Australia 8 . Notably, in England, cancer has overtaken vascular disease as the leading cause of death in people with diabetes mellitus and it is the leading contributor to excess mortality in those with diabetes mellitus compared with those without 9 . These findings are likely to be due to a substantial decline in the proportion of deaths from vascular diseases, from 44% to 24% between 2001 and 2018, which is thought to reflect the targeting of prevention measures in people with diabetes mellitus 18 . Over the same time period, cancer mortality rates fell by much less in the population with diabetes mellitus than in that without diabetes 9 , suggesting that clinical approaches for diabetes mellitus might focus too narrowly on vascular complications and might require revision 19 . In addition, several studies have reported that female patients with diabetes mellitus receive less-aggressive treatment for breast cancer compared with patients without diabetes mellitus, particularly with regard to chemotherapy 20 , 21 , 22 , suggesting that this treatment approach might result in increased cancer mortality rates in women with diabetes mellitus compared with those without diabetes mellitus. Although substantial investigation of cancer mortality in people with diabetes mellitus has been undertaken in high-income countries/regions, there is a paucity of evidence from low-income and middle-income countries/regions. It is important to understand the potential effect of diabetes mellitus on cancer mortality in these countries/regions owing to the reduced capacity of health-care systems in these countries/regions to cope with the combination of a rising prevalence of diabetes mellitus and rising cancer mortality rates in those with diabetes mellitus. One study in Mauritius showed a significantly increased risk of all-cause cancer mortality in patients with T2DM 23 , but this study has yet to be replicated in other low-income and middle-income countries/regions.

Gastrointestinal cancers

Of the reported associations between diabetes mellitus and cancer (Table 1 ), some of the strongest have been demonstrated for gastrointestinal cancers.

Hepatocellular carcinoma

In the case of hepatocellular carcinoma, the most rigorous systematic review on the topic — comprising 18 cohort studies with a combined total of more than 3.5 million individuals — reported a summary relative risk (SRR) of 2.01 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.61–2.51) for an association with diabetes mellitus 24 . This increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma with diabetes mellitus is supported by the results of another systematic review that included case–control studies 25 . Another review also found that diabetes mellitus independently increased the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in the setting of hepatitis C virus infection 26 .

Pancreatic cancer

The risk of pancreatic cancer appears to be approximately doubled in patients with T2DM compared with patients without T2DM. A meta-analysis of 36 studies found an adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 1.82 (95% CI 1.66–1.89) for pancreatic cancer among people with T2DM compared with patients without T2DM 27 (Table 1 ). However, it is possible that these findings are influenced by reverse causality — in this scenario, diabetes mellitus is triggered by undiagnosed pancreatic cancer 28 , with pancreatic cancer subsequently being clinically diagnosed only after the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Nevertheless, although the greatest risk (OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.87–2.25) of pancreatic cancer was seen in people diagnosed with T2DM 1–4 years previously compared with people without T2DM, those with a diagnosis of T2DM of more than 10 years remained at increased risk of pancreatic cancer (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.16–1.96) 27 , suggesting that reverse causality can explain only part of the association between T2DM and pancreatic cancer. Although T2DM accounts for ~90% of all cases of diabetes mellitus 29 , a study incorporating data from five nationwide diabetes registries also reported an increased risk of pancreatic cancer amongst both male patients (HR 1.53, 95% CI 1.30–1.79) and female patients (HR 1.25, 95% CI 1.02–1.53) with T1DM 30 .

Colorectal cancer

For colorectal cancer, three systematic reviews have shown a consistent 20–30% increased risk associated with diabetes mellitus 31 , 32 , 33 . One systematic review, which included more than eight million people across 30 cohort studies, reported an incidence SRR of 1.27 (95% CI 1.21–1.34) of colorectal cancer 31 , independent of sex and family history (Table 1 ). Similar increases in colorectal cancer incidence in patients with diabetes mellitus were reported in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies 32 and in a systematic review that included cross-sectional studies 33 .

Female-specific cancers

Endometrial, breast and ovarian cancers all occur more frequently in women with diabetes mellitus than in women without diabetes mellitus.

Endometrial cancer

For endometrial cancer, one systematic review of 29 cohort studies and a combined total of 5,302,259 women reported a SRR of 1.89 (95% CI 1.46–2.45) and summary incidence rate ratio (IRR) of 1.61 (95% CI 1.51–1.71) 34 (Table 1 ). Similar increased risks were found in two systematic reviews incorporating cross-sectional studies 35 , 36 , one of which found a particularly strong association of T1DM (relative risk (RR) 3.15, 95% CI 1.07–9.29) with endometrial cancer.

Breast cancer

The best evidence for a link between diabetes mellitus and breast cancer comes from a systematic review of six prospective cohort studies and more than 150,000 women, in which the hazard ratio (HR) for the incidence of breast cancer in women with diabetes mellitus compared with women without diabetes mellitus was 1.23 (95% CI 1.12–1.34) 32 (Table 1 ). Two further systematic reviews have also shown this increased association 37 , 38 .

The association of diabetes mellitus with breast cancer appears to vary according to menopausal status. In a meta-analysis of studies of premenopausal women with diabetes mellitus, no significant association with breast cancer was found 39 , whereas in 11 studies that included only postmenopausal women, the SRR was 1.15 (95% CI 1.07–1.24). The difference in breast cancer risk between premenopausal and postmenopausal women with diabetes mellitus was statistically significant. The increased risk of breast cancer after menopause in women with diabetes mellitus compared with women without diabetes mellitus might result from the elevated concentrations and increased bioavailability of oestrogen that are associated with adiposity 40 , which is a common comorbidity in those with T2DM; oestrogen synthesis occurs in adipose tissue in postmenopausal women, while it is primarily gonadal in premenopausal women 41 . Notably, however, there is evidence that hormone-receptor-negative breast cancers, which typically carry a poor prognosis, occur more frequently in women with breast cancer and diabetes mellitus than in women with breast cancer and no diabetes mellitus 42 , indicating that non-hormonal mechanisms also occur.

Ovarian cancer

Diabetes mellitus also appears to increase the risk of ovarian cancer, with consistent results from across four systematic reviews. A pooled RR of 1.32 (95% CI 1.14–1.52) was reported across 15 cohort studies and a total of more than 2.3 million women 43 (Table 1 ). A SRR of 1.19 (95% CI 1.06–1.34) was found across 14 cohort studies and 3,708,313 women 44 . Similar risks were reported in meta-analyses that included cross-sectional studies 45 , 46 .

Male-specific cancers: prostate cancer

An inverse association between diabetes mellitus and prostate cancer has been observed in a systematic review (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.86–0.96) 47 , and is probably due to reduced testosterone levels that occur secondary to the low levels of sex hormone-binding globulin that are commonly seen in men with T2DM and obesity 48 . Notably, however, the systematic review that showed the inverse association involved mostly white men (Table 1 ), whereas a systematic review of more than 1.7 million men from Taiwan, Japan, South Korea and India found that diabetes mellitus increased prostate cancer risk 49 , suggesting that ethnicity might be an effect modifier of the diabetes mellitus–prostate cancer relationship. The mechanisms behind this increased risk in men in regions of Asia such as Taiwan and Japan, where most study participants came from, remain unclear. Perhaps, as Asian men develop diabetes mellitus at lower levels of total adiposity than do white men 50 , the adiposity associated with diabetes mellitus in Asian men might have a lesser impact on sex hormone-binding globulin and testosterone than it does in white men. Despite the reported inverse association between diabetes mellitus and prostate cancer in white men, however, evidence suggests that prostate cancers that do develop in men with T2DM are typically more aggressive, conferring higher rates of disease-specific mortality than prostate cancers in men without diabetes mellitus 51 .

An assessment of cancer associations

As outlined above, a wealth of data has shown that diabetes mellitus is associated with an increased risk of various cancers. It has been argued, however, that some of these associations could be due to detection bias resulting from increased surveillance of people with diabetes mellitus in the immediate period after diagnosis 52 , or reverse causality, particularly in the case of pancreatic cancer 53 . However, neither phenomenon can account for the excess risks seen in the longer term. An Australian study exploring detection bias and reverse causality found that standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) for several cancer types in people with diabetes mellitus compared with the general population fell over time, but remained elevated beyond 2 years for pancreatic and liver cancers 54 , suggesting that diabetes mellitus is a genuine risk factor for these cancer types.

A limitation of the evidence that surrounds diabetes mellitus and cancer risk is high clinical and methodological heterogeneity across several of the large systematic reviews, which makes it difficult to be certain of the effect size in different demographic groups. Additionally, many of the studies exploring a potential association between diabetes mellitus and cancer were unable to adjust for BMI, which is a major confounder. However, a modelling study that accounted for BMI found that although 2.1% of cancers worldwide in 2012 were attributable to diabetes mellitus as an independent risk factor, twice as many cancers were attributable to high BMI 55 , so it is likely that effect sizes for cancer risk associated with diabetes mellitus would be attenuated after adjustment for BMI. Notably, however, low-income and middle-income countries/regions had the largest increase in the numbers of cases of cancer attributable to diabetes mellitus both alone and in combination with BMI 55 , highlighting the need for public health intervention, given that these countries/regions are less equipped than high-income countries/regions to manage a growing burden of cancer.

As well as the cancer types outlined above, diabetes mellitus has also been linked to various other types of cancer, including kidney cancer 56 , bladder cancer 57 and haematological malignancies; however, the evidence for these associations is not as strong as for the cancers discussed above 58 . Diabetes mellitus might also be associated with other cancer types such as small intestine cancer, but the rarity of some of these types makes it difficult to obtain sufficient statistical power in analyses of any potential association.

Potential aetiological mechanisms