- Library & Learning Center

- Research Guides

- Abortion Research

Start Learning About Your Topic

Create research questions to focus your topic, featured current news, find articles in library databases, find web resources, find books in the library catalog, cite your sources, key search words.

Use the words below to search for useful information in books and articles .

- birth control

- pro-choice movement

- pro-life movement

- reproductive rights

- Roe v. Wade

- Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization (Dobbs v. Jackson)

Background Reading:

It's important to begin your research learning something about your subject; in fact, you won't be able to create a focused, manageable thesis unless you already know something about your topic.

This step is important so that you will:

- Begin building your core knowledge about your topic

- Be able to put your topic in context

- Create research questions that drive your search for information

- Create a list of search terms that will help you find relevant information

- Know if the information you’re finding is relevant and useful

If you're working from off campus , you'll be prompted to sign in if you aren't already logged in to your MJC email or Canvas. If you are prompted to sign in, use the same credentials you use for email and Canvas.

Most current background reading

- Issues and Controversies: Should Women in the United States Have Access to Abortion? June 2022 article (written after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v Wade) that explores both sides of the abortion debate.

- Access World News: Abortion The most recent news and opinion on abortion from US newspapers.

More sources for background information

- CQ Researcher Online This link opens in a new window Original, comprehensive reporting and analysis on issues in the news. Check the dates of results to be sure they are sufficiently current.

- Gale eBooks This link opens in a new window Authoritative background reading from specialized encyclopedias (a year or more old, so not good for the latest developments).

- Gale In Context: Global Issues This link opens in a new window Best database for exploring the topic from a global point of view.

Choose the questions below that you find most interesting or appropriate for your assignment.

- Why is abortion such a controversial issue?

- What are the medical arguments for and against abortion?

- What are the religious arguments for and against abortion?

- What are the political arguments for and against abortion?

- What are the cultural arguments for and against abortion?

- What is the history of laws concerning abortion?

- What are the current laws about abortion?

- How are those who oppose access to abortion trying to affect change?

- How are those who support access to abortion trying to affect change?

- Based on what I have learned from my research, what do I think about the issue of abortion?

- State-by-State Abortion Laws Updated regularly by the Guttmacher Institute

- What the Data Says About Abortion in the U.S. From the Pew Research Center in March of 2024, a look at the most recent available data about abortion from sources other than public opinion surveys.

Latest News on Abortion from Google News

All of these resources are free for MJC students, faculty, & staff.

- Gale Databases This link opens in a new window Search over 35 databases simultaneously that cover almost any topic you need to research at MJC. Gale databases include articles previously published in journals, magazines, newspapers, books, and other media outlets.

- EBSCOhost Databases This link opens in a new window Search 22 databases simultaneously that cover almost any topic you need to research at MJC. EBSCO databases include articles previously published in journals, magazines, newspapers, books, and other media outlets.

- Facts on File Databases This link opens in a new window Facts on File databases include: Issues & Controversies , Issues & Controversies in History , Today's Science , and World News Digest .

- MEDLINE Complete This link opens in a new window This database provides access to top-tier biomedical and health journals, making it an essential resource for doctors, nurses, health professionals and researchers engaged in clinical care, public health, and health policy development.

- Access World News This link opens in a new window Search the full-text of editions of record for local, regional, and national U.S. newspapers as well as full-text content of key international sources. This is your source for The Modesto Bee from January 1989 to the present. Also includes in-depth special reports and hot topics from around the country. To access The Modesto Bee , limit your search to that publication. more... less... Watch this short video to learn how to find The Modesto Bee .

Browse Featured Web Sites:

- American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists Medical information and anti-abortion rights advocacy.

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Use the key term "abortion" in the search box on this site for links to reports and statistics.

- Guttmacher Institute Statistics and policy papers with a world-wide focus from a "research and policy organization committed to advancing sexual and reproductive health and rights worldwide."

- NARAL Pro-Choice America This group advocates for pro-abortion rights legislation. Current information abortion laws in the U.S.

- National Right to Life Committee This group advocates for anti-abortion rights legislation in the U.S.

Why Use Books:

Use books to read broad overviews and detailed discussions of your topic. You can also use books to find primary sources , which are often published together in collections.

Where Do I Find Books?

You'll use the library catalog to search for books, ebooks, articles, and more.

- OneSearch (Library Catalog) OneSearch provides simple, one-stop searching for books and e-books, videos, articles, digital media, and more.

What if MJC Doesn't Have What I Need?

If you need materials (books, articles, recordings, videos, etc.) that you cannot find in the library catalog, use our interlibrary loan service.

- Interlibrary Loan Borrowing materials from other libraries is simple and free.

Your instructor should tell you which citation style they want you to use. Click on the appropriate link below to learn how to format your paper and cite your sources according to a particular style.

- Chicago Style

- ASA & Other Citation Styles

- Last Updated: Nov 13, 2024 11:57 AM

- URL: https://libguides.mjc.edu/abortion

Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 and CC BY-NC 4.0 Licenses .

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Reducing the harms of unsafe abortion: a systematic review of the safety, effectiveness and acceptability of harm reduction counselling for pregnant persons seeking induced abortion

Bianca maria stifani, roopan gill, caron rahn kim.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence to Dr Bianca Maria Stifani, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY 10532, USA; [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Received 2021 Oct 13; Accepted 2021 Dec 11; Issue date 2022 Apr.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

Globally, access to safe abortion is limited. We aimed to assess the safety, effectiveness and acceptability of harm reduction counselling for abortion, which we define as the provision of information about safe abortion methods to pregnant persons seeking abortion.

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, ClinicalTrials.gov, Cochrane, Global Index Medicus and the grey literature up to October 2021. We included studies in which healthcare providers gave pregnant persons information on safe use of abortifacient medications without providing the actual medications. We conducted a descriptive summary of results and a risk of bias assessment using the ROBINS-I tool. Our primary outcome was the proportion of pregnant persons who used misoprostol to induce abortion rather than other methods among those who received harm reduction counselling.

We included four observational studies with a total of 4002 participants. Most pregnant persons who received harm reduction counselling induced abortion using misoprostol (79%–100%). Serious complication rates were low (0%–1%). Uterine aspiration rates were not always reported but were in the range of 6%–22%. Patient satisfaction with the harm reduction intervention was high (85%–98%) where reported. We rated the risk of bias for all studies as high due to a lack of comparison groups and high lost to follow-up rates.

Based on a synthesis of four studies with serious methodological limitations, most recipients of harm reduction counselling use misoprostol for abortion, have low complication rates, and are satisfied with the intervention. More research is needed to determine abortion success outcomes from the harm reduction approach.

This work did not receive any funding.

PROSPERO registration number

We registered the review in the PROSPERO database of systematic reviews (ID number: CRD42020200849).

Keywords: abortion, induced, patient safety, abortifacient agents

Key messages.

This review article examines abortion harm reduction interventions, or the provision of information about how to safely induce abortion without the provision of actual medications.

Most pregnant persons who participate in these interventions use misoprostol to induce abortion.

Based on few studies of poor quality, it appears that persons who participate in these interventions have low complication and high satisfaction rates.

Introduction

Globally, access to safe abortion is limited. As a result, an estimated 25 million unsafe abortion occur each year, and at least 22 800 women die from resulting complications, almost all in low- and middle-income countries. 1 This is often due to restrictive laws which prohibit abortion; but even in contexts where abortion is legal, other barriers, such as cost, distance and regulatory barriers, may limit access to services. 2

One approach to mitigating the consequences of unsafe abortion where traditional clinician-directed abortion care is not an option has been to provide pregnant persons seeking abortion with harm reduction counselling. While the term ‘harm reduction’ is most often used in the context of substance abuse, it can be more broadly understood as a set of interventions that reduce the negative effects of certain health behaviours without seeking to completely eliminate those behaviours. 3

In the context of abortion, the term has been used to describe interventions aimed at providing pregnant persons seeking abortion with information about how to safely self-administer abortifacient medications. This often includes risk assessment or screening and follow-up medical care, but does not include providing the actual medications. 2 This strategy is considered promising because, while eradicating unsafe abortions may not be immediately feasible, particularly in legally restrictive settings, providing information to make abortions safer may reduce the burden of unsafe abortion morbidity.

In the early 2000s, physicians in Uruguay used a ‘risk reduction strategy’ to address the problem of maternal morbidity and mortality due to unsafe abortion. They offered women who were considering an abortion a ‘pre-abortion’ counselling visit, during which they imparted information about how to safely administer misoprostol, and a ‘post-abortion’ follow-up visit. They reported very low complication rates and used their programme to advocate for legal change in the country. 4 The programme eventually served as a framework for providing safe abortion care once abortion was legalised. 5

Other approaches to applying a harm reduction framework to abortion have included providing information through telephone hotlines, 6 7 training pharmacists to assess for medical abortion eligibility, 8 and distributing misoprostol through community-based organisations. 9

In this review we focus on harm reduction counselling, which we define as the direct provision of information to pregnant persons seeking abortion. The purpose of the systematic review is to assess the safety, effectiveness and acceptability of harm reduction counselling for pregnant persons seeking induced abortion. This review is needed because there is increasing interest in using harm reduction approaches to improve access to abortion in legally and otherwise restrictive settings, 2 but a thorough review of the evidence in favour of harm reduction counselling does not currently exist.

Search strategy

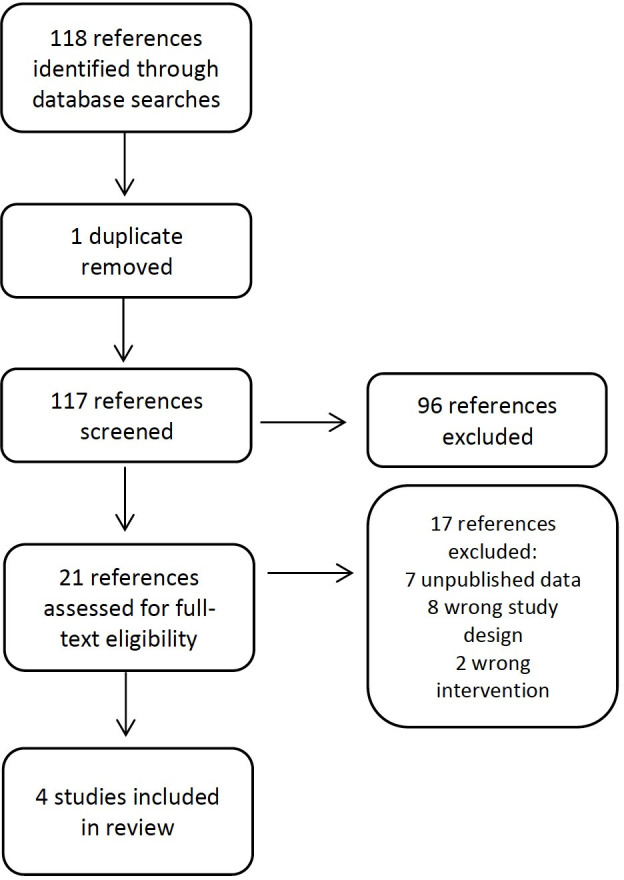

We conducted a systematic search of published studies in PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, Clinicaltrials.gov and Global Index Medicus. We also searched the grey literature for relevant studies (OpenGray, Google Scholar). We performed the initial search in July 2020 and did not exclude studies based on language, setting or timing of publication. We repeated the search and updated the study diagram in October 2021. We used search constructs appropriate for each database (see online supplemental file 1 ). We uploaded citations in Mendeley and removed duplicates prior to uploading citations to Covidence. Two researchers (BMS and RG) performed title and abstract screening of all studies, and full-text screening of studies that seemed to meet the inclusion criteria. We resolved any conflicts via discussion until reaching consensus, and a third researcher (CRK) intervened when conflicts could not be resolved by the first two researchers. We report our methods and results in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). 10

bmjsrh-2021-201389supp001.pdf (38.5KB, pdf)

Study selection

We defined harm reduction in the context of abortion as the direct provision (by any kind of healthcare provider) of information about safe abortion methods to pregnant persons seeking induced abortion. We included published studies that were primary studies, including randomised trials, cohort and case-control studies and cross-sectional studies. We included studies that reported on outcomes relating to the effectiveness, safety and acceptability of harm reduction counselling; also studies of any sample size and with any type of comparison group, including no comparison group. Included studies had to report on our primary outcome, which was the proportion of pregnant persons who used misoprostol for abortion. We chose this as our primary outcome because we considered use of misoprostol to be the most important marker of safe abortion, and our primary objective was to evaluate harm reduction counselling as a strategy to reduce the harms of unsafe abortion. Our secondary outcomes were:

The proportion of users who had an abortion (utilising any method) after harm reduction counselling

The proportion of users who had a complete abortion after taking misoprostol

The proportion of users who had an aspiration procedure after taking misoprostol

The proportion of users who had complications, defined as infection not requiring intravenous (IV) antibiotics or hospital admission; haemorrhage or prolonged bleeding not requiring transfusion

The proportion of users who had serious complications, defined as infection requiring IV antibiotics or hospital admission; haemorrhage requiring blood transfusion or other complication requiring hospital admission, other than simply for aspiration

The proportion of users who attended a follow-up visit

The proportion of users who were satisfied with the harm reduction counselling they received

The proportion of users who were using a contraceptive method after harm reduction counselling

Ease of obtaining misoprostol

Location where misoprostol was obtained.

We excluded studies describing other approaches aimed at reducing the harms of unsafe abortion if they did not involve direct counselling of pregnant persons within the healthcare system (eg, the provision of information via hotlines or to pharmacists). We also excluded approaches that provided pregnant persons with the actual abortifacient medications or abortion procedures (eg, community-based distribution of misoprostol) as the purpose of this review was to evaluate the effectiveness of harm reduction counselling . We excluded commentaries, editorials, letters, advisories, conference abstracts and review articles.

Study synthesis and assessment

One researcher (BMS) extracted data on outcomes compatible with our predefined outcomes. We performed a narrative synthesis of the reported outcome results.

Two researchers (BMS and RG) independently conducted a risk of bias assessment for all included studies using the ROBINS-I tool for assessing risk of bias in nonrandomized studies of interventions ( box 1 ). The tool includes seven bias domains: bias due to confounding, selection bias, bias in classification of interventions, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing data, bias in measurement of outcomes, and bias in selection of the reported result. 11

Box 1. ROBINS-I tool for assessing risk of bias in nonrandomized studies of interventions.

Bias due to confounding

Bias in selection of participants into the study

Bias in classification of interventions

Bias due to deviations from intended interventions

Bias due to missing data

Bias in measurement of outcomes

Bias in selection of the reported results

For each domain, we rated the risk of bias as either low, high or unclear. Of note, for bias due to missing data, we selected a 25% lost to follow-up cut-off point for a definition of high risk of bias. Any conflicts between the two researchers were resolved by a third researcher (CRK). We searched for trial protocols and registration prior to making judgement on the reporting biases.

We could not perform a meta-analysis because of the overall quality and heterogeneity of the included studies, which differed significantly in terms of outcomes reported and means of assessing outcomes.

Registration

We registered the review in the PROSPERO database of systematic reviews (ID number: CRD42020200849). The review protocol is accessible through the database.

Characteristics of included studies

We identified 118 studies through database and grey literature searches. We excluded 96 references because they did not meet inclusion criteria, while 21 studies met criteria for full-text review. Of these, we excluded 17, as shown in the PRISMA diagram ( figure 1 ). Of note, we excluded two articles that reported as their only outcome a changing rate in maternal mortality that coincided with the implementation of a harm reduction intervention. 12 13 We included four studies in the review, which were conducted in three countries. All were observational studies with no comparison groups, and the harm reductions interventions were similar ( table 1 ).

PRISMA study flow diagram.

LMP: last menstrual period; US: ultrasound

LMP, Last menstrual period; US, ultrasound.

The first study was conducted at one public hospital in Uruguay and included 675 women who received harm reduction counselling, of whom 73% completed a follow-up visit. 4 The intervention included pregnancy confirmation, gestational age assessment by ultrasound, and information about how to use misoprostol.

The 2016 study by the same group describes a scale-up of the same strategy to eight public health centres in four departments in Uruguay. 14 Although 2717 women received the intervention, only 27% attended a follow-up visit. The authors did not state why the lost to follow-up rate was significantly higher than in their 2006 study.

The third selected study was conducted in Tanzania. 15 The intervention differed in that ultrasound was only used to assess gestational age if the pregnant person did not remember the date of their last menstrual period. This study had a clinical follow-up component, and a separate survey of a convenience sample of 50 participants. Of the 110 patients enrolled, 50% completed follow-up.

The fourth study was conducted in Peru. 16 The intervention was similar to that described in the Uruguayan studies, except that participants could select telephone or in-person follow-up. This study also included a survey and presented survey results separately from those of the clinical follow-up. Of the 500 patients included, only 35% completed in-person or telephone follow-up. Outcomes of interest to this review are reported for 253 of the 500 patients (51%) who completed the survey.

Synthesis of results

The four selected studies included a total of 4002 participants, but outcomes were only available for participants who completed follow-up, 4 14 for participants who completed follow-up or responded to a research survey, 14 or only for participants who responded to a research survey 17 ( table 2 ).

Summary of included studies by outcome reported

*Complications are defined as infection not requiring intravenous (IV) antibiotics or hospital admission; haemorrhage or prolonged bleeding not requiring transfusion.

†Serious complications are defined as infection requiring IV antibiotics or hospital admission; haemorrhage requiring blood transfusion; any other complication requiring hospital admission other than simply for aspiration.

‡Note: proportion who completed follow-up is only reported for those who completed the survey and took misoprostol; there may be people who followed up in person or via telephone but did not complete the survey but this is not reported.

§This was the primary outcome for the review.

GA, gestational age; IV, intravenous.

For the primary outcome, the proportion of pregnant persons who used misoprostol to induce abortion, rates varied from 79% (as reported in the survey component of the Kahabuka et al study) to 100% in the Briozzo et al 2006 study. 4 14 Of note, 100% of the participants who completed clinical follow-up in the Kahabuka study used misoprostol. 15

In terms of secondary outcomes, the proportion of participants who proceeded to induce an abortion after counselling ranged from 88% to 96%. 4 15 16 All studies reported low complication rates, and none reported any deaths. A total of 71/4002 participants had complications (overall complication rate 1.8%) but only two had serious complications – hospital admission for treatment of infection. All other complications were considered mild and included post-abortion infection not requiring intravenous antibiotics or hospital admission, haemorrhage not requiring blood transfusion, pain, and prolonged bleeding. The complication rate ranged from 0.6% to 8% whereas the serious complication rate was 0%–1%.

Two studies reported uterine aspiration rates, which ranged from 6% to 22%. 15 16 One study reported that the aspiration rate decreased over time, from 30% to 18%, but did not report an overall aspiration rate. 4 The complete abortion without aspiration rate was only explicitly reported in one study 16 and was 66%, but for 24/220 (11%) participants the outcome was unsure at the time of interview.

Two studies reported on the ease of obtaining misoprostol and found that 52%–87% of participants found it very or somewhat easy to obtain. 15 16 The same studies also reported on the location where misoprostol was obtained and found that 80%–90% of participants obtained it from pharmacies. 15 16

Three of the four studies reported on participant satisfaction with the harm reduction counselling intervention, with satisfaction rates ranging from 85% to 98%. 14–16

Three of the four studies reported on contraceptive initiation rates after the harm reduction counselling visits: these ranged from 55% to 76% of participants using a contraceptive method. 14–16

Quality of the evidence

We rated the quality of the evidence for all selected outcomes as low, because all the included studies were observational and did not include comparison groups. Further, the primary outcome, which was the proportion of pregnant persons who used misoprostol to induce abortion, was self-reported in all four studies. Because there were no comparison groups, we rated the risk of bias in classification of interventions as low for all studies. For several of the biases included in the ROBINS-I tool, the selected studies did not offer sufficient information to accurately assess the risk of bias.

Loss to follow-up rates were high in all four studies, which meant that bias due to missing data was high. Three of the four studies conducted some analysis of the participants lost to follow-up. For one of the studies conducted in Uruguay, 14 the authors contacted a convenience sample of 94 of the 1988 women who did not return for follow-up and found that only 53.2% had a termination, while 21.3% chose to continue the pregnancy (the proportion who induced abortion among those who did follow up is not explicitly reported). The authors of the study conducted in Tanzania 15 compared characteristics of the 55 users who did not follow up and the 55 users who did and found no statistically significant differences between the groups. The third study 16 compared participants who followed up in person to those who followed up via telephone and to those who did not receive any follow-up. Participants recruited at a more rural site were less likely to follow up in person and more likely to follow up via telephone; those who did not follow up were less likely to have felt comfortable asking questions at the consultation and less likely to recommend the services to a friend or use it again if necessary.

Three of the studies did not have published research protocols, and we were therefore unable to assess the bias in selection of the reported results. For the remaining study 16 we did find a conference abstract outlining the research protocol, based on which we rated bias in selection of the reported results as low. Table 3 summarises our risk of bias ratings for the selected studies according to the seven biases included in the ROBINS-I tool.

Risk of bias assessment according to the seven biases included in the ROBINS-I tool

In this review we found that of the relatively few pregnant persons who followed up after receiving harm reduction counselling, most induced an abortion using misoprostol, and did so with extremely low complication rates. Where reported, patient satisfaction with this approach appeared to be high, and misoprostol appeared easy to obtain, mostly from pharmacies. Abortion completion and uterine aspiration rates, where reported, varied widely.

Although these results are limited by the quality of the studies included, they do align with previous studies which have reported on the overall safety and high patient satisfaction rates with medical abortion. It is well known that complication rates from medical abortion are low, 18 19 even when misoprostol is used without mifepristone, 20 as was the case in the four studies included in this review. Patient satisfaction tends to be high after abortion in general, regardless of whether the abortion is medical or surgical. 21 When it comes to medical abortion, satisfaction is high regardless of the means by which the care is provided – in-person or telemedicine 22 23 – or the type of provider. 17

Harm reduction counselling as implemented in these studies is one of several strategies that have been used to support pregnant persons seeking abortion in legally or otherwise restrictive contexts. While this review focused on counselling by healthcare providers, other strategies exist, including hotlines, 6 7 smartphone interventions, 24 accompaniment networks 25 and community-based distribution of misoprostol. 9 The evidence base for most of these strategies appears to be limited, in part because many are implemented at the grassroots level rather than in academic circles, and in part because it is difficult to engage abortion patients in research, particularly in legally restrictive settings. 26 This leads to high lost to follow-up rates, as we found in all the studies included in this review. A systematic review of telemedicine for medical abortion similarly reported high lost to follow-up rates (up to 57%) in the included studies. The authors commented that users who are lost to follow-up may have lower complication rates, and that studies conducted among patients who are accessing healthcare outside the formal health sector will inevitably have high attrition rates. 22 Their conclusions are relevant for this review of harm reduction counselling, and we similarly caution policymakers to consider the best available evidence despite its limitations.

Another limitation of these studies is that there was significant heterogeneity in terms of how abortion completion was assessed. One study used an evidence-based questionnaire for self-assessment 16 while another used a “medical examination”, 15 and the remaining two did not specify if and how this outcome was assessed. Also, uterine aspiration rates were not universally reported. Where they were, they varied from 6% to 22%. 15 16 The 22% aspiration rate is higher than what would be expected based on the reported efficacy of the misoprostol alone regimen for early medical abortion as reported in large clinical trials (84%–85%). 27 Other studies have previously reported that aspiration rates for women who access telemedicine services for abortion vary according to their region of residence, with women in Latin America reporting high aspiration rates, even in the absence of symptoms. 28 29 That the aspiration rate in Tanzania was significantly lower (6%) is an encouraging finding, 15 suggesting that the need for uterine aspiration following harm reduction counselling and subsequent medical abortion may in fact be low. However, these results require further investigation.

Finally, the lack of comparison groups in these studies limit what can be said about harm reduction counselling’s ability to reduce the risks of unsafe abortion. However, given that all of these studies were conducted in legally restrictive settings, the lack of a comparison group is understandable as no comparison group could have been accessible or ethically included in research. A few articles which did not meet the study design inclusion criteria for this review describe nationwide decreases in maternal mortality rates (and particularly maternal mortality due to unsafe abortion) in Uruguay and Argentina, which coincided in time with the widespread implementation of harm reduction counselling for abortion. 11 12 This finding is promising, but the implementation of harm reduction approaches cannot be isolated from other interventions which may also have contributed to a decrease in mortality due to unsafe abortion, such as the increase in availability of misoprostol and the use of telemedicine and telephone hotline services for medical abortion. 29 30

Given the methodological limitations we found in the studies included in this review, we recommend a few strategies to improve the quality of the evidence in future studies on this topic. First, researchers should consider recruiting and following up with participants using various modalities, including smartphone applications or text messaging. 26 Financial or other incentives may help improve follow-up rates where deemed ethically appropriate. Finally, researchers should report on study outcomes that are listed in the core outcome set for abortion research, 31 and clearly outline how the outcomes are assessed.

Conclusions

Based on a synthesis of limited evidence with serious methodological limitations, provision of harm reduction counselling to pregnant persons seeking induced abortion seems to be highly acceptable to service users, and the reported complication rates are low. Ultimately, harm reduction counselling lies on a spectrum that goes from traditional clinician-directed, in-person care to complete self-management of medical abortion. Much like hotlines, pharmacist training, and community-based distribution of misoprostol, this strategy aims to provide some support to patients whose access to abortion would otherwise be limited. The available evidence does not allow us to compare harm reduction counselling to these other strategies that could be adopted in similarly restrictive settings. However, it does suggest that harm reduction counselling can safely be considered, particularly by clinicians who wish to provide some support to pregnant persons seeking induced abortion but are constrained by local laws and regulations.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the development of the review protocol. BMS performed the systematic search. BMS and RG assessed the studies for eligibility and conducted the risk of bias assessment. BMS performed the main analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RG and CRK contributed to the interpretation of the results and the revisions of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclaimer: The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants.

- 1. Ganatra B, Gerdts C, Rossier C, et al. Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010–14: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. The Lancet 2017;390:2372–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31794-4 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Tasset J, Harris LH. Harm reduction for abortion in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:621–4. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002491 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Hawk M, Coulter RWS, Egan JE, et al. Harm reduction principles for healthcare settings. Harm Reduct J 2017;14:70. 10.1186/s12954-017-0196-4 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Briozzo L, Vidiella G, Rodríguez F, et al. A risk reduction strategy to prevent maternal deaths associated with unsafe abortion. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2006;95:221–6. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.07.013 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Stifani BM, Couto M, Lopez Gomez A. From harm reduction to legalization: the Uruguayan model for safe abortion. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2018;143 Suppl 4:45–51. 10.1002/ijgo.12677 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Gerdts C, Hudaya I. Quality of care in a safe-abortion hotline in Indonesia: beyond harm reduction. Am J Public Health 2016;106:2071–5. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303446 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Gill RK, Cleeve A, Lavelanet AF. Abortion hotlines around the world: a mixed-methods systematic and descriptive review. Sex Reprod Health Matters 2021;29:1907027. 10.1080/26410397.2021.1907027 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Tamang A, Puri M, Masud S, et al. Medical abortion can be provided safely and effectively by pharmacy workers trained within a harm reduction framework: Nepal. Contraception 2018;97:137–43. 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.09.004 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Coeytaux F, Hessini L, Ejano N, et al. Facilitating women's access to misoprostol through community-based advocacy in Kenya and Tanzania. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2014;125:53–5. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.10.004 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016;355:i4919. 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Matía MG, Trumper EC, Fures NO, et al. A replication of the Uruguayan model in the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina, as a public policy for reducing abortion-related maternal mortality. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2016;134:S31–4. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.06.008 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Briozzo L, Gómez Ponce de León R, Tomasso G, et al. Overall and abortion-related maternal mortality rates in Uruguay over the past 25 years and their association with policies and actions aimed at protecting women’s rights. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2016;134:S20–3. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.06.004 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Labandera A, Gorgoroso M, Briozzo L. Implementation of the risk and harm reduction strategy against unsafe abortion in Uruguay: from a university hospital to the entire country. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2016;134:S7–11. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.06.007 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Kahabuka C, Pembe A, Meglioli A. Provision of harm-reduction services to limit unsafe abortion in Tanzania. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2017;136:210–4. 10.1002/ijgo.12035 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Grossman D, Baum SE, Andjelic D, et al. A harm-reduction model of abortion counseling about misoprostol use in Peru with telephone and in-person follow-up: a cohort study. PLoS One 2018;13:e0189195. 10.1371/journal.pone.0189195 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Tamang A, Shah IH, Shrestha P, et al. Comparative satisfaction of receiving medical abortion service from nurses and auxiliary nurse-midwives or doctors in Nepal: results of a randomized trial. Reprod Health 2017;14:176. 10.1186/s12978-017-0438-7 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Sanhueza Smith P, Peña M, Dzuba IG, et al. Safety, efficacy and acceptability of outpatient mifepristone-misoprostol medical abortion through 70 days since last menstrual period in public sector facilities in Mexico City. Reprod Health Matters 2015;22:75–82. 10.1016/S0968-8080(15)43825-X [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Chen MJ, Creinin MD. Mifepristone with buccal misoprostol for medical abortion: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:12–21. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000897 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Raymond EG, Harrison MS, Weaver MA. Efficacy of misoprostol alone for first-trimester medical abortion: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:137–47. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003017 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Harvey SM, Beckman LJ, Satre SJ. Choice of and satisfaction with methods of medical and surgical abortion among U.S. clinic patients. Fam Plann Perspect 2001;33:212–6. 10.2307/2673784 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Endler M, Lavelanet A, Cleeve A, et al. Telemedicine for medical abortion: a systematic review. BJOG 2019;126:1094–102. 10.1111/1471-0528.15684 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Grindlay K, Lane K, Grossman D, Women’s GD. Women’s and providers’ experiences with medical abortion provided through telemedicine: a qualitative study. Women's Health Issues 2013;23:e117–22. 10.1016/j.whi.2012.12.002 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Gerdts C, Jayaweera RT, Kristianingrum IA, et al.Effect of a smartphone intervention on self-managed medication abortion experiences among safe-abortion hotline clients in Indonesia: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2020;149:48–55. 10.1002/ijgo.13086 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Zurbriggen R, Keefe-Oates B, Gerdts C. Accompaniment of second-trimester abortions: the model of the feminist Socorrista network of Argentina. Contraception 2018;97:108–15. 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.07.170 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Kapp N, Blanchard K, Coast E, et al. Developing a forward-looking agenda and methodologies for research of self-use of medical abortion. Contraception 2018;97:184–8. 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.09.007 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Huong NTM, et al. Efficacy of two intervals and two routes of administration of misoprostol for termination of early pregnancy: a randomised controlled equivalence trial. Lancet 2007;369:1938–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60914-3 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Gomperts R, Petow SAM, Jelinska K, et al. Regional differences in surgical intervention following medical termination of pregnancy provided by telemedicine. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2012;91:226–31. 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01285.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Gomperts R, van der Vleuten K, Jelinska K, et al. Provision of medical abortion using telemedicine in Brazil. Contraception 2014;89:129–33. 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.11.005 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Dzuba IG, Winikoff B, Peña M. Medical abortion: a path to safe, high-quality abortion care in Latin America and the Caribbean. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2013;18:441–50. 10.3109/13625187.2013.824564 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Whitehouse KC, Stifani BM, Duffy JMN, et al. Standardizing abortion research outcomes (STAR): results from an international consensus development study. Contraception 2021;104:484–91. 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.07.004 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- View on publisher site

- PDF (596.5 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

What the data says about abortion in the U.S.

Pew Research Center has conducted many surveys about abortion over the years, providing a lens into Americans’ views on whether the procedure should be legal, among a host of other questions.

In a Center survey conducted nearly a year after the Supreme Court’s June 2022 decision that ended the constitutional right to abortion , 62% of U.S. adults said the practice should be legal in all or most cases, while 36% said it should be illegal in all or most cases. Another survey conducted a few months before the decision showed that relatively few Americans take an absolutist view on the issue .

Find answers to common questions about abortion in America, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Guttmacher Institute, which have tracked these patterns for several decades:

How many abortions are there in the U.S. each year?

How has the number of abortions in the u.s. changed over time, what is the abortion rate among women in the u.s. how has it changed over time, what are the most common types of abortion, how many abortion providers are there in the u.s., and how has that number changed, what percentage of abortions are for women who live in a different state from the abortion provider, what are the demographics of women who have had abortions, when during pregnancy do most abortions occur, how often are there medical complications from abortion.

This compilation of data on abortion in the United States draws mainly from two sources: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Guttmacher Institute, both of which have regularly compiled national abortion data for approximately half a century, and which collect their data in different ways.

The CDC data that is highlighted in this post comes from the agency’s “abortion surveillance” reports, which have been published annually since 1974 (and which have included data from 1969). Its figures from 1973 through 1996 include data from all 50 states, the District of Columbia and New York City – 52 “reporting areas” in all. Since 1997, the CDC’s totals have lacked data from some states (most notably California) for the years that those states did not report data to the agency. The four reporting areas that did not submit data to the CDC in 2021 – California, Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey – accounted for approximately 25% of all legal induced abortions in the U.S. in 2020, according to Guttmacher’s data. Most states, though, do have data in the reports, and the figures for the vast majority of them came from each state’s central health agency, while for some states, the figures came from hospitals and other medical facilities.

Discussion of CDC abortion data involving women’s state of residence, marital status, race, ethnicity, age, abortion history and the number of previous live births excludes the low share of abortions where that information was not supplied. Read the methodology for the CDC’s latest abortion surveillance report , which includes data from 2021, for more details. Previous reports can be found at stacks.cdc.gov by entering “abortion surveillance” into the search box.

For the numbers of deaths caused by induced abortions in 1963 and 1965, this analysis looks at reports by the then-U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, a precursor to the Department of Health and Human Services. In computing those figures, we excluded abortions listed in the report under the categories “spontaneous or unspecified” or as “other.” (“Spontaneous abortion” is another way of referring to miscarriages.)

Guttmacher data in this post comes from national surveys of abortion providers that Guttmacher has conducted 19 times since 1973. Guttmacher compiles its figures after contacting every known provider of abortions – clinics, hospitals and physicians’ offices – in the country. It uses questionnaires and health department data, and it provides estimates for abortion providers that don’t respond to its inquiries. (In 2020, the last year for which it has released data on the number of abortions in the U.S., it used estimates for 12% of abortions.) For most of the 2000s, Guttmacher has conducted these national surveys every three years, each time getting abortion data for the prior two years. For each interim year, Guttmacher has calculated estimates based on trends from its own figures and from other data.

The latest full summary of Guttmacher data came in the institute’s report titled “Abortion Incidence and Service Availability in the United States, 2020.” It includes figures for 2020 and 2019 and estimates for 2018. The report includes a methods section.

In addition, this post uses data from StatPearls, an online health care resource, on complications from abortion.

An exact answer is hard to come by. The CDC and the Guttmacher Institute have each tried to measure this for around half a century, but they use different methods and publish different figures.

The last year for which the CDC reported a yearly national total for abortions is 2021. It found there were 625,978 abortions in the District of Columbia and the 46 states with available data that year, up from 597,355 in those states and D.C. in 2020. The corresponding figure for 2019 was 607,720.

The last year for which Guttmacher reported a yearly national total was 2020. It said there were 930,160 abortions that year in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, compared with 916,460 in 2019.

- How the CDC gets its data: It compiles figures that are voluntarily reported by states’ central health agencies, including separate figures for New York City and the District of Columbia. Its latest totals do not include figures from California, Maryland, New Hampshire or New Jersey, which did not report data to the CDC. ( Read the methodology from the latest CDC report .)

- How Guttmacher gets its data: It compiles its figures after contacting every known abortion provider – clinics, hospitals and physicians’ offices – in the country. It uses questionnaires and health department data, then provides estimates for abortion providers that don’t respond. Guttmacher’s figures are higher than the CDC’s in part because they include data (and in some instances, estimates) from all 50 states. ( Read the institute’s latest full report and methodology .)

While the Guttmacher Institute supports abortion rights, its empirical data on abortions in the U.S. has been widely cited by groups and publications across the political spectrum, including by a number of those that disagree with its positions .

These estimates from Guttmacher and the CDC are results of multiyear efforts to collect data on abortion across the U.S. Last year, Guttmacher also began publishing less precise estimates every few months , based on a much smaller sample of providers.

The figures reported by these organizations include only legal induced abortions conducted by clinics, hospitals or physicians’ offices, or those that make use of abortion pills dispensed from certified facilities such as clinics or physicians’ offices. They do not account for the use of abortion pills that were obtained outside of clinical settings .

(Back to top)

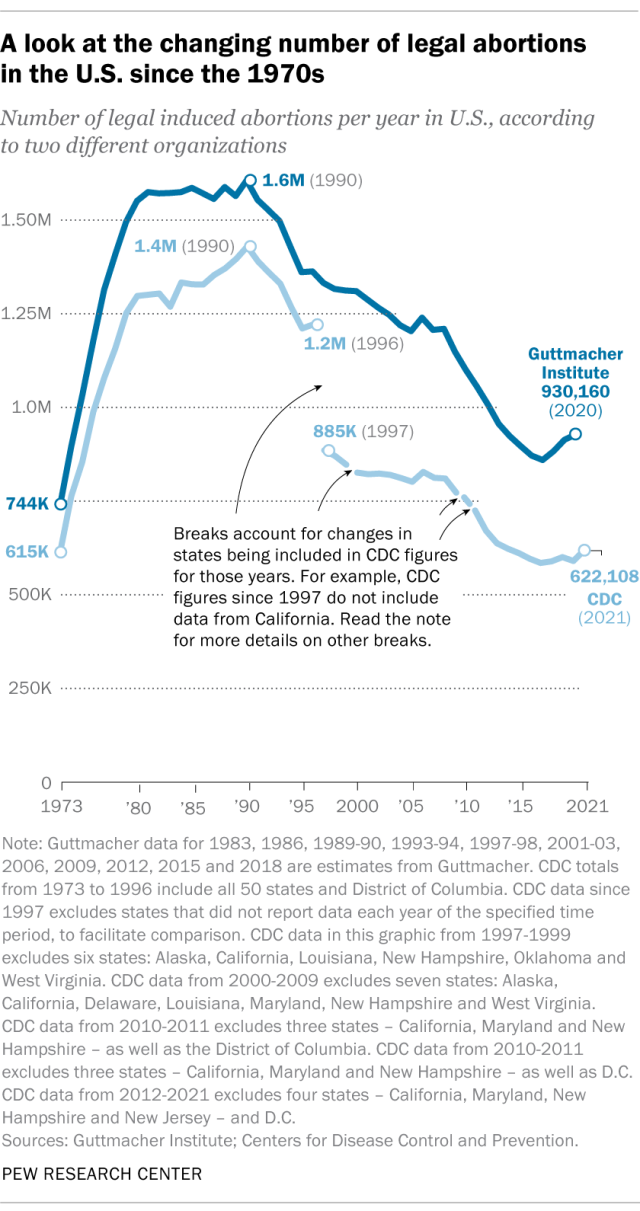

The annual number of U.S. abortions rose for years after Roe v. Wade legalized the procedure in 1973, reaching its highest levels around the late 1980s and early 1990s, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher. Since then, abortions have generally decreased at what a CDC analysis called “a slow yet steady pace.”

Guttmacher says the number of abortions occurring in the U.S. in 2020 was 40% lower than it was in 1991. According to the CDC, the number was 36% lower in 2021 than in 1991, looking just at the District of Columbia and the 46 states that reported both of those years.

(The corresponding line graph shows the long-term trend in the number of legal abortions reported by both organizations. To allow for consistent comparisons over time, the CDC figures in the chart have been adjusted to ensure that the same states are counted from one year to the next. Using that approach, the CDC figure for 2021 is 622,108 legal abortions.)

There have been occasional breaks in this long-term pattern of decline – during the middle of the first decade of the 2000s, and then again in the late 2010s. The CDC reported modest 1% and 2% increases in abortions in 2018 and 2019, and then, after a 2% decrease in 2020, a 5% increase in 2021. Guttmacher reported an 8% increase over the three-year period from 2017 to 2020.

As noted above, these figures do not include abortions that use pills obtained outside of clinical settings.

Guttmacher says that in 2020 there were 14.4 abortions in the U.S. per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44. Its data shows that the rate of abortions among women has generally been declining in the U.S. since 1981, when it reported there were 29.3 abortions per 1,000 women in that age range.

The CDC says that in 2021, there were 11.6 abortions in the U.S. per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44. (That figure excludes data from California, the District of Columbia, Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey.) Like Guttmacher’s data, the CDC’s figures also suggest a general decline in the abortion rate over time. In 1980, when the CDC reported on all 50 states and D.C., it said there were 25 abortions per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44.

That said, both Guttmacher and the CDC say there were slight increases in the rate of abortions during the late 2010s and early 2020s. Guttmacher says the abortion rate per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44 rose from 13.5 in 2017 to 14.4 in 2020. The CDC says it rose from 11.2 per 1,000 in 2017 to 11.4 in 2019, before falling back to 11.1 in 2020 and then rising again to 11.6 in 2021. (The CDC’s figures for those years exclude data from California, D.C., Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey.)

The CDC broadly divides abortions into two categories: surgical abortions and medication abortions, which involve pills. Since the Food and Drug Administration first approved abortion pills in 2000, their use has increased over time as a share of abortions nationally, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher.

The majority of abortions in the U.S. now involve pills, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher. The CDC says 56% of U.S. abortions in 2021 involved pills, up from 53% in 2020 and 44% in 2019. Its figures for 2021 include the District of Columbia and 44 states that provided this data; its figures for 2020 include D.C. and 44 states (though not all of the same states as in 2021), and its figures for 2019 include D.C. and 45 states.

Guttmacher, which measures this every three years, says 53% of U.S. abortions involved pills in 2020, up from 39% in 2017.

Two pills commonly used together for medication abortions are mifepristone, which, taken first, blocks hormones that support a pregnancy, and misoprostol, which then causes the uterus to empty. According to the FDA, medication abortions are safe until 10 weeks into pregnancy.

Surgical abortions conducted during the first trimester of pregnancy typically use a suction process, while the relatively few surgical abortions that occur during the second trimester of a pregnancy typically use a process called dilation and evacuation, according to the UCLA School of Medicine.

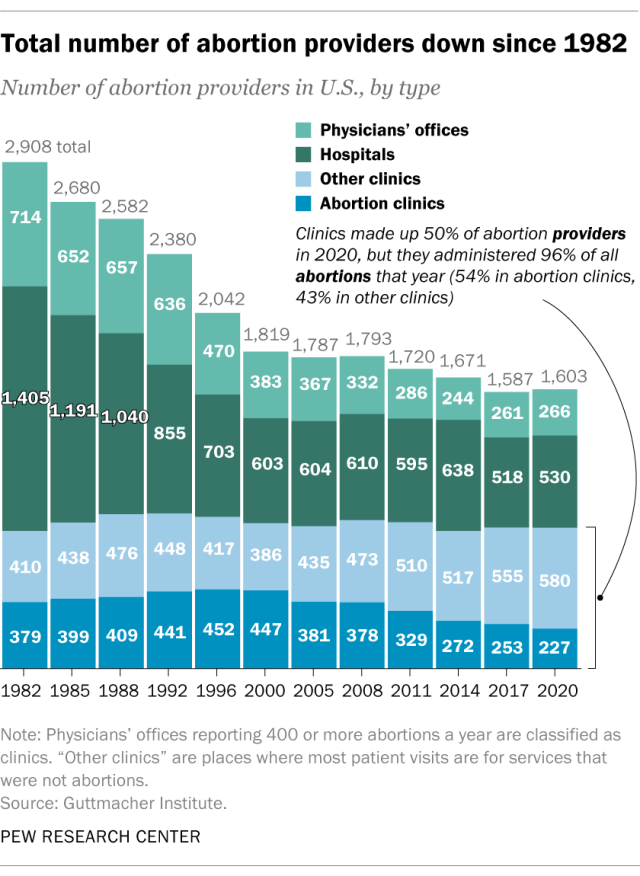

In 2020, there were 1,603 facilities in the U.S. that provided abortions, according to Guttmacher . This included 807 clinics, 530 hospitals and 266 physicians’ offices.

While clinics make up half of the facilities that provide abortions, they are the sites where the vast majority (96%) of abortions are administered, either through procedures or the distribution of pills, according to Guttmacher’s 2020 data. (This includes 54% of abortions that are administered at specialized abortion clinics and 43% at nonspecialized clinics.) Hospitals made up 33% of the facilities that provided abortions in 2020 but accounted for only 3% of abortions that year, while just 1% of abortions were conducted by physicians’ offices.

Looking just at clinics – that is, the total number of specialized abortion clinics and nonspecialized clinics in the U.S. – Guttmacher found the total virtually unchanged between 2017 (808 clinics) and 2020 (807 clinics). However, there were regional differences. In the Midwest, the number of clinics that provide abortions increased by 11% during those years, and in the West by 6%. The number of clinics decreased during those years by 9% in the Northeast and 3% in the South.

The total number of abortion providers has declined dramatically since the 1980s. In 1982, according to Guttmacher, there were 2,908 facilities providing abortions in the U.S., including 789 clinics, 1,405 hospitals and 714 physicians’ offices.

The CDC does not track the number of abortion providers.

In the District of Columbia and the 46 states that provided abortion and residency information to the CDC in 2021, 10.9% of all abortions were performed on women known to live outside the state where the abortion occurred – slightly higher than the percentage in 2020 (9.7%). That year, D.C. and 46 states (though not the same ones as in 2021) reported abortion and residency data. (The total number of abortions used in these calculations included figures for women with both known and unknown residential status.)

The share of reported abortions performed on women outside their state of residence was much higher before the 1973 Roe decision that stopped states from banning abortion. In 1972, 41% of all abortions in D.C. and the 20 states that provided this information to the CDC that year were performed on women outside their state of residence. In 1973, the corresponding figure was 21% in the District of Columbia and the 41 states that provided this information, and in 1974 it was 11% in D.C. and the 43 states that provided data.

In the District of Columbia and the 46 states that reported age data to the CDC in 2021, the majority of women who had abortions (57%) were in their 20s, while about three-in-ten (31%) were in their 30s. Teens ages 13 to 19 accounted for 8% of those who had abortions, while women ages 40 to 44 accounted for about 4%.

The vast majority of women who had abortions in 2021 were unmarried (87%), while married women accounted for 13%, according to the CDC , which had data on this from 37 states.

In the District of Columbia, New York City (but not the rest of New York) and the 31 states that reported racial and ethnic data on abortion to the CDC , 42% of all women who had abortions in 2021 were non-Hispanic Black, while 30% were non-Hispanic White, 22% were Hispanic and 6% were of other races.

Looking at abortion rates among those ages 15 to 44, there were 28.6 abortions per 1,000 non-Hispanic Black women in 2021; 12.3 abortions per 1,000 Hispanic women; 6.4 abortions per 1,000 non-Hispanic White women; and 9.2 abortions per 1,000 women of other races, the CDC reported from those same 31 states, D.C. and New York City.

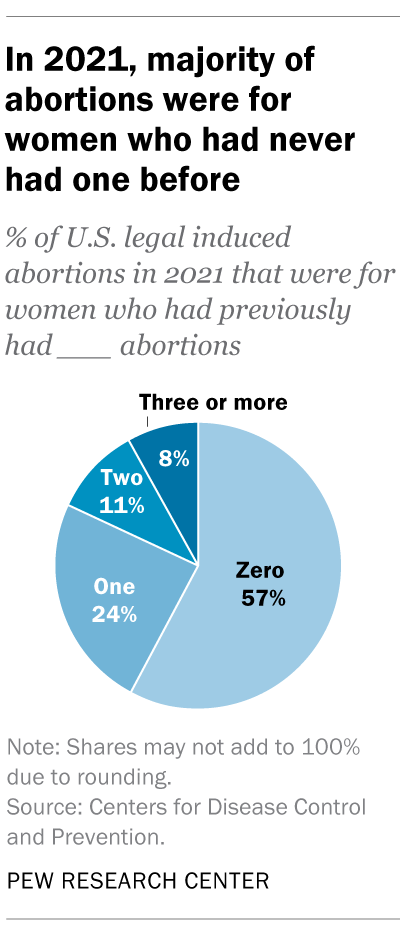

For 57% of U.S. women who had induced abortions in 2021, it was the first time they had ever had one, according to the CDC. For nearly a quarter (24%), it was their second abortion. For 11% of women who had an abortion that year, it was their third, and for 8% it was their fourth or more. These CDC figures include data from 41 states and New York City, but not the rest of New York.

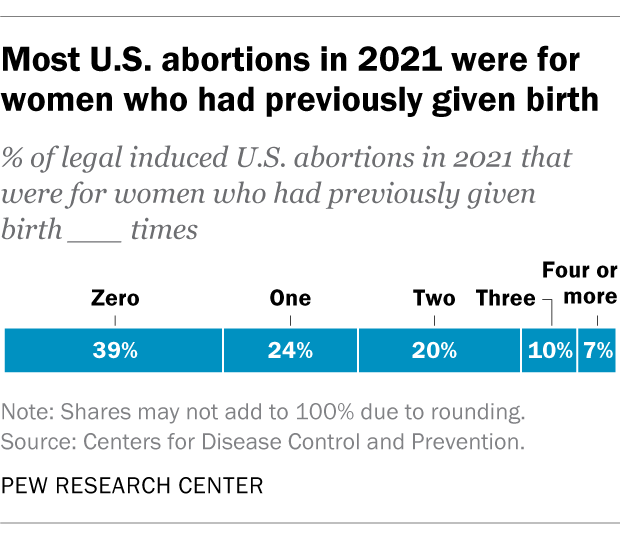

Nearly four-in-ten women who had abortions in 2021 (39%) had no previous live births at the time they had an abortion, according to the CDC . Almost a quarter (24%) of women who had abortions in 2021 had one previous live birth, 20% had two previous live births, 10% had three, and 7% had four or more previous live births. These CDC figures include data from 41 states and New York City, but not the rest of New York.

The vast majority of abortions occur during the first trimester of a pregnancy. In 2021, 93% of abortions occurred during the first trimester – that is, at or before 13 weeks of gestation, according to the CDC . An additional 6% occurred between 14 and 20 weeks of pregnancy, and about 1% were performed at 21 weeks or more of gestation. These CDC figures include data from 40 states and New York City, but not the rest of New York.

About 2% of all abortions in the U.S. involve some type of complication for the woman , according to an article in StatPearls, an online health care resource. “Most complications are considered minor such as pain, bleeding, infection and post-anesthesia complications,” according to the article.

The CDC calculates case-fatality rates for women from induced abortions – that is, how many women die from abortion-related complications, for every 100,000 legal abortions that occur in the U.S . The rate was lowest during the most recent period examined by the agency (2013 to 2020), when there were 0.45 deaths to women per 100,000 legal induced abortions. The case-fatality rate reported by the CDC was highest during the first period examined by the agency (1973 to 1977), when it was 2.09 deaths to women per 100,000 legal induced abortions. During the five-year periods in between, the figure ranged from 0.52 (from 1993 to 1997) to 0.78 (from 1978 to 1982).

The CDC calculates death rates by five-year and seven-year periods because of year-to-year fluctuation in the numbers and due to the relatively low number of women who die from legal induced abortions.

In 2020, the last year for which the CDC has information , six women in the U.S. died due to complications from induced abortions. Four women died in this way in 2019, two in 2018, and three in 2017. (These deaths all followed legal abortions.) Since 1990, the annual number of deaths among women due to legal induced abortion has ranged from two to 12.

The annual number of reported deaths from induced abortions (legal and illegal) tended to be higher in the 1980s, when it ranged from nine to 16, and from 1972 to 1979, when it ranged from 13 to 63. One driver of the decline was the drop in deaths from illegal abortions. There were 39 deaths from illegal abortions in 1972, the last full year before Roe v. Wade. The total fell to 19 in 1973 and to single digits or zero every year after that. (The number of deaths from legal abortions has also declined since then, though with some slight variation over time.)

The number of deaths from induced abortions was considerably higher in the 1960s than afterward. For instance, there were 119 deaths from induced abortions in 1963 and 99 in 1965 , according to reports by the then-U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, a precursor to the Department of Health and Human Services. The CDC is a division of Health and Human Services.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published May 27, 2022, and first updated June 24, 2022.

Jeff Diamant is a senior writer/editor focusing on religion at Pew Research Center .

Besheer Mohamed is a senior researcher focusing on religion at Pew Research Center .

Rebecca Leppert is a copy editor at Pew Research Center .

Cultural Issues and the 2024 Election

Support for legal abortion is widespread in many places, especially in europe, public opinion on abortion, americans overwhelmingly say access to ivf is a good thing, broad public support for legal abortion persists 2 years after dobbs, most popular.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

IMAGES