No Search Results

- Learn LaTeX in 30 minutes

This introductory tutorial does not assume any prior experience of L a T e X but, hopefully, by the time you are finished, you will not only have written your first L a T e X document but also acquired sufficient knowledge and confidence to take the next steps toward L a T e X proficiency.

- 1 What is L a T e X ?

- 2 Why learn L a T e X ?

- 3 Writing your first piece of L a T e X

- 4 The preamble of a document

- 5 Including title, author and date information

- 6 Adding comments

- 7 Bold, italics and underlining

- 8 Adding images

- 9 Captions, labels and references

- 10.1 Unordered lists

- 10.2 Ordered lists

- 11.1 Inline math mode

- 11.2 Display math mode

- 11.3 More complete examples

- 12.1 Abstracts

- 12.2 Paragraphs and new lines

- 12.3 Chapters and sections

- 13.1 Creating a basic table in L a T e X

- 13.2 Adding borders

- 13.3 Captions, labels and references

- 14 Adding a Table of Contents

- 15 Downloading your finished document

- 16.1 Loading packages

- 16.2 Finding information about packages: CTAN

- 16.3 Packages available on Overleaf: Introducing TeX Live

What is L a T e X ?

L a T e X (pronounced “ LAY -tek” or “ LAH -tek”) is a tool for typesetting professional-looking documents. However, LaTeX’s mode of operation is quite different to many other document-production applications you may have used, such as Microsoft Word or LibreOffice Writer: those “ WYSIWYG ” tools provide users with an interactive page into which they type and edit their text and apply various forms of styling. LaTeX works very differently: instead, your document is a plain text file interspersed with LaTeX commands used to express the desired (typeset) results. To produce a visible, typeset document, your LaTeX file is processed by a piece of software called a TeX engine which uses the commands embedded in your text file to guide and control the typesetting process, converting the LaTeX commands and document text into a professionally typeset PDF file. This means you only need to focus on the content of your document and the computer, via LaTeX commands and the TeX engine, will take care of the visual appearance (formatting).

Why learn L a T e X ?

Various arguments can be proposed for, or against, learning to use L a T e X instead of other document-authoring applications; but, ultimately, it is a personal choice based on preferences, affinities, and documentation requirements.

Arguments in favour of L a T e X include:

- support for typesetting extremely complex mathematics, tables and technical content for the physical sciences;

- facilities for footnotes, cross-referencing and management of bibliographies;

- ease of producing complicated, or tedious, document elements such as indexes, glossaries, table of contents, lists of figures;

- being highly customizable for bespoke document production due to its intrinsic programmability and extensibility through thousands of free add-on packages .

Overall, L a T e X provides users with a great deal of control over the production of documents which are typeset to extremely high standards. Of course, there are types of documents or publications where L a T e X doesn’t shine, including many “free form” page designs typically found in magazine-type publications.

One important benefit of L a T e X is the separation of document content from document style: once you have written the content of your document, its appearance can be changed with ease. Similarly, you can create a L a T e X file which defines the layout/style of a particular document type and that file can be used as a template to standardise authorship/production of additional documents of that type; for example, this allows scientific publishers to create article templates, in L a T e X , which authors use to write papers for submission to journals. Overleaf has a gallery containing thousands of templates , covering an enormous range of document types—everything from scientific articles, reports and books to CVs and presentations. Because these templates define the layout and style of the document, authors need only to open them in Overleaf—creating a new project—and commence writing to add their content.

Writing your first piece of L a T e X

The first step is to create a new L a T e X project. You can do this on your own computer by creating a new .tex file; alternatively, you can start a new project in Overleaf .

Let’s start with the simplest working example, which can be opened directly in Overleaf:

Open this example in Overleaf.

This example produces the following output:

You can see that L a T e X has automatically indented the first line of the paragraph, taking care of that formatting for you. Let’s have a closer look at what each part of our code does.

The first line of code, \documentclass{article} , declares the document type known as its class , which controls the overall appearance of the document. Different types of documents require different classes; i.e., a CV/resume will require a different class than a scientific paper which might use the standard L a T e X article class. Other types of documents you may be working on may require different classes such as book or report . To get some idea of the many L a T e X class types available, visit the relevant page on CTAN (Comprehensive TeX Archive Network) .

Having set the document class, our content, known as the body of the document, is written between the \begin{document} and \end{document} tags. After opening the example above, you can make changes to the text and, when finished, view the resulting typeset PDF by recompiling the document . To do this in Overleaf, simply hit Recompile , as demonstrated in this brief video clip:

Any Overleaf project can be configured to recompile automatically each time it is edited: click the small arrow next to the Recompile button and set Auto Compile to On , as shown in the following screengrab:

Having seen how to add content to our document, the next step is to give it a title. To do this, we must talk briefly about the preamble .

The preamble of a document

The screengrab above shows Overleaf storing a L a T e X document as a file called main.tex : the .tex file extension is, by convention, used when naming files containing your document’s LaTeX code.

The previous example showed how document content was entered after the \begin{document} command; however, everything in your .tex file appearing before that point is called the preamble , which acts as the document’s “setup” section. Within the preamble you define the document class (type) together with specifics such as languages to be used when writing the document; loading packages you would like to use (more on this later ), and it is where you’d apply other types of configuration.

A minimal document preamble might look like this:

where \documentclass[12pt, letterpaper]{article} defines the overall class (type) of document. Additional parameters, which must be separated by commas, are included in square brackets ( [...] ) and used to configure this instance of the article class; i.e., settings we wish to use for this particular article -class-based document.

In this example, the two parameters do the following:

- 12pt sets the font size

- letterpaper sets the paper size

Of course other font sizes, 9pt , 11pt , 12pt , can be used, but if none is specified, the default size is 10pt . As for the paper size, other possible values are a4paper and legalpaper . For further information see the article about page size and margins .

The preamble line

is an example of loading an external package (here, graphicx ) to extend L a T e X ’s capabilities, enabling it to import external graphics files. L a T e X packages are discussed in the section Finding and using L a T e X packages .

Including title, author and date information

Adding a title, author and date to our document requires three more lines in the preamble ( not the main body of the document). Those lines are:

- \title{My first LaTeX document} : the document title

- \thanks{Funded by the Overleaf team.} : can be added after the name of the author, inside the braces of the author command. It will add a superscript and a footnote with the text inside the braces. Useful if you need to thank an institution in your article.

- \date{August 2022} : you can enter the date manually or use the command \today to typeset the current date every time the document is compiled

With these lines added, your preamble should look something like this:

To typeset the title, author and date use the \maketitle command within the body of the document:

The preamble and body can now be combined to produce a complete document which can be opened in Overleaf:

Adding comments

LaTeX is a form of “program code”, but one which specializes in document typesetting; consequently, as with code written in any other programming language, it can be very useful to include comments within your document. A L a T e X comment is a section of text that will not be typeset or affect the document in any way—often used to add “to do” notes; include explanatory notes; provide in-line explanations of tricky macros or comment-out lines/sections of LaTeX code when debugging.

To make a comment in L a T e X , simply write a % symbol at the beginning of the line, as shown in the following code which uses the example above:

This example produces output that is identical to the previous LaTeX code which did not contain the comment.

- Bold, italics and underlining

Next, we will now look at some text formatting commands:

- Bold : bold text in LaTeX is typeset using the \textbf{...} command.

- Italics : italicised text is produced using the \textit{...} command.

- Underline : to underline text use the \underline{...} command.

The next example demonstrates these commands:

Another very useful command is \emph{ argument } , whose effect on its argument depends on the context. Inside normal text, the emphasized text is italicized, but this behaviour is reversed if used inside an italicized text—see the next example:

Open this \emph example in Overleaf.

- Note: some packages, such as Beamer , change the behaviour of the \emph command.

Adding images

In this section we will look at how to add images to a L a T e X document. Overleaf supports three ways to insert images:

- Copy and paste an image into Visual Editor or Code Editor .

- Use Code Editor to write LaTeX code that inserts a graphic.

Options 1 and 2 automatically generate the LaTeX code required to insert images, but here we introduce option 3—note that you will need to upload those images to your Overleaf project. The following example demonstrates how to include a picture:

Open this image example in Overleaf.

Importing graphics into a L a T e X document needs an add-on package which provides the commands and features required to include external graphics files. The above example loads the graphicx package which, among many other commands, provides \includegraphics{...} to import graphics and \graphicspath{...} to advise L a T e X where the graphics are located.

To use the graphicx package, include the following line in your Overleaf document preamble:

In our example the command \graphicspath{{images/}} informs L a T e X that images are kept in a folder named images , which is contained in the current directory:

The \includegraphics{universe} command does the actual work of inserting the image in the document. Here, universe is the name of the image file but without its extension.

- Although the full file name, including its extension, is allowed in the \includegraphics command, it’s considered best practice to omit the file extension because it will prompt L a T e X to search for all the supported formats.

- Generally, the graphic’s file name should not contain white spaces or multiple dots; it is also recommended to use lowercase letters for the file extension when uploading image files to Overleaf.

More information on L a T e X packages can be found at the end of this tutorial in the section Finding and using LaTeX packages .

Captions, labels and references

Images can be captioned, labelled and referenced by means of the figure environment, as shown below:

There are several noteworthy commands in the example:

- \includegraphics[width=0.75\textwidth]{mesh} : This form of \includegraphics instructs L a T e X to set the figure’s width to 75% of the text width—whose value is stored in the \textwidth command.

- \caption{A nice plot.} : As its name suggests, this command sets the figure caption which can be placed above or below the figure. If you create a list of figures this caption will be used in that list.

- \label{fig:mesh1} : To reference this image within your document you give it a label using the \label command. The label is used to generate a number for the image and, combined with the next command, will allow you to reference it.

- \ref{fig:mesh1} : This code will be substituted by the number corresponding to the referenced figure.

Images incorporated in a L a T e X document should be placed inside a figure environment, or similar, so that L a T e X can automatically position the image at a suitable location in your document.

Further guidance is contained in the following Overleaf help articles:

- Positioning of Figures

- Inserting Images

Creating lists in L a T e X

You can create different types of list using environments , which are used to encapsulate the L a T e X code required to implement a specific typesetting feature. An environment starts with \begin{ environment-name } and ends with \end{ environment-name } where environment-name might be figure , tabular or one of the list types: itemize for unordered lists or enumerate for ordered lists.

Unordered lists

Unordered lists are produced by the itemize environment. Each list entry must be preceded by the \item command, as shown below:

You can also open this larger Overleaf project which demonstrates various types of L a T e X list.

Ordered lists

Ordered lists use the same syntax as unordered lists but are created using the enumerate environment:

As with unordered lists, each entry must be preceded by the \item command which, here, automatically generates the numeric ordered-list label value, starting at 1.

For further information you can open this larger Overleaf project which demonstrates various types of L a T e X list or visit our dedicated help article on L a T e X lists , which provides many more examples and shows how to create customized lists.

Adding math to L a T e X

One of the main advantages of L a T e X is the ease with which mathematical expressions can be written. L a T e X provides two writing modes for typesetting mathematics:

- inline math mode used for writing formulas that are part of a paragraph

- display math mode used to write expressions that are not part of a text or paragraph and are typeset on separate lines

Inline math mode

Let’s see an example of inline math mode:

To typeset inline-mode math you can use one of these delimiter pairs: \( ... \) , $ ... $ or \begin{math} ... \end{math} , as demonstrated in the following example:

Display math mode

Equations typeset in display mode can be numbered or unnumbered, as in the following example:

To typeset display-mode math you can use one of these delimiter pairs: \[ ... \] , \begin{displaymath} ... \end{displaymath} or \begin{equation} ... \end{equation} . Historically, typesetting display-mode math required use of $$ characters delimiters, as in $$ ... display math here ... $$ , but this method is no longer recommended : use LaTeX’s delimiters \[ ... \] instead.

More complete examples

The following examples demonstrate a range of mathematical content typeset using LaTeX.

The next example uses the equation* environment which is provided by the amsmath package, so we need to add the following line to our document preamble:

For further information on using amsmath see our help article .

The possibilities with math in L a T e X are endless so be sure to visit our help pages for advice and examples on specific topics:

- Mathematical expressions

- Subscripts and superscripts

- Brackets and Parentheses

- Fractions and Binomials

- Aligning Equations

- Spacing in math mode

- Integrals, sums and limits

- Display style in math mode

- List of Greek letters and math symbols

- Mathematical fonts

Basic document structure

Next, we explore abstracts and how to partition a L a T e X document into different chapters, sections and paragraphs.

Scientific articles usually provide an abstract which is a brief overview/summary of their core topics, or arguments. The next example demonstrates typesetting an abstract using L a T e X ’s abstract environment:

- Paragraphs and new lines

With the abstract in place, we can begin writing our first paragraph. The next example demonstrates:

- how a new paragraph is created by pressing the "enter" key twice, ending the current line and inserting a subsequent blank line;

- how to start a new line without starting a new paragraph by inserting a manual line break using the \\ command, which is a double backslash; alternatively, use the \newline command.

The third paragraph in this example demonstrates use of the commands \\ and \newline :

Note how L a T e X automatically indents paragraphs—except immediately after document headings such as section and subsection— as we will see .

New users are advised that multiple \\ or \newline s should not used to “simulate” paragraphs with larger spacing between them because this can interfere with L a T e X ’s typesetting algorithms. The recommended method is to continue using blank lines for creating new paragraphs, without any \\ , and load the parskip package by adding \usepackage{parskip} to the preamble.

Further information on paragraphs can be found in the following articles:

- How to change paragraph spacing in LaTeX

- LaTeX Error: There's no line here to end provides additional advice and guidance on using \\ .

Chapters and sections

Longer documents, irrespective of authoring software, are usually partitioned into parts, chapters, sections, subsections and so forth. LaTeX also provides document-structuring commands but the available commands, and their implementations (what they do), can depend on the document class being used. By way of example, documents created using the book class can be split into parts, chapters, sections, subsections and so forth but the letter class does not provide (support) any commands to do that.

This next example demonstrates commands used to structure a document based on the book class:

The names of sectioning commands are mostly self-explanatory; for example, \chapter{First Chapter} creates a new chapter titled First Chapter , \section{Introduction} produces a section titled Introduction , and so forth. Sections can be further divided into \subsection{...} and even \subsubsection{...} . The numbering of sections, subsections etc. is automatic but can be disabled by using the so-called starred version of the appropriate command which has an asterisk (*) at the end, such as \section*{...} and \subsection*{...} .

Collectively , LaTeX document classes provide the following sectioning commands, with specific classes each supporting a relevant subset:

- \part{part}

- \chapter{chapter}

- \section{section}

- \subsection{subsection}

- \subsubsection{subsubsection}

- \paragraph{paragraph}

- \subparagraph{subparagraph}

In particular, the \part and \chapter commands are only available in the report and book document classes.

Visit the Overleaf article article about sections and chapters for further information about document-structure commands.

Creating tables

Overleaf provides three options to create tables:

- Using the Insert Table button in the Visual Editor (or Code Editor ) toolbar.

- Copying and pasting a table from another document while using Visual Editor .

- Writing the LaTeX code for the table in Code Editor.

If you’re new to LaTeX, using the toolbar in Visual Editor (option 1) is a great way to get started—you can switch between Visual Editor and Code Editor to see the code behind the table.

Here, we focus on option 3—the most flexible method for creating tables—and provide examples that demonstrate how to create tables in LaTeX, including the addition of lines (rules) and captions. As you gain experience, take a look at our detailed guidance on how to create tables using LaTeX .

Creating a basic table in L a T e X

We start with an example showing how to typeset a basic table:

The tabular environment is the default L a T e X method to create tables. You must specify a parameter to this environment, in this case {c c c} which advises L a T e X that there will be three columns and the text inside each one must be centred. You can also use r to right-align the text and l to left-align it. The alignment symbol & is used to demarcate individual table cells within a table row. To end a table row use the new line command \\ . Our table is contained within a center environment to make it centred within the text width of the page.

Adding borders

The tabular environment supports horizontal and vertical lines (rules) as part of the table:

- to add horizontal rules, above and below rows, use the \hline command

- to add vertical rules, between columns, use the vertical line parameter |

In this example the argument is {|c|c|c|} which declares three (centred) columns each separated by a vertical line (rule); in addition, we use \hline to place a horizontal rule above the first row and below the final row:

Here is a further example:

You can caption and reference tables in much the same way as images. The only difference is that instead of the figure environment, you use the table environment.

Adding a Table of Contents

Creating a table of contents is straightforward because the command \tableofcontents does almost all the work for you:

Sections, subsections and chapters are automatically included in the table of contents. To manually add entries, such as an unnumbered section, use the command \addcontentsline as shown in the example.

Downloading your finished document

The following brief video clip shows how to download your project’s source code or the typeset PDF file:

More information can be found in the Overleaf help article Exporting your work from Overleaf .

Finding and using LaTeX packages

L a T e X not only delivers significant typesetting capabilities but also provides a framework for extensibility through the use of add-on packages . Rather than attempting to provide commands and features that “try to do everything”, L a T e X is designed to be extensible , allowing users to load external bodies of code (packages) that provide more specialist typesetting capabilities or extend L a T e X ’s built-in features—such as typesetting tables. As observed in the section Adding images , the graphicx package extends L a T e X by providing commands to import graphics files and was loaded (in the preamble) by writing

Loading packages

As noted above, packages are loaded in the document preamble via the \usepackage command but because (many) L a T e X packages provide a set of options , which can be used to configure their behaviour, the \usepackage command often looks like this:

The square brackets “ [...] ” inform L a T e X which set of options should be applied when it loads somepackage . Within the set of options requested by the user, individual options, or settings, are typically separated by a comma; for example, the geometry package provides many options to configure page layout in L a T e X , so a typical use of geometry might look like this:

The geometry package is one example of a package written and contributed by members of the global L a T e X community and made available, for free, to anyone who wants to use it.

If a L a T e X package does not provide any options, or the user wants to use the default values of a package’s options, it would be loaded like this:

When you write \usepackage[...]{somepackage} L a T e X looks for a corresponding file called somepackage .sty , which it needs to load and process—to make the package commands available and execute any other code provided by that package. If L a T e X cannot find somepackage .sty it will terminate with an error, as demonstrated in the following Overleaf example:

Open this error-generating example on Overleaf

Finding information about packages: CTAN

Packages are distributed through the Comprehensive TeX Archive Network , usually referred to as CTAN, which, at the time of writing, hosts 6287 packages from 2881 contributors. CTAN describes itself as

... a set of Internet sites around the world that offer TEX-related material for download.

You can browse CTAN to look for useful packages; for example:

- alphabetically (useful if you know the package name)

You can also use the search facility (at the top of the page).

Packages available on Overleaf: Introducing TeX Live

Once per year a (large) subset of packages hosted on CTAN, plus L a T e X -related fonts and other software, is collated and distributed as a system called TeX Live , which can be used to install your own (local) LaTeX setup. In fact, Overleaf’s servers also use TeX Live and are updated when a new version of TeX Live is released. Overleaf’s TeX Live updates are not immediate but take place a few months post-release, giving us time to perform compatibility tests of the new TeX Live version with the thousands of templates contained in our gallery . For example, here is our TeX Live 2022 upgrade announcement .

Although TeX Live contains a (large) subset of CTAN packages it is possible to find an interesting package, such as igo for typesetting Go diagrams , which is hosted on CTAN but not included in (distributed by) TeX Live and thus unavailable on Overleaf. Some packages hosted on CTAN are not part of TeX Live due to a variety of reasons: perhaps a package is obsolete, has licensing problems, is extremely new (recently uploaded) or has platform dependencies, such as working on Windows but not Linux.

New packages, and updates to existing ones, are uploaded to CTAN all year round but updates to TeX Live are distributed annually; consequently, packages contained in the current version of TeX Live will not be as up-to-date as those hosted on CTAN. Because Overleaf’s servers use TeX Live it is possible that packages installed on our servers—i.e., ones available to our users—might not be the very latest versions available on CTAN but, generally, this is unlikely to be problematic.

- Documentation Home

Overleaf guides

- Creating a document in Overleaf

- Uploading a project

- Copying a project

- Creating a project from a template

- Using the Overleaf project menu

- Including images in Overleaf

- Exporting your work from Overleaf

- Working offline in Overleaf

- Using Track Changes in Overleaf

- Using bibliographies in Overleaf

- Sharing your work with others

- Using the History feature

- Debugging Compilation timeout errors

- How-to guides

- Guide to Overleaf’s premium features

LaTeX Basics

- Creating your first LaTeX document

- Choosing a LaTeX Compiler

Mathematics

- Aligning equations

- Using the Symbol Palette in Overleaf

Figures and tables

- Positioning Images and Tables

- Lists of Tables and Figures

- Drawing Diagrams Directly in LaTeX

- TikZ package

References and Citations

- Bibliography management with bibtex

- Bibliography management with natbib

- Bibliography management with biblatex

- Bibtex bibliography styles

- Natbib bibliography styles

- Natbib citation styles

- Biblatex bibliography styles

- Biblatex citation styles

- Multilingual typesetting on Overleaf using polyglossia and fontspec

- Multilingual typesetting on Overleaf using babel and fontspec

- International language support

- Quotations and quotation marks

Document structure

- Sections and chapters

- Table of contents

- Cross referencing sections, equations and floats

- Nomenclatures

- Management in a large project

- Multi-file LaTeX projects

- Lengths in L a T e X

- Headers and footers

- Page numbering

- Paragraph formatting

- Line breaks and blank spaces

- Text alignment

- Page size and margins

- Single sided and double sided documents

- Multiple columns

- Code listing

- Code Highlighting with minted

- Using colours in LaTeX

- Margin notes

- Font sizes, families, and styles

- Font typefaces

- Supporting modern fonts with X Ǝ L a T e X

Presentations

- Environments

Field specific

- Theorems and proofs

- Chemistry formulae

- Feynman diagrams

- Molecular orbital diagrams

- Chess notation

- Knitting patterns

- CircuiTikz package

- Pgfplots package

- Typesetting exams in LaTeX

- Attribute Value Matrices

Class files

- Understanding packages and class files

- List of packages and class files

- Writing your own package

- Writing your own class

Advanced TeX/LaTeX

- In-depth technical articles on TeX/LaTeX

Get in touch

Have you checked our knowledge base ?

Message sent! Our team will review it and reply by email.

Email:

- Paraphrasing Tools

- Referencing Tools

- proofreading

- Research Methodology

- Who we are?

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Affiliate Disclosure

- Terms and Conditions

- PhD Positions

- Work with us

- PhD Motivation Quotes

- Web Stories

How to Write a Thesis in LaTeX: A Complete Guide

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: introduction to latex, 1.1 what is latex.

LaTeX is a high-quality typesetting system used for creating scientific and technical documents. Unlike word processors like Microsoft Word, LaTeX allows for greater control over document structure, formatting, and layout. This makes it an ideal choice for writing academic theses, research papers, and dissertations.

LaTeX (pronounced Lay-tech or Lah-tech) is a powerful document preparation system widely used in academia, especially for writing scientific papers, theses, and technical documents. Unlike standard word processors, LaTeX separates the content of a document from its formatting. This allows users to focus on writing without worrying too much about the visual design.

LaTeX is based on TeX, a typesetting system developed by Donald Knuth in the late 1970s. It is particularly well-suited for producing documents that include:

- Complex mathematical equations

- References and citations

- Large sections of structured text such as chapters, sections, and subsections

- High-quality figures and tables

While LaTeX does have a steeper learning curve compared to traditional word processors like Microsoft Word, it provides unparalleled control over formatting, which is why it remains popular in research fields like physics, mathematics, computer science, engineering, and linguistics.

1.2 Why Use LaTeX for Thesis Writing?

LaTeX provides several benefits for writing a thesis:

- Consistency in Formatting: LaTeX automatically handles most aspects of document formatting, ensuring consistency throughout your document. This is particularly helpful when writing a long and complex document like a thesis.

- Automated Table of Contents and Lists: LaTeX will automatically generate and update your table of contents, list of figures, and list of tables as you add sections, figures, and tables.

- Precise Control of Layout: You have full control over page layout, margins, fonts, and spacing. If your university has specific formatting guidelines, LaTeX allows you to easily comply with them.

- Seamless Citations and References: With the help of BibTeX (or BibLaTeX), LaTeX manages all your citations, bibliographies, and references with ease, ensuring that they are correctly formatted.

- Excellent Mathematical Typesetting: If your thesis involves complex equations or mathematics, LaTeX is unmatched in its ability to produce professional-looking mathematical content.

- Scalability: LaTeX is designed for large documents, allowing you to organize your thesis into multiple files and compile them into a single, coherent document. This is much easier to manage than dealing with a single large word processor file.

1.3 Challenges of LaTeX

- Learning Curve: LaTeX’s syntax can be overwhelming for beginners, especially if you are accustomed to WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get) editors.

- Customization: While LaTeX offers extensive customization, it can take time to learn how to tweak and fine-tune your document’s appearance.

However, the time invested in learning LaTeX is well worth it, as it simplifies the task of formatting and ensures a polished, professional document.

1.4 How LaTeX Works

LaTeX documents are written in plain text files with the extension .tex. Instead of directly formatting the text as you write (like in a word processor), you use a set of commands and tags to define how the document should be formatted. For example, to create a section heading, you write:

When you compile the .tex file, LaTeX processes the commands and generates a beautifully formatted document (usually in PDF format).

1.4.1 The LaTeX Workflow:

- Write the content of your document in a .tex file using LaTeX commands.

- Compile the .tex file using a LaTeX engine (like pdflatex) to generate a PDF or other desired output format.

- View and edit the generated PDF and go back to your .tex file to make necessary adjustments.

1.5 The Structure of a Basic LaTeX Document

A LaTeX document consists of two main parts:

- The Preamble : This is where you define the overall document structure, including settings for margins, fonts, and other global parameters. It’s also where you load any additional LaTeX packages.

- The Document Body : This contains the actual content of your thesis, including chapters, sections, figures, tables, and equations.

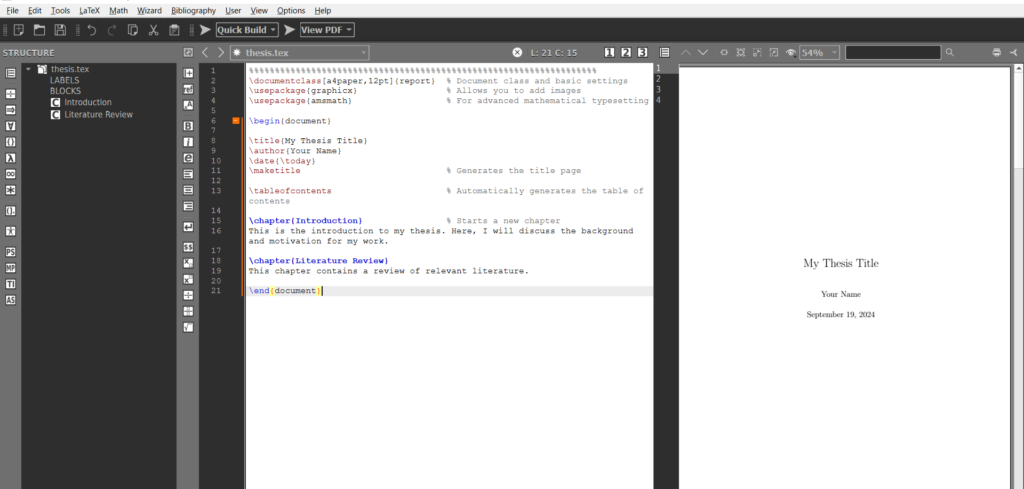

Here’s an example of a simple LaTeX document:

Explanation of the Key Commands:

- \documentclass{} : Specifies the document class. In this case, we are using the report class, which is ideal for theses.

- \usepackage{} : Adds extra functionality to LaTeX (e.g., graphicx for images, amsmath for advanced math typesetting).

- \begin{document} : Signals the start of the document body.

- \title , \author , and \date : Define the title page content.

- \maketitle : Generates the title page.

- \tableofcontents : Creates the table of contents based on the chapters and sections in the document.

- \chapter{} : Defines a new chapter.

- \end{document} : Signals the end of the document.

When you compile this .tex file, LaTeX will automatically generate a well-formatted PDF containing a title page, table of contents, and the first two chapters.

1.6 How LaTeX Handles Formatting

One of LaTeX’s greatest strengths is its ability to automatically handle formatting, so you don’t need to worry about adjusting font sizes, margins, or spacing manually. For example:

- Headings : LaTeX will automatically number chapters, sections, and subsections.

- Equations : Mathematical equations are formatted professionally, and LaTeX ensures that they are properly aligned.

- Tables and Figures : LaTeX makes it easy to position figures and tables, and automatically adjusts their layout to avoid overlapping with text.

With LaTeX, formatting is not a manual task. Instead, you define the overall structure and let LaTeX handle the rest.

1.7 Common Uses of LaTeX in Thesis Writing

- Mathematical and Scientific Writing : LaTeX is widely used in academic fields that require precise typesetting of complex mathematical equations.

- Long Documents : LaTeX excels at handling large, multi-chapter documents like theses and dissertations.

- Figures and Tables : LaTeX provides advanced capabilities for inserting and managing figures and tables, including the ability to generate lists of figures and tables.

- Bibliographies and Citations : LaTeX integrates well with bibliography management tools like BibTeX, making it easy to manage large numbers of references and citations.

1.8 Getting Started with LaTeX

Before you start writing your thesis in LaTeX, you need to install a LaTeX distribution and a text editor. The most commonly used LaTeX distributions are TeX Live and MiKTeX , while popular LaTeX editors include TeXworks , Texmaker , and Overleaf (a cloud-based LaTeX editor).

Once your LaTeX environment is set up, you can start writing your thesis by creating a .tex file and compiling it to produce a PDF.

Chapter 2: Setting Up Your LaTeX Environment

2.1 downloading and installing latex.

Before you can start writing your thesis in LaTeX, the first step is to set up your LaTeX environment. This involves installing a LaTeX distribution and a text editor where you will write your code.

2.1.1 Choosing a LaTeX Distribution

A LaTeX distribution is a bundle of programs and files that are needed to compile LaTeX documents into readable formats like PDF. The most commonly used distributions are:

- TeX Live (Recommended for all platforms: Windows, macOS, and Linux)

- MiKTeX (Primarily for Windows and macOS users)

2.1.2 TeX Live

TeX Live is a comprehensive distribution that works across platforms and is highly recommended for its stability and features. It includes all the tools you need to compile LaTeX documents into different formats, including PDF. You can download TeX Live from its official website:

- For Windows : TeX Live for Windows

- For macOS : TeX Live for macOS

- For Linux : You can install TeX Live via your package manager ( sudo apt-get install texlive-full for Ubuntu).

2.1.2 MiKTeX

MiKTeX is another popular LaTeX distribution that is user-friendly and frequently updated. It allows you to install additional packages on-the-fly, making it convenient for users who might need various LaTeX features later. You can download MiKTeX from its official website:

- MiKTeX for Windows/macOS : MiKTeX Download

Once downloaded, follow the installation prompts to install either distribution. After installation, your system will be ready to compile LaTeX documents.

2.2 Setting Up an Integrated Development Environment (IDE)

While you can technically write LaTeX code in any plain text editor (like Notepad or TextEdit), using an Integrated Development Environment (IDE) specifically designed for LaTeX will make your workflow smoother and more efficient. IDEs often include features like syntax highlighting, error checking, and one-click compilation to generate your PDF document.

2.2.1 Popular LaTeX Editors

Here are some of the most widely used LaTeX editors:

Overleaf (Online Cloud-Based Editor)

- Overleaf is a popular cloud-based LaTeX editor that allows you to write and compile LaTeX documents entirely online. It is ideal for collaborative projects, as multiple users can edit the same document in real-time.

- Pros : No installation needed, easy collaboration, automatic saving, large community.

- Cons : Requires internet connection.

Website : Overleaf

TeXworks (Offline Editor)

- TeXworks is a simple, easy-to-use LaTeX editor that comes bundled with most LaTeX distributions, including TeX Live and MiKTeX.

- Pros : Lightweight, straightforward interface, good for beginners.

- Cons : Limited advanced features compared to other editors.

Website : TeXworks

- Texmaker is a cross-platform LaTeX editor with a wide range of features, including PDF viewing, spell-checking, and code folding. It offers an integrated LaTeX development environment.

- Pros : Feature-rich, built-in PDF viewer, cross-platform (Windows, macOS, Linux).

- Cons : Slightly more complex for beginners.

Website : Texmaker

Visual Studio Code (VSCode) with LaTeX Workshop Extension

- VSCode is a highly customizable code editor, and with the LaTeX Workshop extension, it becomes a powerful LaTeX IDE.

- Pros : Great for users familiar with code editors, highly customizable, built-in terminal.

- Cons : Slightly steeper learning curve for beginners.

Website : Visual Studio Code

2.3 Writing Your First LaTeX Document

Now that your LaTeX environment is set up, let’s dive into writing your first LaTeX document. The basic structure of any LaTeX document consists of a preamble and a body.

2.3.1 Basic Structure of a LaTeX Document

- Preamble : This section defines the overall structure and style of the document. It is where you specify the document class, load necessary packages, and define global formatting options.

- Document Body : This is where the actual content (such as chapters, sections, text, and images) is written.

Here is a step-by-step guide to creating a simple LaTeX document:

- Open your LaTeX editor (Overleaf, TeXworks, or another).

- Create a new file and save it as thesis.tex .

- Write the following basic LaTeX code :

- \documentclass[a4paper,12pt]{report} : Defines the document class as a report with A4-sized paper and a font size of 12pt. The report class is suitable for writing a thesis.

- \usepackage{graphicx} : Imports the graphicx package, which allows you to add images to your document.

- \usepackage{amsmath} : Imports the amsmath package, enabling advanced mathematical typesetting.

- \maketitle : Generates the title page using the information provided by \title{} , \author{} , and \date{} .

- \tableofcontents : Automatically generates a table of contents based on the chapters, sections, and subsections in your document.

- \chapter{} : Creates a new chapter.

- \section{} : Creates a new section within a chapter.

- \subsection{} : Creates a subsection within a section.

- \end{document} : Marks the end of the LaTeX document.

2.3.2 Compiling the LaTeX Document

After writing your LaTeX code, the next step is to compile it and generate a PDF. The compilation process converts your .tex file into a PDF format that you can view and share.

To compile the document:

- In Overleaf , simply click the “Recompile” button, and the PDF will automatically be generated and displayed on the right.

- In TeXworks or Texmaker , you can click the green “Play” or “Compile” button to generate the PDF.

- In VSCode with the LaTeX Workshop extension, use the command Ctrl + Alt + B to compile the document.

Once compiled, you will have a neatly formatted PDF containing a title page, table of contents, and the first two chapters of your thesis.

2.4 Packages in LaTeX

LaTeX is highly modular, and you can add extra functionality to your documents by using packages. Packages are like plugins that extend the core functionality of LaTeX, allowing you to customize your document to meet specific needs.

2.4.1 Commonly Used LaTeX Packages

Here are some of the most useful LaTeX packages for writing a thesis:

- graphicx : Allows you to include images in your document.

- amsmath : Enhances LaTeX’s mathematical capabilities, adding support for more complex equations.

- geometry : Lets you customize page layout, margins, and paper size.

- setspace : Enables you to control line spacing (e.g., single, one-and-a-half, or double spacing).

- hyperref : Adds clickable links to your table of contents, references, and URLs.

To include a package in your LaTeX document, simply add the \usepackage{} command in the preamble:

2.5 Testing the Setup

Now that you’ve written and compiled your first LaTeX document, it’s time to test your setup by experimenting with different LaTeX commands and packages. Try adding new chapters, sections, and even images or equations to see how LaTeX handles them.

For example, add an image to your document using the graphicx package:

You can also explore formatting text, adding lists, or experimenting with mathematical equations using amsmath .

Chapter 3: Document Structure and Formatting in LaTeX

3.1 understanding document classes.

In LaTeX, the overall structure and formatting of your document are controlled by the document class . A document class determines how different elements—like sections, figures, tables, and references—are formatted.

When writing a thesis, you will typically use the report or book class. The choice of document class affects the layout and style of your document.

3.1.1 Common Document Classes

- Pros : Simple and easy to work with.

- Cons : Not designed for long documents with chapters.

- Pros : Allows chapters and structured content.

- Cons : Less sophisticated than the book class for very large documents.

- Pros : Comprehensive support for different sections, parts, and chapters.

- Cons : Slightly more complex than the report class.

- thesis (Custom Classes): Some institutions provide their own LaTeX class, typically named thesis.cls , that formats your document according to specific university requirements. Always check if your institution has such a class file.

3.2 Structuring a Thesis Document

A well-organized thesis document typically consists of various chapters, sections, subsections, and appendices. LaTeX makes it easy to structure your document hierarchically.

3.2.1 Chapters, Sections, and Subsections

A thesis often contains multiple chapters, each divided into sections and subsections. Here’s how you can define chapters, sections, and subsections in LaTeX:

Hierarchy Overview:

- \chapter{} : Top-level division (used in report and book classes).

- \section{} : Major section of a chapter.

- \subsection{} : Subdivision of a section.

- \subsubsection{} : Subdivision of a subsection.

You can also add paragraphs or subparagraphs for finer divisions if necessary:

3.3 Formatting Your Thesis

LaTeX provides powerful commands to control the formatting of text, paragraphs, lists, and other elements in your thesis. This ensures that your document not only follows academic standards but also remains aesthetically appealing.

3.3.1 Fonts and Font Sizes

You can easily change the font size of specific sections or the entire document. LaTeX supports various font sizes, ranging from tiny ( \tiny ) to very large ( \Huge ).

To change the font size of the entire document, modify the \documentclass options:

To change the font size of specific text, you can use:

Other available font sizes include \tiny , \scriptsize , \footnotesize , \normalsize , \large , \Large , \LARGE , and \Huge .

3.3.2 Line Spacing

You may want to adjust the line spacing in your thesis for readability or to meet institutional requirements. The setspace package makes this easy:

You can also adjust spacing for specific parts of the document:

3.4 Page Layout

LaTeX allows you to customize the layout of your pages, including margins, headers, footers, and page numbering. The geometry package is particularly useful for adjusting page margins.

3.4.1 Setting Margins

The geometry package allows you to control the margins of your document. Here’s an example of how to set 1-inch margins on all sides:

You can also set different margins for different parts of the document:

3.4.2 Headers and Footers

The fancyhdr package enables you to customize headers and footers, including adding page numbers and section titles.

To use the package:

With this code, each page will display the current chapter in the header and the page number in the footer.

3.5 Managing Long Documents

A thesis can become a lengthy and complex document, but LaTeX helps you manage large projects effectively by allowing you to break your document into smaller files.

3.5.1 Using \input{} and \include{}

When working on a large document like a thesis, it’s a good idea to split each chapter into separate .tex files and compile them into a single document.

Here’s how to do it:

- Create separate files for each chapter (e.g., chapter1.tex , chapter2.tex ).

- In your main file (e.g., thesis.tex ), use the \input{} or \include{} commands to include these files:

The \include{} command is ideal for long documents because it skips the compilation of files you aren’t currently working on, speeding up the process. The \input{} command is more suited for shorter or simpler files.

3.5.2 Table of Contents

LaTeX automatically generates a table of contents based on the chapters, sections, and subsections in your document. Simply add the following command where you want the table of contents to appear:

Every time you compile the document, the table of contents will update automatically.

3.6 Including Figures and Tables

LaTeX makes it easy to include figures and tables in your thesis, with options for labeling and referencing them throughout the document.

3.6.1 Adding Figures

To include an image in your document, use the graphicx package and the \includegraphics{} command. Make sure the image file is in the same directory as your .tex file, or provide the full path to the image.

This will insert an image with a caption, and you can reference it later using the label:

3.6.2 Creating Tables

LaTeX allows you to create neat tables with the tabular environment:

Like figures, tables can also be labeled and referenced later:

Chapter 4: Advanced Document Features in LaTeX

4.1 creating cross-references.

One of the most powerful features of LaTeX is the ability to easily create cross-references for sections, figures, tables, equations, and other elements in your document. These references automatically update as you modify the document, ensuring accuracy.

4.1.1 Referencing Sections and Subsections

To reference a section or subsection, you first need to label it with the \label{} command. Then, you can refer to that section anywhere in the document using \ref{} .

4.1.2 Referencing Figures and Tables

When you add figures or tables, it’s good practice to label them and reference them later in the text:

Similarly, for tables:

4.1.3 Hyperlinks with hyperref

The hyperref package allows you to create clickable hyperlinks within your document. It’s especially useful when generating a PDF, as clicking the link will jump to the corresponding section, figure, or table.

To include it in your document:

Now, your references will automatically become clickable links in the PDF.

For external links:

4.2 Citations and Bibliography

Citing references and creating a bibliography is a crucial part of any academic thesis. LaTeX offers a wide range of citation styles, allowing you to manage references using tools like BibTeX or biblatex .

4.2.1 Using BibTeX for Managing References

BibTeX is a tool that helps you manage and format your bibliography in LaTeX. You create a .bib file, which stores all your references, and then cite these references in your LaTeX document.

- Create a .bib file :

- Include the .bib file in your LaTeX document :

- Cite the reference in your text :

After compiling the document, LaTeX will automatically generate a formatted bibliography.

4.2.2 Using biblatex

biblatex offers more flexibility and customization for your bibliography compared to BibTeX . You can use it as follows:

- Load the package :

- Cite in your document :

- Print the bibliography :

4.3 Mathematical Equations and Symbols

LaTeX is widely recognized for its powerful handling of mathematical equations, symbols, and notations. This makes it the preferred tool for technical and scientific writing.

4.3.1 Inline Equations

For short equations that appear within the text, you can use inline math mode by enclosing the equation in dollar signs:

4.3.2 Display Equations

For larger equations that need to be centered and stand on their own, you can use the equation environment:

4.3.3 Mathematical Symbols

LaTeX supports an extensive set of symbols, including Greek letters and operators. Here are a few common ones:

- Greek Letters: $\alpha$, $\beta$, $\gamma$, $\delta$, $\lambda$

- Mathematical Operators: $\sum$, $\prod$, $\int$, $\frac{a}{b}$

- Set Symbols: $\in$, $\cup$, $\cap$, $\subset$

The amsmath package provides even more advanced features for handling equations:

4.4 Lists in LaTeX

Lists are an essential element in any document, helping to organize information into bullets or numbered points. LaTeX provides several list environments to meet different needs.

4.4.1 Itemized Lists

An itemized list creates a bulleted list:

This will generate:

- Second item

4.4.2 Enumerated Lists

An enumerated list creates a numbered list:

4.4.3 Descriptive Lists

A descriptive list allows you to define both terms and their descriptions:

4.5 Footnotes and Endnotes

Footnotes and endnotes are helpful for providing additional information without interrupting the flow of the main text.

4.5.1 Adding Footnotes

You can add footnotes anywhere in the document using the \footnote{} command:

4.5.2 Customizing Footnotes

If you want to change the numbering style of the footnotes, you can use:

4.6 Appendices

Appendices are used to include supplementary material that is important but not part of the main body of the text. LaTeX makes it easy to add appendices.

4.6.1 Creating Appendices

To create appendices in LaTeX, you simply use the \appendix command, which modifies the chapter and section numbering:

This will create a new appendix section, and chapters within the appendix will be labeled alphabetically (e.g., Appendix A, Appendix B).

Chapter 5: Customizing Your LaTeX Thesis

5.1 customizing the title page.

The title page is one of the most important parts of your thesis, as it contains essential information like your name, the thesis title, and your institution. You can easily create a custom title page in LaTeX by using the title , author , and date commands, but many institutions have specific formatting requirements, so customization is often necessary.

5.1.1 Basic Title Page

A simple title page can be created using the \maketitle command. You define the title, author, and date at the beginning of your document:

This will generate a basic title page with the title, author name, and date centered on the page.

5.1.2 Customizing the Title Page Layout

To fully customize the layout of the title page, you can bypass the \maketitle command and create the title page manually using various LaTeX commands for positioning, fonts, and spacing:

In this example, the title is enlarged using \Huge and \textbf{} for bold text. You can adjust the vertical spacing with brackets like [1.5cm] or [1cm] to control the appearance.

5.1.3 Adding Logos or Images

If your institution requires a logo on the title page, you can use the graphicx package to insert an image:

This inserts a logo above the thesis title and positions it using the \centering and \includegraphics[] commands. You can adjust the width of the image and the spacing around it.

5.2 Customizing Fonts and Styles

LaTeX offers a variety of font options to customize the appearance of your thesis. You can change the entire document’s font or customize specific sections to stand out.

5.2.1 Changing the Overall Font

By default, LaTeX uses the Computer Modern font, but you can switch to other popular fonts using the fontspec package (for XeLaTeX or LuaLaTeX) or packages like mathptmx for traditional LaTeX.

To change the font to Times New Roman (commonly used in theses), you can add:

If you’re using XeLaTeX or LuaLaTeX, you can select any system font:

This will change the main font of the entire document to Times New Roman.

5.2.2 Customizing Specific Text

You can also change the font or style of specific parts of your thesis. For instance, to make a particular section bold or italicized:

5.2.3 Changing Font Sizes

If you want to customize the font size for specific parts of your thesis, LaTeX provides several options, ranging from \tiny to \Huge . You can use these to adjust the font size of headers, titles, or text:

5.3 Headers, Footers, and Page Numbers

Customizing the headers, footers, and page numbers is a common requirement for theses. LaTeX allows you to modify these elements using the fancyhdr package.

5.3.1 Using the fancyhdr Package

The fancyhdr package gives you full control over headers and footers, allowing you to insert text, section titles, and page numbers in various formats.

This example places the chapter title in the left side of the header and the page number in the right side of the footer. You can also add custom text or change the layout to suit your needs.

5.3.2 Page Numbering Options

Page numbers are usually required in theses, and LaTeX gives you several options for customizing them. You can control the position, style (e.g., Roman or Arabic numerals), and starting number.

To start with Roman numerals (typically for the front matter like the table of contents and abstract) and then switch to Arabic numerals for the main body:

You can also choose whether to place page numbers in the header or footer and whether they should be centered or aligned to the left or right.

5.4 Customizing Sections and Chapters

LaTeX automatically numbers sections, subsections, and chapters. However, you can customize how these numbers appear and modify the spacing or formatting around section titles.

5.4.1 Changing Section Numbering

If you want to change how sections and subsections are numbered (e.g., turning off section numbering), you can use the \section*{} and \chapter*{} commands to create unnumbered sections and chapters:

5.4.2 Customizing Chapter Titles

To customize the appearance of chapter titles, you can use the titlesec package:

This example formats the chapter title to be bold, large, and preceded by the word “Chapter.” The \chaptername and \thechapter commands ensure that both the word “Chapter” and its number appear.

5.4.3 Adjusting Spacing Around Titles

To modify the spacing before and after section or chapter titles, you can use the \titlespacing command:

This changes the space before and after chapter titles. The first value controls the indentation, the second controls the space before the title, and the third controls the space after.

5.5 Customizing Tables of Contents, Figures, and Tables

LaTeX automatically generates lists for the table of contents, figures, and tables. However, you may need to customize these lists for your thesis.

5.5.1 Customizing the Table of Contents

The tocloft package allows you to customize the table of contents (TOC) by adjusting the formatting and depth of sections included.

To modify the TOC depth (i.e., which levels are shown), use:

To format the appearance of the TOC:

5.5.2 Customizing the List of Figures and Tables

Similarly, you can adjust the formatting of the List of Figures or List of Tables by modifying their commands. Here’s an example of how to modify the appearance of figure captions:

This sets the figure labels to bold and the figure text to italics.

Chapter 6: Managing Citations and References

Managing references is one of the most important aspects of thesis writing. LaTeX simplifies this process with BibTeX.

Using BibTeX for Bibliography Create a .bib file for your references. Example:

In your LaTeX document, add the following commands:

Customizing Citation Styles You can change the citation style using different bibliography styles such as plain, ieeetr, or apa

Chapter 7: Creating Figures and Tables

Inserting figures and tables is crucial for academic writing. LaTeX provides a simple way to manage them.

Inserting Figures You can insert figures using the graphicx package:

Inserting Tables Tables are created using the tabular environment.

Chapter 8: Advanced Features for Thesis Writing

Cross-referencing Sections, Equations, and Figures You can cross-reference sections, figures, and equations using \label{} and \ref{}.

No responses yet

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Add me to your newsletter and keep me updated whenever you publish new blog posts

Enjoy this blog? Please encourage us by following on

10 min read

Share this post, published september 6, 2023 in general, how to use latex for thesis writing: a comprehensive guide, by scholarly, introduction.

Thesis writing is a crucial part of academic research, and presenting your work in a professional and polished manner is essential. LaTeX, a powerful typesetting system, can greatly enhance the quality and appearance of your thesis. In this comprehensive guide, we will explore how to use LaTeX for thesis writing, covering its history, benefits, best practices, common techniques, and more.

In the past, researchers and students relied on traditional word processors like Microsoft Word for thesis writing. However, these tools often lacked advanced typesetting features and resulted in inconsistent formatting. LaTeX emerged in the 1980s as a solution to these challenges, offering precise control over document layout, mathematical equations, and bibliographies.

Current State

Today, LaTeX remains a popular choice for academic writing, especially in fields such as mathematics, computer science, and physics. Its ability to handle complex equations, generate professional-looking documents, and facilitate collaboration makes it invaluable for thesis writing.

Future State

Looking ahead, LaTeX is expected to continue evolving with the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) techniques. AI-powered tools can enhance LaTeX's functionality by automating certain tasks, such as generating bibliographies or suggesting formatting improvements.

Superior Typesetting : LaTeX provides precise control over document layout, ensuring consistent and professional-looking theses.

Mathematical Equations : LaTeX excels at typesetting complex mathematical equations, making it ideal for scientific research.

Collaboration and Version Control : LaTeX's plain text format allows for easy collaboration and version control using platforms like GitHub.

Cross-Referencing and Citations : LaTeX's built-in features for cross-referencing and citations simplify the process of citing sources and creating bibliographies.

Templates and Customization : LaTeX offers a wide range of templates and allows for customization, enabling you to create a unique thesis.

Significance

The significance of using LaTeX for thesis writing cannot be overstated. It elevates the quality and professionalism of your work, making a positive impression on readers, reviewers, and potential employers. LaTeX's precise typesetting capabilities ensure that your thesis is visually appealing and easy to read, enhancing its overall impact.

Best Practices

To make the most of LaTeX for thesis writing, consider the following best practices:

Learn the Basics : Familiarize yourself with LaTeX's syntax and commands by referring to online tutorials and guides.

Organize Your Project : Divide your thesis into separate files for each chapter or section to improve organization and facilitate collaboration.

Use Version Control : Utilize version control systems like Git to track changes and collaborate with others effectively.

Leverage Templates : Start with a pre-designed LaTeX template that matches your field or university's requirements to save time and ensure consistency.

Proofread and Test : Regularly proofread your document and compile it to ensure proper formatting, especially after making significant changes.

Pros and Cons

Professional Appearance : LaTeX produces documents with a polished and professional appearance.

Mathematical Typesetting : LaTeX excels at typesetting complex mathematical equations.

Cross-Referencing : LaTeX's built-in cross-referencing feature simplifies referencing and citation.

Collaboration : LaTeX's plain text format allows for easy collaboration and version control.

Customization : LaTeX offers extensive customization options, allowing you to create a unique thesis.

Learning Curve : LaTeX has a steeper learning curve compared to traditional word processors.

Limited WYSIWYG Editing : LaTeX's focus on typesetting means that the visual editing experience may be less intuitive.

Compatibility Issues : Some journals or institutions may require submissions in formats other than LaTeX.

Complex Tables and Graphics : Creating complex tables and graphics in LaTeX can be challenging for beginners.

Time-Consuming : Mastering LaTeX and troubleshooting issues may require a significant time investment.

When considering LaTeX for thesis writing, it's important to compare it with other tools available. Here are a few popular alternatives:

Microsoft Word : While Word is widely used, it may struggle with complex mathematical equations and lacks the precise typesetting control of LaTeX.

Google Docs : Google Docs offers collaborative features, but its typesetting capabilities are limited compared to LaTeX.

Overleaf : Overleaf is an online LaTeX editor that simplifies collaboration but requires an internet connection.

Common Techniques

Document Structure : Organize your thesis into chapters, sections, and subsections using LaTeX's hierarchical structure.

Mathematical Equations : Utilize LaTeX's math mode and mathematical environments to typeset equations with clarity.

Citations and Bibliographies : Use LaTeX's built-in citation commands and BibTeX or BibLaTeX for managing references.

Tables and Figures : Create professional-looking tables and figures using LaTeX's table and figure environments.

Cross-Referencing : Take advantage of LaTeX's labels and cross-referencing commands to refer to equations, figures, and sections.

While LaTeX offers numerous benefits, it also presents some challenges:

Learning Curve : LaTeX has a steeper learning curve compared to traditional word processors, requiring time and effort to master.

Debugging and Troubleshooting : Troubleshooting LaTeX errors can be challenging, especially for beginners.

Compatibility Issues : Some journals or institutions may require submissions in formats other than LaTeX, necessitating conversion.

Complex Tables and Graphics : Creating complex tables and graphics in LaTeX can be time-consuming and require advanced knowledge.

Potential Online Apps

If you're interested in exploring LaTeX for thesis writing, consider the following online apps:

Overleaf - An online LaTeX editor that simplifies collaboration and provides templates and tutorials.

ShareLaTeX - A cloud-based LaTeX editor with real-time collaboration features and extensive libraries.

Scholarly - An AI-powered platform for academic writing that offers LaTeX integration and advanced text completion.

Authorea - An online collaborative writing platform that supports LaTeX and provides version control.

Papeeria - A web-based LaTeX editor with features like real-time collaboration and project management.

LaTeX is a powerful tool for thesis writing, offering superior typesetting, mathematical equation support, collaboration capabilities, and customization options. By following best practices and leveraging its features, you can create a professional and visually appealing thesis. While LaTeX has a learning curve and some challenges, its benefits make it an invaluable asset for researchers and students. Consider exploring online apps like Overleaf, ShareLaTeX, Scholarly, Authorea, and Papeeria to enhance your LaTeX experience and streamline your thesis writing process.

Keep Reading

Create Flashcards for Free: The Ultimate Study Hack

Posted November 27, 2024

Free Study Card Maker: Easy Learning Solutions

Effortless Study Cards with Free Flashcard Generator

Unlock Learning with Free Flashcard Maker

Try scholarly.

It's completely free, simple to use, and easy to get started.

Join thousands of students and educators today.

Are you a school or organization? Contact us

© 2024 Scholarly. All rights reserved.

Overleaf for Scholarly Writing & Publication: LaTeX Theses and Dissertations

- Reference Managers and Overleaf

- Adding Graphs, Tables, and Images

- Using Templates on Overleaf

- LaTeX Theses and Dissertations

LaTeX Theses and Dissertatons

Tips and tools for writing your LaTeX thesis or dissertation in Overleaf, including templates, managing references , and getting started guides.

Managing References

BibTeX is a file format used for lists of references for LaTeX documents. Many citation management tools support the ability to export and import lists of references in .bib format. Some reference management tools can generate BibTeX files of your library or folders for use in your LaTeX documents.

LaTeX on Wikibooks has a Bibliography Management page.

Find list of BibTeX styles available on Overleaf here

View a video tutorial on how to include a bibliography using BibTeX here

Collaborate with Overleaf

Collaboration tools

Every project you create has a secret link. Just send it to your co-authors, and they can review, comment and edit. Overleaf synchronizes changes from all authors, so everyone always has the latest version. More advanced tools include protected projects and integration with Git.

Collaborate online and offline with Overleaf and Git

Protected projects with Overleaf Pro

Getting Started with Your Thesis or Dissertation

How to get started writing your thesis in LaTeX

Writing a thesis or dissertation in LaTeX can be challenging, but the end result is well worth it - nothing looks as good as a LaTeX-produced pdf, and for large documents it's a lot easier than fighting with formatting and cross-referencing in MS Word. Review this video from Overleaf to help you get started writing your thesis in LaTeX, using a standard thesis template from the Overleaf Gallery .

You can upload your own thesis template to the Overleaf Gallery if your university provides a set of LaTeX template files or you may find your university's thesis template already in the Overleaf Gallery.

This video assumes you've used LaTeX before and are familiar with the standard commands (see our other tutorial videos if not), and focuses on how to work with a large project split over multiple files.

How to Write your Thesis/Dissertation in LaTeX: A Five-Part Guide

Five-Part LaTeX Thesis/Dissertation Writing Guide

Part 1: Basic Structure corresponding video

Part 2: Page Layout corresponding video

Part 3: Figures, Subfigures and Tables corresponding video

Part 4: Bibliographies with Biblatex corresponding video

Part 5: Customizing Your Title Page and Abstract corresponding video

Link Your ORCID

Link yo ur ORCiD account to your Overleaf account via the ORCID @ CMU Portal

Open Knowledge Librarian

- << Previous: Using Templates on Overleaf

- Last Updated: Oct 4, 2023 9:31 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.cmu.edu/overleaf

because LaTeX matters

Writing a thesis in latex.

Writing a thesis is a time-intensive endeavor. Fortunately, using LaTeX, you can focus on the content rather than the formatting of your thesis. The following article summarizes the most important aspects of writing a thesis in LaTeX, providing you with a document skeleton (at the end) and lots of additional tips and tricks.

Document class

The first choice in most cases will be the report document class:

See here for a complete list of options. Personally, I use draft a lot. It replaces figures with a box of the size of the figure. It saves you time generating the document. Furthermore, it will highlight justification and hyphenation errors ( Overfull \hbox ).

Check with your college or university. They may have an official or unofficial template/class-file to be used for writing a thesis.

Again, follow the instructions of your institution if there are any. Otherwise, LaTeX provides a few basic command for the creation of a title page.

Use \today as \date argument to automatically generate the current date. Leave it empty in case you don’t want the date to be printed. As shown in the example, the author command can be extended to print several lines.

For a more sophisticated title page, the titlespages package has a nice collection of pre-formatted front pages. For different affiliations use the authblk package, see here for some examples.

Contents (toc/lof/lot)

Nothing special here.

The tocloft package offers great flexibility in formatting contents. See here for a selection of possibilities.

Often, the page numbers are changed to roman for this introductory part of the document and only later, for the actual content, arabic page numbering is used. This can be done by placing the following commands before and after the contents commands respectively.

LaTeX provides the abstract environment which will print “Abstract” centered as a title.

The actual content

The most important and extensive part is the content. I strongly suggest to split up every chapter into an individual file and load them in the main tex-file.

In thesis.tex:

In chapter1.tex:

This way, you can typeset single chapters or parts of the whole thesis only, by commenting out what you want to exclude. Remember, the document can only be generated from the main file (thesis.tex), since the individual chapters are missing a proper LaTeX document structure.

See here for a discussion on whether to use \input or \include .

Bibliography

The most convenient way is to use a bib-tex file that contains all your references. You can download bibtex items for articles, books, etc. from Google scholar or often directly from the journal websites.

Two packages are commonly used to personalize bibliographies, the newer biblatex and the natbib package, which has been around for many years. These packages offer great flexibility in customizing the look of a bibliography, depending on the preference in the field or the author.

Other commonly used packages

- graphicx : Indispensable when working with figures/graphs.

- subfig : Controlling arrangement of several figures (e.g. 2×2 matrix)

- minitoc : Adds mini table of contents to every chapter

- nomencl : Generate and format a nomenclature

- listings : Source code printer for LaTeX

- babel : Multilingual package for standard document classes

- fancyhdr : Controlling header and footer

- hyperref : Hypertext links for LaTeX

- And many more

Minimal example code

I’m aware that this short post on writing a thesis only covers the very basics of a vast topic. However, it will help you getting started and focussing on the content of your thesis rather than the formatting of the document.

Share this:

16 comments.

8. June 2012 at 7:09

I would rather recommend a documentclass like memoir or scrreprt (from KOMA-Script), since they are much more flexible than report.

8. June 2012 at 8:12

I agree, my experience with them is limited though. Thanks for the addendum. Here is the documentation: memoir , scrreprt (KOMA script)

8. June 2012 at 8:02

Nice post Tom. I’m actually writing a two-part (or three) on Writing the PhD thesis: the tools . Feel free to comment, I hope to update it as I write my thesis, so any suggestions are welcome.

8. June 2012 at 8:05

Thanks for the link. I just saw your post and thought I should really check out git sometimes :-). Best, Tom.

8. June 2012 at 8:10

Yes, git is awesome. It can be a bit overwhelming with all the options and commands, but if you’re just working alone, and probably on several machines, then you can do everything effortlessly with few commands.

11. June 2012 at 2:15

That’s what has kept me so far. But I’ll definitely give it a try. Thanks!

8. June 2012 at 8:08

What a great overview. Thank you, this will come handy… when I finally get myself to start writing that thesis 🙂

8. June 2012 at 14:12

Thanks and good luck with your thesis! Tom.

9. June 2012 at 4:08

Hi, I can recommend two important packages: lineno.sty to insert linenumbers (really helpful in the debugging phase) and todonotes (allows you to insert todo-notes for things you still have to do.)

11. June 2012 at 0:48

Thanks Uwe! I wrote an article on both, lineno and todonotes . Here is the documentation: lineno and todonotes for more details.

12. June 2012 at 15:51

Thanks for the post, i’m currently writing my master thesis 🙂

A small note: it seems that subfig is deprecated for the subcaption package: https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/LaTeX/Floats,_Figures_and_Captions#Subfloats