How to Write a Band 6 Discursive for Module C

Whether you've written 0 or 60 discursive pieces, this guide will help you polish your skills.

Shreya Mukherjee

5th in Eng Adv at Cheltenham Girls, UNSW Co-op Scholar

When starting Module C, many students end up Googling “how to write a discursive”. Honestly, that’s probably how you ended up here.

We can all agree that the rules of discursive writing are very confusing and seemingly contradictory. It needs to explore a particular topic, but without pushing an opinion! It’s meant to have a relatively informal tone, but make sure it’s not too informal! It’s meant to contain some figurative language, but ensure it doesn’t evolve into a creative! And as the cherry-on-top, the non-defined structure of discursive, makes the whole thing so much more confusing.

But don’t worry! This guide will take you through some key tips and tricks that help you write your own discursive.

Why you should write a discursive?

Before jumping into actual tips, our first tip is to take a step back . Don’t overcomplicate it too much. Out of all the text types you might choose to write in Module C (persuasive, informative, creative, discursive), discursive pieces are probably the most flexible . They’re free-flowing, giving you agency over how you write, and what you write about! You also don’t need to memorise quotes or do any analysis.

So, if an exam stimulus seems to be quite open-ended with many viewpoints, a discursive is a great way to explore these ideas.

With that in mind, let’s jump into the technicalities.

What is a discursive piece?

According to NESA:

Discursive texts are those whose primary focus is to explore an idea or variety of topics. These texts involve the discussion of an idea(s) or opinion(s) without the direct intention of persuading the reader, listener or viewer to adopt any single point of view. Discursive texts can be humorous or serious in tone and can have a formal or informal register. These texts include texts such as feature articles, creative nonfiction, blogs, personal essays, documentaries and speeches.

Now let’s break this down. A discursive piece first and foremost, is a discussion of ideas about a certain topic.

Picture this: You’re ranting to your friend about your favourite pizza flavour. Then along the way, you start discussing the best ways to make pizza. And then you might discuss the ethical nature of sourcing certain products attributed to pizza, and then you round up the discussion by talking about how pizza flavour preference correlates to personality (e.g. a no-fuss person might opt for a plain cheese pizza). You end off the discussion, with a striking realisation that everyone has their own preferences (not just with pizza, but with anything in life), because we’re all unique individuals, with our own identities.

You may be wondering, “how is discursive writing different to other text types?”.

NESA also explains some of the features specific to discursive writing . For instance, discursive texts often:

Explore an issue or an idea and may suggest a position or point of view

Approach a topic from different angles and explore themes and issues in a style that balances personal observations with different perspectives

Use personal anecdotes and may have a conversational tone

Primarily use first person although third person can also be used

Use figurative language or may be more factual

Draw upon real-life experiences and/or draws from wide reading

Use engaging imagery and language features

Begin with an event, an anecdote or relevant quote that is then used to explore an idea

Include a resolution that may be reflective or open-ended

Unlike with persuasive essays, you are not aiming to push a particular opinion or viewpoint. Unlike with an imaginative writing, you are not crafting a story with characters. Unlike with an informative piece, you are not trying to educate with non-fictional statements.

So, loosely speaking, discursive writing is intentionally-structured ranting about a random topic.

1. Brainstorming ideas

So how should you start? The first step is to find a topic which you don’t particularly care about (so you aren’t tempted to push a particular opinion/side - it’s not a persuasive essay), but a topic that is interesting enough to write about. I found these steps helpful:

List 10 - 15 ideas that seem interesting.

Create a shortlist by reviewing and eliminating ideas that are:

Too complicated to discuss in 1000-1200 words

Doesn’t give you the opportunity to explore multiple angles

Plain boring to write about

Hard to research, and you don’t know enough information about

Briefly research each topic in your shortlist, and narrow it down to the best one.

2. Structuring your discursive

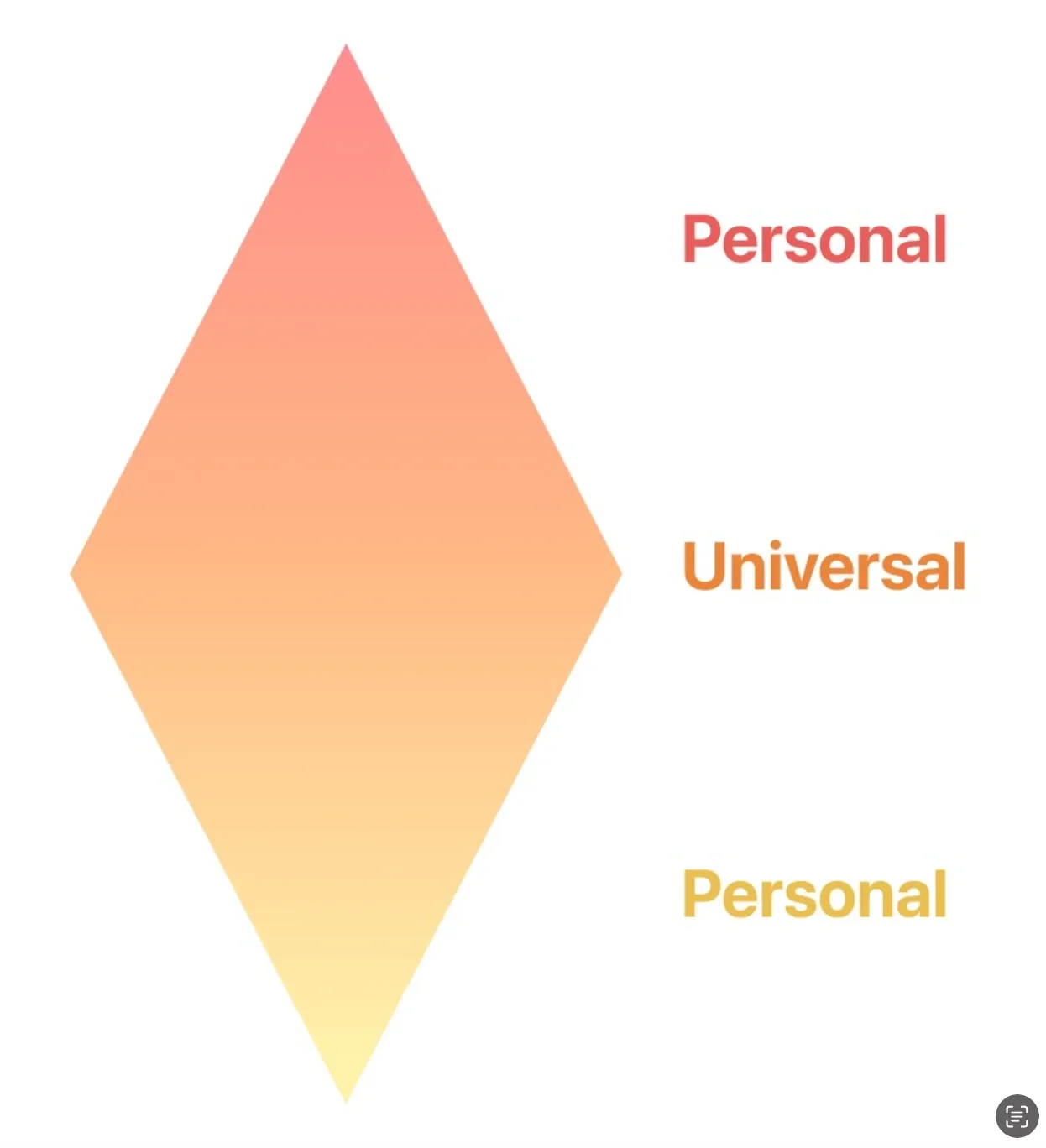

Unlike other text types, there is no “basic structure” or PEEL/PETAL to guide you. However, a diamond-shaped structure may help:

A suggested structure for discursive writing.

This signifies that you start with a personal anecdote (a short retelling of a personal experience - usually funny or interesting). Then, you branch out into a broader universal idea. Finally, tie it back in by referring to the same personal anecdote.

By doing this, your discursive essay will smoothly explore a train of thought without seeming like jumbled word vomit. The universal section also lets you explore other ideas and perspectives, which is crucial for a discursive response, according to NESA.

3. Using personal anecdotes

Unlike regular essays, discursive writing does not require you to integrate supporting evidence (e.g. quotes or literary analysis). In its place, we recommend that you use anecdotes (a feature of discursives, according to NESA). Why? They have two important benefits.

It allows the reader to form an emotional connection with you.

Niche personal experiences tend to act as a microcosm for something bigger. By introducing the anecdote, you’re encouraging the reader to reflect on the topic more broadly.

For instance, with the pizza example, the anecdotal retelling of YOUR favourite pizza flavour, eventually leads the reader to think about the concept of individual preference, and how everyone is different.

This then begs the question - what makes a good anecdote?

- Start with something random.

Many students fall into the trap of trying to find “the perfect anecdote”. However, ANY personal experience can be a good anecdote, from the most mundane encounter with your local barista, to a life-changing conversation with a famous person.

Don’t take it too seriously! Instead, think of something random, and then see if you can link it to your discursive idea.

Often, an exercise I would do with my English class at Project Academy , was to use a random word generator . We would then begin our discursive essays with an anecdote based on that concept.

- Choose an anecdote that also acts as a metaphor.

Ideally, you’re able to extract a metaphor from the anecdote, to weave throughout your discursive piece.

An example of this is seen in Margaret Atwood’s 1994 speech, “Spotty Handed Villainesses” (yes, I’m sorry to pull out the prescribed texts). Atwood compares the anecdote of watching a play about breakfast, to the value of literature within our life. If this metaphor doesn’t make sense, I highly encourage you to go read it!

By drawing comparisons between our personal lives to the idea being discussed, you’re adding a layer of complexity to your discursive essay. These extra details are what pushes a Band 5 discursive into the Band 6 region.

Let’s see this in action!

I’ve attached an example below, where I started my discursive talking about definite integrals, and then linked that to the value of literature (bizarre, I know, but it works).

Example: An anecdote on Definite Integrals

I think you would wonder why I have named my piece after a mathematical concept so niche, that it has no relevance in English. Well, except for one. Definite integrals are designed to estimate, but also to definitively find the area of a curve. And how does it do this? Through rectangles. Yes, rectangles. In Maths class, I learnt that this simple, straight-edged, four-sided shape could be used to find the area under the most complex curves one could possibly think of. I thought to myself, “whoever invented this is a total GENIUS!”. I was impressed that the solution was so out-of-the-box. But I was even more impressed that the answer to such a complex problem, rested on something so simple. Now, when I struggle to uncover the meaning within an English text I’m studying in class, trying to decipher what the author wanted us to realise, I simply consider rectangles. I try to step outside the box of literal meaning. Instead, I holistically take the text as a rectangle, to understand the values, characters, ideas, and representations within the text.

4. Branching out to a “universal” perspective

This section forms the “body” part of your discursive essay. Here, it’s important to take multiple perspectives on the topic that you’re discussing.

Alternative perspectives can be interjected in many ways, they can be introduced through a book, a notable person in that field, a journalist, general statistics, or even through your own ideas! According to the NESA excerpt mentioned earlier, you can get these other perspectives, from “wide reading”. Often good discursives will contain a mixture of these tools.

REMEMBER: your discursive should not present these ideas as “for vs. against” a certain topic - this is not a persuasive essay. An effective discursive will consider the different viewpoints , without pitching them against each other.

Think of it like a spectrum of ideas rather than just 2 opposing ideas about a topic.

Another key tip is to ensure between each idea or perspective has a smooth transition, to create flow. To do this, use a conversational tone to direct the reader through each key point (as if you’re speaking to a friend), or use your established metaphor to link between different sections.

5. Get inspiration by reading other discursives

The best way to improve discursive writing is to read a LOT of discursive texts.

In doing so, you can get a sense of voice, and writing style, which you can mirror in your own writing. This is also why reading your friend’s discursive is so mutually beneficial - you get to develop your discursive-writing skills, while they get to hear feedback!

PS: The Project Academy Books app (a resource database, home to hundreds of files and other goodies) has heaps of discursive essays to read through. Those enrolled in their HSC English course also receive access to unlimited marking from experienced tutors, who can provide valuable feedback to drafts.

Where to find examples of good discursive writing?

NESA’s prescribed list of texts for “Module C: The Craft of Writing” , including:

Geraldine Brooks’ ‘A Home in Fiction’

Margaret Atwood’s ‘Spotty-Handed Villainesses’ speech

Newspapers, such as Sydney Morning Herald (and other places publishing “political writing” pieces)

6. Writing a conclusion

As mentioned in our previous discussion, the “universal” section is followed by a link to your original anecdote, guiding the reader back to a more “personal” perspective. A nice way to conclude the long train of thought in your discursive, is to finish in ambiguous, and open-ended way.

The goal is to prompt the reader to think about what you’ve discussed, and form their own opinions.

For example, this excerpt below is from a discursive about how society has forgotten the value of literature, because of other entertainment options. Earlier in the discursive, a personal anecdote was introduced, about borrowing a friend’s book, and then forgetting to read it for 6 months. Notice how it flows from a “wider” angle, to a more personal ending.

In our modern world, we need stories more than ever before. To re-ground us, and to remind us of who we are. After all, our personal narratives and identities are a mere amalgamation of our experiences, a mere compilation of snippets in time, begging to be preserved in ink. That’s what it means to be human. Whilst I say all this, another Netflix movie blares from my laptop, with retrospectively mediocre characters and a strangely predictable plotline. Perhaps it is time to pick up Charlie’s novel and read it.

I hope this discursive guide helped!

Remember: there are no real rules when it comes to discursive essays. Whilst that seems like a bad thing, it’s actually GREAT for you. Don’t get too caught up on what the “perfect” discursive looks like. Be creative, write using your own style and voice, and talk about whatever you want!

The best way to get good at this, is just to start writing.

HSC English Advanced: Textual Conversations - The Tempest and Hag-Seed

Katriel's guide to The Tempest and Hag-Seed in Module A, HSC English Advanced!

English Team

Katriel Tan and Marko Beocanin

Complete Guide to Year 12 HSC Chemistry Module 6 - Acid/Base Reactions

One of the best online resources to learn Mod 6, written by Rishabh, Trisha, and qualified teachers.

Chemistry Team

Trisha Nangia & Rishabh Jain

How to Study for HSC Chemistry

Hi, I’m Catriona Shen, a HSC Chemistry tutor at Project Academy. Here is my guide on how to study for HSC Chemistry.

Catriona Shen

Senior HSC Chemistry Tutor, 99.75 ATAR

How I achieved a 99.60 ATAR and a State Rank in Economics

Like every other Year 12 student, I struggled A LOT with procrastination...

Jasmine De Rosa

99.60 ATAR, 6th in NSW for Economics

Maximise Your Chances Of Coming First At School

Trial any Project Academy course for 3 weeks.

NSW's Top 1% Tutors

Unlimited Tutorials

NSW's Most Effective Courses

Access to Project's iPad

Access to Exclusive Resources

Access to Project's Study Space

Select a year to see courses

Learn online or on-campus during the term or school holidays

OC Test Preparation

- Selective School Test Preparation

- Maths Acceleration

- English Advanced

- Maths Standard

- Maths Advanced

- Maths Extension 1

- English Standard

- Maths Extension 2

Get HSC exam ready in just a week

- UCAT Exam Preparation

Select a year to see available courses

- English Units 1/2

- Maths Methods Units 1/2

- Biology Units 1/2

- Chemistry Units 1/2

- Physics Units 1/2

- English Units 3/4

- Maths Methods Units 3/4

- Biology Unit 3/4

- Chemistry Unit 3/4

- Physics Unit 3/4

- UCAT Preparation Course

- Matrix Learning Methods

- Matrix Term Courses

- Matrix Holiday Courses

- Matrix+ Online Courses

- Campus overview

- Castle Hill

- Strathfield

- Sydney City

- Year 3 NAPLAN Guide

- OC Test Guide

- Selective Schools Guide

- NSW Primary School Rankings

- NSW High School Rankings

- NSW High Schools Guide

- ATAR & Scaling Guide

- HSC Study Planning Kit

- Student Success Secrets

- Reading List

- Year 6 English

- Year 7 & 8 English

- Year 9 English

- Year 10 English

- Year 11 English Standard

- Year 11 English Advanced

- Year 12 English Standard

- Year 12 English Advanced

- HSC English Skills

- How To Write An Essay

- How to Analyse Poetry

- English Techniques Toolkit

- Year 7 Maths

- Year 8 Maths

- Year 9 Maths

- Year 10 Maths

- Year 11 Maths Advanced

- Year 11 Maths Extension 1

- Year 12 Maths Standard 2

- Year 12 Maths Advanced

- Year 12 Maths Extension 1

- Year 12 Maths Extension 2

Science guides to help you get ahead

- Year 11 Biology

- Year 11 Chemistry

- Year 11 Physics

- Year 12 Biology

- Year 12 Chemistry

- Year 12 Physics

- Physics Practical Skills

- Periodic Table

- VIC School Rankings

- VCE English Study Guide

- Set Location

- 1300 008 008

- 1300 634 117

Welcome to Matrix Education

To ensure we are showing you the most relevant content, please select your location below.

Part 6: How To Write An Essay

Guide Chapters

- 1. How to Read and Analyse Texts

- 2. How to Research Your Texts

- 3. Understanding Assessments

- 4. How to Prepare for Assessments

- 5. How to Plan an Essay

- 6. How To Write An Essay

- 7. How to Edit Your Essay

- 8. How to Write Creatives

- 9. Imaginative Recreation

- 10. Multimodal Presentations

- 11. Short Answer Questions

- 12. How to analyse film

How to write an essay

In the last part of our Guide, we looked at how essays work and discussed the structure and planning of an essay . If you haven’t read it, you should go check that out first. In this part, we’ll get into the nitty-gritty of writing the essay and give you some tips for producing Band 6 responses in exam conditions.

But first, we need to discuss what essays are and how they should work.

In this article we discuss:

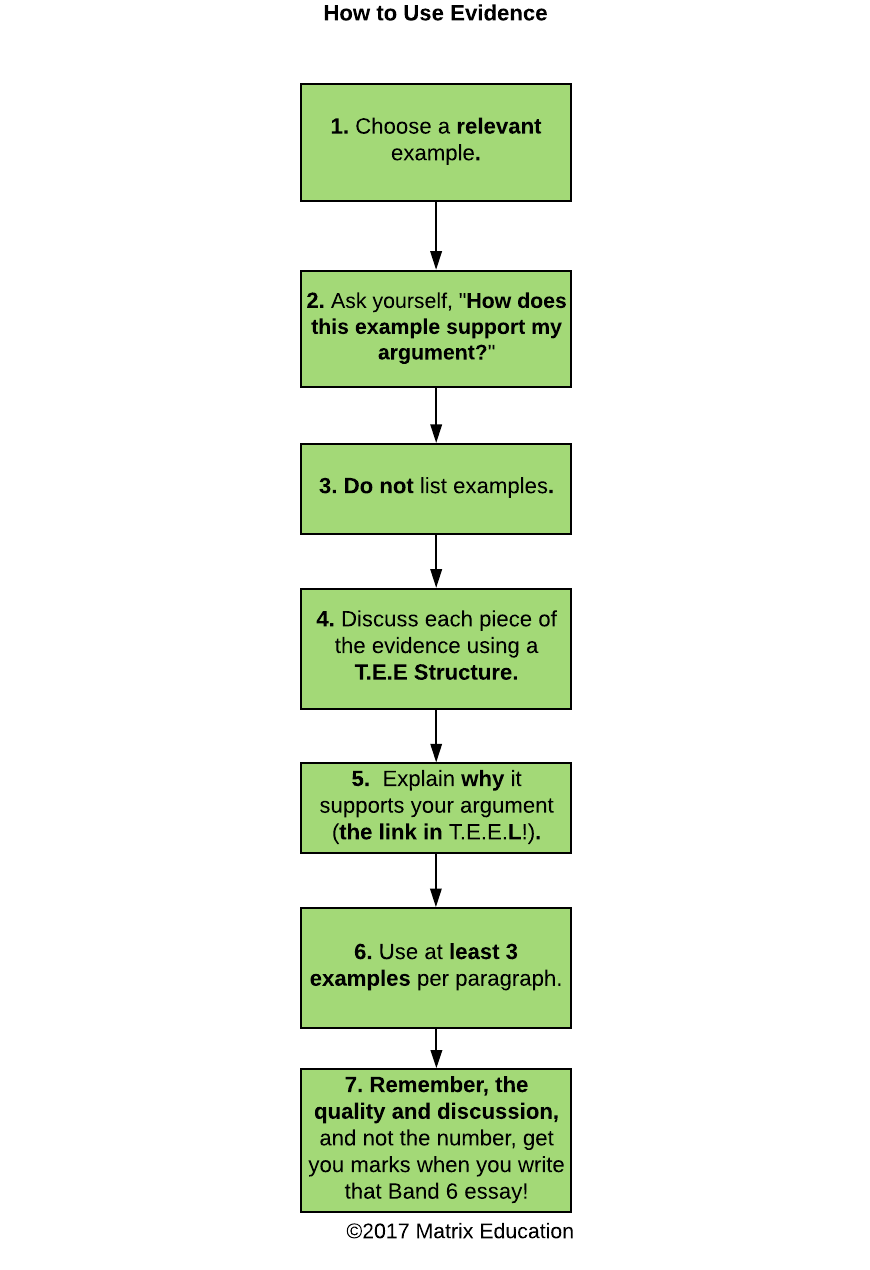

- How to Use Evidence

- Addressing the Module

- Discussing Supplementary Material

- Writing an Essay For an Exam

- How to Prepare for Essays in Exams

- How to Plan an Essay in an Exam

- How to Respond to Exam Essay Questions

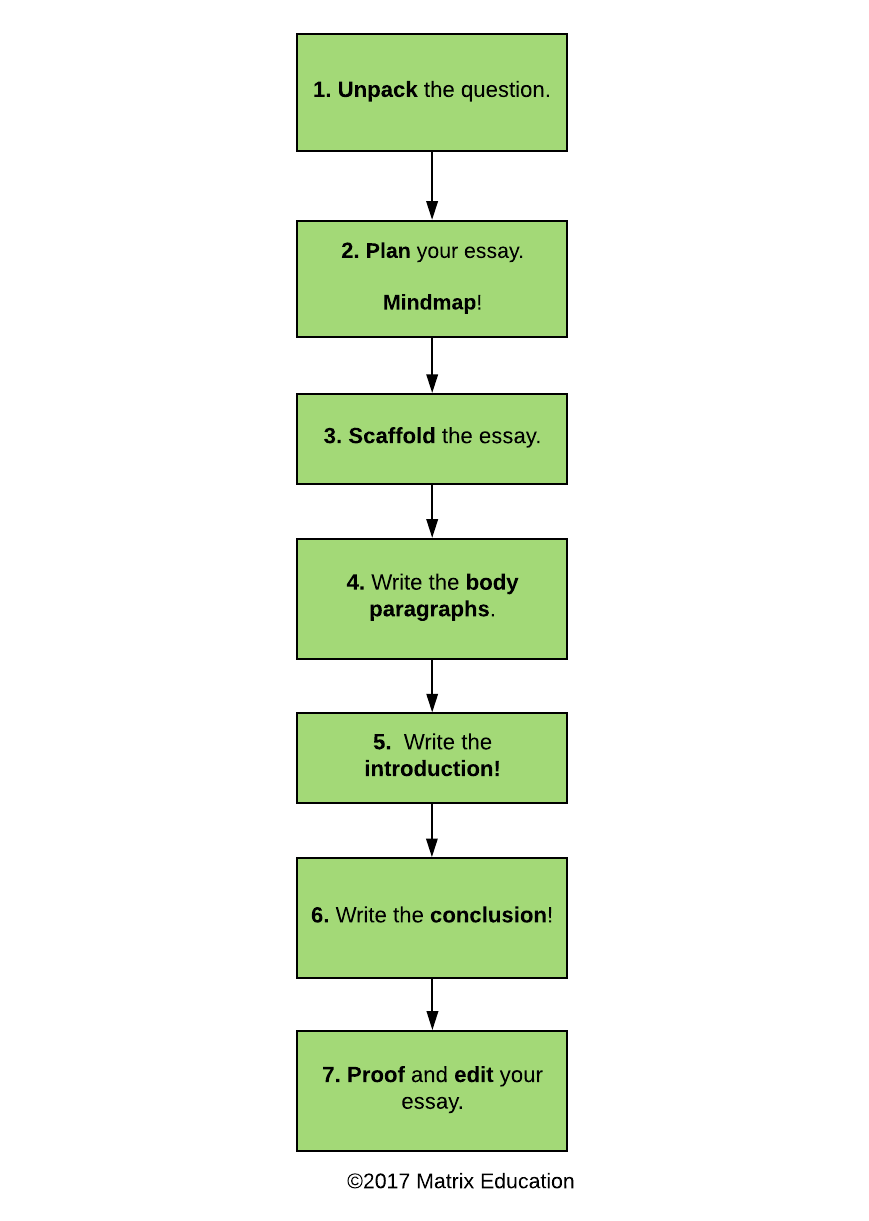

Just to recap this is the process we are using to write an essay:

Now that we’ve refreshed our memory, let’s pick up where we left off with the last post. Let’s put together our body paragraphs.

Writing the essay

Step 4: write the body paragraphs.

Now you are ready to start writing. You have your ideas, your thesis, and your examples. So, let’s start putting it together.

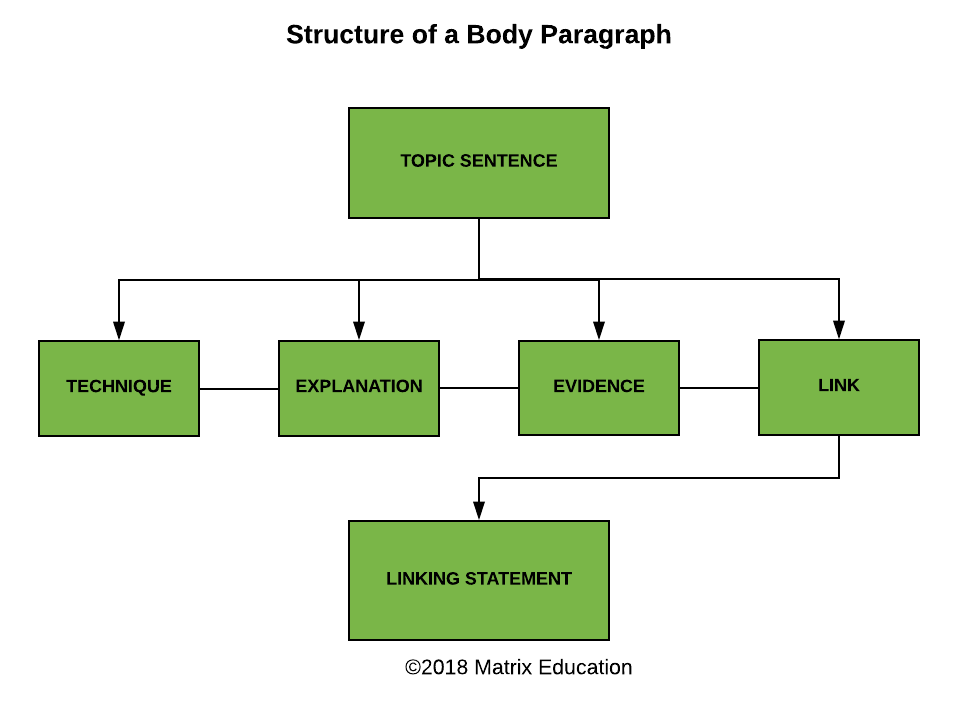

First, let’s think about the structure of a body paragraph. The following diagram visualises the structure of a body paragraph:

A body paragraph has 3 key components:

- The topic sentence – You use this to introduce the subject matter of the essay and locate it in the logic of your argument.

- Evidence and argument presented in a T.E.E.L structure – This is the substance of your argument.

- The linking statement – This connects your body paragraph to the rest of your essay at the same time as summing it up.

How do I write a Topic Sentence?

The topic sentence introduces your body paragraph. It must introduce the theme or idea for the paragraph and connect it to the broader argument in the essay. Thus, it is very important that you get it right. This can be daunting, but it shouldn’t be.

So, how do you write a good one? Let’s see:

- Check your plan and decide what the focus of the paragraph will be.

- Reread the question and your thesis in response to it.

- Ask yourself how you can combine these two parts – the focus of the paragraph and your thesis.

- Decide on how you can best convey this to a reader in one or two sentences.

- Write this down

Now you’ve got your topic sentence, you need to validate it by supporting it with evidence. So, where should you start with this?

In order to demonstrate how to write a body paragraph, let’s consider a student who is writing an essay on Arthur Miller’s The Crucible for Common Module: Texts and Human Experiences. We’ll look at their notes and then a paragraph they’ve produced, before walking you through how to use evidence. Let’s go!

The table below is a sample taken from their notes:

In their table, the student has broken down their examples by character, themes, technique, effect, and connection to the module. This is important for when students write T.E.E.L paragraphs. This allows them to easily transform their notes into part of an argument. For example, they have all the necessary information ready to incorporate into a T.E.E.L paragraph. Let’s see what that paragraph looks like:

This is a detailed paragraph, so how has the student gone from their notes to a complex response? Let’s see the steps that Matrix English Students are taught to follow when using evidence in a T.E.E.L structure.

How do I use evidence more effectively?

Evidence supports your arguments and demonstrates your logic to the reader. This means that your evidence must be relevant to your argument and be explained clearly. Using the following checklist will ensure this:

- Make sure your example is relevant to the question and thesis.

- Make sure that the evidence supports your topic sentence. Ask yourself, “how does this example support my argument?”

- Don’t list examples. Anybody can memorise a selection of examples and list them. You must produce an argument.

- Discuss the technique used in the example and the effect this has on meaning.

- Explain why the example supports your argument – this links it back to your topic sentence and thesis (the L part of a T.E.E.L Structure).

- Ensure that you use at least three examples per paragraph – this means using T.E.E.L three times at least per paragraph.

- Remember that it is the quality of the example and your discussion of it that will get you marks.

- Summarise your body paragraph in a linking statement – take your core idea and restate it. You may consider incorporating a connection to the module or reasserting your topic sentence .

Now, you’ve got your head around using evidence for the body paragraph, we should quickly discuss addressing the Module and using your supplementary material.

How do I address the module?

It is not enough to pay lip service to the Module in the introduction and conclusion, you need to discuss it in a sustained manner throughout your response. To do this, you must:

- Incorporate the Module concerns into your topic and linking sentences – Don’t merely make the topic sentences about a theme or the text. Connect them to the module by incorporating the language of the Module Rubric.

- Connect your examples to the Module concerns – for example, in a Module A essay when discussing evidence, explain how it conveys context or demonstrates the importance of storytelling.

- Discuss the module with your evidence – You must connect your examples to the module concerns. For example, if you are studying a text for Module B then you must explain how your examples demonstrate the presence (or absence) of Textual Integrity, lasting value, or universal human appeal.

How do I discuss supplementary material?

Module B for Year 11s and 12 and Extension English require students to consider the perspectives of others in their writing. Some assessment tasks for other units might require students to read a critical interpretation of their text and discuss it in relation to their own perspective of the text. When doing this, there are some important rules to remember:

- Don’t let critics overshadow your perspective – Don’t begin a paragraph with somebody else’s perspective. Begin with your interpretation of the text and then compare theirs with your own.

- Don’t use overly long quotations – You want to use short and direct quotations from others so as to not drown out your own voice.

- Explain the relevance of the critic – Don’t just quote critics, explain in detail why you disagree or agree with them. Whenever possible, use an example to support your position. This will ensure that the essay remains about your insights and perspective on the text and module.

Using supplementary material and critical perspectives in essays, especially during exams, is a skill. Matrix students get detailed explanations of how to do this in the Matrix Theory books. The best way to perfect your use of critical perspectives is to write practice essays incorporating them and seeking feedback on your efforts.

If you would like a more detailed explanation of writing body paragraphs, read our posts:

- Essay Writing Part 3: How to Write a Topic Sentence

- Essay Writing Part 4: How to Write A Body Paragraph .

Now that we’ve got our body paragraphs down we need to look at how to write introductions and conclusions.

Step 5: Write the introduction

Introductions and conclusions are very important because they are the first and last words that your marker read. First impressions and final impressions matter, so it is very important to get them right! So, we need to know what an introduction needs to do.

An essay introduction must do a few different things:

- It must present your thesis and answer the question

- Present the ideas that support your argument

- Address the module you are studying

- Signpost and foreshadow your topic sentences

Don’t worry, it may sound like a lot, but it isn’t really. Let’s have a look at some of the practical steps that Year 11 Matrix English students learn in class.

A good approach is to break the four purposes of an introduction into a series of questions you should ask yourself:

- Introduce your argument (the thesis). – What do you feel is the correct answer to the question?

- Present the ideas you feel are relevant to your argument. – What have you studied that supports this position?

- Explain how you will discuss them. – How will you logically structure your argument?

- Explain the connection to the module. – How does all of this connect to the module?

Initially, it may be easier for you to write your body paragraphs first and then use them to produce your first introduction. This is because:

- You already have your thesis – You just need to polish the wording of it.

- You know what your themes are – You can use your topic sentences to produce your thematic framework.

- You have discussed the module concerns throughout the essay – You just have to summarise the relevance into one sentence.

If you would like more information on writing introductions, you should read our detailed blog posts:

- Essay Writing Part 1: How to Write a Thesis Statement

- Essay Writing Part 2: How to Structure Your Essay Introduction .

Step 6: Write the conclusion

Remember, your conclusion needs to recap your ideas and thesis. You also need to leave a lasting impression on your reader. Conclusion are actually the easiest part of the essay to write.

So, what does writing a conclusion involve? Let’s take a look:

- Reassert your argument (the thesis).

- Recap your supporting ideas and the approach you took to them (thematic framework).

- Make a final statement about your argument and the module.

You should only write your conclusion after you have produced the rest of your essay. Often the hardest part is knowing how to finish the conclusion.

The thesis (1.) and thematic framework (2.) need only be reworded from the introduction, but your concluding statement (3.) needs to do something new. The final statement needs to explain the connection of your argument to the module and what YOU have taken away from the study of the module.

It is worthwhile being succinct and honest about your experience of studying the unit, rather than making a hyperbolic statement about human experience (sometimes known as a “pop-outro”). To give you a sense of what this means, consider these Module A concluding statements:

- Don’t write : “ The Crucible illustrates how human beings will turn on each other at a moments notice when threatened with tyranny and death!”

- Do write : “My study of Miller’s The Crucible has informed how composers will try and use art to represent and comment on important moments in human culture and history.”

The first statement tells the marker nothing about what the student has taken learned from the module. The statement it makes only partially relates to the module, and it is not original – many students will write something similar.

The second statement gives a personal insight into the student’s experience of reading The Crucible and studying Module A: Narratives that Shaped the World. This second statement is what your markers are looking for!

The best way to get good at writing introductions and conclusions is to practice writing them to a variety of questions. You don’t always have to write the whole essay, but you can (it’s the best practice for writing Band 6 essays)!

If you are still struggling with how to write your conclusion, take the time to read through our detailed blog post Essay Writing Part 5: How to Write a Conclusion .

You can find all of those essay writing blog posts here:

- Essay Writing Part 2: How to Structure Your Essay Introduction

- Essay Writing Part 4: How to Write A Body Paragraph

- Essay Writing Part 5: How to Write a Conclusion

Now that we’ve looked at the basics of how to write an essay, we need to consider the exam essay. It’s one thing to take your time crafting an essay over a couple of hours or days, but an entirely different experience to write one in under 40 minutes. It’s now time to see what that involves and how it differs from the process above.

Back to Top

Writing an essay for an exam

The most common form of assessment for Stage 6 English is the in-class essay or HSC essay. (You will have to sit at least 6 essays in Year 12!) Let’s have a look at some stratagems for preparing for these assessments.

What are markers looking for?

Markers must assess the following criteria:

- Knowledge of the text

- Understanding of the module

- Understanding of the question

- Ability to structure an argument

- Ability to use evidence

- Usage of written English

- Ability to provide an insight into your perspective of the text

It is imperative that you keep these aims in mind at all times when you are writing your essay. Matrix students are taught how to address these criteria in their responses. You must ensure that you demonstrate a skilful ability to answer each of the seven criteria above.

Want to ace English, faster?

Learn with HSC experts at your convenience to save time and get ahead before your HSC. Learn more !

Start HSC English confidently

Expert teachers, detailed feedback, one-to-one help! Learn from home with Matrix+ Online English courses.

How to prepare for essays in exams

It’s tempting to memorise an essay for an exam. Don’t. It’s a risky strategy and assessors are increasingly asking more complex and specific questions to catch out students who try and game the system like this. This is especially true in the HSC, where the questions are becoming more focused and thematically specific to weed out students who engage in this practice.

Instead, you want to study your texts in a holistic manner that allows you to respond to a wide range of questions. Let’s have a look at some of the tips that Matrix students receive:

- Know Your Texts – Make sure you read your texts multiple times!

- Know Your Module – Make sure that you are very familiar with the syllabus rubrics and outlines.

- Organise Your Notes – Make use of tables to organise and sort your notes.

- Make a Study Rhythm – You know when you have assessments coming up well in advance. Plan out your study timetable long before you receive your notification so that you have already begun studying for your task. Do not wait until two weeks before your exam to begin studying!

- Make a Study Group – Share your notes with your peers. Take turns quizzing each other on content.

- Write Lots of Practice Essays – The best way to improve your essay writing skills is to write practice essays to as many different questions as you can. Ask your teacher for practice questions. Matrix Theory Books contain a variety of Module specific practice questions.

- Get Feedback – Seek out feedback on your essays. Ask your teacher, your parents, and those in your study group. Feedback is a great way to get a second opinion on your work and argument.

- Write More Practice Essays – There is no such thing as too many practice essays. The more you write and refine your essay writing and structure, the better you will be as an essayist.

This is what to do to prepare, but what do you do during the exam? Let’s see.

How to plan an essay in an exam

Gameday has arrived. You sit in the classroom and wait for your teacher to say: “You may open your paper!” But what do you do after that?

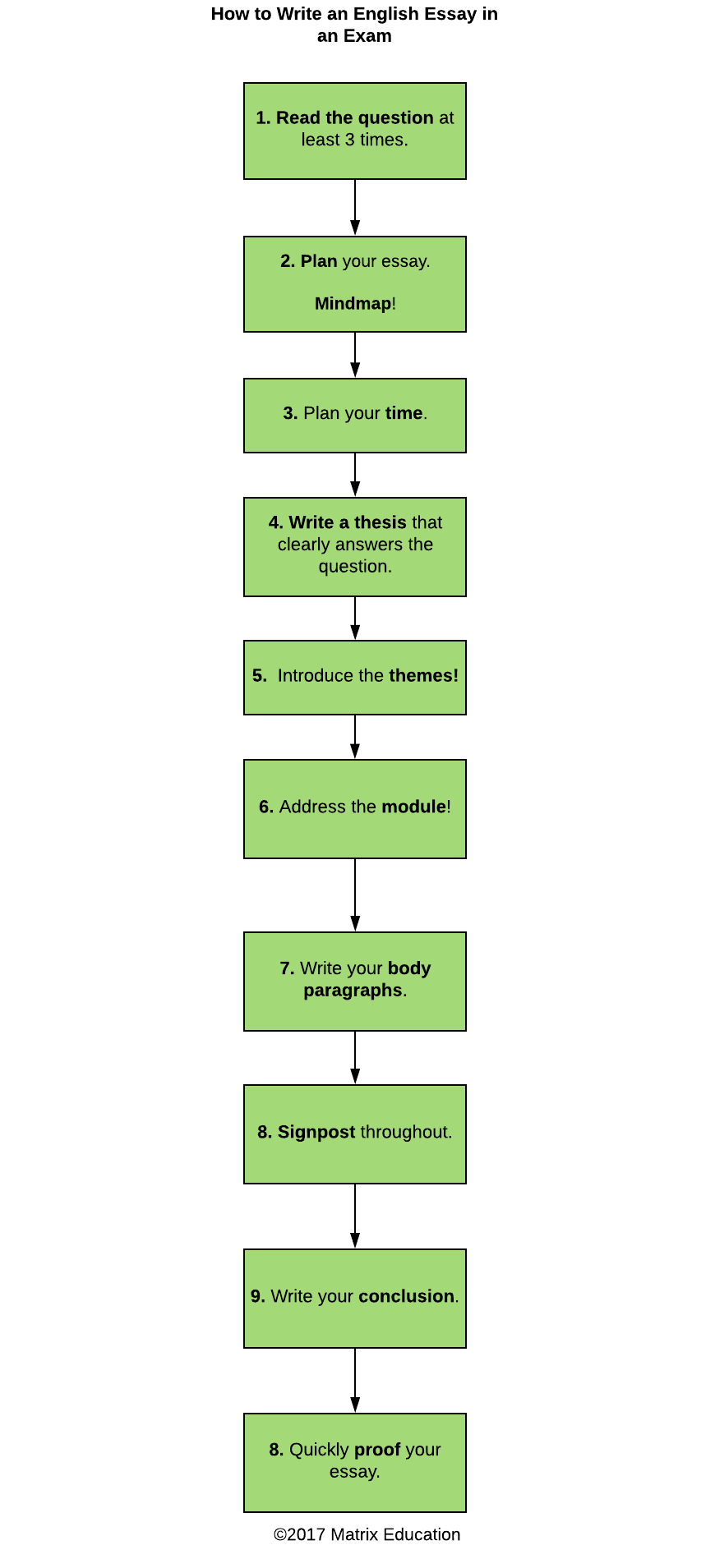

Here is a step-by-step guide:

- Read the question(s) at least 3 times. You want to be certain about what it is asking you.

- Sometimes you won’t be able to plan your essay on paper for a few minutes, but you can still do it in your head. Unpack the question and think about what your response to it is. Mentally map out the most relevant themes and best structure. Consider what examples are best suited to supporting your argument. Take the time to plot these things out when they say you can start writing. It is worth the extra few minutes to have a plan on paper to guide your response.

- Sometimes you will be able to plan before you write. Take advantage of this and do a thorough mind-map. Plot out your themes, structure, and examples. Try to sketch out your topic sentences and thesis. The more you can set down before you are told to start your essay, the more your essay will have detail, structure, and insight.

- Plan your time! Set a time limit per section and stick to it. You don’t want to have to skip a paragraph or run out of time to finish the conclusion. If you must choose, finish your conclusion over a body paragraph.

- Write a thesis that answers the question. It’s essential that you present a clear, direct, and concise response to the question.

- Provide a thorough thematic framework. The more detailed your framing of your argument, the easier it is for your marker to follow your argument and logic. You want to make their job easy. It makes it easier for them to give you marks.

- Make sure you relate the introduction to the Module.

- When you write your body paragraphs, always refer back to your mind-map and your introduction. You need to write a sustained argument under pressure. It is easy to get side-tracked and go off on tangents. Referring to your plans will keep you focused and on track.

- Make sure you signpost! Topic Sentences and Linking Statements guide your marker through your essay.

- Make sure that you sum up your argument clearly and accurately. If possible read through your essay before writing the conclusion. This way you can ensure that you are writing the best conclusion for your argument!

- Proof your essay. You want to mop up those little errors that may cost you marks!

How to respond to exam essay questions

One of the most difficult parts of dealing with exams is responding to what the questions ask of you. Exams are stressful, and dealing with a potentially unknown quantity can add to the anxiety. But there are some strategies to take the sting out of this. Let’s see what they are:

- Familiarise yourself with the module rubric and assessment notification – Your teachers will not set you a question that is completely unexpected. They must draw the ideas and terms of the question from the Stage 6 Preliminary English Module rubrics that we looked at previously in Part 1 . Knowing the details of these rubrics will enable you to unpack the question’s module concerns with relative ease and focus on the textual aspects of the question.

- Know your text – The easiest way to fail an essay is to not know your text well. Make sure that you have studied it in depth and revised all of the themes that you can discern. If you’re unsure, read Textual Analysis – How to Analyse Your English Texts for Evidence .

- Answer the question, don’t repeat or paraphrase it – Your markers are looking to assess your understanding of the text and module. They are specifically looking for your insights into them. To achieve this you need to respond to the question rather than reiterate or restate it. Make sure you answer the question, “What does this mean?”

Let’s have a look at an example question for Module A – Narratives that Shaped the World .

This question is drawing on the language of the module. The relevant key phrases from the module are :

- “Students explore a range of narratives from the past and the contemporary era that illuminate and convey ideas, attitudes and values.”

- “They consider the powerful role of stories and storytelling as a feature of narrative in past and present societies, as a way of… connecting people within and across … historical eras; inspiring change or consolidating stability.”

- “Students deepen their understanding of how narrative shapes meaning in a range of modes, media and forms, and how it influences the way that individuals and communities understand and represent themselves.”

- “Students analyse and evaluate … texts to explore how narratives are shaped by the context and values of composers … responders alike.”

- “They may investigate how narratives can be appropriated, reimagined or reconceptualised for new audiences.”

To answer this question, you will need to address these aspects of the module.

One way of interpreting this statement is that:

- It is arguing that humans develop their identity, in part, through storytelling.

- We develop our understanding of the world through the texts that we read and engage with.

- We define our cultural and personal identities, in part, through the texts we read and write.

- We also try to understand and criticise contemporary events by discussing them through the lens of past events and narratives.

Now we need to develop this into a thesis statement by combining these concepts into a couple of sentences that answer the question and discuss The Crucible . That could look like this:

“Storytelling allows composers to consider and criticise contemporary events for audiences by appropriating narratives from human history. Miller compels audiences to experience oppression through his dramatic interrogation of the growing tyranny of McCarthyism in the 1950s as he reimagines the historical narrative of the Salem Witch Trials.”

Once you’ve written an essay, you will need to edit it. In the next post, we’ll have a look at how to proof and edit your work in detail.

Part 7: How to Edit Your Essay

© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Related courses

Year 3 english.

Year 3 English tutoring at Matrix will help your child improve their reading and writing skills.

Learning methods available

Year 3 Maths

Year 3 Maths tutoring at Matrix will help your child improve their maths skills and confidence.

Year 4 English

Year 4 English tutoring at Matrix will help your child improve their reading and writing skills.

Year 4 Maths

Year 4 Maths tutoring at Matrix will help your child improve their maths skills and confidence.

Sydney's best OC prep tutoring by experienced teachers and tried, tested resources. Learn online or on-campus. Try free now.

Year 5 Maths

Year 5 Maths tutoring at Matrix will help your child improve their maths skills and confidence.

More essential guides

The Beginner’s Guide to ATAR & Scaling

The Beginner's Guide to UCAT

High School Survival Guides

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Whether you’re writing a detailed persuasive essay for Module B or a discursive piece for a Module C assessment, your ideas and opinions are crucial. The difference is how you present them. When you write a persuasive essay, there is the assumption that it is your voice and your opinion.

Discursive: We’ll be diving into what exactly this style of writing entails in this guide! Persuasive: This writing style aims for you to convince the reader of a particular argument or idea.

The first step is to find a topic which you don’t particularly care about (so you aren’t tempted to push a particular opinion/side - it’s not a persuasive essay), but a topic that is interesting enough to write about.

13 min read. ·. Jul 10, 2024. Achieving a Band 6 in HSC English is more than just a milestone; it’s a testament to your analytical prowess, writing flair, and intellectual commitment.

In this part, we’ll get into the nitty-gritty of writing the essay and give you some tips for producing Band 6 responses in exam conditions. But first, we need to discuss what essays are and how they should work. In this article we discuss: How to Use Evidence. Addressing the Module. Discussing Supplementary Material. Writing an Essay For an Exam.

Step 1: Understanding what makes a Band 6 HSC English Essay & Planning. HSC Bands — what do they mean? Bands are how your HSC exams will be graded — instead of receiving a B+ or a mark out of 100, your exam results will be placed in a specific band.