Self-Presentation Theory (SPT)

Self-presentation theory: a review, introduction.

Self-presentation theory explains how individuals use verbal and non-verbal cues to project a particular image in society (Goffman, 1959). The theory draws on dramaturgy metaphors, such as backstage and frontstage, as a lens to explore human behaviour in everyday life (Goffman, 1959). Using dramaturgy as an analytical tool dates back to Nicholas Evreinov’s (1927) research on theatrical instincts, as well as Kenneth Burke’s (1969) work evaluating and scrutinising dramatic action (Shulman, 2016). Continuing this discourse, Erving Goffman (1959) offered a rich vein of theoretical concepts in sociology by drawing on theatre metaphors. While sociology research at that time focused on broader societal forces and structures, self-presentation theory emphasised individual behaviours and offered a lens to evaluate how performers interact with others to achieve personal goals (Goffman, 1959). Key to self-presentation theory is the notion of impression management and the routines that individuals play to manage an audience’s perception. As a result, self-presentation is crucial in developing one’s social identity. Thus, the theory paved the way for a better understanding of identity development through the performance acts of individuals in society.

Drawing on Goffman’s (1959) theorisation, self-presentation is defined as individuals’ actions to control, shape, and modify the impressions other people have of them in a particular setting. In other words, individuals’ " performance is socialised, moulded, and modified to fit into the understanding and expectations of the society in which it is presented " (Goffman, 1959:p44). Hence, self-presentation holds a strategic value to individuals as impressions influence how others assess, treat, and reward them (Leary & Kowalski, 1990). For instance, in a workplace setting, impressions may shape personal success and career progression (Gardner & Martinko, 1988).

Self-presentation theory draws on the traditions of symbolic interactionism (Blumer, 1986). Goffman suggests six key principles of the theory (Goffman, 1959; Shulman, 2016). First, individuals are performers who express their self to society. In practice, individuals highlight a persona and project a particular image to others. Such a projection is a means to show their identity and who they are to the society. Second, individuals want to put forward a credible image. They do so by being truthful and authentic in the way they present themselves. They showcase their expertise in a particular domain. Third, individuals take special care to avoid presenting themselves " out of character ". They strive to ensure that their performance or communication aligns with their role and identity in society. Fourth, if a performance is inadequate and not up to the mark, individuals address or repair it by engaging in restorative actions. Such actions ensure that their desired image is not tarnished. Fifth, self-presentation occurs in social places, known as regions of performance. Such regions in everyday life include the workplace, social gatherings, and social media. As such, they are "platforms" for self-presentation. Sixth, individuals work in teams and manage the impression of the collective to achieve common goals. In other words, a performance may not always occur alone, but can take place in concert with other individuals.

Individuals enact self-presentation because they are motivated to maximise rewards and minimise punishment (Leary & Kowalski, 1990;Schlenker, 1980). More specifically, motivations include the desire to (i) enhance self-esteem, (ii) develop a self-identity, and (iii) generate social and material benefits (Leary & Kowalski, 1990). In practice, people may strive to project an image that will result in praise and compliments, positively shaping one’s self-esteem (Leary & Kowalski, 1990). In contrast, individuals may avoid presenting an image that draws criticism and a lack of self-worth (Cohen, 1959). More specifically, a central motivation for self-presentation is to build an identity in society to foster a unique perception in the minds of others (Schlenker, 1980). Further, self-presentation is an adequate mechanism to foster rewards that can be social, including, trust, affection, and friendship. It can generate material benefits, such as financial gain (Leary & Kowalski, 1990).

Goffman (1959) uses the dramaturgical metaphor to explain the self-presentation theory and states that " the theatre metaphor is the ‘structure of the social encounter’ that occurs in all social life " (Adams & Sydie, 2002:p170). Drawing on dramaturgical metaphors, self-presentation comprises backstage and frontstage strategies akin to a theatre performance (Cho et al., 2018). These strategies are summarised in Table 1. Backstage relates to reflecting, practising, and taking adequate measures to prepare oneself (Goffman, 1959). Such practices occur in private and offer individuals a more comfortable atmosphere in which to prepare without the pressure from society, such as norms and expectations to behave in a certain way (Jeacle, 2014). The theory suggests the significance of rehearsal, which focuses on preparation work for the frontstage (Siegel, Tussyadiah & Scarles, 2023). For instance, individuals can practise and adjust their presentation at home before a formal client meeting.

Table 1: Self-presentation strategies

In contrast, frontstage comprises the " setting ", which includes the layout and objects in a particular room that set the scene for expression and action (Goffman, 1959). The setting is a place that is usually stable and unmovable, but at times can be relocated such as a circus (Goffman, 1959). Another key aspect of the frontstage is the " personal front ", which relates to personal characteristics such as sex, age, and facial expressions (Goffman, 1959). These characteristics are signals that are either fixed or vary over time (Goffman, 1959). Fixed characteristics are, for instance, one’s ethnic background, whereas characteristics that change include gestures based on one’s mood. The theory suggests that the personal front can be better understood through the lens of appearance and manner. The former relates to one’s temporal state such as work or leisure. The latter expresses the interaction role that one is likely to pursue in a given situation, like being professional and sincere (Goffman, 1959). Usually, there exists a coherence between the appearance and manner, although, at times, they may be misaligned (Goffman, 1959). For instance, a person of high status may behave in a way considered down to earth (Goffman, 1959).

Individuals can enact certain routines as part of their self-expression on the frontstage. At times, these routines can become institutionalised when an individual takes on specific roles in society (Goffman, 1959). The theory highlights the following routines: idealisation, mystification, self-promotion, exemplification, supplication, ingratiation, identification, basking in reflected glory, downward comparison, upward comparison, remaining silent, apology, and corrective action (Schütz, 1998).

Idealisation relates to individuals performing an ideal accredited impression in society (Goffman, 1959). Idealisation is common in social stratification research: individuals strive to go higher up the ladder in the social strata and adjust their self-presentations to reflect that ideal state and value system. In practice, individuals gain insight into the sign equipment required to showcase idealisation, and subsequently use it to project the accredited social class. Mystification is pursued by reducing contact and increasing social distance with the audience to create a sense of awe (Goffman, 1959). It is a means of limiting familiarity with others. For instance, mystification was used by Kings and Queens to foster an impression of power. The audience responded in a way that respected their mystic and sacred identity.

Self-promotion is pursued to create a credible image of oneself in the minds of others (Giacalone & Rosenfeld, 1986; Schau & Gilly, 2003). Such a form of persuasion is relevant in various circumstances, such as job interviews, influencer marketing, and presidential speeches. For instance, a candidate applying for a digital marketing role may share reflections on their expertise in search engine optimisation. An influencer focusing on health and fitness may share online videos of their exercise regimes. A presidential candidate may talk about their vast political experience to project their leadership qualities. Therefore, self-promotion focuses on projecting oneself as an expert and capable person in a particular domain (Bande et al., 2019). However, the theory suggests the issue of misrepresentation: behaviours that represent a false front (Goffman, 1959). Individuals may use credible vehicle signs for the wrong reasons, such as deception and fraud (Goffman, 1959).

Exemplification strategy focuses on creating an impression of oneself as virtuous and honourable (Bonner, Greenbaum & Quade, 2017; Gardner, 2003; Schütz, 1997). In other words, exemplification relates to creating an identity that rests on the notion of morality and ethics. For instance, Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) may publish posts on social media supporting charities, which projects a righteous image. Further, individuals regularly take a stand against harmful organisational behaviours, such as those engaging in child labour. While sharing their views on social media, those individuals exemplify a high moral ground and justify why organisations engaging in transgressions need to be held accountable. However, an exemplification strategy has its potential dangers. The society may question the motive behind such actions and consider it a means to cover up previous unethical deeds (Stone et al., 1997).

Supplication is based on showing oneself as vulnerable and frail to draw adequate support and help from others (Christopher et al., 2005; Korzynski, Haenlein & Rautiainen, 2021) . The ingratiation strategy relates to creating a likable and attractive impression in a particular place offline, such as one’s workplace, and online on social media (Bolino, Long & Turnley, 2016; Gross et al., 2021). For instance, an individual can project themselves to be professional and collegial in the workplace to foster goodwill and social approval.

The identification strategy puts emphasis on associating oneself with a particular community to create a specific image in society (Brewer & Gardner, 1996). For instance, some consumers may link themselves to the Harley-Davidson community to create a rebellious and adventurous image (Schembri, 2009). Tattoos, leather jackets, and riding on Harley motorcycles in packs reinforce their identification (Schembri, 2009). A strategy that slightly overlaps with identification work is " basking in reflected glor y" (Cialdini et al., 1976). In this case, an individual associates themselves with another person who has a positive impression in society and thus leverages those associations (Schütz, 1998).

Downward comparison focuses on projecting oneself as superior and in a positive light to the detriment of others (Wills, 1981). One may witness downward comparison in politics as one presidential candidate expresses how their vision and proposed policies are superior compared to another candidate. Upward comparison, however, is the practice of comparing oneself with someone better to improve one’s self-evaluations and perceptions (Collins, 1996).

Remaining silent may be a particular practice for individuals to be neutral and not face any criticism or backlash (Premeaux & Bedeian, 2003). Finally, particularly when one is responsible for an adverse event or has engaged in a wrong action, they may share an apology, defined as " repenting and promising moral behaviour in the future " (Hart, Tortoriello & Richardson, 2020:p2). They may suggest putting corrective measures in place so that it does not happen again in the future (Schütz, 1998).

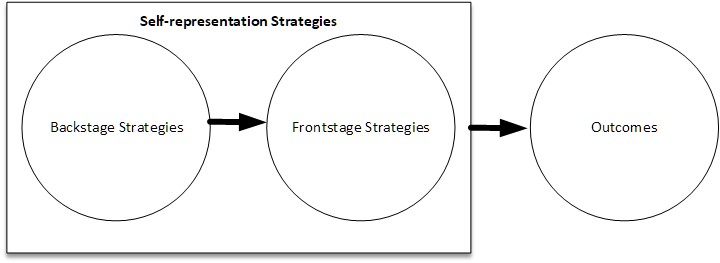

Figure 1 offers a generic framework of self-presentation theory, comprising frontstage and backstage strategies that help attain specific outcomes (Goffman, 1959; Leary & Kowalski, 1990). The backstage and frontstage are inter-related. Backstage strategies often involve preparation, desk research, and due diligence to gain insight into a particular performance (Jacobs, 1992). As such, backstage is an unofficial channel for individuals to gain the necessary skills, attributes, and contextual understanding to perform certain routines (Tiilikainen et al., 2024). Subsequently, individuals enact frontstage strategies involving those practised routines and impressions in a social context (Schütz, 1997).

To ensure adequate self-presentation, the theory suggests various means by which impression management can be pursued in the right way and includes defensive and protective practices (Goffman, 1959) as well as maintaining the definition of the situation (Tiilikainen et al., 2024). Defensive practices pursued by performers are a means for individuals and teams to safeguard their own performance. It requires discipline, whereby individuals have " presence of mind ". Disciplined individuals are resilient to unexpected circumstances and are sufficiently agile to ensure the performance attains its goal. In addition, individuals can enact circumspection by adequately preparing to offer a high-quality performance (Goffman, 1959). This involves taking time to design the performance and enacting foresight and prudence. Individuals may even show loyalty and devotion to other team members to ensure the overall impression does not fail (Goffman, 1959). When individuals reveal secrets or problems to outsiders, it damages the image of the team.

Protective practices, however, are pursued by audience members to help the performers manage their impressions (Goffman, 1959). They do so by not intruding on the back or frontstage. In practice, etiquette is maintained by not involving oneself in others' personal matters. Permission and consent are exercised to gain access. For instance, salespersons usually introduce themselves first and ask permission to discuss a product or service. However, the audience can exercise extra understanding and empathy when performance is not up to the mark for a person learning their trade (Goffman, 1959).

Finally, by maintaining a definition of the situation, individuals can develop an " agreed upon, subjective understanding of what will happen in a given situation or setting, and who will play which roles in the action " (Crossman, 2019). As a result, the concept defines the social order and gives symbolic meaning to human interactions that occur in everyday life (Tiilikainen et al., 2024). When the definition of the situation is not maintained or broken, the performance becomes ineffective and may even collapse (Tiilikainen et al., 2024).

Institutions shape how performers present themselves in everyday life. Goffman (1983:p1) used the terminology - interaction order – to explain the " loose coupling between interaction practices and social structure " and how " the workings of the interaction order can easily be viewed as the consequence of systems of enabling conventions, in the sense of ground rules for a game, the provisions of a traffic code or the rules of syntax of a language ". As such, the interaction order offers rules and norms that shape one’s behaviour in society. At an extreme level, institutions can have high levels of dominance and control, which Goffman (1961) defines as total institutions, which are often applied in prisons, military organisations, and even hospitals. Total institutions exert control over individuals’ daily routines, movements, and even identities (Goffman, 1961). The theoretical properties of total institutions include role dispossession i.e., " the process through which new recruits are prevented from being who they were in the world they inhabited prior to entry" (Shulman, 2016:p103). This involves trimming or programming, which relates to individuals being " shaped and coded into an object that can be fed into the administrative machinery of the establishment, to be worked on smoothly by routine operations " (Goffman, 1986:p16). Individuals in a total institution are forced to give up their identity kit i.e., personal belongings that give meaning to who they are in society (Shulman, 2016).

Theoretical developments

Since Goffman’s original work, scholars have advanced the theoretical properties of self-presentation. Specifically, in sharp contrast to total institutions, Scott (2011:p3) suggested the notion of reinventive institutions, defined as "a material, discursive or symbolic structure in which voluntary members actively seek to cultivate a new social identity, role or status. This is interpreted positively as a process of reinvention, self-improvement or transformation. It is achieved not only through formal instruction in an institutional rhetoric, but also through the mechanisms of performative regulation in the interaction context of an inmate culture" . Reinventive institutions are much more relevant in modern life, whereby individuals want to go through a transformation of their self and create a new identity (Scott, 2011). In other words, they want to let go of their previous self in pursuit of a reinvigorated new persona. Illustrative cases of reinventive institutions include spiritual communities and lifestyle groups (Shulman, 2016). Individuals are not forced to enter these communities; rather, they do so entirely voluntarily (Scott, 2010). These institutions are self-organising, i.e., the community members keep a check on each other to maintain the collective norms (Huber et al., 2020).

In contrast to Goffman’s original theorisation of self-presentation in face-to-face, offline interactions, research work has extended the theory to evaluate online impression management (Bareket-Bojmel, Moran & Shahar, 2016; Ranzini & Hoek, 2017; Rui & Stefanone, 2013). In practice, individuals use technology features such as text, images or videos to signal and manage their online image. This contrasts with non-verbal signals, such as body language, which are often common in offline interactions. Online impression management can be managed more conveniently as individuals can develop, change, or edit informational cues in a way that suits their purpose (Sun, Fang & Zhang, 2021). However, individuals’ digital footprint may remain over time online, and it can be viewed and accessed by others anytime (Hogan, 2010). This relates to the problem of " stage breach ", where data about individuals’ private lives are retrievable on search engines and social media platforms (Shulman, 2016). As such, the internet has caused the blurring of boundaries between back and frontstage, a phenomenon dubbed as " collapsed contexts " (Davis & Jurgenson, 2014), defined as " a flattening of the spatial, temporal, and social boundaries that otherwise separate audiences on social networking sites " (Duguay, 2016:p892). In response, individuals may use privacy filters or even delete content posted in the past that may negatively influence their image in society (DeAndrea, Tong & Lim, 2018).

Due to the advent of social media, Hogan (2010) extended Goffman’s theorisation by differentiating between "performances" and "exhibitions" that occur online. Performances, similar to Goffman’s dramaturgy metaphor, occur in real-time, such as in chat rooms, online meetings, and live streams. In this case, the situation is synchronous, and performances are time-bound (Hogan, 2010). However, exhibitions do not occur in real time, and individuals use technology artifacts afforded by social media to curate content (Hogan, 2010). These include posting a status update, uploading a photo album, or sharing a pre-recorded, edited video. As a result, exhibitions occur in asynchronous situations.

Overall, self-presentation theory provides a dramaturgy analytical lens for researchers to evaluate human behaviour in face-to-face and online interactions that involve synchronous and/or asynchronous situations. It offers a range of back and frontstage strategies that individuals and teams enact to manage their impressions in society, also suggesting that the broader institutional environment shapes how they behave in everyday life. Table 2 summarises the key conceptual definitions of self-presentation theory.

Table 2: Key concepts and definitions

Applications

Self-presentation theory is primarily anchored in sociology. However, other disciplines, such as management, marketing, and information systems, have extended the application of the theory in their respective contexts, such as work, social media, and branding. As such, the sociology discipline sheds light on the theoretical aspects of self-presentation, including its strategies, motivations, and application of the theory in everyday life (Goffman, 1959; Lewis & Neighbors, 2005; Schütz, 1998; Vohs, Baumeister & Ciarocco, 2005). Based on the theory, management scholars have investigated the application of self-presentation at work at two levels: individual and organisational (Bolino et al., 2008; Bolino & Turnley, 1999; Cook et al., 2024; Windscheid et al., 2018). At an individual level, self-presentation theory has been extensively applied to evaluate job interviews and performance appraisals (Kim et al., 2023; Moon et al., 2024). The theory is highly appropriate when determining individuals’ success or failure in securing work in organisations, as well as their job performance and career success (Gioaba & Krings, 2017; Bolino et al., 2008). For instance, leaders and managers who engage in appropriate self-presentation are more likely to generate " buy-in " and support from colleagues about their suggestions and action plans (Gardner & Martinko, 1988) . Research has even investigated how employees manage their impressions when interacting with colleagues on social media (Sun, Fang & Zhang, 2021; Ollier-Malaterre, Rothbard & Berg, 2013). This is crucial yet challenging because employees simultaneously have to manage their work and personal identities on social media (Ollier-Malaterre, Rothbard & Berg, 2013). In addition, research looked into how entrepreneurs managed their impression after the failure of their business (Kibler et al., 2021; Shepherd & Haynie, 2011). They do so to retain their credibility for future entrepreneurial ventures (Kibler et al., 2021).

At an organisational level, empirical work has examined organisational impression management (Benthaus, Risius & Beck, 2016; Carter, 2006; Schniederjans, Cao & Schniederjans, 2013). This is defined as " any action that is intentionally designed and carried out to influence an audience’s perceptions of the organisation " (Bolino et al., 2008:p1095). Studies have explored how organizational impression management strategies focus on assertive strategies to create a positive public image, such as sharing recent achievements (Mohamed, Gardner & Paolillo, 1999). In contrast, reactive strategies are used to manage crisis situations that tarnish the reputation of an organisation (Jin, Li & Hoskisson, 2022; Rim & Ferguson, 2020). Studies have also investigated how impression management of particular individuals (such as CEOs) shapes organisational image and performance (Cowen & Montgomery, 2020; Im, Kim & Miao, 2021). In contrast, research examined how organisational factors (e.g., culture) shape employee conduct in the workplace in a way that aligns with the values and norms expected in the organisation (Ashford et al., 1998).

In contemporary marketing, the metaphor of dramaturgy, which is central to impression management, has been used in retail and service research to investigate how to enhance customer experience (Bitner, 1992). In practice, the front and backstage have been effectively used to offer guidelines and implications to improve retail and service environments (Grove, Fisk & John, 2000). The marketing field even provides insight into how brands play a role in self-presentation (Ferraro, Kirmani & Matherly, 2013; Lee, Ko & Megehee, 2015). In particular, consumers often use and purchase brands that relate to a specific self-concept they strive to build and maintain (Jiménez-Barreto et al., 2022; Clark, Slama & Wolfe, 1999). In other words, brands offer consumers identity artifacts or props to express themselves. For instance, research by Jiménez-Barreto et al. (2022) finds that consumers find cool brands (original, iconic, and popular brands) valuable to construct their cool identity. This phenomenon is pertinent to luxury brands, which enable consumers to project a classy, high-status image in society (Kim & Oh, 2022). However, such consumer practices may backfire. Other people (or observers) may have negative perceptions of consumers using brands in a conspicuous or attention-seeking way (Ferraro, Kirmani & Matherly, 2013) and perceive them as having dark personalities, including narcissism, machiavellianism, and psychopathy (Razmus, Czarna & Fortuna, 2023). Observers even perceive consumers who use luxury brands to have lower levels of warmth (Cannon & Rucker, 2019). Managing impressions in marketing applies to buyer-seller relationships (Fisk & Grove, 1996). For example, sales professionals are often required to project an expert image. Impression management is also core to business-to-business marketing management, for instance, to remain resilient in crises (Alo et al., 2023; Lan & Sheng, 2023).

Information systems researchers have effectively investigated how technology can be used in the self-presentation process (Kim, Chan & Kankanhalli, 2012; Ma & Agarwal, 2007; Shi, Lai & Chen, 2023). The theoretical integration of self-presentation and technology is particularly relevant due to the advent of the internet, social media, metaverse, and artificial intelligence. For instance, Ma and Agarwal (2007) examined how technology artifacts afforded by virtual communities, such as avatars, nicknames, digital photographs and personal pages, enable users to enact self-presentation to create their identity. They find that when people have perceived verified identities, defined as " perceived confirmation from other community members of a focal person’s belief about (their) identities " (p. 46), it encourages the person to share knowledge with others in the virtual community. It even increases their satisfaction level with the community. Another study study found that the desire for online self-presentation, defined as the " extent to which an individual wants to present his or her preferred image in a virtual community of interest, " encourages individuals to purchase digital items, such as avatars and image files (Kim, Chan & Kankanhalli, 2012:p1235). These digital items are artifacts for self-expression and communication (Kim, Chan & Kankanhalli, 2012). The authors argue that the desire for online self-presentation in virtual communities is influenced by three factors: self-efficacy, norms, and involvement. They suggest that individuals who believe in their own capability to adequately develop a desired perception of themselves in the virtual community are more likely to engage in self-presentation work. Also, if the virtual community norms (rules and expectations) are conducive to self-presentation, the desire for self-presentation is stimulated. Further, if individuals are involved with the virtual community, i.e., they can relate to the community members, feel a strong affinity with them, and invest time and resources in the community, then it increases one’s desire for self-presentation. Chen and Chen (2020) suggest that the perceived value of those digital items encourages users to make a purchase. Yet in another study, Oh, Goh and Phan (2023) offer interesting insights and show that social media users are more inclined to share positive news to their network as part of their image-building process, as opposed to negative or controversial news. The reason is that sharing positive news reinforces one’s positive self-identity. In fact, such sharing behaviours are particularly relevant for users with a broader social network as they have a higher disposition to maintain a positive self-image (Oh, Goh & Phan, 2023).

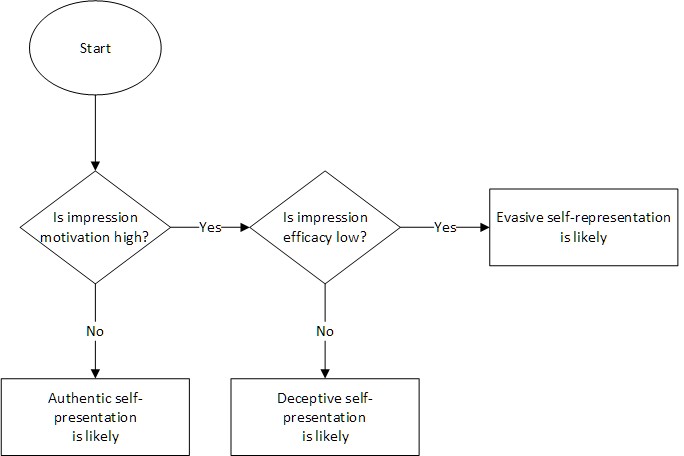

Self-presentation theory has been applied to effectively explore human deception (DeAndrea et al., 2012; Toma, Hancock & Ellison, 2008). Individuals may apply impression management strategies to falsely show themselves favourably to achieve their desired goals (Petrescu, Ajjan & Harrison, 2023). Research shows that individuals whose motivation to produce a positive impression in a group is low are likely to present themselves in an authentic way (Wooten & Reed, 2000). Similarly, if individuals are highly motivated to create a favourable image, they are not likely to use deception in a group unless they possess the self-efficacy to engage in deceptive work (Wooten & Reed, 2000). Meanwhile, those with low self-efficacy will probably pursue evasive self-presentation practices, such as stalling or repressing information (Wooten & Reed, 2000). Self-efficacy in the context of impression management means the extent to which an individual can control and manage their impression. It is subject to the requirements or demands of self-presentation in a particular social context, and the capabilities one possesses to achieve those demands (Schlenker & Leary, 1982). Figure 2 offers a framework that highlights deceptive self-presentation work in groups.

Importantly, with the advancements in digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence and deepfakes, individuals can develop content that may look real even though it is not (Mustak et al., 2023; Vasist & Krishnan, 2023). As a result, it has become extremely challenging to differentiate between authentic and fabricated content. This is further exacerbated as individuals can use digital tools, such as video filters, to project a misleading identity (Herring et al., 2024).

Limitations

Sociologists suggest that self-presentation theory, rooted in symbolic interactionism, focuses on micro-level interpretations of signs and meanings but offers a limited understanding of the broader societal factors and powers that influence individuals’ lives (Shulman, 2016). Moreover, management studies criticise the analytical ability of a theatre metaphor to explore impression management within organisations (Shulman, 2016). While self-presentation theory may be a useful framework, the extent to which a theatre’s characteristics relate to an organisation has been questioned (Shulman, 2016). This limitation is acknowledged by Goffman, who states in his book that " the perspective employed in this report is that of the theatrical performance; the principles derived are dramaturgical ones ... In using this model I will attempt not to make light of its obvious inadequacies. The stage presents things that are make-believe; presumably life presents things that are real ." (Goffman, 1959). Ongoing management research is attending to this limitation by investigating how employees manage their impression towards their co-workers and supervisors in organisations (Huang, Paterson & Wang, 2024).

Along the same lines, scholars have questioned the validity of a " performance " in self-presentation and whether such rituals are relevant in today’s society (Williams, 1986). The theory focuses on face-to-face interactions to manage impressions (Williams, 1986). Blumer (1972) suggests that the theory " stems from the narrowly constructed area of human group life ….limited the area of face-to-face association with a corresponding exclusion of the vast sum of human activity falling outside such association ." However, ongoing scholarly work is addressing this limitation by evaluating self-presentation in online environments, such as social media (Klostermann et al., 2023; Seidman, 2013). Self-presentation theory focuses heavily on the individual, and its applications to teams have received comparatively limited attention and extension (Blumer, 1972). As a result, recent research has looked into impression management on teamwork and team satisfaction (Schiller et al., 2024).

Scholars suggest that although Goffman’s conceptualisation of the interaction order offers a unique yet descriptive theoretical property, it provides limited knowledge of how the interaction order evolves over time and the explanatory variables that could suggest how and why the change occurred (Colomy & Brown, 1996). Importantly, Goffman’s conceptualisation of total institutions has received criticism in terms of its theoretical scope and generalisability, as not all organisations, such as mental hospitals, exert extreme control (Lemert, 1981). The total institution does not consider differences in " organisational goal, professional ideology, staff personality " (Weinstein, 1982:p269). Thus, research has looked into the application of impression management under different institutional environments, uncertainties in the business environment, and organisational motives (Ahmed, Elsayed & Xu, 2024; Busenbark, Lange & Certo, 2017).

Click to subscribe to our YouTube Channel.

Varqa Shamsi Bahar (Business School, Newcastle University)

How to Cite

Bahar, V.S. (2024) Self-Presentation Theory: A review . In S. Papagiannidis (Ed), TheoryHub Book . Available at https://open.ncl.ac.uk / ISBN: 9781739604400

Theory Profile

Discipline Psychology Unit of Analysis Individual, teams

Operationalised Qualitatively / Quantitatively Level Micro-level

Theory Tags

ISBN: 978-1-7396044-0-0

Published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

- About TheoryHub

- Submissions

- YouTube Channel

TheoryHub © 2020-2024 All rights reserved

Dr Manju Antil (Counselling Psychologist and Psychotherapist)

With a passion for understanding how the human mind works, I use my expertise as a Indian psychologist to help individuals nurture and develop their mental abilities to realize lifelong dreams. I am Dr Manju Antil working as a Counseling Psychologist and Psychotherapist at Wellnessnetic Care, will be your host in this journey. I will gonna share psychology-related articles, news and stories, which will gonna help you to lead your life more effectively. So are you excited? Let go

- Neurodevelopmental disorders

- Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders

- Bipolar and related disorders

- Depressive disorders

- Anxiety disorders

- Obsessive-compulsive and related disorders

- Trauma- and stressor-related disorders

- Dissociative disorders

- Somatic symptom and related disorders

- Feeding and eating disorders

- Elimination disorders

- Psychological therapies

- Sexual dysfunctions

- Gender dysphoria

- Disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders

- Substance-related and addictive disorders

- Neurocognitive disorders

- Personality disorders

- Applied Social Psychology

- Relationship Advice

- sociology and psychology

- Mind and Cognitive Process

- Rorschach Inkblot Test

- Counselling Psychology

- Free Psych Ebooks

- Video Gallery

- Psychology Today

- Appointment

- Take A Test

- Dr Manju Antil

- Photo Gallary

Goffman’s Self-Presentation Theory: Insights and Applications in Social Psychology| Applied Social Psychology| Dr Manju Rani

Erving Goffman’s self-presentation theory is a foundational concept in social psychology, offering insights into how individuals present themselves in everyday interactions. Goffman, a Canadian sociologist, introduced this theory in his seminal work The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1956), where he conceptualized social interactions as theatrical performances. This theory is a key framework for understanding how people consciously or unconsciously manage their image in social situations, depending on the context, audience, and desired outcomes.

1.1 Overview of Erving Goffman’s Contributions

Goffman’s contributions to sociology and psychology extended beyond self-presentation. His work touched on topics such as stigma, total institutions, and face-to-face communication. However, self-presentation remains one of his most enduring legacies. This concept plays a crucial role in applied social psychology, as it helps explain the underlying motivations behind human behaviour in various social contexts, from the workplace to social media interactions.

2. The Concept of Self-Presentation

At the heart of Goffman’s theory lies the idea that individuals are constantly performing for an audience, striving to control the impressions others form of them. This performance can vary based on the environment, audience, and specific social norms guiding the interaction.

2.1 The "Front Stage" and "Back Stage" Metaphor

Goffman introduced the metaphor of a theatrical performance to describe human interactions. The "front stage" refers to the public face that individuals present in social settings, while the "back stage" is where they retreat to prepare or relax away from the gaze of others. On the front stage, individuals perform roles that are shaped by the expectations of the audience and societal norms, while the back stage is reserved for moments of privacy where they can step out of their roles.

2.2 Impression Management as a Core Concept

Central to Goffman’s theory is the concept of impression management , which refers to the process by which individuals attempt to influence the perceptions of others. Whether consciously or unconsciously, people manage the impressions they create through their appearance, speech, body language, and actions. In applied social psychology, this concept is crucial for understanding how individuals navigate various social roles and relationships.

3. Key Elements of Self-Presentation Theory

Goffman’s theory includes several key elements that help explain how people present themselves and how these presentations are influenced by the social environment.

3.1 Social Roles and Social Scripts

In social interactions, individuals perform roles based on societal expectations, much like actors following a script. These social scripts provide guidelines for how to behave in specific situations, such as a job interview, a date, or a family gathering. Goffman’s theory highlights how people internalize and enact these roles, adjusting their performance based on feedback from others.

3.2 The Importance of Audience in Self-Presentation

Goffman emphasized the role of the audience in shaping self-presentation. Just as actors tailor their performances to fit the expectations of their audience, individuals modify their behavior based on the people they interact with. The same person may act differently in front of friends, colleagues, or strangers, depending on the social context and the desired outcome of the interaction.

3.3 Strategic Disclosure and Concealment of Information

Self-presentation often involves the strategic disclosure or concealment of information. Individuals may choose to highlight certain aspects of their identity or experience while downplaying or hiding others, depending on what will create the most favorable impression. For example, in a professional setting, one might emphasize their competence and reliability while concealing personal challenges.

4. Dramaturgy in Social Life

Goffman’s theatrical metaphor, known as dramaturgy , is a powerful tool for understanding social interactions. This perspective frames individuals as actors who use various strategies to present themselves to others.

4.1 The Theatrical Metaphor: Actors, Audience, and Props

In Goffman’s view, social life is like a stage where individuals are actors performing for an audience. The "props" in this performance can include clothing, accessories, or even language and gestures that help convey the desired image. These performances are often shaped by the setting and the roles people are expected to play.

4.2 Managing Impressions in Everyday Life

Goffman’s theory suggests that people are constantly managing impressions in their everyday lives, whether consciously or not. From the way they dress to how they speak, individuals aim to control how they are perceived by others. This constant management of impressions is a key part of navigating social life and maintaining relationships.

5. The Role of Social Norms in Self-Presentation

Social norms play a significant role in shaping how individuals present themselves. These unwritten rules guide behavior and define what is considered acceptable or unacceptable in different social contexts.

5.1 How Social Norms Guide Behavior in Different Contexts

Social norms vary depending on the situation, and individuals adjust their behavior accordingly. In formal settings, such as a business meeting, the norms may require a professional demeanor, while in informal settings, such as a casual gathering, the norms may allow for more relaxed behavior. Goffman’s theory emphasizes how these norms influence self-presentation.

5.2 Social Norms and Identity Performance

Identity performance is closely tied to social norms, as individuals often conform to these norms to fit into their social roles. For example, a teacher may adopt a formal and authoritative manner in the classroom, even if their natural personality is more relaxed. This adjustment is a form of impression management that aligns with societal expectations.

6. Applications of Self-Presentation in Social Psychology

Goffman’s self-presentation theory has wide-ranging applications in social psychology, particularly in understanding how people manage their image in different contexts.

6.1 Self-Presentation in Online Environments and Social Media

The rise of social media has brought new challenges and opportunities for self-presentation. In online environments, individuals have more control over the image they present, carefully curating their posts, photos, and interactions. However, the pressure to maintain a certain image can also lead to stress and anxiety, particularly when the online persona differs from the individual’s true self.

6.2 Self-Presentation in Professional Settings

In professional settings, impression management is crucial for career success. People often engage in self-promotion, emphasizing their skills, achievements, and qualifications to create a favorable impression on employers and colleagues. This strategic presentation is essential in job interviews, networking events, and workplace interactions.

6.3 Self-Presentation in Romantic and Friendship Relationships

In personal relationships, self-presentation plays a key role in forming connections. Individuals may present different aspects of their personality depending on the stage of the relationship and the desired outcome. For instance, early in a romantic relationship, people often highlight their best qualities while concealing less favorable traits.

7. The Psychological Impacts of Self-Presentation

While self-presentation can be a useful tool for navigating social interactions, it can also have psychological effects.

7.1 Effects of Self-Presentation on Self-Esteem

The need to constantly manage impressions can impact self-esteem, particularly when individuals feel that they are not living up to the image they present. This dissonance between the "front stage" self and the "back stage" self can lead to feelings of inadequacy and self-doubt.

7.2 Anxiety and Cognitive Dissonance in Self-Presentation

The pressure to maintain a certain image can also cause anxiety, especially in situations where individuals fear that their true self will be revealed. Cognitive dissonance, the discomfort caused by holding conflicting beliefs or behaviors, can arise when the image a person presents does not align with their internal sense of self.

8. Impression Management Techniques

Individuals use various strategies to manage the impressions they create. Goffman identified several common techniques in his analysis of self-presentation.

8.1 Ingratiation

Ingratiation involves using flattery or other forms of positive reinforcement to gain favor with others. People often use this technique to appear more likable or cooperative, particularly in situations where they want to be accepted by a group.

8.2 Self-Promotion

Self-promotion is a strategy where individuals emphasize their accomplishments and positive qualities to create a favorable impression. This technique is common in professional settings, where individuals seek to showcase their competence and expertise.

8.3 Supplication and Exemplification

Supplication involves presenting oneself as needy or vulnerable to gain sympathy or help from others. Exemplification, on the other hand, involves demonstrating integrity and high moral standards to earn respect and admiration.

9. Self-Presentation and Social Identity Theory

Goffman’s self-presentation theory can be linked to social identity theory, which explores how individuals derive their sense of self from their group memberships.

9.1 Linking Goffman’s Ideas to Social Identity Theory

Social identity theory, developed by Henri Tajfel, suggests that people identify with certain social groups and derive part of their self-concept from these affiliations. Goffman’s theory complements this by explaining how individuals present themselves in ways that align with their group identities, managing impressions to fit in with group norms.

9.2 Identity, Group Membership, and Social Roles

In applied social psychology, Goffman’s ideas help explain how individuals navigate the tension between personal identity and group membership. People often adjust their self-presentation to align with the expectations of their social groups, whether in the workplace, at home, or in social gatherings.

10. Criticisms of Self-Presentation Theory

Despite its influential status, Goffman’s self-presentation theory has faced some criticisms.

10.1 Overemphasis on Social Performance

Critics argue that Goffman’s theory places too much emphasis on the performative aspects of social interaction, suggesting that all behavior is a calculated performance. This perspective may overlook more spontaneous or genuine aspects of human behavior that do not involve conscious impression management.

10.2 Limitations in Addressing Non-Conscious Behavior

Another criticism is that Goffman’s theory does not adequately address non-conscious behaviors. Many social interactions involve automatic, habitual behaviors that do not involve conscious impression management, which is not fully accounted for in the dramaturgical framework.

11. Case Studies of Self-Presentation in Social Psychology

Several case studies highlight how Goffman’s self-presentation theory applies to real-world social interactions.

11.1 Workplace Scenarios: Managing Professional Image

In workplace settings, individuals often engage in impression management to navigate professional relationships. For example, employees may present themselves as competent and dedicated to gain the trust of their superiors, while also managing their image among colleagues.

11.2 Political Leaders and Public Perception

Political leaders are constantly engaged in self-presentation, as their public image plays a crucial role in their success. They often craft speeches, public appearances, and social media profiles to create a favorable impression on their audience.

11.3 Social Media Influencers and Digital Impression Management

Social media influencers provide a modern example of Goffman’s self-presentation theory in action. Influencers carefully curate their online personas to attract followers, using a range of strategies to manage their image and maintain engagement with their audience.

12. Cultural Influences on Self-Presentation

Self-presentation is not universal; it varies significantly across cultures, influenced by different social norms and values.

12.1 Variations in Self-Presentation Across Cultures

Cultural norms play a key role in shaping how individuals present themselves. In collectivist cultures, for example, self-presentation may emphasize group harmony and conformity, while in individualistic cultures, people may focus more on personal achievement and uniqueness.

12.2 Cross-Cultural Research and Goffman’s Theory

Cross-cultural research in social psychology has explored how Goffman’s ideas apply in different cultural contexts. These studies have found that while the basic principles of self-presentation hold across cultures, the specific strategies and norms guiding behaviour can vary widely.

13. The Evolution of Self-Presentation in a Digital Age

The rise of digital communication has transformed self-presentation, creating new opportunities and challenges for managing impressions.

13.1 Changing Dynamics in Virtual Environments

In online environments, individuals have greater control over their self-presentation, but they also face new pressures. The ability to edit and curate digital content allows for more deliberate impression management, but it can also lead to a disconnect between one’s online persona and real-life identity.

13.2 Social Media and the Performance of Multiple Selves

Social media platforms enable individuals to present different versions of themselves to different audiences. For example, someone might present a professional image on LinkedIn, while maintaining a more casual or playful persona on Instagram. This ability to manage multiple selves is a key aspect of digital self-presentation.

14. Ethical Considerations in Self-Presentation

The strategic nature of self-presentation raises important ethical questions, particularly around issues of authenticity and deception.

14.1 Authenticity vs. Deception in Social Interactions

One of the central ethical dilemmas in self-presentation is the balance between authenticity and deception. While it is natural to present oneself in a favorable light, there is a fine line between managing impressions and misleading others. This is particularly relevant in online environments, where individuals can easily manipulate their image.

14.2 Ethical Boundaries in Managing Impressions

In professional and personal relationships, maintaining ethical boundaries in impression management is crucial. Overemphasizing certain qualities or concealing important information can lead to mistrust and damaged relationships, highlighting the importance of transparency in social interactions.

15. Conclusion

Erving Goffman’s self-presentation theory remains a powerful framework for understanding social interactions and the ways individuals manage their image in different contexts. From everyday encounters to the complexities of social media, the theory provides valuable insights into how people navigate the expectations of others while maintaining their sense of self.

15.1 Revisiting Goffman’s Influence on Social Psychology

Goffman’s work continues to influence the field of social psychology, particularly in the study of social identity, group dynamics, and online behavior. His theory provides a useful lens for exploring the nuances of human behavior and the ways people adapt to different social roles and expectations.

15.2 The Future of Self-Presentation Research

As technology continues to evolve, so too will the study of self-presentation. Future research may focus on how digital environments shape self-presentation strategies and the psychological effects of maintaining multiple personas across different platforms. Goffman’s insights will remain relevant as scholars continue to explore the complexities of social behavior in an increasingly interconnected world.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Book your appointment with Dr Manju Antil

- Photo Gallery (Dr. Manju Antil)| Wellnessnetic Care

CLICK HERE FOR OUR LATEST UPDATE

Popular Posts

SUBSCRIBE AND GET LATEST UPDATES

Search This Blog

- Blog Archives

- FACTORS AFFECTING ADJUSTMENT Henry Smith (1961) in a conclusive statement stated that a good adjustment is one that is both realistic and satisfactory. At least in the l...

- Book Appointment

- BTS Updates

- Clinical Psychology

- Counseling Psychology

- Depressive disorder

- Disruptive impulse-control and conduct disorders

- Health Alert

- Human Behaviour

- Mental Health

- Mental Health Intake Form

- Mind and Cognitive Processes

- Paraphilic disorders

- Personality

- Personality Assessment

- Psychology Jobs

- Psychology Notes

- Psychotherapy

- Sleep and wake disorders

- Somatic symptoms and related disorders

- Special Disabilities

- Substance related and addictive disorder

- Take a Test

- Trending Topic

- UGC Net Psychology

Connect With Us On Social Media

Featured post, non-specific variables in therapy: a comprehensive overview| meaning of non-specific variables in therapy.

Non-specific variables in therapy refer to elements of the therapeutic process that influence the outcomes of treatment but are not direct...

Subscribe To

Most trending.

- Anxiety disorders (7)

- Applied Social Psychology (20)

- Bipolar and related disorders (5)

- Book Appointment (4)

- BTS Updates (9)

- Clinical Psychology (63)

- Counseling Psychology (84)

- Creativity (18)

- Depressive disorder (12)

- Disruptive impulse-control and conduct disorders (1)

- Dissociative disorders (1)

- Elimination disorders (1)

- Feeding and eating disorders (1)

- Gender dysphoria (1)

- Health Alert (28)

- Human Behaviour (122)

- Law School (3)

- Mental Health (57)

- Mental Health Intake Form (6)

- Mind and Cognitive Processes (85)

- Neurodevelopmental disorders (2)

- Obsessive-compulsive and related disorders (1)

- Paraphilic disorders (1)

- Personality (35)

- Personality Assessment (23)

- Personality disorders (1)

- Psychological therapies (28)

- Psychology Jobs (10)

- Psychology Notes (63)

- Psychology Today (114)

- Psychotherapy (11)

- Relationship Advice (30)

- Rorschach Inkblot Test (7)

- Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders (1)

- Sexual dysfunctions (2)

- Sleep and wake disorders (2)

- sociology and psychology (74)

- Somatic symptoms and related disorders (1)

- Special Disabilities (9)

- Substance related and addictive disorder (1)

- Take a Test (13)

- Trauma- and stressor-related disorders (1)

- Trending Topic (101)

- UGC Net Psychology (68)

- Video Gallery (4)

- Psychologist Manju Antil

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Wellnessnetic Care (Mental Health Intake Form)

Blog Archive

- ► December (86)

- ► November (12)

- Therapy Types: Supportive, Re-educative, and Recon...

- Understanding Hopelessness Theory: Treatment and P...

- Types of Learning and Proven Methods: A Comprehens...

- Goffman’s Self-Presentation Theory: Insights and A...

- Emotions: Definition, Differentiation, and Mechani...

- Understanding Motivation: A Key to Human Behavior|...

- Social Psychological Roots of Social Anxiety and D...

- Navigating Self-Presentation and Hopelessness: The...

- Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)| Applied Social P...

- Origins of Psychological Disorders in the Context ...

- Health Belief Model (HBM) in the Context of Social...

- Groupthink: The Double-Edged Sword of Team Cohesio...

- ► September (16)

- ► July (17)

- ► June (4)

- ► April (1)

- ► March (1)

- ► February (1)

- ► January (3)

- ► December (7)

- ► November (2)

- ► October (1)

- ► September (5)

- ► August (4)

- ► July (7)

- ► June (12)

- ► May (23)

- ► April (36)

- ► March (11)

- ► February (17)

- ► January (11)

- ► December (16)

- ► November (9)

- ► October (3)

- ► August (8)

- ► May (3)

- ► February (3)

- ► January (14)

- ► December (15)

- ► November (3)

- ► October (4)

- ► September (1)

- ► August (6)

- ► July (25)

Contact Form

- Term and Condition

IMAGES

VIDEO