The Whatfix Blog | Drive Digital Adoption

- CIO CIO CIO Blog Explore all new CIO, change, and ITSM content on our enterprise digitalization blog hub. Explore by Category Change Management Digital Transformation ITSM

- Employee Experience Employee Experience EX Blog Explore all new employee experience related content on our EX blog hub. Explore by category Employee Training HR & People Ops Sales Ops

- CX & Product Product CX & Product Ops Blog Explore all new CX and product-related content on our CX and product manager hub. Explore by category Product Ops Support User Onboarding

- Resources Customer Experience What Is a Digital Adoption Platform? Learn how DAPs enable technology users in our ultimate guide. Resources Case Studies eBooks Podcasts White Papers

- Explore Whatfix What Is Whatfix? Whatfix DAP Create contextual in-app guidance in the flow of work with Whatfix DAP. Mirror Easily create simulated application experiences for hands-on IT training with Whatfix Mirror. Product Analytics Analyze how users engage with desktop and web apps with no-code event tracking. Resources About Us Pricing Userization Whatfix AI

- Digital Transformation

8 Examples of Innovative Digital Transformation Case Studies (2024)

- Published: January 19, 2022

- Updated: October 3, 2024

With the rapid pace of technological advancement, every organization needs to undergo digital transformation and, most likely, transform multiple times to stay relevant and competitive.

However, before you can reap the benefits of new technology, you must first get your customers and employees to adapt to this change successfully—and here lies a significant digital transformation challenge.

Organizations thriving in this digital-first era have developed digital innovation strategies prioritizing the change management mindset. This paradigm shift implies that organizations should continuously explore improving business processes .

8 Best Examples of Digital Transformation Case Studies in 2024

- Amazon Business

- Under Armour

- Internet Brands®

- Michelin Solutions

8 Examples of Inspiring Digital Transformation Case Studies

While digital transformation presents unique opportunities for organizations to innovate and grow, it also presents significant digital transformation challenges . Also, digital maturity and levels of digital transformation by sector vary widely.

If you have the budget, you can consider hiring a digital transformation consulting company to help you plan your digitization. However, the best way to develop an effective digital transformation strategy is to learn by example.

Here are the 8 inspiring digital transformation case studies to consider when undertaking transformation projects in 2024:

1. Amazon extended the B2C model to embrace B2B transactions with a vision to improve the customer experience.

Overview of the digital transformation initiative

Amazon Business is an example of how a consumer giant transitions to the B2B space to keep up with the digital customer expectations. It provides a marketplace for businesses to purchase from Amazon and third parties. Individuals can also make purchases on behalf of their organizations and integrate order approval workflows and reporting.

The approach

- Amazon created a holistic marketplace for B2B vendors by offering over 250 million products ranging from cleaning supplies to industrial equipment.

- It introduced free two-day shipping on orders worth $49 or more and exclusive price discounts. It further offered purchase system integration, tax-exemption on purchases from select qualified customers, shared payment methods, order approval workflows, and enhanced order reporting.

- Amazon allowed manufacturers to connect with buyers & answer questions about products in a live expert program.

- Amazon could tap the B2B wholesale market valued between $7.2 and $8.2 trillion in the U.S. alone.

- It began earning revenue by charging sales commissions ranging from 6-15% from third-party sellers, depending on the product category and the order size.

- It could offer more personalized products for an improved customer experience.

2. Netflix transformed the entertainment industry by offering on-demand subscription-based video services to its customers.

Like the video rental company Blockbuster, Netflix also had a pay-per-rental model, which included DVD sales and rent-by-mail services. However, Netflix anticipated a change in customer demand with rising digitalization and provided online entertainment, thereby wiping out Blockbuster – and the movie rental industry – entirely.

- In 2007, Netflix launched a video-on-demand streaming service to supplement their DVD rental service without any additional cost to their subscriber base.

- It implemented a simple and scalable business model and infused 10% of its budget in R&D consistently.

- The company has an unparalleled recommendation engine to provide a personalized and relevant customer experience.

- Netflix is the most popular digital video content provider, leading other streaming giants such as Amazon, Hulu, and Youtube with over 85% market share.

- Netflix added a record 36 million subscribers directly after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Tesla uses connected car technology and over-the-air software updates to enhance customer experience, enable cost savings, and reduce carbon emissions.

No digital transformation discussion is complete without acknowledging the unconventional ideas implemented by Elon Musk. Tesla was a huge manifestation of digital transformation as the core motive was to prove that electric cars are better than their gasoline counterparts both in looks and performance.

Over the years, Tesla has innovated continuously to improve its product, make itself more economical, and reduce its carbon footprint.

- Tesla is the only auto manufacturer globally, providing automatic over-the-air firmware updates that allow its cars to remotely improve their safety, performance, and infotainment capabilities. For example, the OTA update could fix Tesla’soverheating issues due to power fluctuation.

- Tesla launched an autopilot feature to control the speed and position of the car when on highways to avoid potential accidents. However, the user still has to hold the wheel; the vehicle controls everything else. This connected car technology has created an intelligent data platform and smart autonomous driving experience.

- Tesla further ventured into a data-driven future, and it uses analytics to obtain actionable insights from demand trends and common complaints. A noteworthy fact is that the company has been collecting driving data from all of its first and second-generation vehicles. So far, Tesla has collected driving data on 8 billion miles while Google’s autonomous car project, Waymo , has accumulated data on 10 million miles.

- Tesla’s over-the-air updates reduce carbon emissions by saving users’ dealer visits. Additionally, these updates save consumers time and money.

- Tesla delivered a record 936,172 vehicles in 2021, an 87 % increase over the 499,550 vehicle deliveries made in 2020.

4. Glassdoor revolutionized the recruitment industry by allowing employees to make informed decisions.

Glassdoor is responsible for increasing transparency in the workplace and helping people find the right job by allowing them to see millions of peer-to-peer reviews on employers, including overall company culture, their CEOs, benefits, salaries, and more.

- Glassdoor gathers and analyzes employee reviews on employers to provide accurate job recommendations to candidates and vice-versa. It also allows recruitment agencies and organizations to download valuable data points for in-depth analysis & reporting.

- It further introduced enhanced profiles as a paid program, allowing companies to customize their content on the Glassdoor profiles, including job listings, “Why is it the Best Place to Work” tabs, social media properties, and more. This gives companies a new, innovative way to attract and recruit top talent.

- Glassdoor created the largest pool of interview questions, salary insights, CEO ratings, and organizational culture via a peer-to-peer network, making it one of the most trustworthy, extensive jobs search and recruiting platforms – and one of the most well-recognized review sites

- Glassdoor leverages its collected data for labor market research in the US. Its portfolio of Fortune’s “Best Companies to Work For” companies outperformed the S&P 500 by 84.2%, while the “Best Places to Work” portfolio outperformed the overall market by 115.6%.

5. Under Armour diversified from an athletic apparel company to a new data-driven digital business stream to transform the fitness industry.

Under Armour introduced the concept of “Connected Fitness” by providing a platform to track, analyze and share personal health data directly to its customers’ phones.

- Under Armour acquired several technology-based fitness organizations such as MapMyFitness, MyFitnessPal, and European fitness app Endomondo for a combined $715 million to obtain the required technology and an extensive customer database to get its fitness app up and running. The application provides a stream of information to Under Armour, identifying fitness and health trends. For example, Under Armour (Baltimore) immediately recognized a walking trend that started in Australia, allowing them to deploy localized marketing and distribution efforts way before their competitors knew about it.

- Under Armour merged its physical and digital offerings to provide an immersive customer experience via products such as Armourbox. The company urged its customers to go online and share their training schedule, favorite shoe style, and fitness goals. It used advanced analytics to send customers new shoes or apparel on a subscription basis, offering customers a more significant value over their lifetime.

- It additionally moved to an agile development model and data center footprint with the ERP SAP HANA .

- Under Armour additionally leveraged Dell EMC’s Data Protection and Dell Technologies to help fuel digital innovation and find peak value from its data.

- Under Armour created a digital brand with a strong consumer focus, agility, and change culture.

- With the Connected Fitness app, it provided a customer experience tailored to each consumer.

6. Internet Brands® subsidiary Baystone Media leverages Whatfix DAP to drive product adoption of its healthcare businesses.

Baystone Media provides end-to-end marketing solutions for healthcare companies by providing a low-cost, high-value subscription offering of Internet Brands® to promote their practices digitally. Baystone Media empowers its customers by offering a codeless creation of personalized websites. However, as its userbase is less tech-savvy, customers were unable to make the most of their solution.

The idea was to implement a solution for Baystone Media & its sister companies to enable its clients to navigate its platforms easily. In addition to PDFs and specific training videos, the search was on for a real-time interactive walkthrough solution, culminating with Whatfix .

Baystone media saw a 10% decrease in inbound calls and a 4.17% decrease in support tickets, giving them the runway to spend more time enhancing its service for the clients.

7. Sophos implemented Salesforce to streamline its business and manage customer relations more effectively.

Sophos went live with Salesforce to accelerate its sales process , enhance sales productivity , and increase the number of accounts won. However, the complex interface and regular updates of Salesforce resulted in a decreased ROI.

- Sophos implemented Whatfix to provide interactive, on-demand training that helped users learn in the flow of work. The 24*7 availability of on-demand self-support, contextual guidance, and smart tips allowed Sophos to manage its new CRM implementation effectively.

- It unified internal communications using Whatfix content. First, they created walkthroughs for the basic functionality of Salesforce such as lead management, opportunities, etc. Next, they moved to slightly more complex features that their users were uncomfortable with and created guided walkthroughs and smart pop-ups. Sophos also used Whatfix to align the sales and product management teams by embedding videos and other media to unify product communication instead of relying on various communication tools.

- Sophos experienced a reduction in sales operations support tickets globally by 15% (~12,000 tickets). It saved 1070 man-hours and achieved an ROI of 342%.

8. Michelin Solutions uses IoT & AI to provide customers with a more holistic mobility experience.

The digital strategy of Michelin Solutions has essentially centered around three priorities:

- Creating a personalized relationship with customers and end-users

- Developing new business models

- Improving their existing business processes

- AI is extensively used in R&D, enabling the digital supply chain driven through digital manufacturing and predictive maintenance. For example, connected bracelets assist machine operators with the manufacturing process.

- It deployed sophisticated robots to take over the clerical tasks and leveraged advanced analytics to become a data-driven organization.

- Offerings such as Effifuel & Effitires resulted in significant cost savings and improved overall vehicle efficiency.

- Michelin Solutions carefully enforced cultural change and launched small pilots before the change implementation .

- Effifuel led to extra savings for organizations and doubled per-vehicle profits.

- A reduction in fuel consumption by 2.5 L per 100km was observed which translates into annual savings of €3,200 for long-haul transport (at least 2.1% reduction in the total cost of ownership & 8 tonnes in CO2 emissions).

- Michelin Solutions shifted its business model from selling tires to a service guaranteeing performance, helping it achieve higher customer satisfaction, increased loyalty, and raised EBITDA margins.

Each industry & organization faces unique challenges while driving digital transformation initiatives. Each organization must find a personalized solution and the right digital transformation model when implementing new technology. Their challenges can prepare you better for the potential roadblocks, but the specific solutions will need to be personalized according to your business requirements.

Open communication with your customers and employees will help you spot potential issues early on, and you can use case studies like these as a starting point.

If you would like to learn how you can achieve these results by using a digital adoption platform , then schedule a conversation with our experts today.

Request a demo to see how Whatfix empowers organizations to improve end-user adoption and provide on-demand customer support

- Digital Marketing

- Facebook Marketing

- Instagram Marketing

- Ecommerce Marketing

- Content Marketing

- Data Science Certification

- Machine Learning

- Artificial Intelligence

- Data Analytics

- Graphic Design

- Adobe Illustrator

- Web Designing

- UX UI Design

- Interior Design

- Front End Development

- Back End Development Courses

- Business Analytics

- Entrepreneurship

- Supply Chain

- Financial Modeling

- Corporate Finance

- Project Finance

- Harvard University

- Stanford University

- Yale University

- Princeton University

- Duke University

- UC Berkeley

- Harvard University Executive Programs

- MIT Executive Programs

- Stanford University Executive Programs

- Oxford University Executive Programs

- Cambridge University Executive Programs

- Yale University Executive Programs

- Kellog Executive Programs

- CMU Executive Programs

- 45000+ Free Courses

- Free Certification Courses

- Free DigitalDefynd Certificate

- Free Harvard University Courses

- Free MIT Courses

- Free Excel Courses

- Free Google Courses

- Free Finance Courses

- Free Coding Courses

- Free Digital Marketing Courses

25 Digital Transformation Case Studies [2024]

In a world where technology relentlessly reshapes our world, businesses that fail to adapt are destined for obsolescence. These 15 digital transformation case studies present a thrilling narrative of change, charting the journeys of companies that dared to embrace the digital frontier. Each story unfolds as a high-stakes gamble where traditional practices are disrupted, often under the threat of imminent collapse. These businesses, spanning diverse industries from retail to agriculture, engaged in transformative practices not just to survive but to radically reinvent themselves. As we explore these narratives, consider them as a playbook for disruption, illustrating the necessity of digital evolution and its perils and promises.

25 Digital Transformation Case Studies

1. nordstrom: reinventing retail through digital customer experiences.

Nordstrom, an upscale American chain of department stores, has long been known for its commitment to customer service. As digital technologies evolved, Nordstrom embraced a digital transformation strategy to enhance its customer experience and seamlessly integrate online and in-store shopping.

Transformation

a. Omni-channel Integration: Nordstrom invested heavily in creating a seamless omni-channel experience. They enhanced their capabilities to monitor inventory in real-time both in stores and online, enabling customers to verify product availability and reserve items for in-store pickup.

b. Mobile App Enhancements: The Nordstrom mobile app was enhanced with features like “Style Boards,” a digital tool allowing salespeople to create and share personalized fashion recommendations virtually.

c. Data Analytics: Using advanced data analytics, Nordstrom acquired deep insights into customer preferences and shopping behaviors. This enabled them to tailor their marketing efforts and enhance customer engagement effectively.

The digital initiatives paid off by enhancing customer engagement and satisfaction. The ability to shop seamlessly between online and physical stores improved the overall shopping experience, increasing sales and customer loyalty.

Related: Evolution of Digital Transformation

2. Mayo Clinic: Digital Innovation in Healthcare

The Mayo Clinic is recognized worldwide for its specialized medical care. Faced with the growing need for healthcare modernization and improved patient outcomes, Mayo Clinic initiated a comprehensive digital transformation.

a. Telemedicine: Adopting telemedicine technologies was accelerated, allowing patients to consult with Mayo Clinic specialists remotely. This was specifically crucial during pandemic scenarios

b. Electronic Health Records (EHR): Mayo Clinic implemented a state-of-the-art EHR system to streamline patient information management across all points of care, improving coordination and treatment outcomes.

c. AI and Machine Learning: They embraced AI technologies for diagnostic imaging, predictive analytics, and personalized medicine, aiming to enhance diagnosis accuracy and patient care planning.

The digital transformation at Mayo Clinic has significantly enhanced patient accessibility, care coordination, and efficiency. Telemedicine has expanded its reach, particularly to those unable to travel for medical care, and AI integration has improved diagnostic and treatment precision.

3. Ford Motor Company: Embracing Digital Manufacturing and Connected Cars

Ford, a century-old automotive manufacturer, faced increasing competition from traditional car manufacturers and new tech-driven entrants like Tesla. In response, Ford launched an aggressive digital transformation strategy to revamp its manufacturing processes and product offerings.

a. Smart Factories: Ford introduced advanced manufacturing techniques in its factories, employing robotics, AI, and IoT to enhance production efficiency and flexibility. Using connected sensors and predictive analytics helped minimize downtime and optimize maintenance.

b. Connected Cars: Ford increased its investment in developing connected car technologies, which enable vehicles to communicate with one another and with infrastructure, enhancing safety and driving experiences. Features include remote services, real-time traffic updates, and emergency response systems.

c. Electric Vehicles (EV) Innovation: To align with global sustainability trends, Ford accelerated its development of electric vehicles, supported by a digital ecosystem that offers an integrated network of charging stations and a smart, user-friendly interface for managing vehicle charging.

Ford’s digital transformation has improved its manufacturing efficiency and positioned it as a leader in the future mobility space, with advancements in connected cars and a strong focus on electric vehicles. These efforts have helped Ford stay competitive in a rapidly evolving automotive landscape.

4. Singapore’s Public Utilities Board (PUB): Digital Water Management

Singapore’s Public Utilities Board (PUB) is responsible for the collection, development, distribution, and reclamation of water in Singapore, a nation with limited natural resources. The Public Utilities Board (PUB) initiated a digital transformation project aimed at boosting sustainability and efficiency in water management.

a. Smart Water Metering: Implementing smart meters across the city-state enabled real-time water usage monitoring, helping to detect leaks early and educate consumers about their water consumption patterns.

b. Automated Water Quality Monitoring: PUB deployed sensors throughout the water supply network to continuously monitor water quality and operational parameters, utilizing AI to predict and address potential issues before they impact consumers.

c. Virtual Singapore: PUB participated in the ‘Virtual Singapore’ project, which features a dynamic three-dimensional city model and a collaborative data platform incorporating hydrological models to simulate water movements and accumulation. This contribution enhances flood management and urban planning.

These technological advancements have made Singapore’s water management system one of the most efficient and sustainable in the world. The integration of digital tools has enabled PUB to ensure a continuous, safe water supply and effective management of the nation’s water resources, even as demand grows and climate challenges intensify.

Related: Impact of Digital Transformation in Manufacturing Sector

5. Netflix: Pioneering the Streaming Revolution

Netflix started as a DVD rental service by mail but transformed into a global streaming giant. As consumer preferences shifted from physical rentals to digital streaming, Netflix pivoted its business model to focus on online content delivery and original programming.

a. Streaming Technology: Netflix invested heavily in developing robust streaming technology, capable of delivering high-quality video content over the internet. This technology adjusts to the user’s bandwidth, ensuring an uninterrupted viewing experience.

b. Data Analytics and Machine Learning: Utilizing big data analytics and machine learning, Netflix analyzes vast amounts of data on viewer preferences to recommend personalized content and to decide which new series and films to produce.

c. Original Content: Transitioning from licensing to producing original content, Netflix created a wide array of popular shows and movies, becoming a major player in the entertainment industry, with its productions receiving critical acclaim and awards.

Netflix’s focus on technology and data-driven content creation has changed how people consume entertainment and how it’s produced. It has grown into one of the most significant entertainment platforms globally, with a vast subscriber base that enjoys content across many genres and languages.

6. DBS Bank: Leading Digital Banking in Asia

DBS Bank, the biggest bank in Southeast Asia, faced intense competition from traditional banks and new fintech startups. In response, DBS embarked on a comprehensive digital transformation journey to redefine banking in a digital world.

a. Digital-Only Banking: DBS launched Digibank, a mobile-only bank in India and Indonesia, which offers a paperless, signatureless, and branchless banking experience. This initiative aimed to tap into the mobile-savvy population in these countries.

b. API Platform: DBS was one of the first banks in Asia to create a comprehensive banking API platform, allowing businesses to integrate banking services into their applications seamlessly, enhancing customer experiences, and creating new revenue streams.

c. Data-Driven Insights: Leveraging big data, DBS provides personalized financial advice to customers. They use AI to offer tailored investment and savings solutions based on individual spending habits and financial goals.

DBS’s digital initiatives have set a new standard in the banking industry, significantly improving customer satisfaction and operational efficiencies. Their digital-first approach has attracted millions of new customers, particularly among the tech-savvy younger demographic, and has solidified their position as a leader in the digital banking space.

7. Domino’s Pizza: From Pizza Company to Tech Company

Domino’s Pizza recognized the importance of technology in the fast-food industry early and embarked on an ambitious digital transformation to become more than just a pizza company. They aimed to enhance customer experience, streamline operations, and increase sales through digital channels.

a. Online Ordering System: Domino’s developed an innovative digital ordering system with a website, mobile app, and voice-recognition system. This system made ordering pizzas quick and easy for customers.

b. Pizza Tracker: Domino’s introduced the “Pizza Tracker,” a feature that enables customers to follow their orders in real-time from preparation through delivery, thereby increasing transparency and boosting customer engagement.

c. AI and Automation: To reduce delivery times and costs, Domino’s has experimented with artificial intelligence and automation technologies, including chatbots for ordering and robotic units for pizza delivery.

These digital initiatives have transformed Domino’s into a tech-forward company, significantly boosting online sales. They have also improved operational efficiencies and customer satisfaction, keeping Domino’s competitive in a fiercely contested market.

Related: Pros and Cons of Digital Transformation

8. Delta Airlines: Enhancing Travel Experience with Digital Solutions

Delta Airlines, one of the largest airlines worldwide, has consistently sought to leverage technology to better its operational efficacy and customer service. Recognizing the evolving needs of modern travelers, Delta has invested in digital technologies to enhance the passenger experience.

a. Mobile App Innovations: Delta’s mobile app includes features like check-in, boarding pass access, flight tracking, and notifications about gate changes or delays, making travel more manageable and less stressful for passengers.

b. RFID Baggage Tracking: Delta implemented Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology for baggage handling. This tech upgrade provides customers with real-time updates on their checked luggage and significantly reduces the rate of lost or misdirected bags.

c. Biometrics for Seamless Travel: Delta has introduced biometric boarding at several airports, using facial recognition technology to speed up the boarding process while enhancing security.

Delta’s digital transformation efforts have improved customer satisfaction by making flying more pleasant less stressful and enhancing operational efficiencies. The use of advanced technology has solidified Delta’s reputation as an innovator in the airline industry.

9. Nike: Revolutionizing Retail with Digital Engagement

Nike, a leading sports apparel and equipment manufacturer, faced the challenge of staying relevant in a rapidly changing retail landscape dominated by digital engagement and e-commerce. Nike embarked on an aggressive digital transformation strategy to maintain its market leadership and connect with a global audience.

a. Nike+ Ecosystem: Nike developed the Nike+ ecosystem, which includes apps for fitness tracking, coaching, and community engagement. These apps collect data that Nike uses to improve customer engagement, tailor marketing efforts, and enhance product development.

b. Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) Sales: Nike boosted its direct-to-consumer channel through its website and mobile app, enhancing the customer shopping experience with personalized recommendations based on user activity and preferences.

c. Augmented Reality: Nike introduced augmented reality features in its app, allowing customers to try on shoes virtually, ensuring a better fit and reducing return rates.

Nike’s focus on digital has dramatically shifted its sales strategy, significantly increasing its direct-to-consumer revenue. The personalized and connected experiences have fostered brand loyalty and enabled Nike to gather valuable customer data to drive future product and marketing strategies.

10. Southern California Edison: Powering Up Grid Modernization

Southern California Edison (SCE), one of the biggest electric utilities in the U.S., needed to address aging infrastructure, regulatory pressures, and increasing demand for renewable energy sources. SCE launched a digital transformation initiative to modernize its electrical grid to improve reliability, efficiency, and sustainability.

a. Smart Grid Technology: SCE implemented a smart grid with advanced metering infrastructure, digital sensors, and automated controls throughout the network. This technology provides SCE with real-time data to manage energy flow and respond to issues efficiently.

b. Renewable Integration: The utility company enhanced its grid to handle more renewable energy sources. Digital tools help manage the variability and intermittency of renewables like solar and wind.

c. Customer Engagement Platforms: SCE developed online tools and mobile applications that give customers detailed insights into their energy usage, helping them manage consumption and reduce costs.

SCE’s digital initiatives have enhanced grid reliability and efficiency, which is crucial for incorporating renewable energy. These initiatives have enabled consumers to take a more active role in managing their energy consumption, supporting broader sustainability objectives and compliance with regulatory standards.

Related: Use of Digital Transformation in Real Estate

11. L’Oréal: Digital Beauty Transformation

L’Oréal, the world’s largest cosmetics company, recognized the need to digitally transform to maintain its leadership and respond to changing consumer behaviors, particularly the rise of e-commerce and digital-first beauty brands.

a. Virtual Try-On Technology: L’Oréal acquired the augmented reality and artificial intelligence company ModiFace, which offered customers virtual try-on features for makeup and hair color, enhancing the online shopping experience.

b. Personalized Marketing: Using AI-driven analytics, L’Oréal was able to offer personalized product recommendations and targeted marketing campaigns, improving customer engagement and satisfaction.

c. E-commerce and Social Selling: L’Oréal expanded its e-commerce presence and integrated social media selling platforms, enabling customers to purchase products directly through social media ads and influencers, tapping into the social commerce trend.

These digital initiatives have improved L’Oréal’s engagement with tech-savvy consumers and boosted online sales significantly. The company has stayed competitive in a rapidly evolving beauty market, ensuring that digital and physical retail strategies complement each other.

12. The New York Times: Navigating the Shift to Digital Journalism

As the media landscape shifted from print to digital, The New York Times faced the challenge of adapting to changing reader habits and the decline of traditional newspaper revenue from ads and subscriptions.

a. Digital Subscription Model: The NYT introduced a digital subscription model, which has become a significant revenue stream. It allows them to cater to global readers online, surpassing the limitations of print distribution.

b. Enhanced Digital Content: The publication expanded its digital offerings, including podcasts, video content, and interactive journalism, providing a more comprehensive media experience that appeals to a broader audience.

c. Data Analytics: Using data analytics, The NYT can understand reader preferences and engagement, tailoring content and marketing strategies to increase subscriber retention and attract new readers.

The shift to a digital-first approach has rejuvenated The New York Times, turning it into a model for successful and effective digital transformation in the media industry. It has stabilized its revenue and expanded its audience globally, showcasing its adaptability and innovation in journalism.

13. DHL: Logistics and Supply Chain Innovation

DHL, a global leader in logistics, faced the challenge of adapting to the rapidly evolving demands of e-commerce and global trade. DHL embarked on a digital transformation journey to streamline operations and improve customer service to maintain its competitive edge.

a. Internet of Things (IoT) and Robotics: DHL invested in IoT technologies to enhance tracking and monitoring of shipments. Robotics solutions were integrated into warehouses to automate sorting and packaging processes, reducing errors and improving efficiency.

b. Predictive Analytics: By implementing predictive analytics, DHL improved its logistics planning capabilities. This technology helps anticipate delays and optimize routes in real-time, significantly reducing delivery times.

c. Customer Interaction Platforms: DHL upgraded its customer service platforms, introducing chatbots and AI-driven support systems to provide quick and reliable customer service around the clock.

These innovations have improved operational efficiencies and enhanced client satisfaction by providing more accurate and timely delivery services. DHL’s adoption of advanced technologies has solidified its position as a leader in the logistics sector, capable of handling the complexities of modern supply chains.

Related: Predictions About the Future of Digital Transformation

14. U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA): Enhancing Public Services Through Digital Outreach

The U.S. Social Security Administration, which provides financial support to millions of Americans, faced challenges in service accessibility and administrative efficiency. The SSA initiated a digital transformation strategy to address these issues and better serve the public.

a. Online Services Expansion: The SSA expanded its online platform to allow users to apply for benefits, manage their accounts, and access services without visiting a physical office. This was particularly vital during the COVID-19 pandemic.

b. Digital Documentation: The transition to digital documentation systems helped reduce paperwork, streamline processes, and increase the speed and accuracy of processing claims and applications.

c. Data Security Enhancements: With increased digital interactions, the SSA invested heavily in cybersecurity measures to protect sensitive personal information and prevent fraud.

The SSA’s digital transformation has significantly improved accessibility to services, allowing beneficiaries to manage their benefits easily and securely from home. These changes have also improved the agency’s efficiency and reduced operational costs, ensuring sustainability and responsiveness to public needs.

15. John Deere: Digital Agriculture and Smart Farming Solutions

John Deere, a leading agricultural machinery manufacturer, identified the potential of digital technologies to revolutionize farming. John Deere embarked on a digital transformation journey to maintain its leadership in the industry and help farmers increase productivity and sustainability.

a. Precision Agriculture: John Deere developed advanced precision agriculture technologies, integrating GPS and IoT sensors into their equipment. These technologies empower farmers to continuously monitor crop health, soil conditions, and weather patterns in real-time, enhancing the efficiency of planting, watering, and harvesting activities.

b. Data Analytics Platforms: The company introduced platforms that analyze data collected from farm equipment to provide actionable insights, aiding farmers make informed decisions about crop management and resource allocation.

c. Autonomous Machines: John Deere invested in developing autonomous tractors and combined harvesters. These machines can operate with minimal human oversight, increasing efficiency and reducing the labor needed for various farming operations.

John Deere’s digital innovations have profoundly impacted the agricultural sector. Farmers using these advanced tools can achieve higher crop yields, reduce waste, and minimize environmental impact. The company’s commitment to integrating digital technologies into its products has solidified its position as a leader in the agricultural machinery industry, ensuring that it continues to match the evolving requirements of modern agriculture.

16. IKEA: Enhancing the Furniture Shopping Experience with Digital Tools

IKEA, known for its flat-pack furniture and home accessories, aimed to bridge the gap between online and in-store shopping to enhance customer experience and streamline operations.

a. Virtual Reality Showrooms: IKEA implemented virtual reality tools that allow customers to see how furniture would appear in their homes before buying, which has improved customer satisfaction and reduced return rates.

b. Online Planning Tools: They developed online tools for room planning and furniture customization, helping customers design their living spaces and make informed decisions remotely.

c. Supply Chain Optimization: Utilizing AI and machine learning, IKEA optimized its supply chain processes, reducing costs and improving delivery times with better inventory management and distribution strategies.

These digital strategies have markedly boosted IKEA’s online sales and enhanced customer engagement. By providing immersive and interactive digital tools, IKEA has improved the shopping experience, leading to greater customer loyalty and market competitiveness.

Related: Digital Transformation Statistics

17. HSBC: Digital Transformation in Global Banking

HSBC, one of the world’s largest banking and financial services organizations, faced the challenge of modernizing its services to meet the expectations of a digitally savvy customer base and to compete with emerging fintech companies.

a. Global Banking App: HSBC launched a new mobile banking app providing a comprehensive range of services, including foreign currency exchange, global transfers, and real-time account management.

b. Blockchain for Trade Finance: They adopted blockchain technology to streamline and secure international trade finance processes, significantly reducing the time and cost of transactions.

c. AI-Driven Fraud Detection: Implementing cutting-edge AI algorithms, HSBC enhanced its security measures by predicting and preventing fraudulent transactions in real-time.

HSBC’s digital transformation has led to a more agile and secure banking experience, attracting a younger demographic and enhancing global customer satisfaction. Integrating advanced technologies has also positioned HSBC as a leader in digital innovation within the banking sector.

18. Adobe: Transforming Creative Industries with Cloud-Based Solutions

Adobe, a leader in creative software, recognized the need to transition from traditional desktop applications to a more flexible, cloud-based model to cater to the evolving demands of creative professionals globally.

a. Adobe Creative Cloud: Adobe shifted its suite of creative tools, such as Photoshop and Illustrator, to a subscription-based service, Adobe Creative Cloud. This shift allowed users to access their tools and files from any device and facilitated real-time collaboration.

b. AI and Machine Learning Enhancements: Incorporating AI technologies like Adobe Sensei, Adobe enhanced features across its products to improve user experience, offering capabilities such as automated image editing and smart design suggestions.

c. Education and Community Building: Adobe expanded its training resources and community features, providing extensive tutorials, live sessions, and a platform for creatives to share work and insights, fostering a collaborative environment.

Adobe’s shift to the cloud has revolutionized how creative content is produced, shared, and monetized, significantly enhancing productivity and creativity among professionals. This transformation has solidified Adobe’s leadership in the digital creative market, broadening its user base and increasing customer engagement.

19. Walmart: Revolutionizing Retail with Omnichannel Strategies

Walmart, the world’s largest retailer, aimed to integrate its vast network of physical stores with digital technologies to provide a seamless shopping experience and compete with e-commerce giants like Amazon.

a. Enhanced E-commerce Platform: Walmart upgraded its online platform to facilitate an efficient, user-friendly shopping experience, featuring a robust mobile app that integrates with in-store services.

b. Advanced Inventory Management: Utilizing IoT and AI, Walmart implemented advanced inventory systems to optimize stock levels and logistics, ensuring product availability and rapid fulfillment.

c. Pickup and Delivery Services: They expanded their pickup and delivery options, allowing customers to order online and choose convenient, flexible methods for receiving their purchases, including curbside pickup and same-day delivery.

Walmart’s digital transformation has significantly enhanced customer convenience, driving increased online and in-store sales. By leveraging technology to bridge the gap amidst physical and digital retail, Walmart has strengthened its market position and customer loyalty, setting a new standard in the retail sector.

Related: Digital Transformation in Telecom Case Studies

20. Siemens: Advancing Industrial Automation with Digital Twin Technology

Siemens, a global powerhouse in electrical engineering and electronics, recognized the need to innovate in industrial automation to maintain its leadership in the market. They aimed to leverage digital technologies to enhance manufacturing processes and product development.

a. Digital Twin Implementation: Siemens implemented digital twin technology, which generates virtual models of physical systems to simulate, forecast, and enhance the performance of machines and processes before their actual deployment.

b. IoT and Edge Computing: They integrated IoT with edge computing in their manufacturing operations to gather and analyze data at the source, improving real-time decision-making and operational efficiency.

c. Customizable Automation Solutions: Siemens developed a range of customizable automation solutions tailored to the particular needs of industries, facilitating greater flexibility and efficiency in production processes.

Siemens’ adoption of digital twin technology and IoT has revolutionized its approach to industrial automation, significantly decreasing time to market and operational costs while improving product quality and innovation. This strategic digital transformation has solidified Siemens’ position as a leader in smart industrial solutions, driving growth and sustainability in the sector.

21. Toyota: Pioneering Mobility Solutions with Connected Vehicle Technology

Toyota, a leading global automaker, sought to enhance vehicle safety, efficiency, and user experience by integrating advanced digital technologies into their vehicles, aiming to transition from a car manufacturer to a mobility solutions provider.

a. Connected Car Platform: Toyota developed a connected car platform that integrates telemetry, real-time data monitoring, and vehicle management systems to enhance the driving experience and improve vehicle maintenance.

b. Autonomous Driving Development: They significantly increased their investment in research and development for autonomous driving technologies to develop safer and more efficient transportation solutions.

c. Sustainable Mobility Solutions: Emphasizing sustainability, Toyota expanded its hybrid and electric vehicle offerings, supported by digital tools that help manage energy efficiency and reduce carbon emissions.

Toyota’s digital transformation has significantly improved vehicle functionality and safety, increasing customer satisfaction and loyalty. Their focus on connected and autonomous technologies has positioned Toyota at the forefront of the next generation of mobility solutions, driving innovation in the automotive industry.

22. Unilever: Digital Sustainability and Supply Chain Innovation

Background .

Unilever, a global leader in consumer goods, aimed to enhance its sustainability practices and supply chain efficiency by embedding digital technologies. This initiative supports their commitment to environmental sustainability and efficient resource management.

a. Sustainable Sourcing Platform: Unilever developed a digital platform to trace the sourcing of raw materials, ensuring they meet sustainability standards. This system helps manage supplier relationships and certifications, promoting ethical sourcing practices.

b. AI-Driven Demand Forecasting: Leveraging AI to improve demand forecasting accuracy, Unilever optimized production and inventory management, reducing waste and improving delivery timelines.

c. Eco-Efficient Operations: By implementing IoT devices in manufacturing facilities, Unilever monitors and reduces energy usage, water consumption, and carbon emissions, enhancing the environmental impact of its production processes.

Unilever’s digital sustainability and supply chain management initiatives have improved operational efficiencies and significantly advanced its corporate responsibility goals. These efforts have helped Unilever reduce its environmental footprint, increase transparency in its supply chain, and strengthen its brand reputation among eco-conscious consumers.

Related: Digital Transformation in Finance Case Studies

23. Philips: Transforming Healthcare with Connected Care Solutions

Philips, a global leader in health technology, focused on transforming the healthcare industry by integrating digital solutions into its products and services. This strategic change was designed to improve patient care and boost operational efficiency in healthcare facilities around the globe.

Transformation

a. Connected Health Devices: Philips expanded its line of connected health devices, including wearable technology for remote patient monitoring, that allows healthcare providers to track patient vitals and conditions in real time.

b. Cloud-Based Platforms: They developed cloud-based platforms that facilitate the sharing and analyzing of health data across systems, improving collaboration between healthcare professionals and enabling more informed decision-making.

c. AI-Enhanced Diagnostics: Implementing artificial intelligence in diagnostic equipment, Philips has improved the accuracy and speed of patient diagnostics, aiding in early detection and personalized treatment plans.

Philips’ digital transformation has significantly improved patient care and healthcare efficiency. Their connected care solutions have made health services more accessible, particularly in remote areas, and enhanced the ability of medical professionals to provide timely and effective treatment. This strategic digital integration supports Philips’ mission to improve billions of lives through meaningful innovation.

24. BASF: Driving Chemical Innovation with Digital Lab and Process Optimization

BASF, one of the largest chemical producers in the world, aimed to enhance innovation and efficiency in its chemical processes and product development by leveraging digital technologies. This initiative was a key component of their wider strategy to maintain a competitive advantage and promote sustainable operations.

a. Digital Labs: BASF implemented digital labs that use virtual simulations and modeling to accelerate chemical research and development, reducing the time and resources required for experimental trials.

b. Process Automation and IoT: They enhanced their manufacturing processes through advanced process automation integrated with IoT sensors, enabling for real-time monitoring and control of chemical processes, which improves safety and efficiency.

c. Predictive Maintenance: BASF implemented predictive maintenance capabilities in their facilities using machine learning algorithms. This technology anticipates equipment failures before they happen, reducing downtime and extending the life of their machinery.

BASF’s adoption of digital technologies in its laboratories and production facilities has significantly boosted innovation and operational efficiency. These advancements have enabled BASF to produce higher-quality chemical products faster and more sustainably, reinforcing its position as a leader in the global chemical industry.

25. Coca-Cola: Refreshing Consumer Engagement with Digital Marketing and Analytics

Coca-Cola, one of the world’s most iconic beverage brands, recognized the need to adapt to changing consumer behaviors and expectations, particularly in the digital age. They aimed to engage consumers more effectively and personalize their marketing efforts.

a. Digital Engagement Platforms: Coca-Cola developed digital platforms and mobile applications to engage directly with consumers, offering personalized promotions, loyalty rewards, and interactive brand experiences.

b. Data-Driven Marketing: Leveraging big data analytics, Coca-Cola refined its marketing strategies to target consumers more precisely based on their preferences and behaviors. This approach allowed for more effective ad placements and campaign optimizations.

c. Social Media Integration: Coca-Cola enhanced its presence by creating dynamic and interactive content tailored to global markets, increasing engagement and loyalty.

Coca-Cola’s digital transformation in marketing has significantly increased consumer engagement and brand visibility. Their use of advanced analytics and digital platforms has enabled more personalized and effective marketing campaigns, reinforcing Coca-Cola’s position as a leading global brand in the beverage industry.

Related: Digital Transformation in Aviation Case Studies

The stories of these 15 companies culminate in a powerful testament to the transformative impact of digital technology. Each case study highlights the pivotal role of innovation in securing market leadership and underscores the broader implications for industries at large. Through their transformative journeys, these firms reveal that achieving digital excellence is a challenging endeavor, yet it is abundant with opportunities for growth and reinvention. This collection serves as both a beacon and a warning: embracing change isn’t optional to thrive in the digital era; it’s imperative.

- Top 12 Free Marine Biology Courses [2024]

- Tim Walz Education [Deep Analysis][2024]

Team DigitalDefynd

We help you find the best courses, certifications, and tutorials online. Hundreds of experts come together to handpick these recommendations based on decades of collective experience. So far we have served 4 Million+ satisfied learners and counting.

12 Famous Female Leaders in Digital Transformation [2024]

Who is a Chief Transformation Officer? How to become one? [2024]

5 ways Digital Transformation is being used in Real Estate [2024]

5 Digital Transformation in Hotels Case Studies [2024]

15 Digital Transformation Failure Examples [2024]

Top 30 Chief Digital Officer (CDO) Interview Questions and Answers [2024]

- Perspectives

- Best Practices

- Inside Amplitude

- Customer Stories

- Contributors

Digital Transformation Case Studies: 3 Successful Brand Examples

Learn how three companies—Walmart, Ford, and Anheuser-Busch InBev—successfully transformed their business through digital initiatives to improve the customer experience.

Originally published on March 30, 2022

3 digital transformation case studies

Overcoming common digital transformation challenges, tips for building a digital transformation strategy, always focus on your customers.

Digital transformation is a process in which a company invests in new digital products and services to position it for growth and competition. A successful digital transformation improves the customer experience and enhances the way a company operates behind the scenes.

During a digital transformation, your business deploys new products and technologies and develops new ways to connect with your customers. Once the investment in digital begins, your business can use feedback and data to identify growth opportunities.

The three case studies below—from Ford, Walmart, and Anheuser-Busch InBev (AB InBev)—show how legendary companies went beyond simply creating an app and truly re-thought how digital transformation efforts supported sustainable growth for the business.

- A digital transformation is a major business transformation that employs technology to meet business goals and fundamentally change how companies operate.

- A digital transformation drives new products and services that improve the customer experience.

- A digital transformation gives you more informative behavioral data and more touchpoints with the customer.

- AB InBev, Walmart, and Ford invested in digital technology to accelerate internal processes and develop new digital products, which gave them valuable data on the customer experience and influenced future business investments.

Here are three examples of digital transformation. These leading companies carefully considered how new technology could generate data that made internal processes more efficient and produced insights about how to grow customer value.

Brewing company AB InBev underwent a digital transformation while compiling its network of independent breweries into a unified powerhouse . One of the team’s priorities was moving all their data to the cloud . By doing so, AB InBev enabled all employees to quickly and easily pull global insights and use them to make data-backed decisions.

For example, more accurate demand forecasting means AB InBev teams can match supply with demand, which is essential for such a large company with a complex supply chain. Access to big data from all the breweries means employees can experiment faster and roll out changes that improve business processes.

Gathering more data and opening up that data to internal teams was just the first step of the process, though. AB InBev capitalized on its digital investments by launching an e-commerce marketplace called BEES for its SMB customers—the “mom-and-pop shops”—to order products from. With the BEES platform, AB InBev found that their small and medium-sized businesses browsed the store on the mobile app and added items to their cart throughout the day. However, they only made the final purchases later in the evening.

Based on this behavioral data, the BEES team started sending push notifications after 6:00 p.m. recommending relevant products, which led to increased sales and greater customer satisfaction. Through these efforts, BEES gained over 1.8 million monthly active users and captured over $7.5B in Gross Merchandise Volume.

By closely monitoring metrics such as user engagement and purchasing patterns on the BEES platform, AB InBev has made a big impact with its marketing strategies and improved customer retention.

Jason Lambert, SVP of product at BEES, credits their success with the hard data that told them how their customers behaved and what they needed: “It turned out to be a thousand times better than any of our previous strategies or assumptions.” BEES used behavioral analytics to respond quickly, changing the buying experience to match the needs and habits of their retailers.

As a traditional brick-and-mortar retailer, Walmart began a digital transformation by opening an online marketplace. However, digital transformation is an ongoing process—it doesn’t end at the first website. A digital transformation means companies refocus their operations around digital technology. This usually happens both internally and in a customer-facing way.

To drive more customer value through digital touchpoints, Walmart set up mobile apps and a website to enable customers to purchase goods online. After analyzing customer behavioral information from its app, Walmart added more services such as same-day pickup, mobile ordering, and “buy now, pay later.”

These changes were made to meet customer expectations and improve the customer experience. Walmart’s introduction of a seamless online shopping experience represents a pivotal step in digital innovation, setting new standards for retail convenience and efficiency.

In 2024, Walmart announced an AI-powered logistics product called Route Optimization. This product uses AI to find the most straightforward driving routes, pack trailers efficiently, and reduce miles traveled. In addition to using this product internally, Walmart plans to offer it to other businesses that need to employ more efficient supply chain and logistic processes.

Aside from improving customer experience and logistics, Walmart’s head of mobile marketing , Sherry Thomas-Zon, also notes the importance of data—and access to data—in digital transformations. “Our marketing and product teams are always looking at numbers,” Thomas-Zon said. “It keeps our teams agile despite our size and the increasing amount of data we collect and analyze.”

Ford has embraced several digital transformation initiatives, including using technology to transform and improve manufacturing at one of its biggest automotive factories.

Not having the correct parts available holds up workers and slows down the production process. Ford introduced a material flow wireless parts system so they could track the quantities of different parts and make sure there were enough available. Ford’s use of automation has significantly improved its inventory management process by reducing manual tasks and enhancing worker efficiency.

In 2016, Ford also introduced a digital product for its customers: the FordPass app . It enables Ford owners to control their vehicles remotely. For example, drivers can check their battery or fuel levels and lock or unlock their cars from their phones.

In 2024, Ford took its digital transformation even further when it launched the Ford and Lincoln Digital Experience . Key features include personalized vehicle settings, real-time traffic updates, and seamless integration with smart home devices. The platform also provides advanced navigation, remote control of vehicle functions via the FordPass app, and in-depth vehicle health monitoring.

To capitalize on these digital touchpoints, Ford uses data from its app to improve user experiences . With the ability to capture and analyze data in real-time, Ford’s leadership can now make quicker, more informed decisions that directly enhance operational efficiency and customer satisfaction.

Ford’s success is grounded in the same process as Walmart and AB InBev. They used their digital transformation to gather detailed information about how customers interact with their products. Then, they made data-driven decisions to provide more value.

It’s not called a transformation for no reason. You’re changing the way your business operates, which is no easy feat. Planning and effective change management strategies are key to overcoming digital transformation challenges.

Create a digital transformation strategy roadmap that outlines your integration strategy and details how this will affect your teams, processes, and workflows. Once you’ve created your plan, share it with the entire company so everyone can use it as a single reference point. Use a project management tool that enables team members to get a big-picture overview and see granular details like the tasks they’re responsible for.

It takes time for teams to onboard and move away from what was successful under the previous system, for example, shifting from heavyweight to lightweight project planning. Make sure you factor some breathing space into your roadmap—giving everyone a chance to get used to the new way of operating.

As part of a digital transformation, you’ll want your team to develop new skills as well. Upskill your team by incorporating digital skills into your employee development plans . Provide people with opportunities to learn and then track their progress. Promote platforms like LinkedIn Learning to help your teams understand the nuances of digital transformation and boost their skills.

If you believe there’s an end-state to digital transformation, more challenges will arise. New technology and consumer behaviors are always emerging, meaning digital transformation is ongoing. It’s not something you’ll complete in a week. Rather, it’s a continuous state of experimentation and improvement.

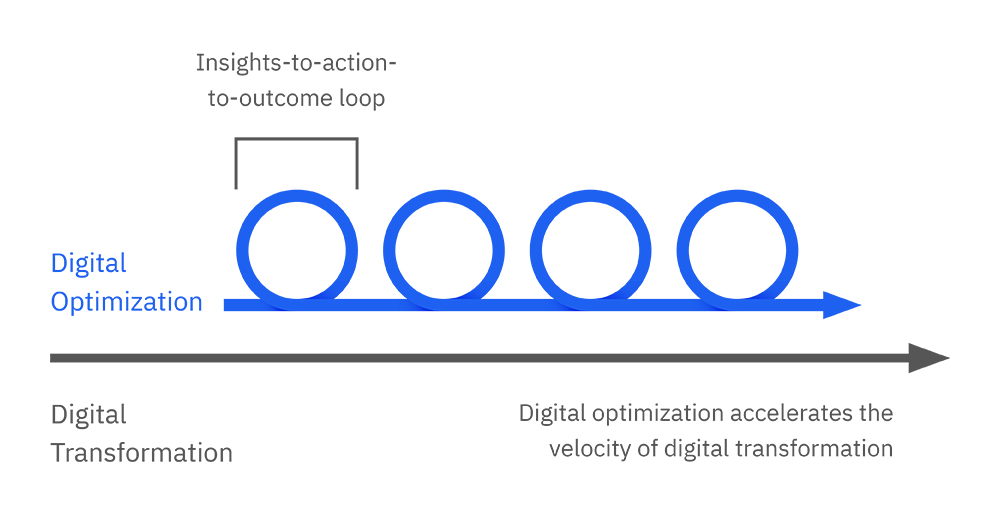

At Amplitude, we refer to this process as digital optimization . If digital transformation brings new products, services, and business models to the fold, then digital optimization is about improving these outputs. Both digital transformation and digital optimization are important—digital transformation signals the start of new investments, and digital optimization compounds them.

Examine how each part of the transformation will affect your customers and your employees. Then, you can be intentional and introduce initiatives that positively impact your business.

Diagnose what you want from a digital transformation first

There are different ways of approaching a digital transformation. Some companies prefer to implement an all-inclusive digital strategy, transforming all parts of their organization at the same time. Others opt for a less risky incremental strategy. Every company is different. To choose the best approach, examine your whole organization and analyze where digital systems could help.

Consider your business goals. Investigate how a digital transformation could impact the customer experience. What new products could you provide? How could you improve your services? For example, you might use artificial intelligence to create a chatbot that reduces customer service wait times—or purchase software that does the same.

You’ll also want to review your business processes. How could a digital transformation speed up your current workflows, improve your operations, or enable more collaboration between teams? Asking these questions lets you challenge the way you operate and will help you identify problems in your organization that you might not have noticed before. For example, perhaps your deliveries are often delayed, and you could make delivery smoother by digitizing elements of your supply chain .

Get cross-team involvement

Though different teams may work separately, your customers are affected by each department. Collaboration elevates everyone’s work because it means people can make informed decisions.

Make sure you get input from all of the right stakeholders when you create your digital transformation strategy. Ask:

- What processes hold you up?

- Where are the bottlenecks?

- What data would be useful for you?

Enable everyone to access the data they need without input from anyone else. Help your employees improve their data literacy . Start by training all your employees to use your organization’s data tools and software. To help everyone in your organization access and analyze data, adopt easy-to-use self-service tools (e.g., an analytics tool and a CRM). Then, lead by example. Provide inspiration by using data storytelling in your presentations to explain the decisions you make.

Encourage collaboration between teams by creating shared resources so they have spaces to present insights and submit suggestions. This could be as simple as creating a Google Doc for brainstorming that multiple teams can access or sharing charts directly within your analytics solution, like with Amplitude Notebooks . Then, you can start to experiment and make improvements to the digital customer experience like Walmart, Ford, and AB InBev did.

Once your digital transformation is moving, a digital optimization strategy is an opportunity to generate growth. Your digital transformation initiatives will continue in parallel, and the process will become a feedback loop:

- Deploy new digital systems and products.

- Analyze the data that comes forth from these investments. Use it to draw insights about your customers or processes.

- Make decisions based on the data and make changes.

Keep customer needs at the heart of your work. Let them guide you as you undergo digital transformation. As you gather more data about how your customers interact with your new digital products, use it to make the experience even better for them. This will lead to more trust and loyalty and, ultimately, more recurring revenue.

To continue your learning about digital transformation and optimization, join an Amplitude workshop or webinar or read our Guide to Digital Optimization .

- MIT Sloan. How to build data literacy in your company

- Ernst & Young. How global supply chain strategy is changing and what comes next

- Datanami. From Big Beer to Big Data: Inside AB InBev’s Digital Transformation

- Predictable Profits. How Ford Embraced Digital Transformation

- APMG International. Heavyweight vs Lightweight Management

About the Author

More best practices.

What is a Data Warehouse?

The guide to data accessibility, what is a product roadmap a definitive guide, new amplitude + snowflake integration delivers the modern data stack, digital optimization vs. digital transformation explained, 6 essential digital optimization skills you need, test-driven development (tdd) - what it is and how to implement it, use the games of product activity to define your engagement strategy.

30+ Digital Transformation Case Studies & Success Stories

Digital transformation has been on the executive agenda for the past decade and ~ 90% of companies have already initiated their first digital strategy. However, given the increasing pace of technological innovation, there are numerous areas to focus on. A lack of focus leads to failed initiatives. Digital transformation leaders need to focus their efforts but they are not clear about in which areas to focus their digital transformation initiatives.

We see that digital transformation projects focusing on customer service and operations tend to be more heavily featured in case studies and we recommend enterprises to initially focus on digitally transforming these areas.

Research findings:

- Outsourcing is an important strategy for many companies’ digital transformation initiatives.

- Most successful digital transformation projects focus on customer service and operations

Michelin-EFFIFUEL

Michelin, a global tire manufacturer, launched its EFFIFUEL initiative in 2013 to reduce the fuel consumption of trucks. In this context, vehicles were equipped with telematics systems that collect and process data on the trucks, tires, drivers habits and fuel consumption conditions. By analyzing this data, fleet managers and executives at the trucking companies were able to make adjustments to reduce oil consumption.

- Business challenge : Inability to improve customer retention rates to target levels, due to trucks’ fuel consumption and CO2 emissions .

- Target customers : Fleet managers and operations managers at truck companies in Europe

- Line of business function : Customer success management and sales.

- Solution : By using smart devices, truck and tire performance degradation is detected and maintained from the start. The solution also nudges truck drivers into more cost and environmentally friendly driving.

- Business result : Enhanced customer retention and satisfaction. EFFIFUEL has brought fuel savings of 2.5 liters per 100 kilometers per truck. The company also reduced the environmental costs of transportation activities. According to Michellin, if all European trucking companies had been using the EFFIFUEL initiative, it would have caused a 9 tons of CO2 emission reduction.

Schneider Electric-Box

Schneider Electric is a global company with employees all over the world. Prior to the Box initiative , which is a cloud-based solution, business processes were relatively slow because it is difficult to process the same documents from different locations at the same time. Schneider Electric also needed a way to provide data management and security for its globally dispersed workforce. So Schneider Electric outsourced its own custom cloud environment that integrates with Microsoft Office applications to Box. The platform also ensures tight control of corporate data with granular permissions, content controls and the use of shared links. Thanks to this initiative, the company has moved from 80% of its content hosted on-premises to 90% in the cloud and has a more flexible workforce.

- Business challenge : Inability to increase operational efficiency of the global workforce without capitulating to data security.

- Solution : Outsourcing company’s cloud-based platform to Box, that ensures data security and integration with Microsoft Office programs to ensure ease of doing business.

- Business result : Schneider Electric connects its 142.000 workers within one platform which hosts 90% of its documents.

Thomas Pink-Fits.me

British shirt maker Thomas Pink, part of the Louis Vuitton Moet Hennessey group, has outsourced the development of its online sales platform to Fits.me Virtual Fitting Room . The aim of the initiative was to gain a competitive advantage over its competitors in e-commerce. Thanks to the online platform developed, customers can determine how well the shirt they are buying fits them by entering their body size.

The platform also helps Fits.me gain better customer insight as previously unknown customer data, including body measurements and fit preferences, becomes available. In this way, the platform can offer customers the clothes that fit them better.

- Business challenge : Lack of visibility into online sales and customers’ preferences.

- Target customers : Online buyers and users.

- Line of business function : Sales and customer success management.

- Solution : Outsourcing the development of the online platform to Fits.me Virtual Fitting Room .

- Business result : Improved customer satisfaction and engagement. Thomas Pink reports that customers who enter the virtual fitting room are more likely to purchase a product than those who do not. There are many successful digital transformation projects from different industries, but we won’t go into every case study. Therefore, we provide you with a sortable list of 31 successful case studies. We categorized them as:

- System Improvement : changing the way existing businesses work by introducing new technologies.

- Innovation : creating new business practices, based on the latest technology.

| Type of Project | Company | Initiative | Industry | Business Function | Case Study | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System Improvement | Apple | CarPlay | Automotive | Customer Service | 37 million sales estimation in 2020 | |

| System Improvement | Audi | Audi City | Automotive | Marketing and Sales | ||

| Innovation | BMW | DriveNow | Automotive | Mobility Services | ||

| Innovation | Daimler | Moovel | Automotive | Mobility Services | Moovel has more than 1 million customers. | |

| System Improvement | Michellin | EFFIFUEL | Automotive | Customer Service | ||

| Innovation | Tesla | Automotive | Customer Service | Saving $2.7 billion for manufacturers. Improving customer experience. | ||

| System Improvement | Thomas Pink | Fits.me | Retail | Operations | 29.6% higher conversion rate | |

| Innovation | Lego | Entertainment | Operations | |||

| System Improvement | General Electric | Digital Windfarm | Energy | Operations | ||

| System Improvement | Schneider Electric | Box | Electricity | Operations | ||

| Innovation | Hospitals* | Ginger.io | Healthcare | Operations | ||

| Innovation | Cohealo | Healtcare | Operations | Improving clinical outcomes while reducing healthcare costs. | ||

| Innovation | Pager | Healthcare | Customer Service | |||

| System Improvement | Airbus | Transportation | Manufacturing | Using 3D printers for manufacturing plane parts | ||

| System Improvement | Disney | Disney's Magic Bands | Entertainment | Customer Service | Improved customer experience. Over 9 million visitors give positive feedback. | |

| System Improvement | Spotify | Entertainment | Customer Service | |||

| System Improvement | Communication | Operations | Improved customer experience | |||

| Innovation | Blippar | Technology | Operations | 45% revenue growth. | ||

| System Improvement | Start-ups* | Bolt.io | Consulting | Operations | ||

| System Improvement | Duolingo | Education | Operations | Delivering personalized education through its AI-powered language-learning platform. | Improved customer experience. More than 100 million users. | |

| System Improvement | Accredia | Accreditation | Customer service | Increased web traffic. Users find the desired information quicker. | ||

| Innovation | EdgePetrol | Palladium** | Analytics/Oil | Product development | ||

| Innovation | Mayflex | Palladium** | Security | Operations | ||

| Innovation | Starbucks | Beverages | Operations | Improved customer experience | ||

| System Improvement | Unilever | FMCG | Operations | |||

| System Improvement | Keller Williams | KW Labs | Real Estate | Operations | Over 20% y-o-y sales volume increase | |

| Innovation | IndusInd Bank | Banking | Operations | Creating digital branches and enabling social media banking transactions | Valued at approx.$1.5 billion and up 46% in value yoy | |

| System Improvement | Monsanto | Climate FieldView | Climate/Agriculture | Operations | Farmers benefit from better yields, lower risks and higher profitability. | |

| System Improvement | BBVA | Banking | Customer Service | |||

| System Improvement | Nokia | QPR ProcessAnalyzer | Telecommunication | Operations | Shortened lead time due to increased efficiency in running processes | |

| System Improvement | Eneco Group (Joulz) | QPR Suite | Energy | Operations |

If you are ready to start you digital transformation journey, you can check our data-driven and comprehensive list of digital transformation consultant companies .

To find out more about digital transformation, you can also read our digital transformation best practices , digital transformation roadmap and digital transformation culture articles.

You can also check our sustainability case studies article which include ESG related success stories.

For any further assistance please contact us:

This article was drafted by former AIMultiple industry analyst Görkem Gençer.

Next to Read

10 best use cases of process mining utilities , healthcare apis: top 7 use cases & challenges with examples, top 5 digital technologies transforming the energy sector.

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.

Related research

5 Digital Technologies Transforming The Oil & Gas Sector in ’23

AI Transformation : In-Depth guide for executives

DBS: Transforming a banking leader into a technology leader

Jump to Section: Opportunity | Solution | Impact | Lessons learned

Keep Exploring

Creating value beyond the hype

The solution.

To embody the vision of becoming a technology leader, the DBS team adopted the mnemonic GANDALF, representing the giants of the tech industry: "G" for Google, "A" for Amazon, "N" for Netflix, "A" for Apple, "L" for LinkedIn, and "F" for Facebook. The central "D" symbolizes DBS aspiration to join the league of iconic technology companies. Drawing inspiration from The Lord of the Rings , GANDALF became the powerful rallying cry for their ambitious digital transformation journey. Throughout these efforts, DBS kept the focus firmly on the customer.

To scale up capabilities, McKinsey aided DBS in building its new operating model around platforms. DBS created 33 platforms aligned to business segments and products. Each platform had a “2-in-a-box” leadership model, which meant each one was jointly led by a leader from the business and one from IT.

“Digital transformation has been instrumental in driving growth, delivering significant financial outcomes across all business segments and markets. By transforming rigid systems into nimble technology stacks, we have gained a sustainable advantage, enabling us to scale with agility.” – Jimmy Ng, Chief Information Officer and Group Head of Technology & Operations, DBS