Grab Your Free Copy of The State of Leadership Development Report 2024

Heuristic Problem Solving: A comprehensive guide with 5 Examples

What are heuristics, advantages of using heuristic problem solving, disadvantages of using heuristic problem solving, heuristic problem solving examples, frequently asked questions.

- Speed: Heuristics are designed to find solutions quickly, saving time in problem solving tasks. Rather than spending a lot of time analyzing every possible solution, heuristics help to narrow down the options and focus on the most promising ones.

- Flexibility: Heuristics are not rigid, step-by-step procedures. They allow for flexibility and creativity in problem solving, leading to innovative solutions. They encourage thinking outside the box and can generate unexpected and valuable ideas.

- Simplicity: Heuristics are often easy to understand and apply, making them accessible to anyone regardless of their expertise or background. They don’t require specialized knowledge or training, which means they can be used in various contexts and by different people.

- Cost-effective: Because heuristics are simple and efficient, they can save time, money, and effort in finding solutions. They also don’t require expensive software or equipment, making them a cost-effective approach to problem solving.

- Real-world applicability: Heuristics are often based on practical experience and knowledge, making them relevant to real-world situations. They can help solve complex, messy, or ill-defined problems where other problem solving methods may not be practical.

- Potential for errors: Heuristic problem solving relies on generalizations and assumptions, which may lead to errors or incorrect conclusions. This is especially true if the heuristic is not based on a solid understanding of the problem or the underlying principles.

- Limited scope: Heuristic problem solving may only consider a limited number of potential solutions and may not identify the most optimal or effective solution.

- Lack of creativity: Heuristic problem solving may rely on pre-existing solutions or approaches, limiting creativity and innovation in problem-solving.

- Over-reliance: Heuristic problem solving may lead to over-reliance on a specific approach or heuristic, which can be problematic if the heuristic is flawed or ineffective.

- Lack of transparency: Heuristic problem solving may not be transparent or explainable, as the decision-making process may not be explicitly articulated or understood.

- Trial and error: This heuristic involves trying different solutions to a problem and learning from mistakes until a successful solution is found. A software developer encountering a bug in their code may try other solutions and test each one until they find the one that solves the issue.

- Working backward: This heuristic involves starting at the goal and then figuring out what steps are needed to reach that goal. For example, a project manager may begin by setting a project deadline and then work backward to determine the necessary steps and deadlines for each team member to ensure the project is completed on time.

- Breaking a problem into smaller parts: This heuristic involves breaking down a complex problem into smaller, more manageable pieces that can be tackled individually. For example, an HR manager tasked with implementing a new employee benefits program may break the project into smaller parts, such as researching options, getting quotes from vendors, and communicating the unique benefits to employees.

- Using analogies: This heuristic involves finding similarities between a current problem and a similar problem that has been solved before and using the solution to the previous issue to help solve the current one. For example, a salesperson struggling to close a deal may use an analogy to a successful sales pitch they made to help guide their approach to the current pitch.

- Simplifying the problem: This heuristic involves simplifying a complex problem by ignoring details that are not necessary for solving it. This allows the problem solver to focus on the most critical aspects of the problem. For example, a customer service representative dealing with a complex issue may simplify it by breaking it down into smaller components and addressing them individually rather than simultaneously trying to solve the entire problem.

Test your problem-solving skills for free in just a few minutes.

The free problem-solving skills for managers and team leaders helps you understand mistakes that hold you back.

What are the three types of heuristics?

What are the four stages of heuristics in problem solving.

Other Related Blogs

Top 15 Tips for Effective Conflict Mediation at Work

Top 10 games for negotiation skills to make you a better leader, manager effectiveness: a complete guide for managers in 2024, 5 proven ways managers can build collaboration in a team.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Are Heuristics?

These mental shortcuts lead to fast decisions—and biased thinking

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

Verywell / Cindy Chung

- History and Origins

- Heuristics vs. Algorithms

- Heuristics and Bias

How to Make Better Decisions

If you need to make a quick decision, there's a good chance you'll rely on a heuristic to come up with a speedy solution. Heuristics are mental shortcuts that allow people to solve problems and make judgments quickly and efficiently. Common types of heuristics rely on availability, representativeness, familiarity, anchoring effects, mood, scarcity, and trial-and-error.

Think of these as mental "rule-of-thumb" strategies that shorten decision-making time. Such shortcuts allow us to function without constantly stopping to think about our next course of action.

However, heuristics have both benefits and drawbacks. These strategies can be handy in many situations but can also lead to cognitive biases . Becoming aware of this might help you make better and more accurate decisions.

Press Play for Advice On Making Decisions

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares a simple way to make a tough decision. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

History of the Research on Heuristics

Nobel-prize winning economist and cognitive psychologist Herbert Simon originally introduced the concept of heuristics in psychology in the 1950s. He suggested that while people strive to make rational choices, human judgment is subject to cognitive limitations. Purely rational decisions would involve weighing every alternative's potential costs and possible benefits.

However, people are limited by the amount of time they have to make a choice and the amount of information they have at their disposal. Other factors, such as overall intelligence and accuracy of perceptions, also influence the decision-making process.

In the 1970s, psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman presented their research on cognitive biases. They proposed that these biases influence how people think and make judgments.

Because of these limitations, we must rely on mental shortcuts to help us make sense of the world.

Simon's research demonstrated that humans were limited in their ability to make rational decisions, but it was Tversky and Kahneman's work that introduced the study of heuristics and the specific ways of thinking that people rely on to simplify the decision-making process.

How Heuristics Are Used

Heuristics play important roles in both problem-solving and decision-making , as we often turn to these mental shortcuts when we need a quick solution.

Here are a few different theories from psychologists about why we rely on heuristics.

- Attribute substitution : People substitute simpler but related questions in place of more complex and difficult questions.

- Effort reduction : People use heuristics as a type of cognitive laziness to reduce the mental effort required to make choices and decisions.

- Fast and frugal : People use heuristics because they can be fast and correct in certain contexts. Some theories argue that heuristics are actually more accurate than they are biased.

In order to cope with the tremendous amount of information we encounter and to speed up the decision-making process, our brains rely on these mental strategies to simplify things so we don't have to spend endless amounts of time analyzing every detail.

You probably make hundreds or even thousands of decisions every day. What should you have for breakfast? What should you wear today? Should you drive or take the bus? Fortunately, heuristics allow you to make such decisions with relative ease and without a great deal of agonizing.

There are many heuristics examples in everyday life. When trying to decide if you should drive or ride the bus to work, for instance, you might remember that there is road construction along the bus route. You realize that this might slow the bus and cause you to be late for work. So you leave earlier and drive to work on an alternate route.

Heuristics allow you to think through the possible outcomes quickly and arrive at a solution.

Are Heuristics Good or Bad?

Heuristics aren't inherently good or bad, but there are pros and cons to using them to make decisions. While they can help us figure out a solution to a problem faster, they can also lead to inaccurate judgments about others or situations. Understanding these pros and cons may help you better use heuristics to make better decisions.

Types of Heuristics

There are many different kinds of heuristics. While each type plays a role in decision-making, they occur during different contexts. Understanding the types can help you better understand which one you are using and when.

Availability

The availability heuristic involves making decisions based upon how easy it is to bring something to mind. When you are trying to make a decision, you might quickly remember a number of relevant examples.

Since these are more readily available in your memory, you will likely judge these outcomes as being more common or frequently occurring.

For example, imagine you are planning to fly somewhere on vacation. As you are preparing for your trip, you might start to think of a number of recent airline accidents. You might feel like air travel is too dangerous and decide to travel by car instead. Because those examples of air disasters came to mind so easily, the availability heuristic leads you to think that plane crashes are more common than they really are.

Familiarity

The familiarity heuristic refers to how people tend to have more favorable opinions of things, people, or places they've experienced before as opposed to new ones. In fact, given two options, people may choose something they're more familiar with even if the new option provides more benefits.

Representativeness

The representativeness heuristic involves making a decision by comparing the present situation to the most representative mental prototype. When you are trying to decide if someone is trustworthy, you might compare aspects of the individual to other mental examples you hold.

A soft-spoken older woman might remind you of your grandmother, so you might immediately assume she is kind, gentle, and trustworthy. However, this is an example of a heuristic bias, as you can't know someone trustworthy based on their age alone.

The affect heuristic involves making choices that are influenced by an individual's emotions at that moment. For example, research has shown that people are more likely to see decisions as having benefits and lower risks when in a positive mood.

Negative emotions, on the other hand, lead people to focus on the potential downsides of a decision rather than the possible benefits.

The anchoring bias involves the tendency to be overly influenced by the first bit of information we hear or learn. This can make it more difficult to consider other factors and lead to poor choices. For example, anchoring bias can influence how much you are willing to pay for something, causing you to jump at the first offer without shopping around for a better deal.

Scarcity is a heuristic principle in which we view things that are scarce or less available to us as inherently more valuable. Marketers often use the scarcity heuristic to influence people to buy certain products. This is why you'll often see signs that advertise "limited time only," or that tell you to "get yours while supplies last."

Trial and Error

Trial and error is another type of heuristic in which people use a number of different strategies to solve something until they find what works. Examples of this type of heuristic are evident in everyday life.

People use trial and error when playing video games, finding the fastest driving route to work, or learning to ride a bike (or any new skill).

Difference Between Heuristics and Algorithms

Though the terms are often confused, heuristics and algorithms are two distinct terms in psychology.

Algorithms are step-by-step instructions that lead to predictable, reliable outcomes, whereas heuristics are mental shortcuts that are basically best guesses. Algorithms always lead to accurate outcomes, whereas, heuristics do not.

Examples of algorithms include instructions for how to put together a piece of furniture or a recipe for cooking a certain dish. Health professionals also create algorithms or processes to follow in order to determine what type of treatment to use on a patient.

How Heuristics Can Lead to Bias

Heuristics can certainly help us solve problems and speed up our decision-making process, but that doesn't mean they are always a good thing. They can also introduce errors, bias, and irrational decision-making. As in the examples above, heuristics can lead to inaccurate judgments about how commonly things occur and how representative certain things may be.

Just because something has worked in the past does not mean that it will work again, and relying on a heuristic can make it difficult to see alternative solutions or come up with new ideas.

Heuristics can also contribute to stereotypes and prejudice . Because people use mental shortcuts to classify and categorize people, they often overlook more relevant information and create stereotyped categorizations that are not in tune with reality.

While heuristics can be a useful tool, there are ways you can improve your decision-making and avoid cognitive bias at the same time.

We are more likely to make an error in judgment if we are trying to make a decision quickly or are under pressure to do so. Taking a little more time to make a decision can help you see things more clearly—and make better choices.

Whenever possible, take a few deep breaths and do something to distract yourself from the decision at hand. When you return to it, you may find a fresh perspective or notice something you didn't before.

Identify the Goal

We tend to focus automatically on what works for us and make decisions that serve our best interest. But take a moment to know what you're trying to achieve. Consider some of the following questions:

- Are there other people who will be affected by this decision?

- What's best for them?

- Is there a common goal that can be achieved that will serve all parties?

Thinking through these questions can help you figure out your goals and the impact that these decisions may have.

Process Your Emotions

Fast decision-making is often influenced by emotions from past experiences that bubble to the surface. Anger, sadness, love, and other powerful feelings can sometimes lead us to decisions we might not otherwise make.

Is your decision based on facts or emotions? While emotions can be helpful, they may affect decisions in a negative way if they prevent us from seeing the full picture.

Recognize All-or-Nothing Thinking

When making a decision, it's a common tendency to believe you have to pick a single, well-defined path, and there's no going back. In reality, this often isn't the case.

Sometimes there are compromises involving two choices, or a third or fourth option that we didn't even think of at first. Try to recognize the nuances and possibilities of all choices involved, instead of using all-or-nothing thinking .

Heuristics are common and often useful. We need this type of decision-making strategy to help reduce cognitive load and speed up many of the small, everyday choices we must make as we live, work, and interact with others.

But it pays to remember that heuristics can also be flawed and lead to irrational choices if we rely too heavily on them. If you are making a big decision, give yourself a little extra time to consider your options and try to consider the situation from someone else's perspective. Thinking things through a bit instead of relying on your mental shortcuts can help ensure you're making the right choice.

Vlaev I. Local choices: Rationality and the contextuality of decision-making . Brain Sci . 2018;8(1):8. doi:10.3390/brainsci8010008

Hjeij M, Vilks A. A brief history of heuristics: how did research on heuristics evolve? Humanit Soc Sci Commun . 2023;10(1):64. doi:10.1057/s41599-023-01542-z

Brighton H, Gigerenzer G. Homo heuristicus: Less-is-more effects in adaptive cognition . Malays J Med Sci . 2012;19(4):6-16.

Schwartz PH. Comparative risk: Good or bad heuristic? Am J Bioeth . 2016;16(5):20-22. doi:10.1080/15265161.2016.1159765

Schwikert SR, Curran T. Familiarity and recollection in heuristic decision making . J Exp Psychol Gen . 2014;143(6):2341-2365. doi:10.1037/xge0000024

AlKhars M, Evangelopoulos N, Pavur R, Kulkarni S. Cognitive biases resulting from the representativeness heuristic in operations management: an experimental investigation . Psychol Res Behav Manag . 2019;12:263-276. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S193092

Finucane M, Alhakami A, Slovic P, Johnson S. The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits . J Behav Decis Mak . 2000; 13(1):1-17. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0771(200001/03)13:1<1::AID-BDM333>3.0.CO;2-S

Teovanović P. Individual differences in anchoring effect: Evidence for the role of insufficient adjustment . Eur J Psychol . 2019;15(1):8-24. doi:10.5964/ejop.v15i1.1691

Cheung TT, Kroese FM, Fennis BM, De Ridder DT. Put a limit on it: The protective effects of scarcity heuristics when self-control is low . Health Psychol Open . 2015;2(2):2055102915615046. doi:10.1177/2055102915615046

Mohr H, Zwosta K, Markovic D, Bitzer S, Wolfensteller U, Ruge H. Deterministic response strategies in a trial-and-error learning task . Inman C, ed. PLoS Comput Biol. 2018;14(11):e1006621. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006621

Grote T, Berens P. On the ethics of algorithmic decision-making in healthcare . J Med Ethics . 2020;46(3):205-211. doi:10.1136/medethics-2019-105586

Bigler RS, Clark C. The inherence heuristic: A key theoretical addition to understanding social stereotyping and prejudice. Behav Brain Sci . 2014;37(5):483-4. doi:10.1017/S0140525X1300366X

del Campo C, Pauser S, Steiner E, et al. Decision making styles and the use of heuristics in decision making . J Bus Econ. 2016;86:389–412. doi:10.1007/s11573-016-0811-y

Marewski JN, Gigerenzer G. Heuristic decision making in medicine . Dialogues Clin Neurosci . 2012;14(1):77-89. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.1/jmarewski

Zheng Y, Yang Z, Jin C, Qi Y, Liu X. The influence of emotion on fairness-related decision making: A critical review of theories and evidence . Front Psychol . 2017;8:1592. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01592

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Memberships

Heuristic Method

Heuristic Method: this article explains the concept of the Heuristic Method , developed by George Pólya in a practical way. After reading it, you will understand the basics of this powerful Problem Solving tool.

What is the Heuristic Method?

A heuristic method is an approach to finding a solution to a problem that originates from the ancient Greek word ‘eurisko’, meaning to ‘find’, ‘search’ or ‘discover’. It is about using a practical method that doesn’t necessarily need to be perfect. Heuristic methods speed up the process of reaching a satisfactory solution.

Previous experiences with comparable problems are used that can concern problem situations for people, machines or abstract issues. One of the founders of heuristics is the Hungarian mathematician György (George) Pólya , who published a book about the subject in 1945 called ‘How to Solve It’. He used four principles that form the basis for problem solving.

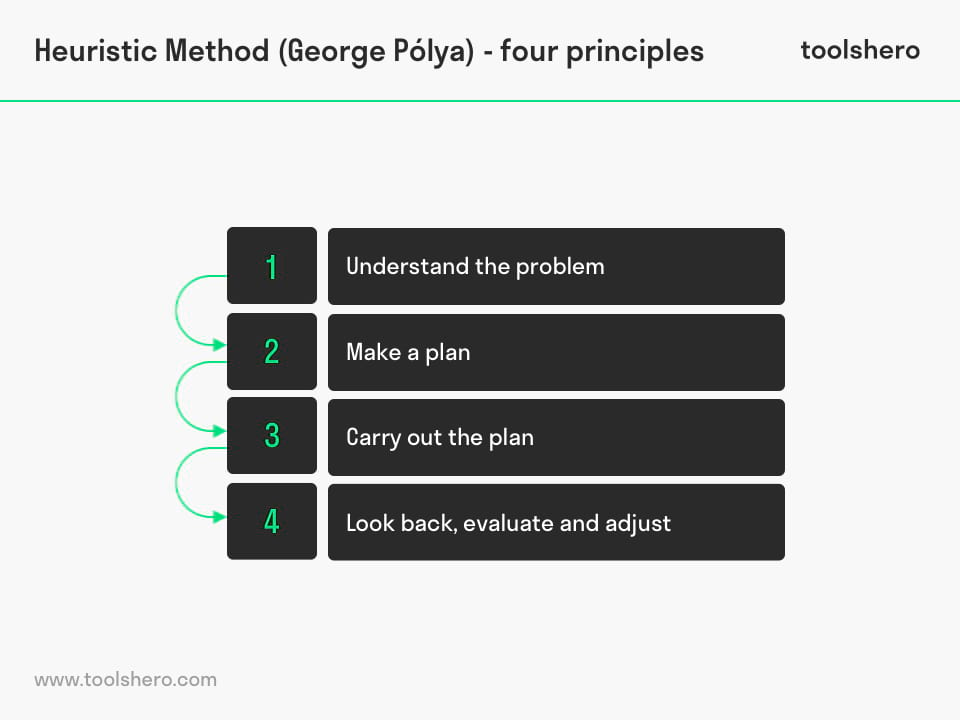

Heuristic method: Four principles

Pólya describes the following four principles in his book:

- try to understand the problem

- make a plan

- carry out this plan

- evaluate and adapt

If this sequence doesn’t lead to the right solution, Pólya advises to first look for a simpler problem.

A solution may potentially be found by first looking at a similar problem that was possible to solve. With this experience, it’s possible to look at the current problem in another way.

First principle of the heuristic method: understand the problem

It’s more difficult than it seems, because it seems obvious. In truth, people are hindered when it comes to finding an initially suitable approach to the problem.

It can help to draw the problem and to look at it from another angle. What is the problem, what is happening, can the problem be explained in other words, is there enough information available, etc. Such questions can help with the first evaluation of a problem issue.

Second principle of the heuristic method: make a plan

There are many ways to solve problems. This section is about choosing the right strategy that best fits the problem at hand. The reversed ‘working backwards’ can help with this; people assume to have a solution and use this as a starting point to work towards the problem.

It can also be useful to make an overview of the possibilities, delete some of them immediately, work with comparisons, or to apply symmetry. Creativity comes into play here and will improve the ability to judge.

Third principle of the heuristic method: carry out the plan

Once a strategy has been chosen, the plan can quickly be implemented. However, it is important to pay attention to time and be patient, because the solution will not simply appear.

If the plan doesn’t go anywhere, the advice is to throw it overboard and find a new way.

Fourth principle of the heuristic method: evaluate and adapt

Take the time to carefully consider and reflect upon the work that’s already been done. The things that are going well should be maintained, those leading to a lesser solution, should be adjusted. Some things simply work, while others simply don’t.

There are many different heuristic methods, which Pólya also used. The most well-known heuristics are found below:

1. Dividing technique

The original problem is divided into smaller sub-problems that can be solved more easily. These sub-problems can be linked to each other and combined, which will eventually lead to the solving of the original problem.

2. Inductive method

This involves a problem that has already been solved, but is smaller than the original problem. Generalisation can be derived from the previously solved problem, which can help in solving the bigger, original problem.

3. Reduction method

Because problems are often larger than assumed and deal with different causes and factors, this method sets limits for the problem in advance. This reduces the leeway of the original problem, making it easier to solve.

4. Constructive method

This is about working on the problem step by step. The smallest solution is seen as a victory and from that point consecutive steps are taken. This way, the best choices keep being made, which will eventually lead to a successful end result.

5. Local search method

This is about the search for the most attainable solution to the problem. This solution is improved along the way. This method ends when improvement is no longer possible.

Exact solutions versus the heuristic method

The heuristic approach is a mathmatical method with which proof of a good solution to a problem is delivered. There is a large number of different problems that could use good solutions. When the processing speed is equally as important as the obtained solution, we speak of a heuristic method.

The Heuristic Method only tries to find a good, but not necessarily optimal, solution. This is what differentiates heuristics from exact solution methods, which are about finding the optimal solution to a problem. However, that’s very time consuming, which is why a heuristic method may prove preferable. This is much quicker and more flexible than an exact method, but does have to satisfy a number of criteria.

It’s Your Turn

What do you think? Is the Heuristic Method applicable in your personal or professional environment? Do you recognize the practical explanation or do you have more suggestions? What are your success factors for solving problems

Share your experience and knowledge in the comments box below.

More information

- Groner, R., Groner, M., & Bischof, W. F. (2014). Methods of heuristics . Routledge .

- Newell, A. (1983). The heuristic of George Polya and its relation to artificial intelligence . Methods of heuristics, 195-243.

- Polya, G. (2014, 1945). How to solve it: A new aspect of mathematical method . Princeton university press .

How to cite this article: Mulder, P. (2018). Heuristic Method . Retrieved [insert date] from ToolsHero: https://www.toolshero.com/problem-solving/heuristic-method/

Add a link to this page on your website: <a href=”https://www.toolshero.com/problem-solving/heuristic-method/”>ToolsHero: Heuristic Method</a>

Published on: 29/05/2018 | Last update: 04/03/2022

Did you find this article interesting?

Your rating is more than welcome or share this article via Social media!

Average rating 4.6 / 5. Vote count: 13

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Patty Mulder

Patty Mulder is an Dutch expert on Management Skills, Personal Effectiveness and Business Communication. She is also a Content writer, Business Coach and Company Trainer and lives in the Netherlands (Europe). Note: all her articles are written in Dutch and we translated her articles to English!

ALSO INTERESTING

PDCA Cycle by Deming: Meaning and Steps

Straw Man Proposal: The basics and template

TRIZ Method of Problem Solving explained

Leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

BOOST YOUR SKILLS

Toolshero supports people worldwide ( 10+ million visitors from 100+ countries ) to empower themselves through an easily accessible and high-quality learning platform for personal and professional development.

By making access to scientific knowledge simple and affordable, self-development becomes attainable for everyone, including you! Join our learning platform and boost your skills with Toolshero.

POPULAR TOPICS

- Change Management

- Marketing Theories

- Problem Solving Theories

- Psychology Theories

ABOUT TOOLSHERO

- Free Toolshero e-book

- Memberships & Pricing

What is Heuristic Thinking? Unraveling the Mind’s Shortcuts

Within the intricate labyrinth of human cognition, our brains shine as adept problem solvers, perpetually seeking efficient paths through life’s complexities.

One such cognitive tool in our mental arsenal is heuristic thinking, a strategy that enables swift decision-making and problem-solving, often leaning on intuition and past experiences.

In this discussion, we’ll embark on a journey into the captivating realm of heuristic thinking, delving into its defining characteristics, merits, limitations, real-world illustrations, and techniques to mitigate potential biases associated with this cognitive approach.

What is Heuristic Thinking?

Heuristic thinking, often colloquially referred to as “rule of thumb” or “common sense” thinking, constitutes a fascinating cognitive process deeply ingrained in human decision-making.

At its core, heuristic thinking is all about navigating the complexities of life and arriving at practical decisions swiftly, even when confronted with limited information or constrained by time.

Unlike exhaustive, analytical approaches that meticulously dissect all available data, heuristic thinking employs mental shortcuts or rules of thumb to streamline decision-making.

Think of it as a mental toolbox brimming with pragmatic shortcuts for problem-solving and judgment formation.

These shortcuts help us cut through the noise of information overload and tackle dilemmas efficiently, especially in situations where time is of the essence.

Characteristics of Heuristic Thinking

Heuristic thinking, with its pragmatic and efficient approach, is guided by several fundamental principles that shape its decision-making processes. Let’s explore these key facets in greater detail:

Simplicity

At the heart of heuristic thinking lies a preference for simplicity over unnecessary complexity.

It thrives on finding straightforward solutions that demand minimal cognitive effort.

In a world often inundated with information and choices, simplicity becomes a valuable ally, allowing us to streamline decision-making and conserve mental resources.

Heuristic thinking operates at an accelerated pace.

It excels in situations that require rapid decision-making, spanning the spectrum from mundane daily choices to high-pressure, time-sensitive emergencies.

The ability to make swift decisions can be invaluable, particularly when faced with urgent matters.

Pattern recognition

One of the central tenets of heuristic thinking is its reliance on pattern recognition.

It draws upon our past experiences and knowledge to recognize recurring patterns and apply familiar solutions to current challenges.

This reliance on patterns from the past aids in quick decision-making by tapping into our reservoir of accumulated wisdom.

Heuristic thinking often places a significant emphasis on intuition and gut feelings.

When confronted with uncertainty or when exhaustive analysis is impractical, relying on one’s intuitive sense becomes a valuable heuristic tool.

This intuitive decision-making process , honed by years of experience, can be surprisingly accurate and efficient.

Pros and Cons of Heuristic Thinking

The advantages of heuristic thinking are multifaceted, with its merits extending to various aspects of decision-making and problem-solving.

Let’s delve deeper into the pros of heuristic thinking:

Efficiency

One of the most prominent advantages of heuristic thinking is its efficiency.

This cognitive approach excels in delivering swift solutions to problems and challenges.

In situations where time is of the essence, such as emergencies or fast-paced environments, the ability to arrive at quick decisions is invaluable.

Resource conservation

Heuristic thinking operates as an effective mental resource manager.

It recognizes that exhaustive analysis isn’t always necessary or practical.

By deploying mental shortcuts and relying on past experiences and intuition, heuristic thinking conserves mental resources.

This conservation is particularly beneficial in situations where cognitive overload is a real concern.

Adaptability

Heuristic thinking showcases remarkable adaptability.

It can seamlessly adapt to a wide array of contexts and scenarios.

Whether it’s making everyday choices, navigating complex problems, or addressing novel challenges, heuristic thinking remains versatile.

This adaptability is a testament to its effectiveness in diverse situations.

Problem-solving

Problem-solving finds an exceptional ally in heuristic thinking.

It serves as a potent instrument for resolving challenges by drawing upon our wealth of past experiences and knowledge.

This enables us to discern patterns and employ tried-and-true solutions when faced with novel predicaments.

This adeptness in problem-solving significantly bolsters our capacity to address intricate issues with a blend of pragmatism and assurance.

Decisiveness

The efficiency of heuristic thinking contributes to decisiveness.

It enables individuals to make choices with conviction, even when faced with uncertainty. This decisiveness can be a valuable trait in both personal and professional spheres.

While heuristic thinking offers notable advantages, it also comes with its share of limitations and potential drawbacks. Let’s explore some of the cons associated with heuristic thinking:

One of the most significant concerns tied to heuristic thinking is its susceptibility to cognitive biases.

Heuristics rely on mental shortcuts, often drawing from past experiences and stereotypes.

These shortcuts can inadvertently lead to biases, influencing judgments and decisions based on preconceived notions rather than objective assessment.

Such biases can introduce errors and distortions into decision-making processes.

Inaccuracy

Heuristic thinking may not always yield the most accurate decisions, particularly when confronted with complex or multifaceted problems.

While it excels in delivering quick solutions, these solutions may lack the depth and precision required for intricate challenges.

In situations where accuracy is paramount, relying solely on heuristics can prove inadequate.

Overreliance on heuristics can lead to rigidity in thinking.

When individuals become too reliant on familiar mental shortcuts, they may struggle to adapt when faced with novel or unique situations.

This rigidity can hinder creativity and problem-solving in scenarios that demand fresh perspectives and innovative approaches .

Limited scope

Heuristic thinking is most effective when applied to specific types of problems and decisions.

It may not be suitable for all situations, particularly those that require exhaustive analysis, critical thinking, or deep exploration of alternatives.

Its effectiveness is context-dependent, and it’s important to recognize when it may not be the most appropriate approach.

Risk of Error

While heuristic thinking can yield efficient decisions, it carries an inherent risk of error.

Quick judgments based on heuristics may not always align with the best course of action, and individuals employing this approach must be mindful of the potential for mistakes.

Examples of Heuristic Thinking

These heuristics, while often helpful, can sometimes lead to cognitive biases and errors in judgment. Let’s explore a few notable cognitive heuristics:

Availability heuristic

This heuristic involves people overestimating the probability of events based on how easily those events come to mind.

When something is particularly vivid or receives extensive media coverage, it becomes more accessible in our minds, leading us to perceive it as more likely than it might be.

For example, after a high-profile plane crash, individuals may perceive air travel as riskier than statistically supported due to the vividness of media coverage.

Representativeness heuristic

This cognitive shortcut involves judging the likelihood of an event based on how closely it resembles a prototype or a stereotypical image.

People tend to make judgments about individuals or events based on how similar they appear to a preconceived notion.

For instance, assuming someone is a skilled chef solely based on their appearance, such as wearing a chef’s hat, without considering any concrete evidence of their culinary abilities.

Anchoring heuristic

In this heuristic, individuals anchor their judgments to a reference point, often the first piece of information encountered.

The initial information acts as a mental anchor that influences subsequent judgments or decisions.

For example, in a negotiation, the first offer made can significantly shape the final outcome.

If the initial offer is high, subsequent offers and counteroffers tend to revolve around that anchor.

Overcoming Biases Associated with Heuristic Thinking

To mitigate the potential pitfalls associated with cognitive heuristics, individuals can employ various strategies and approaches:

A fundamental step is recognizing your reliance on heuristics.

Be mindful of when and how you might be using mental shortcuts in your decision-making process.

Awareness allows you to pause and consider whether a heuristic is applicable in a given situation or if a more thorough analysis is warranted.

Critical thinking

Engage in critical thinking by actively evaluating your judgments and decisions.

Challenge your assumptions and seek additional information or evidence before finalizing a conclusion.

Critical thinking encourages a deeper exploration of the factors at play, helping to counteract the effects of heuristics.

Diverse perspectives

Broaden your perspective by considering different viewpoints and seeking input from others.

Collaboration and diverse perspectives can act as a counterbalance to biases introduced by heuristics.

When multiple voices contribute to a decision-making process, it can lead to more well-rounded and informed outcomes.

Evidence-based decision-making

Base your decisions on concrete evidence whenever possible.

Rather than relying solely on mental shortcuts or intuitive judgments, strive to gather and analyze relevant data and information.

Evidence-based decision-making provides a solid foundation for sound judgments.

Reflect and learn

After making decisions, take the time to reflect on their outcomes.

Assess whether your reliance on heuristics had positive or negative effects and what you can learn from the experience.

This reflective process can help you refine your decision-making skills over time.

Heuristic thinking, with its cognitive shortcuts and intuitive decision-making, is a fascinating aspect of human cognition.

While it offers efficiency and adaptability, it also carries the risk of biases.

By understanding its characteristics, recognizing its presence in everyday decisions, and employing strategies to overcome biases, we can harness the power of heuristic thinking while making more informed choices.

As we navigate the intricate labyrinth of our minds, let us appreciate the role of heuristics in simplifying our complex world.

Unveiling the Mysteries of Gleipnir Norse Mythology

Navigating Love with Avoidant Personality Disorder in Relationships

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Forgot password?

Enter your account data and we will send you a link to reset your password.

Your password reset link appears to be invalid or expired.

Privacy policy.

To use social login you have to agree with the storage and handling of your data by this website. %privacy_policy%

Add to Collection

Public collection title

Private collection title

No Collections

Here you'll find all collections you've created before.

Hey Friend! Before You Go…

Get the best viral stories straight into your inbox before everyone else!

Email address:

Don't worry, we don't spam

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

A heuristic is a mental shortcut that allows an individual to make a decision, pass judgment, or solve a problem quickly and with minimal mental effort. While heuristics can reduce the burden of decision-making and free up limited cognitive resources, they can also be costly when they lead individuals to miss critical information or act on unjust biases.

- Understanding Heuristics

- Different Heuristics

- Problems with Heuristics

As humans move throughout the world, they must process large amounts of information and make many choices with limited amounts of time. When information is missing, or an immediate decision is necessary, heuristics act as “rules of thumb” that guide behavior down the most efficient pathway.

Heuristics are not unique to humans; animals use heuristics that, though less complex, also serve to simplify decision-making and reduce cognitive load.

Generally, yes. Navigating day-to-day life requires everyone to make countless small decisions within a limited timeframe. Heuristics can help individuals save time and mental energy, freeing up cognitive resources for more complex planning and problem-solving endeavors.

The human brain and all its processes—including heuristics— developed over millions of years of evolution . Since mental shortcuts save both cognitive energy and time, they likely provided an advantage to those who relied on them.

Heuristics that were helpful to early humans may not be universally beneficial today . The familiarity heuristic, for example—in which the familiar is preferred over the unknown—could steer early humans toward foods or people that were safe, but may trigger anxiety or unfair biases in modern times.

The study of heuristics was developed by renowned psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. Starting in the 1970s, Kahneman and Tversky identified several different kinds of heuristics, most notably the availability heuristic and the anchoring heuristic.

Since then, researchers have continued their work and identified many different kinds of heuristics, including:

Familiarity heuristic

Fundamental attribution error

Representativeness heuristic

Satisficing

The anchoring heuristic, or anchoring bias , occurs when someone relies more heavily on the first piece of information learned when making a choice, even if it's not the most relevant. In such cases, anchoring is likely to steer individuals wrong .

The availability heuristic describes the mental shortcut in which someone estimates whether something is likely to occur based on how readily examples come to mind . People tend to overestimate the probability of plane crashes, homicides, and shark attacks, for instance, because examples of such events are easily remembered.

People who make use of the representativeness heuristic categorize objects (or other people) based on how similar they are to known entities —assuming someone described as "quiet" is more likely to be a librarian than a politician, for instance.

Satisficing is a decision-making strategy in which the first option that satisfies certain criteria is selected , even if other, better options may exist.

Heuristics, while useful, are imperfect; if relied on too heavily, they can result in incorrect judgments or cognitive biases. Some are more likely to steer people wrong than others.

Assuming, for example, that child abductions are common because they’re frequently reported on the news—an example of the availability heuristic—may trigger unnecessary fear or overprotective parenting practices. Understanding commonly unhelpful heuristics, and identifying situations where they could affect behavior, may help individuals avoid such mental pitfalls.

Sometimes called the attribution effect or correspondence bias, the term describes a tendency to attribute others’ behavior primarily to internal factors—like personality or character— while attributing one’s own behavior more to external or situational factors .

If one person steps on the foot of another in a crowded elevator, the victim may attribute it to carelessness. If, on the other hand, they themselves step on another’s foot, they may be more likely to attribute the mistake to being jostled by someone else .

Listen to your gut, but don’t rely on it . Think through major problems methodically—by making a list of pros and cons, for instance, or consulting with people you trust. Make extra time to think through tasks where snap decisions could cause significant problems, such as catching an important flight.

Many apps claim to use nudges but instead use simple reminders that are just re-labeled as nudges. The terminology matters—true nudges use more potent behavioral science.

When you make a mistake for the third time, it's probably about you, not the situation.

The myth of the perfect question, the "fit" fallacy, and more.

Your plans should not be set based on the wisdom shared by successful people. They should be based on your context, your strengths, and your creative inspiration from that wisdom.

Discover how the anchoring effect, a subtle cognitive bias, shapes our decisions across life's domains.

Discrimination is how we treat groups of people. Bias is how we think about them. Can better understanding cognitive biases make a difference in the fight against discrimination?

Artificial intelligence already plays a role in deciding who’s getting hired. The way to improve AI is very similar to how we fight human biases.

Think you are avoiding the motherhood penalty by not having children? Think again. Simply being a woman of childbearing age can trigger discrimination.

Psychological experiments on human judgment under uncertainty showed that people often stray from presumptions about rational economic agents.

Are experts more confident in what they know than what they don't? Yes, but it's not so clear-cut.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

When we fall prey to perfectionism, we think we’re honorably aspiring to be our very best, but often we’re really just setting ourselves up for failure, as perfection is impossible and its pursuit inevitably backfires.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience