We have emailed you a PDF version of the article you requested.

Can't find the email?

Please check your spam or junk folder

You can also add [email protected] to your safe senders list to ensure you never miss a message from us.

Universe 25: The Mouse "Utopia" Experiment That Turned Into An Apocalypse

Complete the form below and we will email you a PDF version

Cancel and go back

IFLScience needs the contact information you provide to us to contact you about our products and services. You may unsubscribe from these communications at any time.

For information on how to unsubscribe, as well as our privacy practices and commitment to protecting your privacy, check out our Privacy Policy

Complete the form below to listen to the audio version of this article

Advertisement

Subscribe today for our Weekly Newsletter in your inbox!

James Felton

Senior Staff Writer

James is a published author with four pop-history and science books to his name. He specializes in history, strange science, and anything out of the ordinary.

Book View full profile

Book Read IFLScience Editorial Policy

DOWNLOAD PDF VERSION

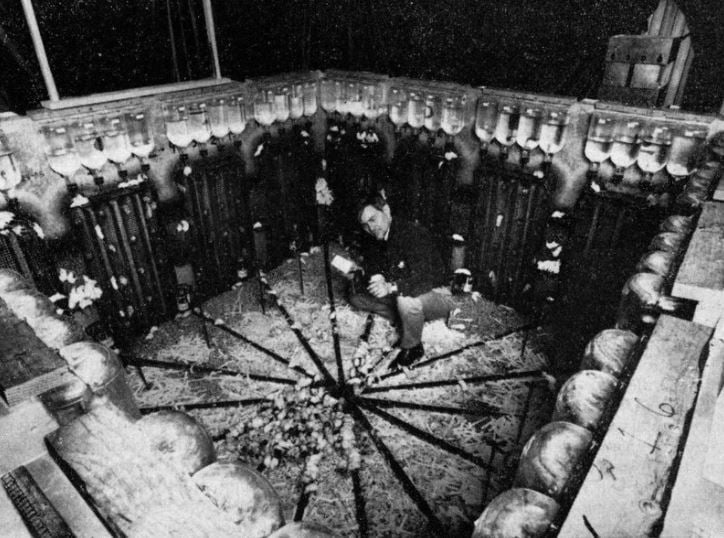

The utopia in all its glory. Image credit: Yoichi R Okamoto, White House photographer (public domain, via Wikimedia Commons ).

Over the last few hundred years, the human population of Earth has seen an increase, taking us from an estimated one billion in 1804 to seven billion in 2017. Throughout this time, concerns have been raised that our numbers may outgrow our ability to produce food, leading to widespread famine.

Some – the Malthusians – even took the view that as resources ran out, the population would "control" itself through mass deaths until a sustainable population was reached. As it happens, advances in farming, changes in farming practices, and new farming technology have given us enough food to feed 10 billion people , and it's how the food is distributed which has caused mass famines and starvation. As we use our resources and the climate crisis worsens, this could all change – but for now, we have always been able to produce more food than we need, even if we have lacked the will or ability to distribute it to those that need it.

But while everyone was worried about a lack of resources, one behavioral researcher in the 1970s sought to answer a different question: what happens to society if all our appetites are catered for, and all our needs are met? The answer – according to his study – was an awful lot of cannibalism shortly followed by an apocalypse.

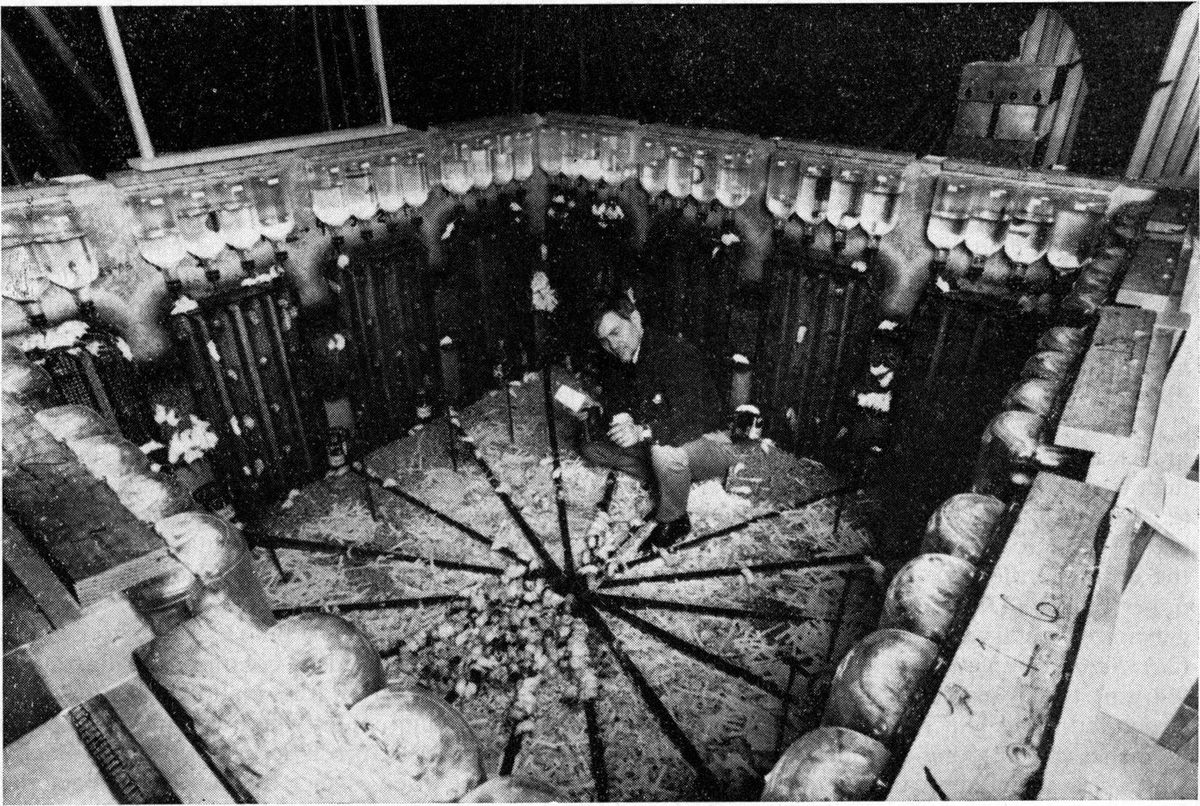

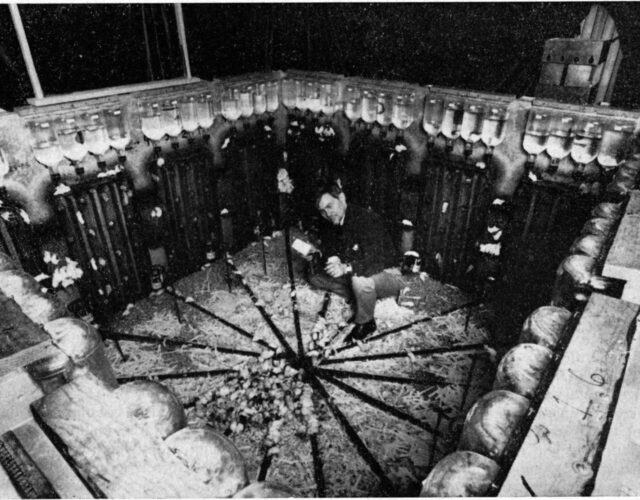

John B Calhoun set about creating a series of experiments that would essentially cater to every need of rodents, and then track the effect on the population over time. The most infamous of the experiments was named, quite dramatically, Universe 25 .

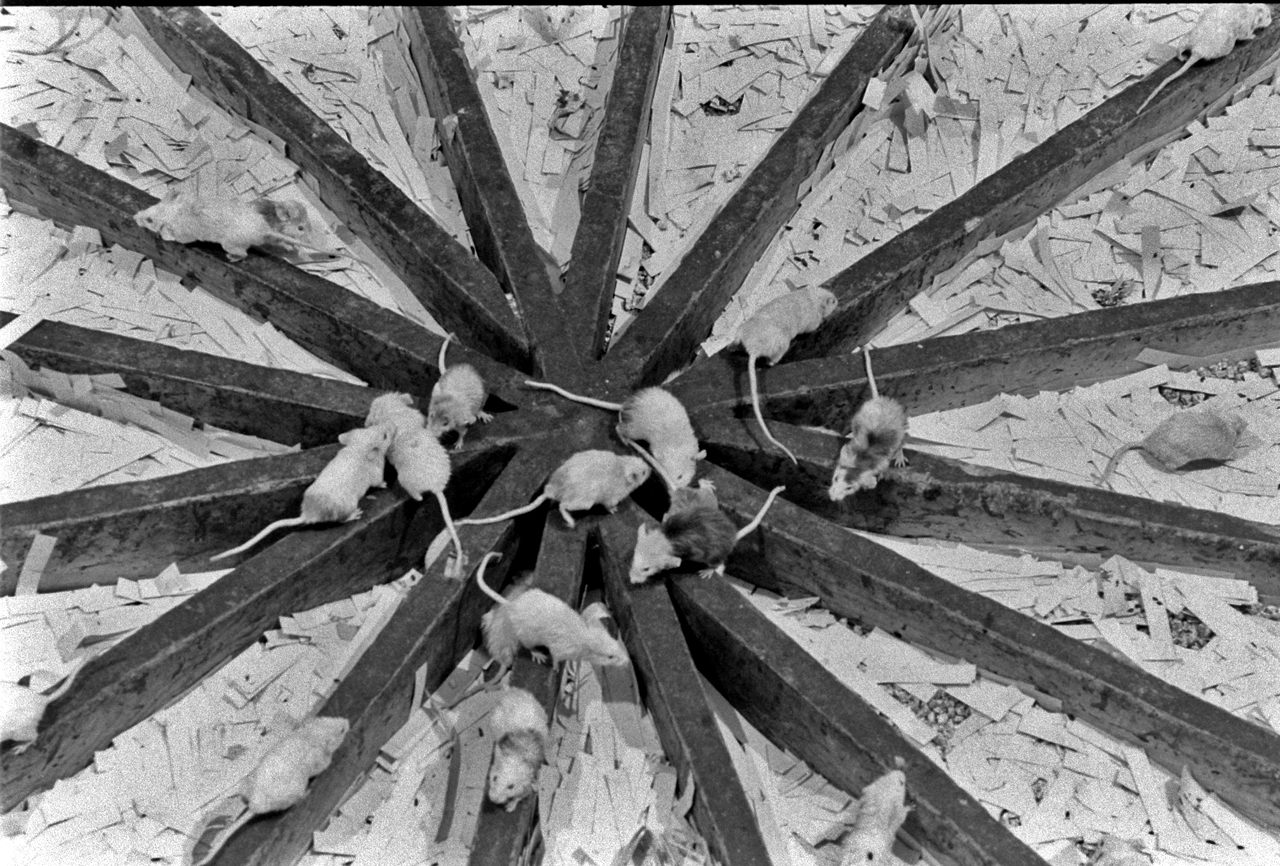

In this study, he took four breeding pairs of mice and placed them inside a "utopia". The environment was designed to eliminate problems that would lead to mortality in the wild. They could access limitless food via 16 food hoppers, accessed via tunnels, which would feed up to 25 mice at a time, as well as water bottles just above. Nesting material was provided. The weather was kept at 68°F (20°C), which for those of you who aren't mice is the perfect mouse temperature. The mice were chosen for their health, obtained from the National Institutes of Health breeding colony. Extreme precautions were taken to stop any disease from entering the universe.

As well as this, no predators were present in the utopia, which sort of stands to reason. It's not often something is described as a "utopia, but also there were lions there picking us all off one by one".

The experiment began, and as you'd expect, the mice used the time that would usually be wasted in foraging for food and shelter for having excessive amounts of sexual intercourse. About every 55 days, the population doubled as the mice filled the most desirable space within the pen, where access to the food tunnels was of ease.

When the population hit 620, that slowed to doubling around every 145 days, as the mouse society began to hit problems. The mice split off into groups, and those that could not find a role in these groups found themselves with nowhere to go.

"In the normal course of events in a natural ecological setting somewhat more young survive to maturity than are necessary to replace their dying or senescent established associates," Calhoun wrote in 1972 . "The excess that find no social niches emigrate."

Here, the "excess" could not emigrate, for there was nowhere else to go. The mice that found themself with no social role to fill – there are only so many head mouse roles, and the utopia was in no need of a Ratatouille -esque chef – became isolated.

"Males who failed withdrew physically and psychologically; they became very inactive and aggregated in large pools near the center of the floor of the universe. From this point on they no longer initiated interaction with their established associates, nor did their behavior elicit attack by territorial males," read the paper. "Even so, they became characterized by many wounds and much scar tissue as a result of attacks by other withdrawn males."

The withdrawn males would not respond during attacks, lying there immobile. Later on, they would attack others in the same pattern. The female counterparts of these isolated males withdrew as well. Some mice spent their days preening themselves, shunning mating, and never engaging in fighting. Due to this they had excellent fur coats, and were dubbed, somewhat disconcertingly, the "beautiful ones".

The breakdown of usual mouse behavior wasn't just limited to the outsiders. The "alpha male" mice became extremely aggressive, attacking others with no motivation or gain for themselves, and regularly raped both males and females . Violent encounters sometimes ended in mouse-on-mouse cannibalism.

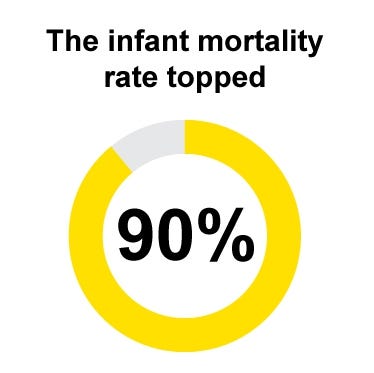

Despite – or perhaps because – their every need was being catered for, mothers would abandon their young or merely just forget about them entirely, leaving them to fend for themselves. The mother mice also became aggressive towards trespassers to their nests, with males that would normally fill this role banished to other parts of the utopia. This aggression spilled over, and the mothers would regularly kill their young. Infant mortality in some territories of the utopia reached 90 percent.

This was all during the first phase of the downfall of the "utopia". In the phase Calhoun termed the "second death", whatever young mice survived the attacks from their mothers and others would grow up around these unusual mouse behaviors. As a result, they never learned usual mice behaviors and many showed little or no interest in mating, preferring to eat and preen themselves, alone.

The population peaked at 2,200 – short of the actual 3,000-mouse capacity of the "universe" – and from there came the decline. Many of the mice weren't interested in breeding and retired to the upper decks of the enclosure, while the others formed into violent gangs below, which would regularly attack and cannibalize other groups as well as their own. The low birth rate and high infant mortality combined with the violence, and soon the entire colony was extinct . During the mousepocalypse, food remained ample, and their every need completely met.

Calhoun termed what he saw as the cause of the collapse "behavioral sink".

"For an animal so simple as a mouse, the most complex behaviors involve the interrelated set of courtship, maternal care, territorial defence and hierarchical intragroup and intergroup social organization," he concluded in his study.

"When behaviors related to these functions fail to mature, there is no development of social organization and no reproduction. As in the case of my study reported above, all members of the population will age and eventually die. The species will die out."

He believed that the mouse experiment may also apply to humans, and warned of a day where – god forbid – all our needs are met.

"For an animal so complex as man, there is no logical reason why a comparable sequence of events should not also lead to species extinction. If opportunities for role fulfilment fall far short of the demand by those capable of filling roles, and having expectancies to do so, only violence and disruption of social organization can follow."

At the time, the experiment and conclusion became quite popular, resonating with people's feelings about overcrowding in urban areas leading to "moral decay" (though of course, this ignores so many factors such as poverty and prejudice).

However, in recent times, people have questioned whether the experiment could really be applied so simply to humans – and whether it really showed what we believed it did in the first place.

The end of the mouse utopia could have arisen "not from density, but from excessive social interaction," medical historian Edmund Ramsden said in 2008 . “Not all of Calhoun’s rats had gone berserk. Those who managed to control space led relatively normal lives.”

As well as this, the experiment design has been criticized for creating not an overpopulation problem, but rather a scenario where the more aggressive mice were able to control the territory and isolate everyone else. Much like with food production in the real world, it's possible that the problem wasn't of adequate resources, but how those resources are controlled.

THIS WEEK IN IFLSCIENCE

Article posted in.

overpopulation,

weird and wonderful

More Nature Stories

link to article

Soaring Birds, Buzzing Bugs – Art And Science Capture The “Hidden Beauty” Of Flight

Just How Many “Gates To Hell” Are There On Earth?

A "Giant Mercury Bomb" Threatens To Go Off In North America's Arctic

Earth Sausage, Pompeii Panic, And The Disco Planet

Legends Of The Bondo Apes: Are They Giant Ferocious Lion Killers?

Space Archaeology, Titanium Hearts, And The Russian Sleep Experiment

This Old Experiment With Mice Led to Bleak Predictions for Humanity’s Future

From the 1950s to the 1970s, researcher John Calhoun gave rodents unlimited food and studied their behavior in overcrowded conditions

Maris Fessenden ; Updated by Rudy Molinek

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7c/36/7c36a5fc-01a8-4877-aeb4-ad87704efcf2/calhounj.jpg)

What does utopia look like for mice and rats? According to a researcher who did most of his work in the 1950s through 1970s, it might include limitless food, multiple levels and secluded little condos. These were all part of John Calhoun’s experiments to study the effects of population density on behavior. But what looked like rodent paradises at first quickly spiraled into out-of-control overcrowding, eventual population collapse and seemingly sinister behavior patterns.

In other words, the mice were not nice.

Working with rats between 1958 and 1962, and with mice from 1968 to 1972, Calhoun set up experimental rodent enclosures at the National Institute of Mental Health’s Laboratory of Psychology. He hoped to learn more about how humans might behave in a crowded future. His first 24 attempts ended early due to constraints on laboratory space. But his 25th attempt at a utopian habitat, which began in 1968, would become a landmark psychological study. According to Gizmodo ’s Esther Inglis-Arkell, Calhoun’s “Universe 25” started when the researcher dropped four female and four male mice into the enclosure.

By the 560th day, the population peaked with over 2,200 individuals scurrying around, waiting for food and sometimes erupting into open brawls. These mice spent most of their time in the presence of hundreds of other mice. When they became adults, those mice that managed to produce offspring were so stressed out that parenting became an afterthought.

“Few females carried pregnancies to term, and the ones that did seemed to simply forget about their babies,” wrote Inglis-Arkell in 2015. “They’d move half their litter away from danger and forget the rest. Sometimes they’d drop and abandon a baby while they were carrying it.”

A select group of mice, which Calhoun called “the beautiful ones,” secluded themselves in protected places with a guard posted at the entry. They didn’t seek out mates or fight with other mice, wrote Will Wiles in Cabinet magazine in 2011, “they just ate, slept and groomed, wrapped in narcissistic introspection.”

Eventually, several factors combined to doom the experiment. The beautiful ones’ chaste behavior lowered the birth rate. Meanwhile, out in the overcrowded common areas, the few remaining parents’ neglect increased infant mortality. These factors sent the mice society over a demographic cliff. Just over a month after population peaked, around day 600, according to Distillations magazine ’s Sam Kean, no baby mice were surviving more than a few days. The society plummeted toward extinction as the remaining adult mice were just “hiding like hermits or grooming all day” before dying out, writes Kean.

Calhoun launched his experiments with the intent of translating his findings to human behavior. Ideas of a dangerously overcrowded human population were popularized by Thomas Malthus at the end of the 18th century with his book An Essay on the Principle of Population . Malthus theorized that populations would expand far faster than food production, leading to poverty and societal decline. Then, in 1968, the same year Calhoun set his ill-fated utopia in motion, Stanford University entomologist Paul Ehrlich published The Population Bomb . The book sparked widespread fears of an overcrowded and dystopic imminent future, beginning with the line, “The battle to feed all of humanity is over.”

Ehrlich suggested that the impending collapse mirrored the conditions Calhoun would find in his experiments. The cause, wrote Charles C. Mann for Smithsonian magazine in 2018, would be “too many people, packed into too-tight spaces, taking too much from the earth. Unless humanity cut down its numbers—soon—all of us would face ‘mass starvation’ on ‘a dying planet.’”

Calhoun’s experiments were interpreted at the time as evidence of what could happen in an overpopulated world. The unusual behaviors he observed—such as open violence, a lack of interest in sex and poor pup-rearing—he dubbed “behavioral sinks.”

After Calhoun wrote about his findings in a 1962 issue of Scientific American , that term caught on in popular culture, according to a paper published in the Journal of Social History . The work tapped into the era’s feeling of dread that crowded urban areas heralded the risk of moral decay.

Events like the murder of Kitty Genovese in 1964—in which false reports claimed 37 witnesses stood by and did nothing as Genovese was stabbed repeatedly—only served to intensify the worry. Despite the misinformation, media discussed the case widely as emblematic of rampant urban moral decay. A host of science fiction works—films like Soylent Green , comics like 2000 AD —played on Calhoun’s ideas and those of his contemporaries . For example, Soylent Green ’s vision of a dystopic future was set in a world maligned by pollution, poverty and overpopulation.

Now, interpretations of Calhoun’s work have changed. Inglis-Arkell explains that the main problem of the habitats he created wasn’t really a lack of space. Rather, it seems likely that Universe 25’s design enabled aggressive mice to stake out prime territory and guard the pens for a limited number of mice, leading to overcrowding in the rest of the world.

However we interpret Calhoun’s experiments, though, we can take comfort in the fact that humans are not rodents. Follow-up experiments by other researchers, which looked at human subjects, found that crowded conditions didn’t necessarily lead to negative outcomes like stress, aggression or discomfort.

“Rats may suffer from crowding,” medical historian Edmund Ramsden told the NIH Record ’s Carla Garnett in 2008, “human beings can cope.”

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Maris Fessenden | | READ MORE

Maris Fessenden is a freelance science writer and artist who appreciates small things and wide open spaces.

Rudy Molinek | READ MORE

Rudy Molinek is Smithsonian magazine's 2024 AAAS Mass Media Fellow.

MASONIC PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY

Seeking to recapture the spirit of the renaissance..

Masonic Philosophical Society

The Rat Utopia Experiments That Predicted Humanity’s Dark Future

Global population estimates exceeded 8 billion people in November 2022. That’s more people than have ever existed! In fact, a jaw-dropping 7pc of people who have ever lived are alive today. Surely, such a startling statistic should be front-page news. Yet it was hardly a blip. The soaring trajectory of human population growth over the past two centuries is now an accepted fact – an ascending rollercoaster without any sense of down.

That wasn’t always so. In the mid-twentieth century, the rampant population growth worried many who feared imminent overcrowding, overpopulation, and societal collapse. Short stories like Billennuim warned of a world of box-like apartments and pedestrian congestion lasting days, where every inch of land is devoted to housing or farming. Known as the neo-Malthusians (after 18 th -century scholar Thomas Malthus), they predicted a terrifying future if the rollercoaster of human population growth rose ever higher; they dared to look down.

Ethologist John Calhoun’s Rat Utopia experiments fueled these fears, pointing towards a spiraling degradation of normal social interactions. He coined the term “behavioral sink” to describe the so-called aberrant behaviors resulting from overcrowded population densities. It was the stuff of nightmares – at least to the nervous 1970s audience.

In the mid-twentieth century, the rampant population growth worried many who feared imminent overcrowding, overpopulation, and societal collapse.

Calhoun’s early experiments involved a 28-month study of a colony of Norway rats in a 10,000-square-foot outdoor pen. Beginning with five females, he predicted an exponential population rise leading to a theoretical 5,000 healthy progeny by the experiment’s end. In fact, the population never exceeded 200 individuals, stabilizing at 150. Surprisingly, the rats congregated in groups of roughly a dozen – the rat’s social limit.

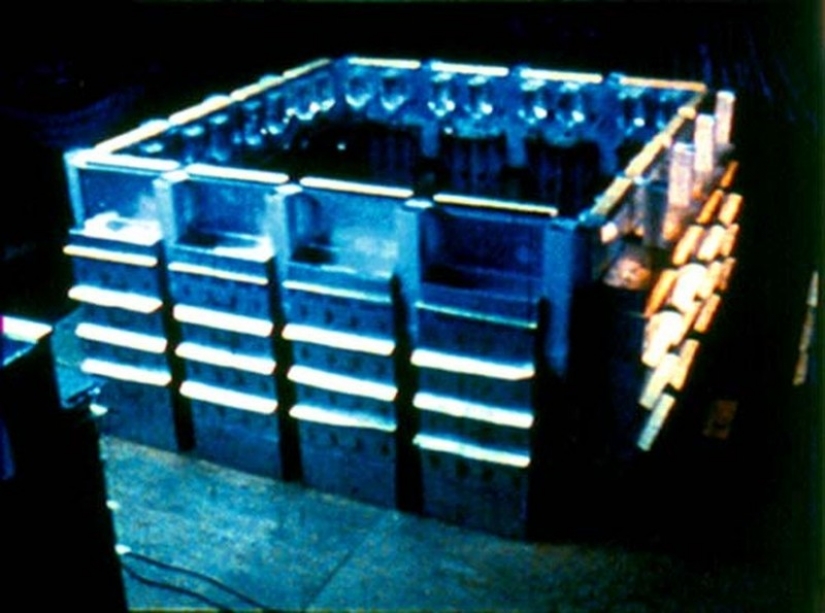

Like the brutalist architects of the era, Calhoun’s next experiment was bigger and bolder. Inside the second floor of a huge barn, his team constructed a series of four rooms connected by three bridges, forming a U-shaped space. Inside each room was a drinking and feeding station.

Detailing the shocking findings in a Scientific American article, Calhoun revealed how the effects of density led to a brutal battle among males. In the earliest stages, the male rats struggle for status. Once they fixed their place in the social hierarchy, they ruled among the two rooms with only one bridge – the end rooms. This became a dominant male’s territory where females were kept. Most male rats, therefore, congregated in the middle two rooms.

Early in the morning, before the dominant males awoke, the subordinate males would roam the various rooms. However, if in the middle rooms after he awoke, subordinate males found it exceedingly difficult to reach their original quarters. They were trapped. After several defeats, these males would never attempt to cross the bridge. The dominant male would only tolerate subordinate males so long as they never attempted to mate with the members of his harem – and they never did. Rather these subordinate males would often attempt to mount the dominant male, which he generally tolerated.

Females living in the middle rooms, meanwhile, fell into a behavioral sink. They became less adept at building nests before stopping completely. Nor did they move their litter to safety when necessary – unlike the females in the harems. Infants were frequently abandoned and would die when they were dropped. High rates of maternal miscarriage and infant mortality followed.

Connections were naturally drawn to the sink estates and neighborhoods arising in the US and UK. But Calhoun was far from done.

Universe 25 would be his most ambitious experiment; involving a vast space suitable for thousands of mice, Calhoun ensured the mice had ample food, water, and nesting material.

Between day 1 and day 315, the population doubled every 55 days, reaching 620 mice. Following day 315, population growth doubled only every 145 days. During this period, normal mice social behavior broke down. Young mice were cast aside by mothers before they weaned; homosexual behavior became common; dominant males struggled to maintain their territory leading to increasingly aggressive female behavior.

As Calhoun described:

“At the peak population, most mice … [waited] to be fed and occasionally attacked each other. Few females carried pregnancies to term, and the ones that did seemed to simply forget about their babies. They’d move half their litter away from danger and forget the rest. Sometimes they’d drop and abandon a baby while they were carrying it.”

In the final stages of mouse utopia, some young male mice never engaged in sex or fighting. They devoted their time solely to grooming, eating, and sleeping, becoming known as “the beautiful ones.” Despite appearances, these maladaptive mice could not cope with the stresses of life.

By day 600, the mice lost all social skills required to mate. Females ceased to reproduce, and the beautiful ones grew in number, engaging solely in solitary pursuits. When Calhoun wrote the experiment, the final breeding male had died – the mouse utopia was marching toward extinction.

While many have criticized the experiment for its social ramifications, it’s hard not to be alarmed. The parallels with modern-day society are stark. Yet social scientists who have attempted to replicate the findings in humans struggled to find any association between social density and behavior. Whatever your opinion, Calhoun started a conversation that very much continues today.

- https://www.iflscience.com/universe-25-the-mouse-utopia-experiment-that-turned-into-an-apocalypse-60407

- https://everything-everywhere.com/universe-25-the-rat-utopia-which-became-a-rate-dystopia/

- https://fee.org/articles/john-b-calhoun-s-mouse-utopia-experiment-and-reflections-on-the-welfare-state/

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/how-mouse-utopias-1960s-led-grim-predictions-humans-180954423/

Share this:

Categories: Behavioral Science , History

Tagged as: Dystopia , Ethics , John Calhoun , Morality , Psychology , Rat Utopia , Society

Published by MPSWriterJoe

Philosophy writer View all posts by MPSWriterJoe

1 reply »

https://fineartamerica.com/featured/behavioral-sink-dawn-sperry.html https://fineartamerica.com/featured/unincumbered-dawn-sperry.html Thank you for more thorough coverage than what I found in creating the two above excerpts for a novelty newspaper and cartoon tabloid. Best Regards, Dawn

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

Upcoming Events

Recent posts.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

The Doomed Mouse Utopia That Inspired the ‘Rats of NIMH’

Dr. john bumpass calhoun spent the ’60s and ’70s playing god to thousands of rodents..

On July 9th, 1968, eight white mice were placed into a strange box at the National Institute of Health in Bethesda, Maryland . Maybe “box” isn’t the right word for it; the space was more like a room, known as Universe 25, about the size of a small storage unit. The mice themselves were bright and healthy, hand-picked from the institute’s breeding stock. They were given the run of the place, which had everything they might need: food, water, climate control, hundreds of nesting boxes to choose from, and a lush floor of shredded paper and ground corn cob.

This is a far cry from a wild mouse’s life—no cats, no traps, no long winters. It’s even better than your average lab mouse’s, which is constantly interrupted by white-coated humans with scalpels or syringes. The residents of Universe 25 were mostly left alone, save for one man who would peer at them from above, and his team of similarly interested assistants. They must have thought they were the luckiest mice in the world. They couldn’t have known the truth: that within a few years, they and their descendants would all be dead.

The man who played mouse-God and came up with this doomed universe was named John Bumpass Calhoun. As Edmund Ramsden and Jon Adams detail in a paper, “ Escaping the Laboratory: The Rodent Experiments of John B. Calhoun & Their Cultural Influence ,” Calhoun spent his childhood traipsing around Tennessee , chasing toads, collecting turtles, and banding birds. These adventures eventually led him to a doctorate in biology, and then a job in Baltimore , where he was tasked with studying the habits of Norway rats, one of the city’s chief pests.

In 1947, to keep a close eye on his charges, Calhoun constructed a quarter-acre “rat city” behind his house, and filled it with breeding pairs. He expected to be able to house 5,000 rats there, but over the two years he observed the city, the population never exceeded 150. At that point, the rats became too stressed to reproduce. They started acting weirdly, rolling dirt into balls rather than digging normal tunnels. They hissed and fought.

This fascinated Calhoun—if the rats had everything they needed, what was keeping them from overrunning his little city, just as they had all of Baltimore?

Intrigued, Calhoun built another, slightly bigger rat metropolis—this time in a barn, with ramps connecting several different rooms. Then he built another and another, hopping between patrons that supported his research, and framing his work in terms of population: How many individuals could a rodent city hold without losing its collective mind? By 1954, he was working under the auspices of the National Institute of Mental Health, which gave him whole rooms to build his rodentopias. Some of these featured rats, while others focused on mice instead. Like a rodent real estate developer, he incorporated ever-better amenities: climbable walls, food hoppers that could serve two dozen customers at once, lodging he described as “walk-up one-room apartments.” Video records of his experiments show Calhoun with a pleased smile and a pipe in his mouth, color-coded mice scurrying over his boots.

Still, at a certain point, each of these paradises collapsed. “There could be no escape from the behavioral consequences of rising population density,” Calhoun wrote in an early paper . Even Universe 25—the biggest, best mousetopia of all, built after a quarter century of research—failed to break this pattern. In late October, the first litter of mouse pups was born. After that, the population doubled every two months—20 mice, then 40, then 80. The babies grew up and had babies of their own. Families became dynasties, carving out and holding down the best in-cage real estate. By August of 1969, the population numbered 620.

Then, as always, things took a turn. Such rapid growth put too much pressure on the mouse way of life. As new generations reached adulthood, many couldn’t find mates, or places in the social order—the mouse equivalent of a spouse and a job. Spinster females retreated to high-up nesting boxes, where they lived alone, far from the family neighborhoods. Washed-up males gathered in the center of the Universe, near the food, where they fretted, languished, and attacked each other. Meanwhile, overextended mouse moms and dads began moving nests constantly to avoid their unsavory neighbors. They also took their stress out on their babies, kicking them out of the nest too early, or even losing them during moves.

Population growth slowed way down again. Most of the adolescent mice retreated even further from societal expectations, spending all their time eating, drinking, sleeping and grooming, and refusing to fight or to even attempt to mate. (These individuals were forever changed—when Calhoun’s colleague attempted to transplant some of them to more normal situations, they didn’t remember how to do anything.) In May of 1970, just under 2 years into the study, the last baby was born, and the population entered a swan dive of perpetual senescence. It’s unclear exactly when the last resident of Universe 25 perished, but it was probably sometime in 1973.

Paradise couldn’t even last half a decade.

In 1973, Calhoun published his Universe 25 research as “Death Squared: The Explosive Growth and Demise of a Mouse Population.” It is, to put it lightly, an intense academic reading experience. He quotes liberally from the Book of Revelation, italicizing certain words for emphasis (e.g. “to kill with the sword and with famine and with pestilence and by wild beasts ”). He gave his claimed discoveries catchy names—the mice who forgot how to mate were “the beautiful ones”’ rats who crowded around water bottles were “social drinkers”; the overall societal breakdown was the “behavioral sink.” In other words, it was exactly the kind of diction you’d expect from someone who spent his entire life perfecting the art of the mouse dystopia.

Most frightening are the parallels he draws between rodent and human society. “I shall largely speak of mice,” he begins, “but my thoughts are on man.” Both species, he explains, are vulnerable to two types of death—that of the spirit and that of the body. Even though he had removed physical threats, doing so had forced the residents of Universe 25 into a spiritually unhealthy situation, full of crowding, overstimulation, and contact with various mouse strangers. To a society experiencing the rapid growth of cities—and reacting, in various ways, quite poorly — this story seemed familiar. Senators brought it up in meetings. It showed up in science fiction and comic books. Even Tom Wolfe, never lost for description, used Calhounian terms to describe New York City, calling all of Gotham a “behavioral sink.”

Convinced that he had found a real problem, Calhoun quickly began using his mouse models to try and fix it. If mice and humans weren’t afforded enough physical space, he thought, perhaps they could make up for it with conceptual space—creativity, artistry, and the type of community not built around social hierarchies. His later Universes were designed to be spiritually as well as physically utopic, with rodent interactions carefully controlled to maximize happiness (he was particularly fascinated by some early rats who had created an innovative form of tunneling, where they rolled dirt into balls). He extrapolated this, too, to human concerns, becoming an early supporter of environmental design and H.G. Wells’s hypothetical “World Brain,” an international information network that was a clear precursor to the internet.

But the public held on hard to his earlier work—as Ramsden and Adams put it, “everyone want[ed] to hear the diagnosis, no one want[ed] to hear the cure.” Gradually, Calhoun lost attention, standing, and funding. In 1986, he was forced to retire from the National Institute of Mental Health. Nine years later, he died.

But there was one person who paid attention to his more optimistic experiments, a writer named Robert C. O’Brien. In the late ’60s, O’Brien allegedly visited Calhoun’s lab , met the man trying to build a true and creative rodent paradise, and took note of the Frisbee on the door, the scientists’ own attempt “to help when things got too stressful,” as Calhoun put it. Soon after, O’Brien wrote Ms. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH —a story about rats who, having escaped from a lab full of blundering humans, attempt to build their own utopia. Next time, maybe we should put the rats in charge.

Naturecultures is a weekly column that explores the changing relationships between humanity and wilder things. Have something you want covered (or uncovered)? Send tips to [email protected] .

This Woman's Ongoing Fight for the Right to Live in a Treehouse

Using an ad blocker?

We depend on ad revenue to craft and curate stories about the world’s hidden wonders. Consider supporting our work by becoming a member for as little as $5 a month.

Podcast: APOPO Rats

In Colonial Williamsburg, Thieving Rats Save History

Meet the Rats That Wear Protective Poison Armor

How South Jersey Keeps Muskrat on the Menu

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Pre-Order Atlas Obscura: Wild Life Today!

Add some wonder to your inbox, we'd like you to like us.

Distillations magazine

Mouse heaven or mouse hell.

Biologist John Calhoun’s rodent experiments gripped a society consumed by fears of overpopulation.

Officially, the colony was called the Mortality-Inhibiting Environment for Mice. Unofficially, it was called mouse heaven.

Biologist John Calhoun built the colony at the National Institute of Mental Health in Maryland in 1968. It was a large pen—a 4½-foot cube—with everything a mouse could ever desire: plenty of food and water; a perfect climate; reams of paper to make cozy nests; and 256 separate apartments, accessible via mesh tubes bolted to the walls. Calhoun also screened the mice to eliminate disease. Free from predators and other worries, a mouse could theoretically live to an extraordinarily old age there, without a single worry.

But the thing is, this wasn’t Calhoun’s first rodent utopia. This was the 25th iteration. And by this point he knew how quickly mouse heaven could deteriorate into mouse hell.

John Calhoun grew up in Tennessee, the son of a high school principal and an artist, and was an avid birder when young. After earning his PhD in zoology, he joined the Rodent Ecology Project in Baltimore in 1946, whose purpose was to eliminate rodent pests in cities. The project had limited success, partly because no one could figure out what aspects of rodent behavior, lifestyle, or biology to target. Calhoun set up his first utopia, involving Norway rats, in the woods behind his house to monitor rodents over time and figure out what factors drove their population growth.

Eventually Calhoun grew fascinated with the rodent behavior for its own sake and began crafting ever more elaborate and carefully controlled environments. It wasn’t just the behavior of rats that interested him. Architects and civil engineers at the time were having vigorous debates about how to build better cities, and Calhoun imagined urban design might be studied in rodents first and then extrapolated to human beings.

Calhoun’s most famous utopia, number 25, began in July 1968, when he introduced eight albino mice into the 4½-foot cube. Following an adjustment period, the first pups were born 3½ months later, and the population doubled every 55 days afterward. Eventually this torrid growth slowed, but the population continued to climb, peaking at 2,200 mice during the 19th month.

That robust growth masked some serious problems, however. In the wild, infant mortality among mice is high, as most juveniles get eaten by predators or perish of disease or cold. In mouse utopia, juveniles rarely died. As a result, there were far more youngsters than normal, which introduced several difficulties.

Rodents have social hierarchies, with dominant alpha males controlling harems of females. Alphas establish dominance by fighting—wrestling and biting any challengers. Normally a mouse that loses a fight will scurry off to some distant nook to start over elsewhere.

But in mouse utopia, the losing mice couldn’t escape. Calhoun called them “dropouts.” And because so few juveniles died, huge hordes of dropouts would gather in the center of the pen. They were full of cuts and ugly scars, and every so often huge brawls would break out—vicious free-for-alls of biting and clawing that served no obvious purpose. It was just senseless violence. (In earlier utopias involving rats, some dropouts turned to cannibalism.)

Alpha males struggled, too. They kept their harems in private apartments, which they had to defend from challengers. But given how many mice survived to adulthood, there were always a dozen hotshots ready to fight. The alphas soon grew exhausted, and some stopped defending their apartments altogether.

As a result, apartments with nursing females were regularly invaded by rogue males. The mothers fought back, but often to the detriment of their young. Many stressed-out mothers booted their pups from the nest early, before the pups were ready. A few even attacked their own young amid the violence or abandoned them while fleeing to different apartments, leaving the pups to die of neglect.

Eventually other deviant behavior emerged. Mice who had been raised improperly or kicked out of the nest early often failed to develop healthy social bonds, and therefore struggled in adulthood with social interactions. Maladjusted females began isolating themselves like hermits in empty apartments—unusual behavior among mice. Maladjusted males, meanwhile, took to grooming all day—preening and licking themselves hour after hour. Calhoun called them “the beautiful ones.” And yet, even while obsessing over their appearance, these males had zero interest in courting females, zero interest in sex.

Intriguingly, Calhoun had noticed in earlier utopias that such maladjusted behavior could spread like a contagion from mouse to mouse. He dubbed this phenomenon “the behavioral sink.”

Between the lack of sex, which lowered the birth rate, and inability to raise pups properly, which sharply increased infant mortality, the population of Universe 25 began to plummet. By the 21st month, newborn pups rarely survived more than a few days. Soon, new births stopped altogether. Older mice lingered for a while—hiding like hermits or grooming all day—but eventually they died out as well. By spring 1973, less than five years after the experiment started, the population had crashed from 2,200 to 0. Mouse heaven had gone extinct.

Universe 25 ended a half century ago, but it continues to fascinate people today—especially as a gloomy metaphor for human society. Calhoun actively encouraged such speculation, once writing, “I shall largely speak of mice, but my thoughts are on man.” As early as 1968, journalist Tom Wolfe titled an essay about New York “O Rotten Gotham—Sliding Down into the Behavioral Sink.” Oddly, though, none of the prognosticators could agree on the main lesson of Universe 25.

The first people to fret over Universe 25 were environmentalists. The same year the study began, biologist Paul Ehrlich published The Population Bomb , an alarmist book predicting imminent starvation and population crashes due to overpopulation on Earth. Pop culture picked up on this theme in movies, such as Soylent Green , where humans in crowded cities are culled and turned into food slurry. Overall, the idea of dangerous overcrowding was in the air, and some sociologists explicitly drew on Calhoun’s work, writing: “We . . . take the animal studies as a serious model for human populations.” The message was stark: Curb population growth—or else .

More recently scholars saw similarities to the Industrial Revolution and the rise of modern urban society. The 19th and 20th centuries saw population booms across the world, largely due to drops in infant mortality—similar to what the mice experienced. Recently, however, human birth rates have dropped sharply in many developed countries—often below replacement levels—and young people in those places have reportedly lost interest in sex. The parallels to Universe 25 seem spooky.

Behavioral biologists have echoed the eugenics movement in blaming the strange behaviors of the mice on a lack of natural selection, which in their view culls those they consider weak and unfit to breed. This lack of culling resulted in supposed “mutational meltdowns” that led to widespread mouse stupidity and aberrant behavior. (The researchers argued that the brain is especially susceptible to mutations because it’s so intricate and because so many of our genes influence brain function.)

Extrapolating from this work, some political agitators warn that humankind will face a similar decline. Women are supposedly falling into Calhoun’s behavioral sink by learning “maladaptive behaviors,” such as choosing not to have children, which “destroy[s] their own genetic interests.” Other critics agonize over the supposed loss of traditional gender roles, leaving effete males and hyperaggressive females, or they deplore the undermining of religions and their imperatives to “be fruitful and multiply.” In tandem, such changes will lead to the “decline of the West.”

Still others have cast Universe 25’s collapse as a parable illustrating the dangers of socialist welfare states, which, they argue, provide material goods but remove healthy challenges from people’s lives, challenges that build character and promote “personal growth.” Another school of thought viewed Universe 25 as a warning about “the city [as] a perversion of nature.” As sociologists Claude Fischer and Mark Baldassare put it, “A red-eyed, sharp-fanged obsession about urban life stalks contemporary thought.”

Most critics who’ve fretted over Calhoun’s work cluster on the conservative end of the political spectrum, but self-styled progressives have weighed in as well. Advocates for birth control repeatedly invoked Calhoun’s mice as a cautionary tale about how runaway population growth destroys family life. More recent interpretations see the mice collapse in terms of one-percenters and wealth inequality; they blame the social dysfunction on a few aggressive males hoarding precious resources (e.g., desirable apartments). In this view, said one critic, “Universe 25 had a fair distribution problem” above all.

Given these wildly varying (even contradictory) readings, it’s hard to escape the suspicion that personal and political views, rather than objective inquiry, are driving these critics’ outlooks. And indeed, a closer look at the interpretations severely undermines them.

When forecasting population crashes among human beings, Population Bomb –type environmentalists invariably predicted that overcrowding would lead to widespread shortages of food and other goods. That’s actually the opposite of what Universe 25 was like. The mice there had all the goods they wanted. This also undermines arguments about unfair resource distribution.

Perhaps, then, it was the lack of struggles and challenges that led to dysfunction, as welfare critics claimed. Except that the spiral of dysfunction began when hordes of “dropout” mice lost challenges to alpha males, couldn’t escape elsewhere, and began brawling in the middle of the pen. The alpha males in turn grew weary after too many challenges from youngsters. Indeed, most mice faced competition far in excess of what they would encounter in the wild.

The appearance of the sexless “beautiful ones” does seem decadent and echoes the reported loss of interest in sex among young people in developed countries. Except that a closer look at the survey data indicates that such worries might be overblown. And any comparison between human birth rates and Universe 25 birth rates is complicated by the fact that the mouse rates dropped partly due to infant neglect and spikes in infant mortality—the opposite of the situation in the developed world.

Then there are the warnings about the mutational meltdown and the decline of intelligence. Aside from echoing the darkest rhetoric of the eugenics movement, this interpretation runs aground on several points. The hermit females and preening, asexual males certainly acted oddly—but in doing so, they avoided the vicious, violent free-for-alls that beset earlier generations. This hardly seems dumb. Moreover, some of Calhoun’s research actually saw rodents getting smarter during experiments.

This evidence came from an earlier utopia involving rats. In that setup, dropout rats began digging new burrows into the dirt floor of their pen. Digging produces loose dirt to clear away, and most rats laboriously carried the loose dirt outside the tunnel bit by bit, to dump it there. It’s necessary but tedious work.

But some of the dropout rats did something different. Instead of carrying dirt out bit by bit, they packed it all into a ball and rolled it out the tunnel in one trip. An enthused Calhoun compared this innovation to humankind inventing the wheel. And it happened only because the rats were isolated from the main group and didn’t learn the dominant method of digging. By normal rat standards, this was deviant behavior. It was also a creative breakthrough. Overall, then, Calhoun argued that social strife can sometimes push creatures to become smarter, not dumber.

(Incidentally, after Universe 25’s collapse, Calhoun began building new utopias to encourage creative behavior by keeping mice physically and mentally nourished. This research, in turn, inspired a children’s book named after Calhoun’s workplace— Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH , wherein a group of rats escape from a colony designed to stimulate their intelligence.)

So if all these interpretations of Universe 25 miss the mark, what lesson can we draw from the experiment?

Calhoun’s big takeaway involved status. Again, the males who lost the fights for dominance couldn’t leave to start over elsewhere. As he saw it, they were stuck in pathetic, humiliating roles and lacked a meaningful place in society. The same went for females when they couldn’t nurse or raise pups properly. Both groups became depressed and angry, and began lashing out. In other words, because mice are social animals, they need meaningful social roles to feel fulfilled. Humans are social animals as well, and without a meaningful role, we too can become hostile and lash out.

Still, even this interpretation seems like a stretch. Humans have far more ways of finding meaning in life than pumping out children or dominating some little hierarchy. And while human beings and mice are indeed both social creatures, that common label papers over some major differences. Critics of Calhoun’s work argued that population density among humans—a statistical measure—doesn’t necessarily correlate with crowding —a feeling of psychological stress. In the words of one historian, “Through their intelligence, adaptability, and capacity to make the world around them, humans were capable of coping with crowding” in ways that mice simply are not.

Ultimately Calhoun’s work functions like a Rorschach blot—people see what they want to see. It’s worth remembering that not all lab experiments, especially contrived ones such as Universe 25, apply to the real world. In which case, perhaps the best lesson to learn here is a meta-lesson: that drawing lessons itself can be a dangerous thing.

Sam Kean is a best-selling science author. His latest book is The Icepick Surgeon: Murder, Fraud, Sabotage, Piracy, and Other Dastardly Deeds Perpetrated in the Name of Science .

More from our magazine

That Time Demons Possessed the Telegraph

Solar storms from long ago have become the delight of some scientists—and the dread of others.

21 Years, 7,600 Tests

Mary Papanicolaou, the woman behind the man behind the Pap smear.

Controversy, Control, and Cosmetics in Early Modern Italy

In a society that damned women for both plainness and adornment, wearing makeup became a defiant act of survival.

Copy the above HTML to republish this content. We have formatted the material to follow our guidelines, which include our credit requirements. Please review our full list of guidelines for more information. By republishing this content, you agree to our republication requirements.

Infamous Universe 25 'Rodent Utopia' Experiment Is Not a Sign of the Apocalypse

Many people have used john calhoun's "rodent utopia" experiments as scientific evidence for "social decay" in humans., published may 27, 2024.

People predicting the end of world generally make those predictions without scientific evidence to support them. So when an animal-behavior researcher ran experiments in the 1960s that described "utopian" rodent societies pushing themselves into extinction, scientists and the general public alike took notice. That attention never fully went away.

Ever since the original "Universe 25" rodent utopia experiment took place, countless people have discussed the study and its findings, with some suggesting it could be an apocalyptic prediction for the future of humanity. The story pops up online every so often, and Snopes readers have written many emails over the past few years asking us about the notorious rodent utopia experiment.

The Background

Before explaining the experiment, it's important to understand why it was performed. While environmentalism as a political theory had been around in bits and pieces since the early days of the Industrial Revolution, it was not until just after World War II that people truly began to politically organize around the environment.

One of the largest fears at the time was overpopulation — sometimes called Malthusianism after an 18th-century demographer, Thomas Malthus , who proposed that population would eventually grow faster than food production, meaning that, eventually, humanity would be unable to feed everyone. Many early environmentalists proposed similar ideas.

In the 1950s, an animal behaviorist named John Calhoun started working at the National Institute of Mental Health. He had long worked with rats, the subject of his Ph.D. thesis, and was interested in studying how a rat society would develop over time when it was limited only by space. In other words, he wanted to test the effects of overpopulation.

In order to run his experiment, Calhoun designed complexes, which he named "Universes," that would provide his rodent subjects all they needed to survive — food, water and protection from predators and disease. The only thing that would limit the population growth would be space.

As he watched the rodent societies grow, he began noticing strange trends:

Pregnant females began having problems raising offspring. Dominant males became incredibly territorial and overactive, while subordinate males increasingly withdrew from the larger group, coming out "to eat, drink and move about only when other members of the community were asleep." Rats became so conditioned to eating with others that they would refuse to eat alone. Some males became hypersexual and attempted to mate with anyone and everyone. Fighting was frequent. Rats began cannibalizing other rats. At one point, the infant mortality rate reached an astonishing 96%.

As one of Calhoun's assistants put it, "utopia" had turned into a "hell."

The Experiments

Calhoun published the results of his early experiments in the February 1962 edition of Scientific American, with the title " Population Density and Social Pathology ," coining the term " behavioral sink " to describe the most-crowded spots, where he observed the highest rate of antisocial behavior. In the 1960s, at the height of political discourse about so-called "social decay" in American cities, the study was a natural discussion topic. In the meantime, Calhoun continued his work.

And now we arrive the 25th version of this study Calhoun ran, and the one he would become most well-known for: Universe 25. It was the only one of Calhoun's habitats fully studied from beginning to end. Universe 25 was populated with mice instead of rats, but most everything else remained the same. Mice had everything they needed to survive and were limited only by space.

Calhoun constructed a square box with a side length of 54 inches. He built nesting boxes, water bottles and food hoppers into the walls, with each side of the universe having 64 different nesting boxes located at various heights, 16 water bottles and four food hoppers. All of the "utilities" were accessible via a series of mesh tunnels running from the floor up the side of the wall.

Calhoun published the results of Universe 25 in 1973 in a paper called " Death Squared: The Explosive Growth and Demise of a Mouse Population ." He broke down the development and collapse of the society into four phases:

- Phase A, consisting of the first 104 days, was the adjustment phase, with "considerable social turmoil" between the eight original mice placed into the habitat. Phase A ended once the mice had their first offspring.

- Phase B, which Calhoun named the resource exploitation phase, lasted from Day 105 to Day 315. During this phase, the population grew rapidly, reaching more than 600 mice before growth began slowing. Social stratification also began to happen, with different groups of mice living in certain areas and self-selecting into their own independent groups.

- Phase C, called the stagnation phase, lasted from Day 316 to Day 560. Male mice who were not able to find room in the pre-existing social structure began to withdraw from society, violently attacking one another. Their female counterparts retreated into the highest boxes, also isolating themselves. Socially dominant males began to lose control over their territory, leaving mothers to aggressively defend their young, sometimes even abandoning them. "For all practical purposes there had been a death of societal organization by the end of Phase C," Calhoun wrote.

- Phase D was the death phase. The death rate outpaced the birth rate, and the society began to shrink. Mothers raised newborn mice for a very short time, and Calhoun proposed that the young generation's strange behaviors were a direct result of a very abnormal social upbringing that did not allow some of the more "complex behaviors," including mating rituals, to develop. Females rarely gave birth, and a large group of males, which Calhoun named the "beautiful ones," did nothing other than eat, drink, sleep and groom themselves. During Phase D, a few mice were placed in newly established universes to see whether they would relearn those social behaviors. They did not.

Calhoun's 1973 paper was not subtle. "I shall largely speak of mice, but my thoughts are on man, on healing, on life and its evolution," he wrote. He made frequent references to the Book of Revelation in the Bible and almost all of his wording aimed to personify his rodent subjects. The mice in Universe 25 lived in "walk-up apartments," and Calhoun described subgroups like "somnambulists" or the "bar flies," terms that could easily be mapped to urban life.

The conclusions felt grim, and the fears of overpopulation made their way into pop culture , like the movie "Soylent Green." There's even a book for children very loosely based around Calhoun's mouse cities (although without the doom and gloom of societal breakdown): "Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH."

The Conclusions

In modern times, Calhoun's Universe 25 experiment is often used as a way to talk about some kind of " degradation of Western society ." These analyses look at Calhoun's experiments and say, "He predicted this would happen to humans, and look at all the cultural degeneracy we see today!" For instance, here's an excerpt from a comment about the experiment we've seen repeatedly on Facebook :

According to Calhoun, the death phase consisted of two stages: the "first death" and "second death." The former was characterized by the loss of purpose in life beyond mere existence — no desire to mate, raise young or establish a role within society. As time went on, juvenile mortality reached 100% and reproduction reached zero. Among the endangered mice, homosexuality was observed and, at the same time, cannibalism increased, despite the fact that there was plenty of food. Two years after the start of the experiment, the last baby of the colony was born. By 1973, he had killed the last mouse in the Universe 25. John Calhoun repeated the same experiment 25 more times, and each time the result was the same. Calhoun's scientific work has been used as a model for interpreting social collapse, and his research serves as a focal point for the study of urban sociology. We are currently witnessing direct parallels in today's society ... weak, feminized men with little to no skills and no protection instincts, and overly agitated and aggressive females with no maternal instincts.

Scientists have repeatedly pushed back against these ideas since Calhoun's research came out. Researchers who attempted to replicate Calhoun's studies in humans found mixed results, and other scientists chastised him for extrapolating rodent behavior to humans. While the popular conception of Universe 25 focused on the apocalyptic death of society because of overpopulation, other psychologists suggested otherwise.

In an 2008 interview with the NIH Record , Dr. Edmund Ramsden, a science historian, explained the results of a similar 1975 experiment by a psychologist Jonathan Freedman:

Freedman's work, Ramsden noted, suggested that density was no longer a primary explanatory variable for society's ruin. A distinction was drawn between animals and humans. "Rats may suffer from crowding; human beings can cope… Calhoun's research was seen not only as questionable, but also as dangerous." Freedman suggested a different conclusion, though. Moral decay resulted "not from density, but from excessive social interaction," Ramsden explained. "Not all of Calhoun's rats had gone berserk. Those who managed to control space led relatively normal lives." Striking the right balance between privacy and community, Freedman argued, would reduce social pathology. It was the unwanted unavoidable social interaction that drove even fairly social creatures mad, he believed.

But what the modern critics often carelessly and conveniently leave out is how Calhoun's research evolved after Universe 25: Up until his death in 1995, Calhoun looked for solutions to the problem he had discovered, altering his designs and controls to try to avoid the societal collapse of Universe 25. He described rodents coming up with creative solutions to daily tasks. And it was in this way that his experiments have actually proven more useful. Architects and urban designers have taken Calhoun's experiments into consideration when designing buildings and cities. Prison researchers and reformers have also found Calhoun's studies surprisingly helpful.

So yes, while Universe 25 and Calhoun's "rodent utopias" were real experiments, they're not the apocalyptic predictions that some people make them out to be.

Arnason, Gardar. "The Emergence and Development of Animal Research Ethics: A Review with a Focus on Nonhuman Primates." Science and Engineering Ethics , vol. 26, no. 4, 2020, pp. 2277–93. PubMed Central , https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-020-00219-z.

Britannica Money . 18 Mar. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/money/Malthusianism.

Calhoun, John B. "Death Squared: The Explosive Growth and Demise of a Mouse Population." Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine , vol. 66, no. 1P2, Jan. 1973, pp. 80–88. DOI.org (Crossref) , https://doi.org/10.1177/00359157730661P202.

Calhoun, John B. "Population Density and Social Pathology." California Medicine , vol. 113, no. 5, Nov. 1970, p. 54. PubMed Central , https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1501789/.

---. "Space and the Strategy of Life." Behavior and Environment: The Use of Space by Animals and Men , edited by Aristide Henri Esser, Springer US, 1971, pp. 329–87. Springer Link , https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-1893-4_25.

Edmund Ramsden and Jon Adams. "Escaping the Laboratory: The Rodent Experiments of John B. Calhoun & Their Cultural Influence." Journal of Social History , vol. 42, no. 3, 2009, pp. 761–92. DOI.org (Crossref) , https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh.0.0156.

Environmentalism | Ideology, History, & Types | Britannica . https://www.britannica.com/topic/environmentalism. Accessed 17 May 2024.

Fredrik Knudsen. The Mouse Utopia Experiments | Down the Rabbit Hole . 2017. YouTube , https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NgGLFozNM2o.

Garnett, Carla. "Medical Historian Examines NIMH Experiments In Crowding." NIH Record , Vol. LX, No. 15, 25 July 2008, https://nihrecord.nih.gov/sites/recordNIH/files/pdf/2008/NIH-Record-2008-07-25.pdf.

Magazine, Smithsonian, and Maris Fessenden. "How 1960s Mouse Utopias Led to Grim Predictions for Future of Humanity." Smithsonian Magazine , https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/how-mouse-utopias-1960s-led-grim-predictions-humans-180954423/. Accessed 17 May 2024.

Magazine, Smithsonian, and Charles C. Mann. "The Book That Incited a Worldwide Fear of Overpopulation." Smithsonian Magazine , https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/book-incited-worldwide-fear-overpopulation-180967499/. Accessed 17 May 2024.

Paulus, Paul. Prisons Crowding: A Psychological Perspective . Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

Ramsden, Edmund. "The Urban Animal: Population Density and Social Pathology in Rodents and Humans." Bulletin of the World Health Organization , vol. 87, no. 2, Feb. 2009, p. 82. PubMed Central , https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.09.062836.

The Calhoun Rodent Experiments: The Real-Life Rats of NIMH . https://cosmosmagazine.com/science/mathematics/calhoun-rodent-experiments/. Accessed 17 May 2024.

"Universe 25, 1968–1973." The Scientist Magazine® , https://www.the-scientist.com/universe-25-1968-1973-69941. Accessed 17 May 2024.

Woodstream, Woodstream. What Humans Can Learn from Calhoun's Rodent Utopia . https://www.victorpest.com/articles/what-humans-can-learn-from-calhouns-rodent-utopia. Accessed 17 May 2024.

By Jack Izzo

Jack Izzo is a Chicago-based journalist and two-time "Jeopardy!" alumnus.

Article Tags

Welcome to Demystifying Science. We explain confusing and mystified science.

Jul 22 Rat Dystopia

So far, we have discussed the origins of multicellularity, the many paths to multicellularity, and circled back to ask the question - what is life?

This week, we’ll look at another aspect of multicellularity, one that manifests on a community level, rather than the individual level. To do this, we are going to take a closer look at a paper by John B. Calhoun called Population Density and Social Pathology .

I want to look at this paper because the experiments within - an extended trial of rodents in confined conditions - seems to offer perspective on the ways in which a multicellular animal - such as a mouse or rat - functions in the context of a greater whole. The mad-scientist experiment thought up by Calhoun allows us to take a step back and consider what one might be able to say about the human condition, and the ways that our environments affect our psychology.

Though the parallels are tantalizing, it is important to remember that we can’t draw clear parallels between humans and experiments done with rodents under even the best conditions. Mice are mice, rats are rats, humans are humans. There is also the fact that these studies were never repeated. They were enormously time-consuming, and seem like a unique result of a man who had spent his entire life working on progressively larger behavioral studies. It seems like Calhoun may have been the only person who was capable of carrying out the experiments - and the lack of reproducibility comes down to the fact that no one except for him was interested in babysitting a quarter acre of rats for nearly a year and a half.

Whatever the case, Calhoun did something extraordinary. In a large barn on his property, he built an enclosure capable of housing thousands of rats. He provided food, water, shelter, and the rats to enjoy it. After more than a year, he emerged a man certain about the fact that human society was driving people to the brink of madness.

Onwards, to Rat Utopia.

John B. Calhoun’s interest in animal behavior when Mrs. Laskey of the Tennessee Ornithological Society taught him to band birds. He published his first paper on animal behavior at the age of 15, and then continued his study of animal behavior as a student of ethology, animal behavior, at the University of Virginia. During his summers at the university, he continued his ornithology work with the Alexander Wetmore, assistant secretary of the Smithsonian Institution.

During his PhD his attention shifted closer to Earth, when he began his studies of the 24hr rhythms of the Norway rat. Whatever he found in these studies was enough to keep his attention for the rest of his life, trudging ever-deeper into the complex world of rodent social behavior. His first foray into large-scale explorations of rodent behavior took place shortly after his appointment to the Rodent Ecology Project at Johns Hopkins University in 1948.

Inspired by what he was discovering at the university, he convinced a neighbor to let him borrow a 1/4 acre plot of unused, forested land. On it, he constructed a 10,000 square foot pen that was open to the elements. He stocked it with ample food, water, and material for building shelters, and dubbed it “Rat Utopia” - the kind of place where a rat would never want for anything. He estimated that the enclosure was large enough to house 5,000 rats, but he was unsure of where the population would stabilize, or what phases it would transition through on its way there. To find out, je seeded the pen with five pregnant females and sat back.

For 28 months, he tracked the rodent populations in the pen, noting any behavioral and social changes. During the two years that he monitored his colony, he found some oddities - the number of rats in the population never exceeded 200 - despite his earlier calculations of a 5,000 rat carrying capacity. In addition to the surprisingly low population density, the distribution of the rats through the enclosure wasn’t uniform. Instead, rats would organize themselves into discrete social units with 12-13 members. He reasoned that this was the natural balance point between a functional society and psychological chaos. Any more individuals and the group would be forced to splinter into a smaller group - perhaps a reflection of the limited number of stable social connections each rat is capable of forming.

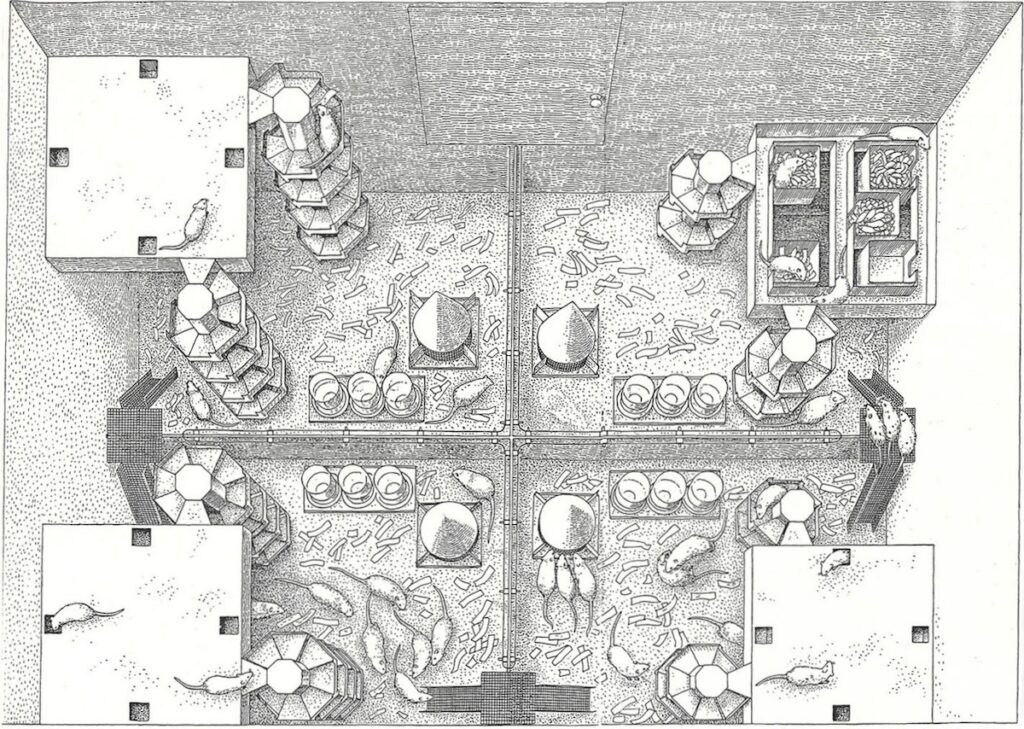

At the end of the experiment, Calhoun was interested in pushing the limits, to see what kinds of changes began to occur as he increased social density - the number of individuals in an enclosure. To this end, he secured a strain of domesticated albino Norwegian rats - the quintessential lab rats - and built an slightly more complex indoor enclosure. This version was significantly smaller than the 1/4 acre pen. It was square, partitioned into four sections, with a pane of glass across the top that allowed the researchers to look into the pen. There was also a door on the side that would allow the researcher access. No photographs of the setup are available, so we will have to rely on the illustrations Calhoun himself made for his Scientific American publication.

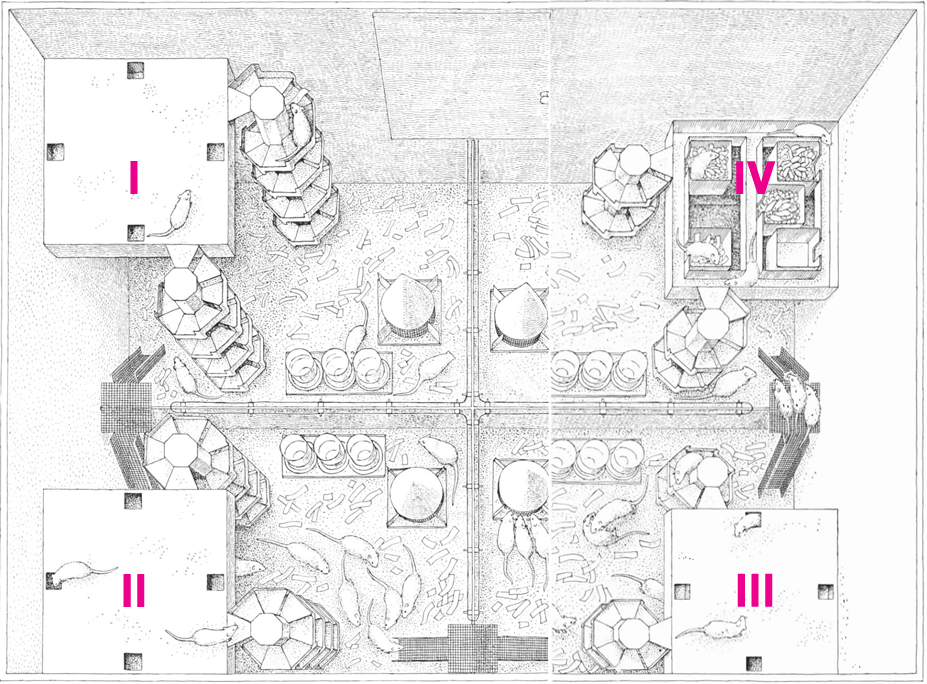

Drawing of Rat Utopia #1. Pens I and IV are not connected to each other, but are connected to pens II and III, respectively. Topology of the enclosure is linear, with pens II and III serving as the center.

There are four chambers, separated by an electrified fence, with a staircase connecting three of four chambers - they are the black grids that bridge compartments I & II, II & III, and III & IV. There is no staircase between chambers I and IV, effectively creating a linear flow through the habitat.

At the edges of each compartment are what amounts to housing towers, with covered nesting quarters at the top of a spiral staircase. Compartment IV shows a cutaway perspective on the tower, demonstrating the apartment-like setup of five nests on the inside. In each compartment there were food containers and water trays, offered ad libitum.

To initiate the experiment, Calhoun seeded the four compartments with an equal number of male-female pairs and waited for their populations to grow to 80 individuals. After that point, he removed any new pups that were born so the population remained stable at 80 individuals. This amounted to 20 individuals per compartment, which was a 75% increase over the preferred group size of 12 in each compartment.

After several months in the pens, he observed that the rats would cluster into a few distinct types of groups - small, medium, and large. The medium groups had equal numbers of male and female rats, but he reliably observed that small groups tend to skew female, while larger groups skewed male. The small groups - i.e. many females to a few males - were found predominantly in the end pens, I and IV, while the larger groups were found predominantly in the center pens, II and III. This meant that the male population was predominantly relegated to those two pens. Overall, the center pens had a much larger population that the end pens.

The mechanism by which this gender and population segregation occurred was aided by a synergy between Calhoun’s design and the process by which the rats oriented themselves in the social hierarchy. Young male rats undergo a period of aggressive status determination, during which they fight for dominance. During this period of fighting, many young rats would awaken early to forage for food before the rest of the colony was active - effectively avoiding the incessant fighting while getting read for the day.

This early rising behavior prevented fights, but paradoxically led to an increased density of males in the two middle compartments. This was likely due to two factors - food and access. Calhoun had developed a special feeding trough, where kibble was hidden behind a wire mesh, that required animals to spend much more time and effort during feeding. Since pens II and III were accessed from two sides, they quickly accumulated a larger population, where this sort of behavior seemed to amplify itself to the degree that Calhoun reported he rarely, if ever, saw animals eating by themselves.

So when male rats in pens I and IV woke up early to go get food, they would go to the main watering holes - pens II and III - to get it. But the dominant males in pen I and IV had set up their living quarters at the bottom of the single ramp that led to those compartments. When these early risers attempted to return, these dominant males would wake and drive them back into the central pen - effectively causing the population density of the central pens to increase, while the peripheral pens lived quite comfortably.

This spontaneous increase in population densities in the central pens of the experiment created what Calhoun referred to as a “behavioral sink,” a situation that far surpassed the population densities the wild rats in the first experiment appeared to prefer. This sort of density resulted in severe disruption of normal rhythms, which Calhoun found to be most apparent in the nesting behavior of the females.

“Rooms” are replicates of an entire 16 month experiment, and pens correspond to roman numerals I-IV. The increases in eating took place in one of the central pens each time a specific kind of food hopper was used. In all three cases, population of the central pens is much greater than the edge pens - though this relative concentration is not the same in all trials. Black and hatched bars represent male female ratios, which are not as robust across populations - or as simple as the story reported by Calhoun in his Scientific American piece.

In the brood pens, the low population I and IV pens, where there was a high female:male ratio, Calhoun measured a 50% survival rate of newborn pups. This seems low, but rats have large litters, up to 15 pups at a time, because in the wild there is some significant percentage that does not survive to adulthood. However, in the females that were in the high-density feeding pens, II and III, between 85 and 90% of the pups died before weaning.

Calhoun attributed this lower likelihood of survival to the overabundance of males that would relentlessly pursue females, whether or not they were willing to mate. This meant that pregnant females, normally free to occupy themselves with the tasks of nestbuilding, were constantly being interrupted by males looking to copulate. This effectively short-circuited the female nesting behavior and although they were pregnant more frequently, they were much worse at taking care of their litters.

The behavioral sink had long-term negative effects for females, who died at a much higher rate than the male rats. By the end of 16 months, a quarter of the females had died from complications with pregnancy or birth - while only 15% of males had died from any cause.

That is not to say, however, that the males didn’t suffer any negative consequences.

Some males managed to avoid the worst of it, and were permitted to remain in these peripheral pens - but in return, these “phlegmatic males” had to accept the dominance of the sentinel without argument. They would spend most of their time burrowed with the females, rarely engaging in sexual behavior of any kind. They would emerge to eat and sleep, and then return to their sleeping quarters until they were stirred by physiological need.

The dominant males that managed to secure brood territories were largely exempt from complication - but in the densely populated middle pens, the fight for dominance never ceased. Periods of relative peace would be interrupted “at regular intervals during the course of their waking hours, [when] the top-ranking males engaged in free-for-alls that culminated in the transfer of dominance from one male to another.” Even those males that succeeded in making it to the top of the hierarchy would periodically go berserk, “attacking females, juveniles and the less active males, and showing a particular predilection -which rats do not normally display - for biting other animals on the tail.”

Those males that did manage to rise to the top of the dominance hierarchy displayed other, abnormal behaviors. There were the pansexuals, who would engage in sexual activity with anyone - male, female, juvenile - that would tolerate their advances. The “somnambulist” rats were the ones that “ignored all the other rats of both sexes, and all the other rats ignored them.” The “probers” were the final group of males that emerged in the densely populated central pens.

They were hyperactive, constantly searching for sexual partners. But their coitus was disturbed, as they would submit to vicious attacks from the dominant rats without defending themselves, and would return, over and over again, to their position at the top of the ladders that led to the brooding pens. There they would wait for passing females with whom they could engage in coitus. These probers were incapable of performing ritual mating practices and would follow females into their burrows to mate - where they would often cannibalize the pups that they found.

At the end of the 16 months, Calhoun selected four of the healthiest males and females and moved them into new living conditions - free from the disquieting density of the interconnected pens. They were six months old, in the prime of their rat lives - but he found that they did not recover normal function. The females gave birth to fewer litters than was expected - and none of the young that were born survived to maturity.

Rats all, folks.

In all, Calhoun repeated the experiment three times and observed similar results with each repetition. In a second round of experiments, he made some modifications to the food hoppers that produced the behavioral sink and found slightly different outcomes. When provided with powdered food rather than the pellets hidden behind a metal mesh, much of the aggregation behaviors around the food disappeared.

The second round of experiments, without the markings of a behavioral sink. The distribution of males and females is much more distinct in this population - with a greater number of females overall, and a greater disparity visible between sex parity in the different pens. Low numbers of males represents a “territory,” controlled by a single dominant male that drives the other males into neighboring pens.

In this second round, it was water that was difficult to get - not food. But for whatever reason - perhaps the lack of dopaminergic effects of drinking water there was less conditioned clustering. The lack of behavioral sinks in the second round of experiments resulted in a much less marked distribution of males and females across the different pens of the experiment - but the behavioral oddities caused by high density remained.

The wire-mesh food hopper used in the experiments that displayed the development of a behavioral sink. Habituation to feeding together at a specific hopper caused a conditioned desire to eat at the same location, in the presence of other rats.

Powder feeder used in the second round of experiments, where rats did not have to spend a significant amount of time acquiring food. The lack of social conditioning prevented the formation of a runaway behavioral sink.

In the years since this study, many have wrestled with what truths might be hidden between the rodent lines. Fears of urban environments affecting normal sexual development, leading to the breakdown of society because of women no longer interested in childrearing, a breakdown of sexual mores, and an acceptance of progressively non-normative sexual behaviors that include asexuality.

Calhoun himself was certain that this was a version of our own society, which would be driven to the brink by overpopulation and overcrowding. But despite numerous attempts in the years following, few researchers were able to find evidence of a behavioral sink - a self-perpetuating behavior that prevented normal functioning - in human societies.

However, it’s possible that researchers didn’t look closely enough to properly interpret urban conditions, or that the definition of a behavioral sink is too simple. It’s also possible that the intervening decades, with an increased push towards LGBTQ acceptance and an increase women’s liberation, have made it difficult to examine Calhoun’s conclusions without threatening the identity of precarious social groups.