- User Manager

- Saved for Later

Critical Thinking for Accountants

by John Taylor

Critical thinking is becoming increasingly important for accountants, as businesses look to you to provide insight, analysis and proposals to improve your, or your clients� business. This course explores critical thinking techniques and provides practical advice on how to use them to benefit the organisations you work with.

Look inside, how it works, this course will enable you to.

- Understand critical thinking and use it to benefit the organisations you work with.

- Overcome the logical fallacies, flawed arguments and unfounded assumptions that lead to bad decisions.

- Improve your decision making by being honest with yourself and reflecting critically.

- Apply critical thinking to present engaging and informative reports.

About the course

Critical thinking is becoming increasingly important for accountants. Your clients are looking to you for more analytical engagement. For accountants in business, critical thinking is an important skill to enable you to help your business achieve its potential.

This course explores critical thinking techniques and provides practical advice and tips on how to use them to benefit the organisations you work with.

- What is critical thinking?

- An important skill

- Why do accountants need critical thinking skills?

- Necessary skills

- Professional scepticism

- Enhancing our work

- Emotional responses

- Cognitive biases

- Logical thinking

- A practical skill

- Practical reasoning

- Judgement statements

- Deductive reasoning

- Inductive reasoning

- Testing a hypothesis

- Flawed arguments

- Professional judgement

- Learning to reflect

- Critical reflection

- Dealing with doubt

- For the avoidance of doubt

- Decision-making

- Improving critical thinking skills

- Developing creative solutions

- Objectives and planning

- Setting pen to paper

- Gathering information

- Analysis, analysis, analysis

- A report worth reading

- Drawing conclusions

John Taylor

John is a Chartered Accountant who has spent many years advising small and medium-sized businesses across the North of England. John is the author of two industry standard textbooks: Millichamp - Auditing and Forensic Accounting . He has also written several auditing textbooks for AAT courses.

Why not upgrade?

Find the best way to complete your CPD

You might also like

Take a look at some of our bestselling courses

Do you have the right personality for College?

- Accounting & Payroll

- Business & Administration

- Community & Education

- Graphic & Web Design

- Healthcare Programs

- Technology & Development

- Construction & Inspection

- Hospitality & Tourism

- Legal & Immigration

- Calgary Central

- Calgary Genesis Centre

- Edmonton South

- Edmonton West

- Edmonton Downtown

- Medicine Hat

- Winnipeg South

- Winnipeg North

- CALGARY GENESIS CENTRE (NEW)

- International Students

- Request Info

Why Critical Thinking Is Important for Careers in Accounting

Critical thinking skills are an asset in every industry, but some might be surprised to know that this type of thinking is especially important for success in accounting careers. Accounting is not all about crunching numbers, as one might think. Accounting professions have evolved, with advancements in technology and changes within various industries. Today, those in the accounting professions need to be able to implement strategies of critical thinking in order to analyze information, determine problems or areas of improvement, and develop logical solutions.

The moment when you apply critical thinking skills to a career in accounting, you’ll ensure a successful future for yourself in the industry. Here’s what critical thinking looks like, and why it’s important for accounting professionals.

What You Should Know That Defines Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is an innovative way of thinking in which someone assesses a problem by raising important questions, and wondering what can be improved upon. A critical thinker gathers new information that can be used to analyze and inform unique strategies to address an issue at hand. Critical thinkers are open-minded and accepting of unconventional approaches, rather than developing attachments to traditional schools of thought.

The work of those with careers in accounting increasingly takes place in more complex environments, and accounting professionals are tackling new kinds of issues. By using critical thinking, an accounting professional looks beyond the numbers and conventional processes in place to determine new strategies, and increase the effectiveness of workflows.

Why Critical Thinking is Important for Accounting Professions

Today, accounting professions look a lot different than they did twenty, or even ten years ago. Those in the accounting professions are often in charge of updating the financial frameworks of an organization to fit with the changes brought on by advancements in technology. Thanks to the integration of automated processes and calculations, the accounting industry has shifted from a focus on spreadsheets and specificities to the practical, hands-on implementation of innovative accounting strategies. Accounting professionals may be focused on making predictions or helping businesses to create more profitable policies, rather than mechanically crunching an organization’s numbers in line with traditional processes.

Critical thinking is an important skill for those with careers in accounting

Today, professionals with accounting training backgrounds must be able to apply creative solutions to problems that businesses are facing, helping them to keep up with competitors and improve the profitability of their business model. Employers increasingly value accounting professionals who can apply creative thinking skills and problem-solving capabilities in order to come up with solutions based on adept analysis of data and systems knowledge.

Improving Your Critical Thinking Skills

There are a few ways that professionals seeking accounting careers can improve their critical thinking skills. When looking at a situation or a problem, someone can first apply critical thinking by having a good understanding of the goal before attempting to develop solutions. This can be achieved simply by asking: “What is the desired outcome?” Next, critical thinking can be improved upon by becoming aware of inherent biases or attachment to traditional ways of accomplishing a task. By understanding that these biases and understandings have their limits, an individual will be more likely to be able to recognize when something could be improved upon.

Lastly, individuals should conduct research on possible solutions, discussing and collaborating with others who would be able to contribute a unique perspective. By brainstorming and exploring all possible avenues of thought, an individual will prepare themselves to think critically about the situation at hand. Are you ready to apply your critical thinking skills to an accounting course ?

Explore the Academy of Learning Career College’s program options today.

Explore Career Training Programs

- Accounting & Payroll

- Business & Administration

- Community & Education

- Graphic & Web Design

- Hospitality & Tourism

- Technology & Development

You May Also Like

Why math lovers should take accounting administration courses, why manual accounting skills still matter after accounting assistant training, essential payroll clerk skills you’ll learn in career college.

Comments are closed.

- Integrated Learning System (ILS)

- Student Experience

- Schedule Appointment

- Financial Assistance

- Student Success Stories

- Individual Courses

Campus Locations

- Partner Program

- National Website

- Career Advice

- Community Services

- Hospitality

© 2024 Academy of Learning Career College. National Website | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

Critical Thinking in Professional Accounting Practice: Conceptions of Employers and Practitioners

2015, Martin Davies and Ron Barnett (Eds), 2015. The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

In settings of semi-structured interviews accountants and employers, using the informal language of the lifeworld, verbalized how they conceptualize critical thinking in professional accounting practice. From their voices, critical thinking is conceptualized not so much as a cognitive ability but as a kind of purposeful doing and is imbued with desirable traits such as open-mindedness and a persistently questioning mind. Critical thinking is also seen to be associated with high-level interpersonal and writing skills. Related skills, like interpretation, evaluation, and reflective judgment, can be honed if persistently practiced in the classroom.

Related topics

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Creative thinking in accounting education

Last month saw the IgNobel awards for “achievements that first make people laugh, then make them think”. My personal recent favourite is the 2019 award to economics researchers who tested which country’s paper money is best at transmitting dangerous bacteria .

It’s precisely this ‘silly but serious’ theme that struck me when I came across a paper about creative thinking in accounting education by Bonk & Curtis (1998). Critical thinking is often on our radars but creative thinking maybe not so much. When I was a relatively inexperienced teacher I thought accounting educators should stick to teaching the rules. I wasn’t aware of the role that creativity can play. Over the years I’ve come to realise that creativity supports the development of critical thinking skills.

For teachers and accountants, especially those of us who are set in our ways, creativity opens up new perspectives and new ways of doing things. And, for students who may be afraid to give a wrong answer, creativity gives them permission to think differently and express their ideas. Here I highlight three ideas that I use in my classes from Bonk & Curtis .

“Reverse brainstorm”

Reverse brainstorming is an adaptation of brainstorming and involves asking students to address a nonsense scenario. A traditional brainstorming exercise might require a class to consider how to reduce costs per patient in a local hosital. In reverse brainstorming, the question is reversed: “What can be done to increase the costs of a local hospital?” The question is fun and gives students permission to play. They know it isn’t something they would be asked in real life, and it therefore liberates them to come up with wild ideas.

“Six Hats” thinking

Six Hats is based on Edward de Bono’s “ Six Thinking Hats ”. A white hat focuses on information and facts, a red hat deals with hunches and emotions, a green hat signals energy for creative proposals and alternatives, a black hat is for judgment and preventing dangerous actions, a yellow hat represents sunshine and optimism, and a blue hat overviews the whole process.

This idea can easily be extended and adapted, perhaps with the teacher assigning everyone in class a “thinking-related role”, for example summarizer, connector, judge, devil’s advocate, arguer, idea squelcher, questioner, adventurer, protestor, or idealist.

I have found that this frees students to think differently about common situations. It’s fun to play, and on a serious note, you will often be playing the role of questioner ‘playing’ against other roles such as optimists or idealists.

Working backwards

Working Backwards requires students to work from a solution or terminal situation—a bit like the board game “ Guess Who? ”. For example, “I am a particular ratio, can you guess which one I am?”. Students might ask what the ratio attempts to explain, what the input variables are, or perhaps typical values for a specific industry. The teacher might choose to make it more difficult by providing only “yes” or “no” replies.

This is an effective way to motivate students to scaffold their memory—they know the rules and they find it a fun game to play. This idea has also been developed into a number of cases (Bujaki & Durocher, 2012, Crook et al. 2019, Desai et al. 2018, Shette, 2020).

All three ideas effectively combine fun with serious learning. Importantly, they don’t have any cost implications for your school or your students. I teach at a community college where some students struggle to pay for food and rent, so this is a significant consideration.

These activities can be done in a face-to-face environment as well as online, or even asynchronously. This gives you the flexibility to adapt these exercises for almost any teaching environment.

How do you encourage creative thinking in accounting education? Are you discussing non-conventional topics, or maybe teaching in non-conventional ways? Maybe you dress up as a pirate? Or are you using some other silly but serious way to teach accounting? Let us know in the comments below.

About the author

Agatha Engel has been teaching in the US and Europe for the past 15 years. She likes to make accounting meaningful for her students and, if possible, a fun experience. She achieves this by bringing practice and theory together in realistic cases and exercises.

Agatha recently received the “Short Case Award” from the AICPA (American Institute of Certified Public Accountants).

References and further reading

Bonk, C. J., & Smith, G. S. (1998). Alternative instructional strategies for creative and critical thinking in the accounting curriculum. Journal of Accounting Education , 16 (2), 261-293. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0748-5751(98)00012-8 .

Bujaki, M., & Durocher, S. (2012). Industry Identification through Ratio Analysis. Accounting Perspectives , 11 (4), 315-322. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3838.12003 .

Crook, Matthew, Mark Griffiths, and Brian Walkup. “The Case of the Unidentified Energy Companies.” Journal of Finance Case Research , Vol. 18, No. 1 (2018/2019): 25-35. Available at: https://scholarship.rollins.edu/as_facpub/260/ . Accessed 10 October 2022

The de Bono Group LLC, Six Thinking Hats . Available at: https://www.debonogroup.com/services/core-programs/six-thinking-hats/ . Accessed 10 October 2022

Desai, M.A., Fruhan, W.E., Fan, L., Bhatia A. (2018), The Case of the Unidentified Industries-2018, as published by Harvard Business School, 2 pages, Product #: 219046-PDF-ENG, https://hbsp.harvard.edu/product/219046-PDF-ENG . Accessed 10 October 2022

IgNobel Awards, 2022, Reprorted by Ars Technica. Available at: https://arstechnica.com/science/maya-ritual-enemas-and-constipated-scorpions-the-2022-ig-nobel-prize-winners/ . Accessed 10 October 2022

Shette, R. (2020). The Case of the Unidentified Companies From India. In SAGE Business Cases . Indian Institute of Management, Kozhikode. Available at: https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781529751956

This is part of the Pedagogy series of articles

© Accounting Cafe

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Mind the GAAP

This site uses cookies, including third-party cookies, to improve your experience and deliver personalized content.

By continuing to use this website, you agree to our use of all cookies. For more information visit IMA's Cookie Policy .

Change username?

Create a new account, forgot password, sign in to myima.

Multiple Categories

Improving Critical Thinking Skills

November 01, 2021

By: Sonja Pippin , Ph.D., CPA ; Brett Rixom , Ph.D., CPA ; Jeffrey Wong , Ph.D., CPA

Whether working with financial statements, analyzing operational and nonfinancial information, implementing machine learning and AI processes, or carrying out many of their other varied responsibilities, accounting and finance professionals need to apply critical thinking skills to interpret the story behind the numbers.

Critical thinking is needed to evaluate complex situations and arrive at logical, sometimes creative, answers to questions. Informed judgments incorporating the ever-increasing amount of data available are essential for decision making and strategic planning.

Thus, creatively thinking about problems is a core competency for accounting and finance professionals—and one that can be enhanced through effective training. One such approach is through metacognition. Training that employs a combination of both creative problem solving (divergent thinking) and convergence on a single solution (convergent thinking) can lead financial professionals to create and choose the best interpretations for phenomena observed and how to best utilize the information going forward. Employees at any level in the organization, from newly hired staff to those in the executive ranks, can use metacognition to improve their critical assessment of results when analyzing data.

THINKING ABOUT THINKING

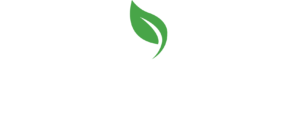

Metacognition refers to individuals’ ability to be aware, understand, and purposefully guide how to think about a problem (see “What Is Metacognition?”). It’s also been described as “thinking about thinking” or “knowing about knowing” and can lead to a more careful and focused analysis of information. Metacognition can be thought about broadly as a way to improve critical thinking and problem solving.

In their article “Training Auditors to Perform Analytical Procedures Using Metacognitive Skills,” R. David Plumlee, Brett Rixom, and Andrew Rosman evaluated how different types of thinking can be applied to a variety of problems, such as the results of analytical procedures, and how those types of thinking can help auditors arrive at the correct explanation for unexpected results that were found ( The Accounting Review , January 2015). The training methods they describe in their study, based on the psychological research examining metacognition, focus on applying divergent and convergent thinking.

While they employed settings most commonly encountered by staff in an audit firm, their approach didn’t focus on methods used solely by public accountants. Therefore, the results can be generalized to professionals who work with all types of financial and nonfinancial data. It’s particularly helpful for those conducting data analysis.

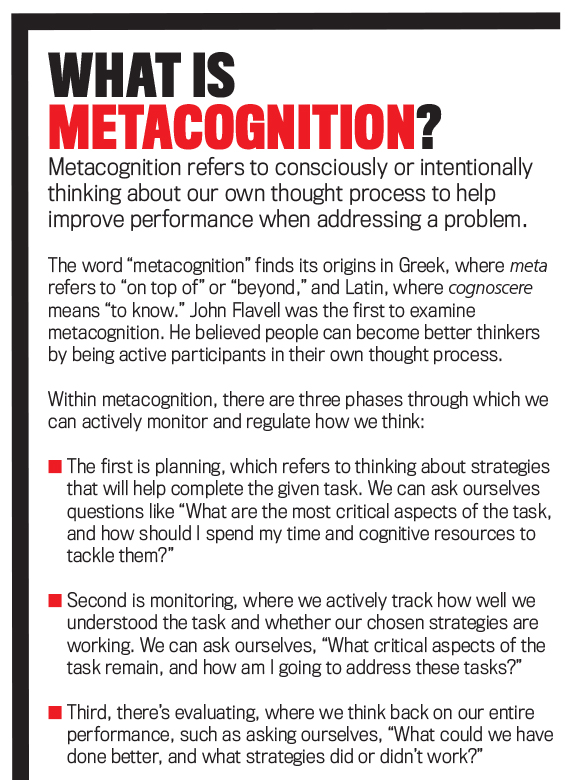

Their approach involved a sequential process of divergent thinking followed by convergent thinking. Divergent thinking refers to creating multiple reasons about what could be causing the surprising or unusual patterns encountered when analyzing data before a definitive rationale is used to inform what actions to take or strategy to use. Here’s an example of divergent thinking:

The customer satisfaction metric employed by RNO Company has increased steadily for the quarter, yet its sales numbers and revenue have declined steadily for the same period. Jill, a senior accountant, conducted ratio and trend analyses and found some of the results to be unusual. To apply divergent thinking, Jill would think of multiple potential reasons for this surprising result before removing any reason from consideration.

Convergent thinking is the process of finding the best explanation for the surprising results so that potential actions can be explored accordingly. The process consists of narrowing down the different reasons by ensuring the only reasons that are kept for consideration are ones that explain all of the surprising patterns seen in the results without explaining more than what is needed. In this way, actions can be taken to address the heart of any problems found instead of just the symptoms. On the other hand, if the surprising result is beneficial to an organization, it can make it easier to take the correct actions to replicate the benefit in other aspects of the business. Here’s an example of convergent thinking:

Washoe, Inc.’s customer satisfaction metric has increased steadily for the quarter, yet sales numbers and revenue have steadily declined for the same period. Roberto found this result to be surprising. After employing divergent thinking to identify 10 potential reasons for this result, such as “the reason that customers seem more satisfied is that the price of goods has been reduced, which also explains the reduction in sales revenue.” To apply convergent thinking, Roberto reviewed each reason that best fit. If the reason doesn’t explain the unusual results satisfactorily, then it will either be modified or discarded. For example, the reduced price of goods doesn’t explain all of the results—specifically, the decrease in units sold—so it needs to either be eliminated as a possible explanation or modified until it does explain all the results.

Exploring strategic or corrective actions based on reasons that completely explain the unusual results increases the chance of correctly addressing the actual issue behind the surprising result. Also, by making sure that the reason doesn’t contain extraneous details, unneeded actions can be avoided.

It’s important to note that a sequential process is required for these types of thinking to be most effective. When encountering a surprising or unexpected result during data analysis, accounting professionals must first focus strictly on divergent thinking—thinking about potential reasons—before using convergent thinking to choose a reason that best explains the surprising result. If convergent thinking is used before divergent thinking is completed, it can lead to reasons being picked simply because they came to mind right away.

LEARNING THE PROCESS

Improving divergent and convergent thinking can benefit employees at any level of an organization. Newer professionals who don’t have as much technical knowledge and experience to draw upon may be more likely to focus on the first explanation that comes to mind (“premature convergent thinking”) without fully considering all of the potential reasons for the surprising results. Experienced individuals such as CFOs and controllers have more technical knowledge and practical experience to rely on, but it’s possible these seasoned employees fall into habits and follow past patterns of thought without fully exploring potential causes for surprising results.

Instructing all accounting professionals on how to think about surprising results can help them have a more complete understanding of the issues at hand that will help guide actions taken in the future. It can lead to a more creative approach when analyzing information and ultimately to better problem solving.

When teaching employees to use divergent and convergent thinking, the goal is to get them to focus on what should be done once they identify information that suggests a surprising result has occurred. The first step is to learn how to properly use divergent thinking to create a set of plausible explanations more likely to contain the actual reason for the surprising results. There’s a three-step method that individuals can follow (see Table 1):

- Ask a broad question that reflects the goal you have: For instance, what is it about the current information that suggests a potential surprising event? Or what led to this event that can help predict future occurrences?

- Answer that question with a complete sentence: Be sure the answer includes a description of the information that suggests a potential surprising event.

- Turn the broad question into a creative challenge: Identify the plausible reasons that could have led to the indications of a surprising event.

Once employees have a good grasp of how to use divergent thinking, the next step is to instruct them in the proper use of convergent thinking, which involves choosing the best possible reason from the ones identified during the divergent thinking process. Potential reasons need to be narrowed down by removing or modifying those that either don’t fully explain the surprising results or that overexplain the results.

Two simple questions can help individuals screen each of the possible explanations generated in the divergent thinking process (see Table 2):

- Can I think of transactions or events that would be considered expected but are accounted for by my explanation?

- Can I think of transactions or events that aren’t accounted for by my explanation but are unusual?

The first question is designed for an individual to think about whether there are other events outside of the current issue that fit the explanation: “Does the explanation also address phenomena that aren’t related to or outside the scope of the surprising result that’s being studied?” If the answer is “yes,” then this is a case of overexplanation. Consider, for example, a scenario involving an increase in bad debts. Relaxing credit requirements may explain the increase, but they would also explain a growth in sales and falling employee morale due to working massive amounts of overtime to make products for sale.

The second question is designed to think about whether an explanation only accounts for part of the phenomenon being observed: “Does the explanation address only part of what’s being observed while leaving other important details unexplained?” If the answer is “yes,” then it’s an under-explanation. For example, consider a decline in sales. An economic downturn at the same time as the decline may be a possible explanation, but it might only be part of the problem. A drop in product quality or a drop in demand due to obsolescence could also be causing sales to decline.

If the answer to either screening question is “yes,” then the explanation needs to be discarded from consideration or modified to better address the concern. In the case of over-explanation, the reason is too general and may lead to action areas where none is needed while still not addressing the actual issue. For underexplanation, the reason is incomplete because it accounts for only a portion of the phenomenon observed, thus action may only address a symptom and not the actual root problem.

If the answer to both questions is “no,” then the explanation is viable. The chosen reason neither overexplains nor underexplains the issue at hand, making it more likely that the recommended solution or plan of action based on that reason will be more successful at addressing the actual cause of the issue.

Divergent and convergent thinking are two distinct processes that work in conjunction with each other to arrive at potential reasons for the results they observe. Yet, as previously noted, the two ways of thinking must be conducted separately and sequentially in order to obtain optimal results. Divergent thinking must be applied first in order to achieve a diverse set of potential reasons. This will maximize the probability of generating a feasible reason that explains the results correctly. After the set of potential reasons has been generated using the divergent thinking approach, convergent thinking should be used to methodically remove or modify the reasons that don’t fit with the surprising results.

If both divergent thinking and convergent thinking are done simultaneously, premature convergence can lead to a less-than-optimal reason being chosen, which may lead to taking the wrong course of action. Thus, it’s important with training to instruct employees in the use of both divergent thinking and convergent thinking and to use the types of thinking sequentially.

ORGANIZATIONAL TRAINING

Learning to apply divergent and convergent thinking can require a substantial time commitment. The process we’ve described here is designed to enhance critical thinking and problem-solving skills. It outlines a general approach that doesn’t provide specific guidance on the best methods to analyze data or complete a task but rather focuses on successful methods to think of a diverse set of reasons for any surprising results and then how to choose the best explanation for that result in order to be able to recommend the most appropriate actions or solutions.

Individuals can practice the approach we’ve described on their own, but each organization will likely have its own preferred way to approach the analyses. Plumlee, et al., used training modules in their study that could be employed in a concerted effort by a company, with supervisors training their employees. We estimate that a basic training session would take about two hours. Complete training with practice and feedback would require about four hours—which could grow longer with even more for intensive training.

One area where this training could be very effective in helping employees is data analytics. In the past decade, an increasing amount of accounting and financial work involves or relies on data analysis. Data availability has increased exponentially, and companies use or have developed software that generates sophisticated analytical results.

Typical data analysis procedures accounting professionals might be called on to perform include things such as ratio and trend analyses, which compare financial and nonfinancial data over time and against industry information to examine whether results achieved are in line with expectations for strategic actions. Additionally, analyses are forward-looking when performance measures examined are leading indicators.

In order to perform data analytics effectively, accounting professionals must exercise sufficient judgment to critically assess the implications of any surprising results that are found. The quality of judgments and understanding the best ways to conduct and interpret the information uncovered by data analytics have typically been a function of time spent on the job along with training. At the same time, however, it’s commonplace that many of these analyses are performed by newer professionals.

Training in metacognition will help these employees more effectively and creatively reach conclusions about what they’ve observed in their analysis. Since the method discussed provides general instruction, each organization can customize the approach to best fit its own operations, strategies, and goals. Implementing a training program can be worth the investment given the importance of critical thinking throughout the process of evaluating operating results. Avoiding potential failures with interpreting results that could be prevented would seem to warrant the consideration of metacognitive training.

About the Authors

November 2021

- Strategy, Planning & Performance

- Business Acumen & Operations

- Decision Analysis

- Operational Knowledge

Publication Highlights

Lessons from an Agile Product Owner

Explore more.

Copyright Footer Message

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Critical thinking is becoming increasingly important for accountants, as businesses look to you to provide insight, analysis and proposals to improve your, or your clients' business. This course explores critical thinking techniques and provides practical advice on how to use them to benefit the organisations you work with.

The critical thinking skills analysis that the students choose can be applied in a variety of situations. Thus it is vital for them to understand how the critical thinking skills analysis works. Accountants should always exercise sound moral judgment in all accounting activities. Accountants have the unique

Today, professionals with accounting training backgrounds must be able to apply creative solutions to problems that businesses are facing, helping them to keep up with competitors and improve the profitability of their business model. Employers increasingly value accounting professionals who can apply creative thinking skills and problem-solving capabilities in order to come up with solutions ...

There have been repeated calls for greater critical thinking ability among accounting graduates, and current changes in the profession require strong critical thinking earlier in an accountant's career (e.g., Gupta & Marshall, 2010).Despite these repeated calls, Pincus et al. (2017) point out that little educational progress has been made. To encourage and assist in a greater focus on ...

accounting students' critical thinking skills during each exam. This practice is similar to Springer and Borthick's suggestion (2004) to encourage practicing with business simulations (see the previous chapter). The starting point of the Challenge Problem approach thus is turning the

Responding to the new demands of accounting bodies and employer organizations, academics have been quick to come up with alternative instructional strategies. ... or the use of simulations to engage students more deeply in their own learning as well as to develop their creative and critical thinking skills (aims determined by the Accounting ...

Techniques for developing creative thinking skills in accounting education — free and easy to adapt to in-class, online and hybrid settings. Join. Home; ... & Smith, G. S. (1998). Alternative instructional strategies for creative and critical thinking in the accounting curriculum. Journal of Accounting Education, 16(2), 261-293. Available at ...

For many years, accounting education research has highlighted the need for students to develop stronger critical thinking skills. This need has become even more imperative as the accounting profession continues to transition, and entry-level accountants are expected to demonstrate stronger critical thinking skills earlier in their careers.

Whether working with financial statements, analyzing operational and nonfinancial information, implementing machine learning and AI processes, or carrying out many of their other varied responsibilities, accounting and finance professionals need to apply critical thinking skills to interpret the story behind the numbers.

focused on creative thought. Accounting "rules" are fundamentally invitations to the ... as new technologies and global realities work their way through the accounting profession, the demand for change in preparing accountants increases. ... To help develop their students' critical thinking skills, educators can use various approaches and ...