- SpringerLink shop

Types of journal articles

It is helpful to familiarise yourself with the different types of articles published by journals. Although it may appear there are a large number of types of articles published due to the wide variety of names they are published under, most articles published are one of the following types; Original Research, Review Articles, Short reports or Letters, Case Studies, Methodologies.

Original Research:

This is the most common type of journal manuscript used to publish full reports of data from research. It may be called an Original Article, Research Article, Research, or just Article, depending on the journal. The Original Research format is suitable for many different fields and different types of studies. It includes full Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion sections.

Short reports or Letters:

These papers communicate brief reports of data from original research that editors believe will be interesting to many researchers, and that will likely stimulate further research in the field. As they are relatively short the format is useful for scientists with results that are time sensitive (for example, those in highly competitive or quickly-changing disciplines). This format often has strict length limits, so some experimental details may not be published until the authors write a full Original Research manuscript. These papers are also sometimes called Brief communications .

Review Articles:

Review Articles provide a comprehensive summary of research on a certain topic, and a perspective on the state of the field and where it is heading. They are often written by leaders in a particular discipline after invitation from the editors of a journal. Reviews are often widely read (for example, by researchers looking for a full introduction to a field) and highly cited. Reviews commonly cite approximately 100 primary research articles.

TIP: If you would like to write a Review but have not been invited by a journal, be sure to check the journal website as some journals to not consider unsolicited Reviews. If the website does not mention whether Reviews are commissioned it is wise to send a pre-submission enquiry letter to the journal editor to propose your Review manuscript before you spend time writing it.

Case Studies:

These articles report specific instances of interesting phenomena. A goal of Case Studies is to make other researchers aware of the possibility that a specific phenomenon might occur. This type of study is often used in medicine to report the occurrence of previously unknown or emerging pathologies.

Methodologies or Methods

These articles present a new experimental method, test or procedure. The method described may either be completely new, or may offer a better version of an existing method. The article should describe a demonstrable advance on what is currently available.

Back │ Next

- Insights blog

Different types of research articles

A guide for early career researchers.

In scholarly literature, there are many different kinds of articles published every year. Original research articles are often the first thing you think of when you hear the words ‘journal article’. In reality, research work often results in a whole mixture of different outputs and it’s not just the final research article that can be published.

Finding a home to publish supporting work in different formats can help you start publishing sooner, allowing you to build your publication record and research profile.

But before you do, it’s very important that you check the instructions for authors and the aims and scope of the journal(s) you’d like to submit to. These will tell you whether they accept the type of article you’re thinking of writing and what requirements they have around it.

Understanding the different kind of articles

There’s a huge variety of different types of articles – some unique to individual journals – so it’s important to explore your options carefully. While it would be impossible to cover every single article type here, below you’ll find a guide to the most common research articles and outputs you could consider submitting for publication.

Book review

Many academic journals publish book reviews, which aim to provide insight and opinion on recently published scholarly books. Writing book reviews is often a good way to begin academic writing. It can help you get your name known in your field and give you valuable experience of publishing before you write a full-length article.

If you’re keen to write a book review, a good place to start is looking for journals that publish or advertise the books they have available for review. Then it’s just a matter of putting yourself forward for one of them.

You can check whether a journal publishes book reviews by browsing previous issues or by seeing if a book review editor is listed on the editorial board. In addition, some journals publish other types of reviews, such as film, product, or exhibition reviews, so it’s worth bearing those in mind as options as well.

Get familiar with instructions for authors

Be prepared, speed up your submission, and make sure nothing is forgotten by understanding a journal’s individual requirements.

Publishing tips, direct to your inbox

Expert tips and guidance on getting published and maximizing the impact of your research. Register now for weekly insights direct to your inbox.

Case report

A medical case report – also sometimes called a clinical case study – is an original short report that provides details of a single patient case.

Case reports include detailed information on the symptoms, signs, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of an individual patient. They remain one of the cornerstones of medical progress and provide many new ideas in medicine.

Depending on the journal, a case report doesn’t necessarily need to describe an especially novel or unusual case as there is benefit from collecting details of many standard cases.

Take a look at F1000Research’s guidance on case reports , to understand more about what’s required in them. And don’t forget that for all studies involving human participants, informed written consent to take part in the research must be obtained from the participants – find out more about consent to publish.

Clinical study

In medicine, a clinical study report is a type of article that provides in-depth detail on the methods and results of a clinical trial. They’re typically similar in length and format to original research articles.

Most journals now require that you register protocols for clinical trials you’re involved with in a publicly accessible registry. A list of eligible registries can be found on the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) . Trials can also be registered at clinicaltrials.gov or the EU Clinical Trials Register . Once registered, your trial will be assigned a clinical trial number (CTN).

Before you submit a clinical study, you’ll need to include clinical trial numbers and registration dates in the manuscript, usually in the abstract and methods sections.

Commentaries and letters to editors

Letters to editors, as well as ‘replies’ and ‘discussions’, are usually brief comments on topical issues of public and political interest (related to the research field of the journal), anecdotal material, or readers’ reactions to material published in the journal.

Commentaries are similar, though they may be slightly more in-depth, responding to articles recently published in the journal. There may be a ‘target article’ which various commentators are invited to respond to.

You’ll need to look through previous issues of any journal you’re interested in writing for and review the instructions for authors to see which types of these articles (if any) they accept.

Conference materials

Many of our medical journals accept conference material supplements. These are open access peer-reviewed, permanent, and citable publications within the journal. Conference material supplements record research around a common thread, as presented at a workshop, congress, or conference, for the scientific record. They can include the following types of articles:

Poster extracts

Conference abstracts

Presentation extracts

Find out more about submitting conference materials.

Data notes are a short peer-reviewed article type that concisely describe research data stored in a repository. Publishing a data note can help you to maximize the impact of your data and gain appropriate credit for your research.

Data notes promote the potential reuse of research data and include details of why and how the data were created. They do not include any analysis but they can be linked to a research article incorporating analysis of the published dataset, as well as the results and conclusions.

F1000Research enables you to publish your data note rapidly and openly via an author-centric platform. There is also a growing range of options for publishing data notes in Taylor & Francis journals, including in All Life and Big Earth Data .

Read our guide to data notes to find out more.

Letters or short reports

Letters or short reports (sometimes known as brief communications or rapid communications) are brief reports of data from original research.

Editors publish these reports where they believe the data will be interesting to many researchers and could stimulate further research in the field. There are even entire journals dedicated to publishing letters.

As they’re relatively short, the format is useful for researchers with results that are time sensitive (for example, those in highly competitive or quickly-changing disciplines). This format often has strict length limits, so some experimental details may not be published until the authors write a full original research article.

Brief reports (previously called Research Notes) are a type of short report published by F1000Research – part of the Taylor & Francis Group. To find out more about the requirements for a brief report, take a look at F1000Research’s guidance .

Method article

A method article is a medium length peer-reviewed, research-focused article type that aims to answer a specific question. It also describes an advancement or development of current methodological approaches and research procedures (akin to a research article), following the standard layout for research articles. This includes new study methods, substantive modifications to existing methods, or innovative applications of existing methods to new models or scientific questions. These should include adequate and appropriate validation to be considered, and any datasets associated with the paper must publish all experimental controls and make full datasets available.

Posters and slides

With F1000Research, you can publish scholarly posters and slides covering basic scientific, translational, and clinical research within the life sciences and medicine. You can find out more about how to publish posters and slides on the F1000Research website .

Registered report

A Registered Report consists of two different kinds of articles: a study protocol and an original research article.

This is because the review process for Registered Reports is divided into two stages. In Stage 1, reviewers assess study protocols before data is collected. In Stage 2, reviewers consider the full published study as an original research article, including results and interpretation.

Taking this approach, you can get an in-principle acceptance of your research article before you start collecting data. We’ve got further guidance on Registered Reports here , and you can also read F1000Research’s guidance on preparing a Registered Report .

Research article

Original research articles are the most common type of journal article. They’re detailed studies reporting new work and are classified as primary literature.

You may find them referred to as original articles, research articles, research, or even just articles, depending on the journal.

Typically, especially in STEM subjects, these articles will include Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion sections. However, you should always check the instructions for authors of your chosen journal to see whether it specifies how your article should be structured. If you’re planning to write an original research article, take a look at our guidance on writing a journal article .

Review article

Review articles provide critical and constructive analysis of existing published literature in a field. They’re usually structured to provide a summary of existing literature, analysis, and comparison. Often, they identify specific gaps or problems and provide recommendations for future research.

Unlike original research articles, review articles are considered as secondary literature. This means that they generally don’t present new data from the author’s experimental work, but instead provide analysis or interpretation of a body of primary research on a specific topic. Secondary literature is an important part of the academic ecosystem because it can help explain new or different positions and ideas about primary research, identify gaps in research around a topic, or spot important trends that one individual research article may not.

There are 3 main types of review article

Literature review

Presents the current knowledge including substantive findings as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to a particular topic.

Systematic review

Identifies, appraises and synthesizes all the empirical evidence that meets pre-specified eligibility criteria to answer a specific research question. Researchers conducting systematic reviews use explicit, systematic methods that are selected with a view aimed at minimizing bias, to produce more reliable findings to inform decision making.

Meta-analysis

A quantitative, formal, epidemiological study design used to systematically assess the results of previous research to derive conclusions about that body of research. Typically, but not necessarily, a meta-analysis study is based on randomized, controlled clinical trials.

Take a look at our guide to writing a review article for more guidance on what’s required.

Software tool articles

A software tool article – published by F1000Research – describes the rationale for the development of a new software tool and details of the code used for its construction.

The article should provide examples of suitable input data sets and include an example of the output that can be expected from the tool and how this output should be interpreted. Software tool articles submitted to F1000Research should be written in open access programming languages. Take a look at their guidance for more details on what’s required of a software tool article.

Further resources

Ready to write your article, but not sure where to start?

For more guidance on how to prepare and write an article for a journal you can download the Writing your paper eBook .

- UNO Criss Library

Social Work Research Guide

What is a research journal.

- Find Articles

- Find E-Books and Books

Reading an Academic Article

- Free Online Resources

- Reference and Writing

- Citation Help This link opens in a new window

Anatomy of a Scholarly Article

TIP: When possible, keep your research question(s) in mind when reading scholarly articles. It will help you to focus your reading.

Title : Generally are straightforward and describe what the article is about. Titles often include relevant key words.

Abstract : A summary of the author(s)'s research findings and tells what to expect when you read the full article. It is often a good idea to read the abstract first, in order to determine if you should even bother reading the whole article.

Discussion and Conclusion : Read these after the Abstract (even though they come at the end of the article). These sections can help you see if this article will meet your research needs. If you don’t think that it will, set it aside.

Introduction : Describes the topic or problem researched. The authors will present the thesis of their argument or the goal of their research.

Literature Review : May be included in the introduction or as its own separate section. Here you see where the author(s) enter the conversation on this topic. That is to say, what related research has come before, and how do they hope to advance the discussion with their current research?

Methods : This section explains how the study worked. In this section, you often learn who and how many participated in the study and what they were asked to do. You will need to think critically about the methods and whether or not they make sense given the research question.

Results : Here you will often find numbers and tables. If you aren't an expert at statistics this section may be difficult to grasp. However you should attempt to understand if the results seem reasonable given the methods.

Works Cited (also be called References or Bibliography ): This section comprises the author(s)’s sources. Always be sure to scroll through them. Good research usually cites many different kinds of sources (books, journal articles, etc.). As you read the Works Cited page, be sure to look for sources that look like they will help you to answer your own research question.

Adapted from http://library.hunter.cuny.edu/research-toolkit/how-do-i-read-stuff/anatomy-of-a-scholarly-article

A research journal is a periodical that contains articles written by experts in a particular field of study who report the results of research in that field. The articles are intended to be read by other experts or students of the field, and they are typically much more sophisticated and advanced than the articles found in general magazines. This guide offers some tips to help distinguish scholarly journals from other periodicals.

CHARACTERISTICS OF RESEARCH JOURNALS

PURPOSE : Research journals communicate the results of research in the field of study covered by the journal. Research articles reflect a systematic and thorough study of a single topic, often involving experiments or surveys. Research journals may also publish review articles and book reviews that summarize the current state of knowledge on a topic.

APPEARANCE : Research journals lack the slick advertising, classified ads, coupons, etc., found in popular magazines. Articles are often printed one column to a page, as in books, and there are often graphs, tables, or charts referring to specific points in the articles.

AUTHORITY : Research articles are written by the person(s) who did the research being reported. When more than two authors are listed for a single article, the first author listed is often the primary researcher who coordinated or supervised the work done by the other authors. The most highly‑regarded scholarly journals are typically those sponsored by professional associations, such as the American Psychological Association or the American Chemical Society.

VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY : Articles submitted to research journals are evaluated by an editorial board and other experts before they are accepted for publication. This evaluation, called peer review, is designed to ensure that the articles published are based on solid research that meets the normal standards of the field of study covered by the journal. Professors sometimes use the term "refereed" to describe peer-reviewed journals.

WRITING STYLE : Articles in research journals usually contain an advanced vocabulary, since the authors use the technical language or jargon of their field of study. The authors assume that the reader already possesses a basic understanding of the field of study.

REFERENCES : The authors of research articles always indicate the sources of their information. These references are usually listed at the end of an article, but they may appear in the form of footnotes, endnotes, or a bibliography.

PERIODICALS THAT ARE NOT RESEARCH JOURNALS

POPULAR MAGAZINES : These are periodicals that one typically finds at grocery stores, airport newsstands, or bookstores at a shopping mall. Popular magazines are designed to appeal to a broad audience, and they usually contain relatively brief articles written in a readable, non‑technical language.

Examples include: Car and Driver , Cosmopolitan , Esquire , Essence , Gourmet , Life , People Weekly , Readers' Digest , Rolling Stone , Sports Illustrated , Vanity Fair , and Vogue .

NEWS MAGAZINES : These periodicals, which are usually issued weekly, provide information on topics of current interest, but their articles seldom have the depth or authority of scholarly articles.

Examples include: Newsweek , Time , U.S. News and World Report .

OPINION MAGAZINES : These periodicals contain articles aimed at an educated audience interested in keeping up with current events or ideas, especially those pertaining to topical issues. Very often their articles are written from a particular political, economic, or social point of view.

Examples include: Catholic World , Christianity Today , Commentary , Ms. , The Militant , Mother Jones , The Nation , National Review , The New Republic , The Progressive , and World Marxist Review .

TRADE MAGAZINES : People who need to keep up with developments in a particular industry or occupation read these magazines. Many trade magazines publish one or more special issues each year that focus on industry statistics, directory lists, or new product announcements.

Examples include: Beverage World , Progressive Grocer , Quick Frozen Foods International , Rubber World , Sales and Marketing Management , Skiing Trade News , and Stores .

Literature Reviews

- Literature Review Guide General information on how to organize and write a literature review.

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It Contains two sets of questions to help students review articles, and to review their own literature reviews.

- << Previous: Find E-Books and Books

- Next: Statistics >>

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 10:14 AM

- URL: https://libguides.unomaha.edu/social_work

- Richard G. Trefry Library

Q. What's the difference between a research article (or research study) and a review article?

- Course-Specific

- Textbooks & Course Materials

- Tutoring & Classroom Help

- Writing & Citing

- 44 Articles & Journals

- 5 Artificial Intelligence

- 11 Capstone/Thesis/Dissertation Research

- 37 Databases

- 56 Information Literacy

- 9 Interlibrary Loan

- 9 Need help getting started?

- 22 Technical Help

Answered By: Priscilla Coulter Last Updated: Jul 26, 2024 Views: 233602

A research paper is a primary source ...that is, it reports the methods and results of an original study performed by the authors . The kind of study may vary (it could have been an experiment, survey, interview, etc.), but in all cases, raw data have been collected and analyzed by the authors , and conclusions drawn from the results of that analysis.

Research papers follow a particular format. Look for:

- A brief introduction will often include a review of the existing literature on the topic studied, and explain the rationale of the author's study. This is important because it demonstrates that the authors are aware of existing studies, and are planning to contribute to this existing body of research in a meaningful way (that is, they're not just doing what others have already done).

- A methods section, where authors describe how they collected and analyzed data. Statistical analyses are included. This section is quite detailed, as it's important that other researchers be able to verify and/or replicate these methods.

- A results section describes the outcomes of the data analysis. Charts and graphs illustrating the results are typically included.

- In the discussion , authors will explain their interpretation of their results and theorize on their importance to existing and future research.

- References or works cited are always included. These are the articles and books that the authors drew upon to plan their study and to support their discussion.

You can use the library's databases to search for research articles:

- A research article will nearly always be published in a peer-reviewed journal; click here for instructions on limiting your searches to peer-reviewed articles .

- If you have a particular type of study in mind, you can include keywords to describe it in your search . For instance, if you would like to see studies that used surveys to collect data, you can add "survey" to your topic in the database's search box. See this example search in our EBSCO databases: " bullying and survey ".

- Several of our databases have special limiting options that allow you to select specific methodologies. See, for instance, the " Methodology " box in ProQuest's PsycARTICLES Advanced Search (scroll down a bit to see it). It includes options like "Empirical Study" and "Qualitative Study", among many others.

A review article is a secondary source ...it is written about other articles, and does not report original research of its own. Review articles are very important, as they draw upon the articles that they review to suggest new research directions, to strengthen support for existing theories and/or identify patterns among exising research studies. For student researchers, review articles provide a great overview of the existing literature on a topic. If you find a literature review that fits your topic, take a look at its references/works cited list for leads on other relevant articles and books!

You can use the library's article databases to find literature reviews as well! Click here for tips.

- Share on Facebook

Was this helpful? Yes 7 No 1

Related Topics

- Articles & Journals

- Information Literacy

Need personalized help? Librarians are available 365 days/nights per year! See our schedule.

Learn more about how librarians can help you succeed.

Understanding Scientific Journals and Articles: How to approach reading journal articles

by Anthony Carpi, Ph.D., Anne E. Egger, Ph.D., Natalie H. Kuldell

Listen to this reading

Did you know that scientific literature goes all the way back to 600 BCE? Although scientific articles have changed some – for example, Isaac Newton wrote about the fun he had with prisms in a 1672 scientific article – the basics remain the same. This ensures that published research becomes part of the archive of scientific knowledge upon which other scientists can build.

Scientists make their research available to the community by publishing it in scientific journals.

In scientific papers, scientists explain the research that they are building on, their research methods, data and data analysis techniques, and their interpretation of the data.

Understanding how to read scientific papers is a critical skill for scientists and students of science.

We've all read the headlines at the supermarket checkout line: "Aliens Abduct New Jersey School Teacher" or "Quadruplets Born to 99-Year-Old Woman: Exclusive Photos Inside." Journals like the National Enquirer sell copies by publishing sensational headlines, and most readers believe only a fraction of what is printed. A person more interested in news than gossip could buy a publication like Time, Newsweek or Discover . These magazines publish information on current news and events, including recent scientific advances. These are not original reports of scientific research , however. In fact, most of these stories include phrases like, "A group of scientists recently published their findings on..." So where do scientists publish their findings?

Scientists publish their original research in scientific journals, which are fundamentally different from news magazines. The articles in scientific journals are not written by journalists – they are written by scientists. Scientific articles are not sensational stories intended to entertain the reader with an amazing discovery, nor are they news stories intended to summarize recent scientific events, nor even records of every successful and unsuccessful research venture. Instead, scientists write articles to describe their findings to the community in a transparent manner.

- Scientific journals vs. popular media

Within a scientific article, scientists present their research questions, the methods by which the question was approached, and the results they achieved using those methods. In addition, they present their analysis of the data and describe some of the interpretations and implications of their work. Because these articles report new work for the first time, they are called primary literature . In contrast, articles or news stories that review or report on scientific research already published elsewhere are referred to as secondary .

The articles in scientific journals are different from news articles in another way – they must undergo a process called peer review , in which other scientists (the professional peers of the authors) evaluate the quality and merit of research before recommending whether or not it should be published (see our Peer Review module). This is a much lengthier and more rigorous process than the editing and fact-checking that goes on at news organizations. The reason for this thorough evaluation by peers is that a scientific article is more than a snapshot of what is going on at a certain time in a scientist's research. Instead, it is a part of what is collectively called the scientific literature, a global archive of scientific knowledge. When published, each article expands the library of scientific literature available to all scientists and contributes to the overall knowledge base of the discipline of science.

Comprehension Checkpoint

- Scientific journals: Degrees of specialization

Figure 1: Nature : An example of a scientific journal.

There are thousands of scientific journals that publish research articles. These journals are diverse and can be distinguished according to their field of specialization. Among the most broadly targeted and competitive are journals like Cell , the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), Nature , and Science that all publish a wide variety of research articles (see Figure 1 for an example). Cell focuses on all areas of biology, NEJM on medicine, and both Science and Nature publish articles in all areas of science. Scientists submit manuscripts for publication in these journals when they feel their work deserves the broadest possible audience.

Just below these journals in terms of their reach are the top-tier disciplinary journals like Analytical Chemistry, Applied Geochemistry, Neuron, Journal of Geophysical Research , and many others. These journals tend to publish broad-based research focused on specific disciplines, such as chemistry, geology, neurology, nuclear physics, etc.

Next in line are highly specialized journals, such as the American Journal of Potato Research, Grass and Forage Science, the Journal of Shellfish Research, Neuropeptides, Paleolimnology , and many more. While the research published in various journals does not differ in terms of the quality or the rigor of the science described, it does differ in its degree of specialization: These journals tend to be more specialized, and thus appeal to a more limited audience.

All of these journals play a critical role in the advancement of science and dissemination of information (see our Utilizing the Scientific Literature module for more information). However, to understand how science is disseminated through these journals, you must first understand how the articles themselves are formatted and what information they contain. While some details about format vary between journals and even between articles in the same journal, there are broad characteristics that all scientific journal articles share.

- The standard format of journal articles

In June of 2005, the journal Science published a research report on a sighting of the ivory-billed woodpecker, a bird long considered extinct in North America (Fitzpatrick et al., 2005). The work was of such significance and broad interest that it was displayed prominently on the cover (Figure 2) and highlighted by an editorial at the front of the journal (Kennedy, 2005). The authors were aware that their findings were likely to be controversial, and they worked especially hard to make their writing clear. Although the article has no headings within the text, it can easily be divided into sections:

Figure 2: A picture of the cover of Science from June 3, 2005.

Title and authors: The title of a scientific article should concisely and accurately summarize the research . Here, the title used is "Ivory-billed Woodpecker ( Campephilus principalis ) Persists in North America." While it is meant to capture attention, journals avoid using misleading or overly sensational titles (you can imagine that a tabloid might use the headline "Long-dead Giant Bird Attacks Canoeists!"). The names of all scientific contributors are listed as authors immediately after the title. You may be used to seeing one or maybe two authors for a book or newspaper article, but this article has seventeen authors! It's unlikely that all seventeen of those authors sat down in a room and wrote the manuscript together. Instead, the authorship reflects the distribution of the workload and responsibility for the research, in addition to the writing. By convention, the scientist who performed most of the work described in the article is listed first, and it is likely that the first author did most of the writing. Other authors had different contributions; for example, Gene Sparling is the person who originally spotted the bird in Arkansas and was subsequently contacted by the scientists at the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. In some cases, but not in the woodpecker article, the last author listed is the senior researcher on the project, or the scientist from whose lab the project originated. Increasingly, journals are requesting that authors detail their exact contributions to the research and writing associated with a particular study.

Abstract: The abstract is the first part of the article that appears right after the listing of authors in an article. In it, the authors briefly describe the research question, the general methods , and the major findings and implications of the work. Providing a summary like this at the beginning of an article serves two purposes: First, it gives readers a way to decide whether the article in question discusses research that interests them, and second, it is entered into literature databases as a means of providing more information to people doing scientific literature searches. For both purposes, it is important to have a short version of the full story. In this case, all of the critical information about the timing of the study, the type of data collected, and the potential interpretations of the findings is captured in four straightforward sentences as seen below:

The ivory-billed woodpecker ( Campephilus principalis ), long suspected to be extinct, has been rediscovered in the Big Woods region of eastern Arkansas. Visual encounters during 2004 and 2005, and analysis of a video clip from April 2004, confirm the existence of at least one male. Acoustic signatures consistent with Campephilus display drums also have been heard from the region. Extensive efforts to find birds away from the primary encounter site remain unsuccessful, but potential habitat for a thinly distributed source population is vast (over 220,000 hectares).

Introduction: The central research question and important background information are presented in the introduction. Because science is a process that builds on previous findings, relevant and established scientific knowledge is cited in this section and then listed in the References section at the end of the article. In many articles, a heading is used to set this and subsequent sections apart, but in the woodpecker article the introduction consists of the first three paragraphs, in which the history of the decline of the woodpecker and previous studies are cited. The introduction is intended to lead the reader to understand the authors' hypothesis and means of testing it. In addition, the introduction provides an opportunity for the authors to show that they are aware of the work that scientists have done before them and how their results fit in, explicitly building on existing knowledge.

Materials and methods: In this section, the authors describe the research methods they used (see The Practice of Science module for more information on these methods). All procedures, equipment, measurement parameters , etc. are described in detail sufficient for another researcher to evaluate and/or reproduce the research. In addition, authors explain the sources of error and procedures employed to reduce and measure the uncertainty in their data (see our Uncertainty, Error, and Confidence module). The detail given here allows other scientists to evaluate the quality of the data collected. This section varies dramatically depending on the type of research done. In an experimental study, the experimental set-up and procedure would be described in detail, including the variables , controls , and treatment . The woodpecker study used a descriptive research approach, and the materials and methods section is quite short, including the means by which the bird was initially spotted (on a kayaking trip) and later photographed and videotaped.

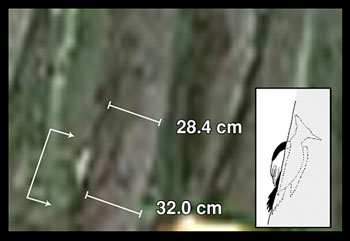

Results: The data collected during the research are presented in this section, both in written form and using tables, graphs, and figures (see our Using Graphs and Visual Data module). In addition, all statistical and data analysis techniques used are presented (see our Statistics in Science module). Importantly, the data should be presented separately from any interpretation by the authors. This separation of data from interpretation serves two purposes: First, it gives other scientists the opportunity to evaluate the quality of the actual data, and second, it allows others to develop their own interpretations of the findings based on their background knowledge and experience. In the woodpecker article, the data consist largely of photographs and videos (see Figure 3 for an example). The authors include both the raw data (the photograph) and their analysis (the measurement of the tree trunk and inferred length of the bird perched on the trunk). The sketch of the bird on the right-hand side of the photograph is also a form of analysis, in which the authors have simplified the photograph to highlight the features of interest. Keeping the raw data (in the form of a photograph) facilitated reanalysis by other scientists: In early 2006, a team of researchers led by the American ornithologist David Sibley reanalyzed the photograph in Figure 3 and came to the conclusion that the bird was not an ivory-billed woodpecker after all (Sibley et al, 2006).

Figure 3: An example of the data presented in the Ivory-billed woodpecker article (Fitzpatrick et al ., 2005, Figure 1).

Discussion and conclusions: In this section, authors present their interpretation of the data , often including a model or idea they feel best explains their results. They also present the strengths and significance of their work. Naturally, this is the most subjective section of a scientific research article as it presents interpretation as opposed to strictly methods and data, but it is not speculation by the authors. Instead, this is where the authors combine their experience, background knowledge, and creativity to explain the data and use the data as evidence in their interpretation (see our Data Analysis and Interpretation module). Often, the discussion section includes several possible explanations or interpretations of the data; the authors may then describe why they support one particular interpretation over the others. This is not just a process of hedging their bets – this how scientists say to their peers that they have done their homework and that there is more than one possible explanation. In the woodpecker article, for example, the authors go to great lengths to describe why they believe the bird they saw is an ivory-billed woodpecker rather than a variant of the more common pileated woodpecker, knowing that this is a likely potential rebuttal to their initial findings. A final component of the conclusions involves placing the current work back into a larger context by discussing the implications of the work. The authors of the woodpecker article do so by discussing the nature of the woodpecker habitat and how it might be better preserved.

In many articles, the results and discussion sections are combined, but regardless, the data are initially presented without interpretation .

References: Scientific progress requires building on existing knowledge, and previous findings are recognized by directly citing them in any new work. The citations are collected in one list, commonly called "References," although the precise format for each journal varies considerably. The reference list may seem like something you don't actually read, but in fact it can provide a wealth of information about whether the authors are citing the most recent work in their field or whether they are biased in their citations towards certain institutions or authors. In addition, the reference section provides readers of the article with more information about the particular research topic discussed. The reference list for the woodpecker article includes a wide variety of sources that includes books, other journal articles, and personal accounts of bird sightings.

Supporting material: Increasingly, journals make supporting material that does not fit into the article itself – like extensive data tables, detailed descriptions of methods , figures, and animations – available online. In this case, the video footage shot by the authors is available online, along with several other resources.

- Reading the primary literature

The format of a scientific article may seem overly structured compared to many other things you read, but it serves a purpose by providing an archive of scientific research in the primary literature that we can build on. Though isolated examples of that archive go as far back as 600 BCE (see the Babylonian tablets in our Description in Scientific Research module), the first consistently published scientific journal was the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London , edited by Henry Oldenburg for the Royal Society beginning in 1666 (see our Scientific Institutions and Societies module). These early scientific writings include all of the components listed above, but the writing style is surprisingly different than a modern journal article. For example, Isaac Newton opened his 1672 article "New Theory About Light and Colours" with the following:

I shall without further ceremony acquaint you, that in the beginning of the Year 1666...I procured me a Triangular glass-Prisme, to try therewith the celebrated Phenomena of Colours . And in order thereto having darkened my chamber, and made a small hole in my window-shuts, to let in a convenient quantity of the Suns light, I placed my Prisme at his entrance, that it might be thereby refracted to the opposite wall. It was at first a very pleasing divertissement, to view the vivid and intense colours produced thereby; but after a while applying my self to consider them more circumspectly, I became surprised to see them in an oblong form; which, according to the received laws of Refraction, I expected should have been circular . (Newton, 1672)

Figure 4: Isaac Newton described the rainbow produced by a prism as a "pleasing divertissement."

Newton describes his materials and methods in the first few sentences ("... a small hole in my window-shuts"), describes his results ("an oblong form"), refers to the work that has come before him ("the received laws of Refraction"), and highlights how his results differ from his expectations. Today, however, Newton 's statement that the "colours" produced were a "very pleasing divertissement" would be out of place in a scientific article (Figure 4). Much more typically, modern scientific articles are written in an objective tone, typically without statements of personal opinion to avoid any appearance of bias in the interpretation of their results. Unfortunately, this tone often results in overuse of the passive voice, with statements like "a Triangular glass-Prisme was procured" instead of the wording Newton chose: "I procured me a Triangular glass-Prisme." The removal of the first person entirely from the articles reinforces the misconception that science is impersonal, boring, and void of creativity, lacking the enjoyment and surprise described by Newton. The tone can sometimes be misleading if the study involves many authors, making it unclear who did what work. The best scientific writers are able to both present their work in an objective tone and make their own contributions clear.

The scholarly vocabulary in scientific articles can be another obstacle to reading the primary literature. Materials and Methods sections often are highly technical in nature and can be confusing if you are not intimately familiar with the type of research being conducted. There is a reason for all of this vocabulary, however: An explicit, technical description of materials and methods provides a means for other scientists to evaluate the quality of the data presented and can often provide insight to scientists on how to replicate or extend the research described.

The tone and specialized vocabulary of the modern scientific article can make it hard to read, but understanding the purpose and requirements for each section can help you decipher the primary literature. Learning to read scientific articles is a skill, and like any other skill, it requires practice and experience to master. It is not, however, an impossible task.

Strange as it seems, the most efficient way to tackle a new article may be through a piecemeal approach, reading some but not all the sections and not necessarily in their order of appearance. For example, the abstract of an article will summarize its key points, but this section can often be dense and difficult to understand. Sometimes the end of the article may be a better place to start reading. In many cases, authors present a model that fits their data in this last section of the article. The discussion section may emphasize some themes or ideas that tie the story together, giving the reader some foundation for reading the article from the beginning. Even experienced scientists read articles this way – skimming the figures first, perhaps, or reading the discussion and then going back to the results. Often, it takes a scientist multiple readings to truly understand the authors' work and incorporate it into their personal knowledge base in order to build on that knowledge.

- Building knowledge and facilitating discussion

The process of science does not stop with the publication of the results of research in a scientific article. In fact, in some ways, publication is just the beginning. Scientific journals also provide a means for other scientists to respond to the work they publish; like many newspapers and magazines, most scientific journals publish letters from their readers.

Unlike the common "Letters to the Editor" of a newspaper, however, the letters in scientific journals are usually critical responses to the authors of a research study in which alternative interpretations are outlined. When such a letter is received by a journal editor, it is typically given to the original authors so that they can respond, and both the letter and response are published together. Nine months after the original publication of the woodpecker article, Science published a letter (called a "Comment") from David Sibley and three of his colleagues, who reinterpreted the Fitzpatrick team's data and concluded that the bird in question was a more common pileated woodpecker, not an ivory-billed woodpecker (Sibley et al., 2006). The team from the Cornell lab wrote a response supporting their initial conclusions, and Sibley's team followed that up with a response of their own in 2007 (Fitzpatrick et al., 2006; Sibley at al., 2007). As expected, the research has generated significant scientific controversy and, in addition, has captured the attention of the public, spreading the story of the controversy into the popular media.

For more information about this story see The Case of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker module.

Table of Contents

Activate glossary term highlighting to easily identify key terms within the module. Once highlighted, you can click on these terms to view their definitions.

Activate NGSS annotations to easily identify NGSS standards within the module. Once highlighted, you can click on them to view these standards.

Research Article vs. Research Paper

What's the difference.

A research article and a research paper are both scholarly documents that present the findings of a research study. However, there are some differences between the two. A research article is typically a shorter document that is published in a peer-reviewed journal. It focuses on a specific research question and provides a concise summary of the study's methodology, results, and conclusions. On the other hand, a research paper is usually a longer document that provides a more comprehensive analysis of a research topic. It often includes a literature review, detailed methodology, extensive data analysis, and a discussion of the implications of the findings. While both types of documents contribute to the scientific knowledge base, research papers tend to be more in-depth and provide a more thorough exploration of the research topic.

| Attribute | Research Article | Research Paper |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A written document that presents the findings of a research study or experiment. | A comprehensive written document that includes an in-depth analysis and interpretation of research findings. |

| Purpose | To communicate the results of a specific research study or experiment to the scientific community. | To provide a detailed analysis and interpretation of research findings, often including a literature review and methodology. |

| Length | Typically shorter, ranging from a few pages to around 20 pages. | Usually longer, ranging from 20 to hundreds of pages. |

| Structure | Usually follows a standard structure including sections such as abstract, introduction, methods, results, and conclusion. | May have a more flexible structure depending on the field and specific requirements, but often includes sections such as abstract, introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion. |

| Scope | Focuses on presenting the findings of a specific research study or experiment. | Explores a broader research topic or question, often including a literature review and analysis of multiple studies. |

| Publication | Can be published in academic journals, conference proceedings, or online platforms. | Can be published in academic journals, conference proceedings, or as part of a thesis or dissertation. |

| Peer Review | Research articles often undergo a peer review process before publication to ensure quality and validity. | Research papers may also undergo peer review, especially if published in academic journals. |

Further Detail

Introduction.

Research articles and research papers are both essential components of academic and scientific discourse. They serve as vehicles for sharing knowledge, presenting findings, and contributing to the advancement of various fields of study. While the terms "research article" and "research paper" are often used interchangeably, there are subtle differences in their attributes and purposes. In this article, we will explore and compare the key characteristics of research articles and research papers.

Definition and Purpose

A research article is a concise and focused piece of scholarly writing that typically appears in academic journals. It presents original research, experiments, or studies conducted by the author(s) and aims to communicate the findings to the scientific community. Research articles often follow a specific structure, including an abstract, introduction, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

On the other hand, a research paper is a broader term that encompasses various types of academic writing, including research articles. While research papers can also be published in journals, they can take other forms such as conference papers, dissertations, or theses. Research papers provide a more comprehensive exploration of a particular topic, often including a literature review, theoretical framework, and in-depth analysis of the research question.

Length and Depth

Research articles are typically shorter in length compared to research papers. They are usually limited to a specific word count, often ranging from 3000 to 8000 words, depending on the journal's guidelines. Due to their concise nature, research articles focus on presenting the core findings and their implications without delving extensively into background information or theoretical frameworks.

On the other hand, research papers tend to be longer and more comprehensive. They can range from 5000 to 20,000 words or more, depending on the scope of the research and the requirements of the academic institution or conference. Research papers provide a deeper analysis of the topic, including an extensive literature review, theoretical framework, and detailed methodology section.

Structure and Organization

Research articles follow a standardized structure to ensure clarity and consistency across different publications. They typically begin with an abstract, which provides a concise summary of the research question, methodology, results, and conclusions. The introduction section provides background information, states the research problem, and outlines the objectives of the study. The methodology section describes the research design, data collection methods, and statistical analysis techniques used. The results section presents the findings, often accompanied by tables, figures, or graphs. The discussion section interprets the results, compares them with previous studies, and discusses their implications. Finally, the conclusion summarizes the main findings and suggests future research directions.

Research papers, on the other hand, have a more flexible structure depending on the specific requirements of the academic institution or conference. While they may include similar sections as research articles, such as an abstract, introduction, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion, research papers can also incorporate additional sections such as a literature review, theoretical framework, or appendices. The structure of a research paper is often determined by the depth and complexity of the research conducted.

Publication and Audience

Research articles are primarily published in academic journals, which serve as platforms for disseminating new knowledge within specific disciplines. These journals often have a rigorous peer-review process, where experts in the field evaluate the quality and validity of the research before publication. Research articles are targeted towards a specialized audience of researchers, scholars, and professionals in the respective field.

Research papers, on the other hand, can be published in various formats and venues. They can be presented at conferences, published as chapters in books, or submitted as dissertations or theses. While research papers can also undergo peer-review, they may have a broader audience, including researchers, students, and professionals interested in the topic. The publication of research papers allows for a wider dissemination of knowledge beyond the confines of academic journals.

In conclusion, research articles and research papers are both vital components of academic and scientific discourse. While research articles are concise and focused pieces of scholarly writing that present original research findings, research papers provide a more comprehensive exploration of a particular topic. Research articles follow a standardized structure and are primarily published in academic journals, targeting a specialized audience. On the other hand, research papers have a more flexible structure and can be published in various formats, allowing for a wider dissemination of knowledge. Understanding the attributes and purposes of research articles and research papers is crucial for researchers, scholars, and students alike, as it enables effective communication and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in various fields.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

- Become Involved |

- Give to the Library |

- Staff Directory |

- UNF Library

- Thomas G. Carpenter Library

Article Types: What's the Difference Between Newspapers, Magazines, and Journals?

- Journal Articles

- Definitions

- Choosing What's Best

Journal Article Characteristics

- Magazine Articles

- Trade Magazine/Journal Articles

- Newspaper Articles

- Newsletter Articles

PMLA -- Publications of the Modern Language Association (an example of an academic journal)

Analyzing a Journal Article

Authors : Authors of journal articles are usually affiliated with universities, research institutions, or professional associations. Author degrees are usually specified with the author names, as are the affiliations.

Abstract : The article text is usually preceded with an abstract. The abstract will provide an overview of what the article discusses or reveals and frequently is useful in identifying articles that report the results of scientific studies. Use of Professional Terminology and Language: The language used in journal articles is specific to the subject matter being covered by the journal. For example, an article written for a psychological journal is written in an academic rather than popular style and will make heavy use of psychological terms.

In Text References : Journal articles normally will be profusely documented with sources that have provided information to the article authors and/or that provide further related information. Documentation of sources can be handled by in-text parenthetical references (MLA, APA, Chicago sciences styles), by the use of footnotes (Chicago humanities style), or by the use of endnotes (Turabian style). Individual journals will specify their own requirements for documentation.

Bibliography : Because journal articles use numerous sources as documentation, these sources are often referenced in an alphabetically or numerically arranged bibliography located at the end of the article. Format of the bibliography will vary depending on the documentation style used in the article.

Charts, Graphs, Tables, Statistical Data : Articles that result from research studies will often include statistical data gathered during the course of the studies. These data are often presented in charts and tables.

Length of Article : Journal articles, in general, tend to be fairly lengthy, often consisting of a dozen or more pages. Some journals also publish book reviews. These are typically brief and should not be confused with the full-length research articles that the journal focuses on.

Use of volume and issue numbering : Journals normally make use of volume and issue numbering to help identify individual issues in their series. Normally a volume will encompass an entire year's worth of a journal's issues. For example, a journal that is published four times yearly (quarterly) will have four issues in its yearly volume. Issues may be identified solely with numbers or with both numbers and date designations. For example, a quarterly journal will typically number its issues 1 through 4, but it might also assign season designations to the individual numbers, such as Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter. A monthly journal will have twelve issues in a yearly volume and might use the month names along with the issue numbers (issue 1, January; issue 2, February; and so on). Some magazines, trade publications, and newspapers might also make use of volume and issue numbering, so this isn't always the best indicator.

Subject Focus : Journals typically gather and publish research that focuses on a very specific field of inquiry, like criminology, or southern history, or statistics.

Overall Appearance : Journals are typically heavy on text and light on illustration. Journal covers tend toward the plain with an emphasis on highlighting key research articles that appear within a particular issue.

- << Previous: Choosing What's Best

- Next: Magazine Articles >>

- Last Updated: Aug 16, 2024 10:00 AM

- URL: https://libguides.unf.edu/articletypes

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

How do research papers differ from research articles? [duplicate]

What is the difference between a research paper and a research article? Frequently these two terms are considered in the same category. So, what features distinguish these two terms?

- publications

- terminology

- I always thought paper to be a kind of slang :) – Alchimista Commented Mar 24, 2019 at 12:12

2 Answers 2

Research article refers mainly to research published in a journal, whereas research paper refers to a research report whether it is a published one or not.

I don't think you will find a general definition that is universally applicable. But a research article could, in some cases, be a work that covers a number of papers, or the work of many people, and that attempts to bring ideas together, rather than to present fresh research itself.

A research paper, probably is more specific, presenting the work of some particular author(s) on a particular project.

Thus a research paper, presents an advancement in a field, whereas an article can be more general, not tied to a specific project, but generalizing a bit to give context to other work and bring it together.

But others can have different definitions, and this is just a personal observation. Your usage may vary. And I notice from other comments made here, that there are other views. Some will use the terms interchangeably, of course.

Not the answer you're looking for? Browse other questions tagged publications terminology .

- Featured on Meta

- Bringing clarity to status tag usage on meta sites

- We've made changes to our Terms of Service & Privacy Policy - July 2024

- Announcing a change to the data-dump process

Hot Network Questions

- Unreachable statement wen upgrading APEX class version

- Is It Possible to Assign Meaningful Amplitudes to Properties in Quantum Mechanics?

- ambobus? (a morphologically peculiar adjective with a peculiar syntax here)

- Dial “M” for murder

- Someone said 24-hour time for 0215 can be 零二么五小時 --- Why would 么 be used instead of 幺? Havent these 2 characters been different for nearly 70 years?

- Physical basis of "forced harmonics" on a violin

- Who became an oligarch after the collapse of the USSR

- What is the meaning of "Exit, pursued by a bear"?

- Is there a way to say "wink wink" or "nudge nudge" in German?

- How to read data from Philips P2000C over its serial port to a modern computer?

- How did Jason Bourne know the garbage man isn't CIA?

- Bottom bracket: What to do about rust in cup + blemish on spindle?

- Function to find the most common numeric ordered pairings (value, count)

- Simple JSON parser in lisp

- Is Hilbert's epsilon calculus a conservative extension of intuitionist logic?

- Were there mistakes in converting Dijkstra's Algol-60 compiler to Pascal?

- Is there a law against biohacking your pet?

- Using illustrations and comics in dissertations

- The complement of a properly embedded annulus in a handlebody is a handlebody

- Can police offer an “immune interview”?

- QGIS selecting multiple features per each feature, based on attribute value of each feature

- Symbol between two columns in a table

- Can I use "Member, IEEE" as my affiliation for publishing papers?

- Word to classify what powers a god is associated with?

Maxwell Library | Bridgewater State University

Today's Hours:

- Maxwell Library

- Scholarly Journals and Popular Magazines

- Differences in Research, Review, and Opinion Articles

Scholarly Journals and Popular Magazines: Differences in Research, Review, and Opinion Articles

- Where Do I Start?

- How Do I Find Peer-Reviewed Articles?

- How Do I Compare Periodical Types?

- Where Can I find More Information?

Research Articles, Reviews, and Opinion Pieces

Scholarly or research articles are written for experts in their fields. They are often peer-reviewed or reviewed by other experts in the field prior to publication. They often have terminology or jargon that is field specific. They are generally lengthy articles. Social science and science scholarly articles have similar structures as do arts and humanities scholarly articles. Not all items in a scholarly journal are peer reviewed. For example, an editorial opinion items can be published in a scholarly journal but the article itself is not scholarly. Scholarly journals may include book reviews or other content that have not been peer reviewed.

Empirical Study: (Original or Primary) based on observation, experimentation, or study. Clinical trials, clinical case studies, and most meta-analyses are empirical studies.

Review Article: (Secondary Sources) Article that summarizes the research in a particular subject, area, or topic. They often include a summary, an literature reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses.

Clinical case study (Primary or Original sources): These articles provide real cases from medical or clinical practice. They often include symptoms and diagnosis.

Clinical trials ( Health Research): Th ese articles are often based on large groups of people. They often include methods and control studies. They tend to be lengthy articles.

Opinion Piece: An opinion piece often includes personal thoughts, beliefs, or feelings or a judgement or conclusion based on facts. The goal may be to persuade or influence the reader that their position on this topic is the best.

Book review: Recent review of books in the field. They may be several pages but tend to be fairly short.

Social Science and Science Research Articles

The majority of social science and physical science articles include

- Journal Title and Author

- Abstract

- Introduction with a hypothesis or thesis

- Literature Review

- Methods/Methodology

- Results/Findings

Arts and Humanities Research Articles

In the Arts and Humanities, scholarly articles tend to be less formatted than in the social sciences and sciences. In the humanities, scholars are not conducting the same kinds of research experiments, but they are still using evidence to draw logical conclusions. Common sections of these articles include:

- an Introduction

- Discussion/Conclusion

- works cited/References/Bibliography

Research versus Review Articles

- 6 Article types that journals publish: A guide for early career researchers

- INFOGRAPHIC: 5 Differences between a research paper and a review paper

- Michigan State University. Empirical vs Review Articles

- UC Merced Library. Empirical & Review Articles

- << Previous: Where Do I Start?

- Next: How Do I Find Peer-Reviewed Articles? >>

- Last Updated: Jan 24, 2024 10:48 AM

- URL: https://library.bridgew.edu/scholarly

Phone: 508.531.1392 Text: 508.425.4096 Email: [email protected]

Feedback/Comments

Privacy Policy

Website Accessibility

Follow us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

- Georgia State University Library

- Help and Answers

Q. What's a scholarly journal, academic journal, or peer-reviewed journal?

- 22 About the Library

- 19 Borrowing Services

- 22 Business

- 17 Catalog (GIL-Find)

- 12 Citations

- 16 Computers, Wi-Fi & Software

- 27 Databases & GALILEO

- 15 Faculty & Graduate Students

- 6 iCollege & Online Students

- 7 Interlibrary Loan & GIL Express

- 6 Logging In & Passwords

- 8 Policies, Fines & Fees

- 9 Print, Copy & Scan

- 36 Research Help & Services

- 7 Reserves, Textbooks & OER

- 25 Spaces and Locations

- 15 Video & Film

Answered By: Mary Ann Cullen Last Updated: Jul 29, 2020 Views: 22092

"Scholarly Journal" and "Academic Journal" are two words for the same thing. Scholarly journals publish articles—usually articles about research—written by experts (scholars) in the field of study.

Usually, articles in these publications go through a "peer-review" process, which means other experts (peers) on the topic of the article weigh in on the quality of the article and the research it presents as well as the article's importance in their field of study. ( This video explains more ). Many professors will require you to use scholarly sources because they are more credible than articles published in popular magazines or on most websites.

Many databases label articles as being published in either a scholarly journal or a popular magazine . What's the difference?

For more help, ask a librarian.

updated 6/30/2020 kas

- Share on Facebook

Was this helpful? Yes 22 No 6

Comments (0)

Related topics.

- Research Help & Services

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Research Tips and Tools

Articles, Books and . . . ? Understanding the Many Types of Information Found in Libraries

- Reference Sources

Academic Journals

Magazines and trade journals, conference papers, technical reports, anthologies.

- Documents and Reports

- Non-Text Content

- Archival Materials

|

| Short works, anywhere from a paragraph up to about 30 pages, published as part of some larger work. |

Because of their short length, articles often exclude background info and explanations, so they're usually the last stop in your research process, after you've narrowed down your topic and need to find very specific information.

The main thing to remember about articles is that they're almost always published in some larger work , like a journal, a newspaper, or an anthology. It's those "article containers" that define the types of articles, how you use them, and how you find them.

Articles are also the main reason we have so many databases . The Library Catalog lists everything we own, but only at the level of whole books and journals. It will tell you we have the New York Times, and for what dates, but it doesn't know what articles are in it. Search in UC Library Search using the "Articles, books, and more" scope will search all the databases we subscribe to and some we don't. If you find something we do not own, you can request it on Interlibrary Loan.

Physical Media

While newer journals and magazines are usually online, many older issues are still only available in paper. In addition, many of our online subscriptions explicitly don't include the latest material, specifically to encourage sales of print subscriptions. Older newspapers are usually transferred to microfilm.

Scholarly Sources

The terms academic or scholarly journal are usually synonymous with peer-reviewed , but check the journal's publishing policies to be sure. Trade journals, magazines, and newspapers are rarely peer-reviewed.

Primary or Secondary Sources

In the social sciences and humanities, articles are usually secondary sources; the exceptions are articles reporting original research findings from field studies. Primary source articles are more common in the physical and life sciences, where many articles are reporting primary research results from experiments, case studies, and clinical trials.

Clues that you're reading an academic article

- Footnotes or endnotes

- Bilbliography or list of references

Articles in academic (peer-reviewed) journals are the primary forum for scholarly communication, where scholars introduce and debate new ideas and research. They're usually not written for laymen, and assume familiarity with other recent work in the field. Journal articles also tend to be narrowly focused, concentrating on analysis of one or two creative works or studies, though they may also contain review articles or literature reviews which summarize recent published work in a field.

In addition to regular articles, academic journals often include book reviews (of scholarly books ) and letters from readers commenting on recent articles.

Clues that you're reading a non -academic article

- Decorative photos

- Advertisements

Unlike scholarly journals, magazines are written for a mainstream audience and are not peer-reviewed. A handful of academic journals (like Science and Nature ) blur the line between these two categories; they publish peer-reviewed articles, but combine them with news, opinions, and full-color photos in a magazine-style presentation.

Trade journals are targeted toward a specific profession or industry. Despite the name, they are usually not peer-reviewed. However, they sometimes represent a gray area between popular magazines and scholarly journals. When in doubt, ask your professor or TA whether a specific source is acceptable.

Newspapers as Primary Sources

Though usually written by journalists who were not direct witnesses to events, newspapers and news broadcasts may include quotes or interviews from people who were. In the absence of first-person accounts, contemporary news reports may be the closest thing to a primary source available.

Of all the content types listed here, newspapers are the fastest to publish. Use newspaper articles to find information about recent events and contemporary reports of/reactions to historic events.

- News by UCLA Library Last Updated Aug 6, 2024 8885 views this year

Reviews are a type of article that can appear in any of the categories above. The type of publication will usually determine the type of review. Newspapers and magazines review movies, plays, general interest books, and consumer products. Academic journals review scholarly books.

Note that a review is not the same as scholarly analysis and criticism! Book reviews, even in scholarly journals, are usually not peer-reviewed.

| Review | Scholarly Criticism |

|---|---|

Conference papers aren't always published and can be tricky to find . Recent conference papers are often online, along with the PowerPoint files or other materials used in the actual presentation. However, access may be limited to conference participants and/or members of the academic organization which sponsored the conference.

In paper formats, all of the papers from a certain conference may be re-printed in the conference proceedings . Search for Proceedings of the [name of conference] to find what's available, or ask for help from a librarian. But be aware that published proceedings may only include abstracts or even just the name of the presenter and the title of the presentation. This is especially true of poster presentations , which really are large graphic posters (which don't translate well to either printed books or computer monitors).

As the name implies, most technical reports are about research in the physical sciences or engineering. However, there are also technical reports produced in the life and social sciences,

Like conference papers , some technical reports are eventually transformed into academic journal articles , but they may also be released after a journal article to provide supplementary data that didn't fit within the article. Also like conference papers, technical reports can be hard to find , especially older reports which may only be available in microfiche . Ask for help from a librarian!

Anthologies are a cross-over example. They're books that contain articles (chapters). Anthologies may be collections of articles by a single author, or collections of articles on a theme from different authors chosen by an editor. Many anthologies reprint articles already published elsewhere, but some contain original works.

Anthologies are rarely peer-reviewed, but they still may be considered scholarly works, depending on the reputation of the authors and editors. Use the same criteria listed for scholarly books .

Of course, reprints of articles originally published in peer-reviewed journals retain their "scholarly" status. (Note that most style manuals have special rules for citing reprinted works.)

- << Previous: Books

- Next: Documents and Reports >>

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 10:30 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/content-types

- About The Journalist’s Resource

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

White papers, working papers, preprints, journal articles: What’s the difference?

In this updated piece, we explain the most common types of research papers journalists will encounter, noting their strengths and weaknesses.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Denise-Marie Ordway, The Journalist's Resource February 25, 2022