This site uses various technologies, as described in our Privacy Policy, for personalization, measuring website use/performance, and targeted advertising, which may include storing and sharing information about your site visit with third parties. By continuing to use this website you consent to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

Enter your email to unlock an extra $25 off an sat or act program, by submitting my email address. i certify that i am 13 years of age or older, agree to recieve marketing email messages from the princeton review, and agree to terms of use., guide to the ap world history exam.

The AP ® World History: Modern exam covers historical developments from c 1200 to the present. It will test topics and skills discussed in your Advanced Placement World History: Modern course. If you score high enough, your AP score could earn you college credit !

Check out our AP World History Guide for what you need to know about the exam:

- AP World History: Modern Exam Overview

- AP World History: Modern Question Types

- AP World History: Modern Scoring

- How to Prepare

AP World History Exam Overview

The AP World History: Modern exam takes 3 hours and 15 minutes to complete and is composed of: a multiple-choice, short answer, and free response section.

AP World History Question Types

Multiple-choice.

AP World History: Modern multiple-choice questions are grouped into sets of usually 3-4 questions. They are based on primary or secondary sources, including excerpts from historical documents or writings, images, graphs, and maps. This section will test your ability to analyze and engage with the source materials while recalling what you already know about world history.

Short Answer

The AP World History: Modern short answer questions require you to respond to a secondary source for Question 1 and a primary source for Question 2, both focusing on historical developments between 1200 and 2001. Students will choose between two options (Questions 3 or 4) for the final required short-answer question, each one focusing on a different time periods of 1200 to 1750 and 1750 to 2001.

For all short answer questions, you’ll be asked to:

- Analyze the provided sources

- Analyze historical developments and processes described in the sources

- Put those historical developments and processes in context

- Make connections between those historical developments and processes

Document-Based Question (DBQ)

The AP World History: Modern DBQ presents a prompt and seven historical documents that are intended to show the complexity of a particular historical issue between the years 1450 and 2001. You will need to develop an argument that responds to the prompt and support that argument with evidence from both the documents and your own knowledge of world history. To earn the best score, you should incorporate outside knowledge and be able to relate the issues discussed in the documents to a larger theme, issue, or time period.

Long Essay Question

The AP World History: Modern Long Essay Question presents three questions and you have to choose one to answer. All questions will test the same skills but will focus on different historical periods (i.e., from c. 1200–1750, from c. 1450–1900, or from c. 1750–2001). Similar to the DBQ, you will need to develop and support an answer to the question you picked based on historical evidence to earn the best score possible.

For a comprehensive content review, check out our book, AP World History Prep

AP World History Review

The College Board is very detailed in what they require your AP teacher to cover in his or her AP World History course. They explain that you should be familiar with world history events from the following nine units that fall within four major time periods from 1200 to the present.

Read More: Review for the exam with our AP World History Cram Courses

AP scores are reported from 1 to 5. Here’s how students scored on AP World History exam in May 2020:

Source: College Board

How can I prepare?

AP classes are great, but for many students they’re not enough! For a thorough review of AP World History: Modern content and strategy, pick the AP prep option that works best for your goals and learning style. You can also check out our AP World History: Modern test prep book here .

- AP Exams

Explore Colleges For You

Connect with our featured colleges to find schools that both match your interests and are looking for students like you.

Career Quiz

Take our short quiz to learn which is the right career for you.

Get Started on Athletic Scholarships & Recruiting!

Join athletes who were discovered, recruited & often received scholarships after connecting with NCSA's 42,000 strong network of coaches.

Best 390 Colleges

168,000 students rate everything from their professors to their campus social scene.

SAT Prep Courses

1400+ course, act prep courses, free sat practice test & events, 1-800-2review, free digital sat prep try our self-paced plus program - for free, get a 14 day trial.

Enrollment Advisor

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 1

1-877-LEARN-30

Mon-Fri 9AM-10PM ET

Sat-Sun 9AM-8PM ET

Student Support

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 2

Mon-Fri 9AM-9PM ET

Sat-Sun 8:30AM-5PM ET

Partnerships

- Teach or Tutor for Us

College Readiness

International

Advertising

Affiliate/Other

- Enrollment Terms & Conditions

- Accessibility

- Cigna Medical Transparency in Coverage

Register Book

Local Offices: Mon-Fri 9AM-6PM

- SAT Subject Tests

Academic Subjects

- Social Studies

Find the Right College

- College Rankings

- College Advice

- Applying to College

- Financial Aid

School & District Partnerships

- Professional Development

- Advice Articles

- Private Tutoring

- Mobile Apps

- International Offices

- Work for Us

- Affiliate Program

- Partner with Us

- Advertise with Us

- International Partnerships

- Our Guarantees

- Accessibility – Canada

Privacy Policy | CA Privacy Notice | Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information | Your Opt-Out Rights | Terms of Use | Site Map

©2024 TPR Education IP Holdings, LLC. All Rights Reserved. The Princeton Review is not affiliated with Princeton University

TPR Education, LLC (doing business as “The Princeton Review”) is controlled by Primavera Holdings Limited, a firm owned by Chinese nationals with a principal place of business in Hong Kong, China.

Question Types on the AP World History: Modern Exam

April 9, 2024.

The AP World History: Modern exam is a 3-hour and 15-minute exam that tests your ability to think like a historian. It will ask you to analyze primary and secondary sources and identify patterns and connections that can support a historical interpretation. This AP exam will also test your knowledge of historical concepts covered in the AP World History: Modern course. Before taking the exam, review the types of questions you’ll encounter so you get comfortable with the format and know how to manage your time. Practice answering sample questions, like the ones below, and understand how the exam is graded, especially the free-response questions, to maximize your exam score. In this guide, we break down what you need to know about the four question types on the AP World History: Modern exam.

What are the Four Question Types on the AP World History: Modern Exam?

There are four types of questions on the AP World History: Modern exam, including multiple-choice questions, short-answer questions, and free-response (essay) questions. The free-response questions are composed of a document-based question (DBQ) and a long essay question (LEQ). In the first half of the exam, you will have 55 minutes to complete 55 multiple-choice questions. Immediately following, you’ll answer three short-answer questions in 40 minutes. The second half exam gives you 100 minutes to answer both the DBQ and LEQ.

Multiple-Choice Questions on the AP World History: Modern Exam

The first part of the AP exam requires you to answer 55 multiple-choice questions in 55 minutes. This section of the exam is worth 40% of your total exam grade.

Each multiple-choice question on the AP World History: Modern exam includes four answer options; you will pick the one that BEST answers the question. These questions will be grouped in approximately fifteen to twenty clusters, typically of three or four questions. One point is awarded for each correct answer. Incorrect answers are not penalized, so answering all the multiple-choice questions is important even if you have to guess.

Expert tip: Start by eliminating incorrect answers. Every distractor, or wrong answer, is supposed to sound somewhat plausible. Still, a quick but careful reading generally allows you to eliminate at least one wrong answer if not two. This is the first thing you should do. If you can quickly pick the correct answer from the two or three that remain, do so. If you can’t, flag the question and return to it during your second run through the exam.

[ LISTEN: Barron’s AP World History: Modern Podcast Episode 9: “Multiple-Choice Questions” on Apple and Spotify ]

Sample Multiple-Choice Question

The following is a sample multiple-choice question similar to one you might find on the AP World History: Modern exam. In this example, you must read the following excerpts and use them to answer the question below.

The story of my great-grandmother was typical of millions of Chinese women [before the 1911 revolution]. She came from a family of tanners. Because her family was not intellectual and did not hold any official post, and because she was a girl, she was not given a name. Being the second daughter, she was simply called “Number Two Girl.” [She never met her husband] before her wedding. In fact, falling in love was considered shameful, a family disgrace. Not because it was taboo, but because young people were not supposed to be exposed to situations where such a thing could happen, partly because it was immoral for them to meet, and partly because marriage was seen above all as a duty, an arrangement between two families. With luck, one could fall in love after getting married.

from Jung Chang, Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China (1991)

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife. This truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding families, that he is considered as the rightful property of some one or other of their daughters.

from Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice (1813)

- The observations made in the above quotations are best understood in the context of which of the following? a. The use of religious doctrine to regulate the role of women in society b. The impact of industrialization on family structures c. The oppression of women due to the rise of social Darwinist ideologies d. The shaping of marriage customs by prevailing social and economic norms

Check your answer.

Answer: (D) Contextualization and process of elimination help to answer this question. Neither quotation speaks directly to religion or industrialization, making A and B unlikely. While oppression is evident in the first quotation, it is not overtly so in the second, and has nothing to do with social Darwinism in any case, so C is incorrect. In both cases, but in different ways, the impact of social and economic factors on marriage is at stake, and those are what tie the questions together.

Short-Answer Questions on the AP World History: Modern Exam

After finishing the multiple-choice section, you’ll answer three short-answer questions. You will have 40 minutes to complete this section of the test, giving you roughly 13 minutes to answer each question. This section is worth 20% of your total exam grade.

The short-answer questions will ask you to use content knowledge and various historical skills to provide written responses to three short-answer questions. You must complete the first and second questions; you will then have the choice to complete the third or fourth.

- Short-answer questions #1 and #2: These questions can cover any time period between 1200 and the present. The first question will require you to assess some sort of secondary source, and the second will test you on primary source material.

- Short-answer questions #3 and #4: These questions will not provide any specific stimulus material. The third question will cover the period from 1200 to 1750, and the fourth will focus on the years between 1750 and the present.

Each short-answer question will ask you to do three things, each of which will be worth one point. You are not required to develop a thesis for the short-answer questions. Your main strategy should be to complete all three questions within the set amount of time and to clearly indicate that, in each case, you have satisfactorily accomplished all three goals. Lengthy answers are unnecessary — one long paragraph, or perhaps two or three short paragraphs, should suffice.

[ LISTEN: Barron’s AP World History: Modern Podcast Episode 10: “Short-Answer Questions” on Apple and Spotify ]

Sample Short-Answer Question

Below is an example of a short-answer question similar to one you will encounter on the AP World History: Modern exam. Use the two passages below to answer all parts of the question that follows.

It is nowadays common for Indian history textbooks to treat the various “empires” that successively occupied the stage of Indian history as so many successive repetitions with merely different names for offices and institutions that in substance remained the same: namely, the King, the Ministers, the Provinces, the Governors, and so on. But D.D. Kosambi, in his Introduction to the Study of Indian History, rightly observed that this repetitive succession cannot be assumed, and that each regime, when subjected to critical study, displays distinct elements. We know most, of course, about the Mughal Empire, which displays so many striking features. In its large extent and long duration, it had only one precedent, in the Mauryan Empire, some 1,900 years earlier. Some scholars regard it as the fulfillment of the political ambitions embodied in Indian polity for three millennia. And yet there is also a temptation to see in the Mughal Empire a primitive version of the modern state. Its existence belongs to a period when the dawn of modern technology had occurred in Europe, and some of the rays of that dawn had also fallen on Asia. Can it then be said that the foundations of the Mughal Empire lay in artillery, the most brilliant and dreadful representative of modern technology, as much as did those of the modern absolute monarchies of Europe?

M. Athar Ali, “Towards an Interpretation of the Mughal Empire,” 1978

The prevailing view of the Mughal Empire has been based on the mistaken assumption that this state was a kind of unfinished, unfocused prototype of the British Indian Empire of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A more fruitful approach is to treat the Mughal Empire as one example of the [older-fashioned] patrimonial-bureaucratic empire, featuring a depiction of the emperor as a divinely-aided patriarch, the household as the central element in government, members of the army as dependent on the emper – or, the administration as a loosely structured group of men controlled by the imperial household. It seems clear that to accept this interpretation of the empire is to accept the necessity of re-examining the entire structure of Mughal political activity.

Stephen P. Blake, “The Patrimonial-Bureaucratic Empire of the Mughals,” 1979

- Using the excerpts above, answer (a), (b), and (c). a. Provide ONE piece of historical evidence (not specifically mentioned in the passage) that would support Ali’s interpretation of the Mughal Empire’s fundamental nature. b. Provide ONE piece of historical evidence (not specifically mentioned in the passage) that would support Blake’s interpretation of the Mughal Empire’s fundamental nature. c. Explain ONE way in which the views about Mughal governance expressed in the two passages led the authors to propose different interpretations of the empire’s fundamental nature.

Possible answers:

The scholarly debate at stake here is whether the Mughal Empire is best seen as the product of early political modernization—and a departure from earlier regimes ruling India—or as a government that followed older patterns of rulership. Ali promotes the first argument, while Blake, using the label “patrimonial” (in which the state is considered the personal property of a monarchical ruler), takes the second position. The easiest way to answer Part A is to mention the Mughal Empire’s success as a “gunpowder empire,” along with Ottoman Turkey, an adoption of modern technology that buttresses Ali’s thesis. One could also discuss the empire’s elaborate bureaucracy, much of which was in fact kept in place by the British as they extended their colonial reach over India. In favor of Blake’s argument in Part B, one could easily mention how religious policy—especially pertaining to Muslim rulership over India’s Hindu majority—varied widely based on the personal preferences of any given emperor, from Akbar’s remarkable tolerance to Aurangzeb’s extreme Islamic rigidity.

In explaining the differences between the two views, as Part C requires, it might be tempting to point to the two authors’ national differences, one being Indian, the other not. However, the debate does not seem to revolve around this question. Even though one might be able to say that patriotism inclines Ali to favor an argument depicting Mughal India as more modern than Blake appears to think, highlighting this sort of difference in this case runs the risk of stereotyping national viewpoints. (Still, be aware that national perspectives will sometimes affect debates of this type, especially when it comes to Western imperial treatment of other parts of the world, so in some instances it could be worth bringing up.) Perhaps the best way to answer this part of the question would be to point out that Ali seems mostly concerned with the Mughal Empire’s place as a particular stage in India’s long history, while Blake is mainly interested in the Mughal Empire as a political system typical of its era and in comparison with other regimes in Eurasia during a particular time.

Free-Response (Essay) Questions on the AP World History: Modern Exam

The free-response section of the AP World History: Modern exam lasts 100 minutes and consists of the document-based question (DBQ) and the long essay question (LEQ). The section begins with a 15-minute reading period, during which you are allowed to read both questions, examine the DBQ documents, and plan your responses (taking notes and making outlines). Alternatively, you can start writing immediately. Either way, you can write the essays in whichever order you wish, and you can use the time however you please. We suggest using the 15-minute reading period to read the documents and outline your answers. The rest of the time should be divided more or less evenly, with perhaps 45 minutes spent on the DBQ and 40 minutes on the LEQ.

A commonly followed guideline is to write the DBQ first. The documents will be fresh in your mind, and because the DBQ operates according to the most complicated rules, it will be good to have it out of the way. Just make sure to leave enough time for the LEQ! Practice writing essays in 40 minutes or less to improve your time management skills for this section.

The Document-Based Question on the AP World History: Modern Exam

Unlike the other essays, the DBQ on the AP World History: Modern exam asks you to perform well on two fronts. Not only does the essay itself have to be well written (complete with a good thesis), but you must demonstrate skillful handling of the seven documents. The DBQ is worth 25% of your total exam score.

The DBQ will focus on some time period between 1450 and the present. When taken together, the documents address a particular theme or issue, typically with a fairly narrow focus when it comes to era, geography, and topic. For example, a DBQ might ask about industrialization in nineteenth-century Asia or European imperialism in a specific part of the world. Or it might ask about a noteworthy cultural trend, technological innovation, trade network, or sociological development.

A DBQ will tie your use of the documents to one of several historical reasoning skills. You may be told to compare and contrast two things, to trace continuity and change over time, or to analyze causes and consequences. You will organize the documents into groups (typically three of them) and discuss the documents’ context as well as their creators’ point of view or purpose. To test your understanding of how documents can sometimes be of limited usefulness, the DBQ will ask you to identify additional evidence that, if provided, would shed further light on the question.

Expert Tip: Vague language equals a weak thesis! Be as specific as possible—but without getting swamped. Your thesis shouldn’t be too long or contain too much detail.

[ LISTEN : Barron’s AP World History: Modern Podcast Episode 11: “The Document-Based Question” on Apple and Spotify ]

Sample Document-Based Question

Use Documents 1–7 to answer the following sample document-based question.

- Evaluate the extent to which Pan-Arabism and Pan-Africanism have differed in their nature and political effectiveness in the modern era.

During the global wave of decolonization that followed the end of World War II, two political ideologies seemed poised to gain permanent prominence: Pan-Africanism and Pan-Arabism. Both movements followed the same logic, attempting to empower previously colonized peoples by encouraging a sense of unity based on broad cultural and ethnic identities, rather than on narrow national ones. A key difference, however, is that Pan-Africanism defined itself mainly in terms of opposition to racial and colonial oppression, whereas Pan-Arabism was in a better position to appeal to a common linguistic and religious heritage. In the end, while both achieved certain successes, both proved weaker than the lure of traditional nationalism and fell far short of their original aspirations.

Pan-Africanism had deeper roots than Pan-Arabism, and much of it sprang from the discontent felt by African-descended populations who lived among abusive white majorities or under white colonial rule. These experiences are spoken of by the 1920 “Declaration of the Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World” (document 4) and the 1945 poem “In Memoriam,” by Leopold Senghor (document 7). Senghor, from the French colony of Senegal, describes the alienation he feels living in Paris, surrounded by French whites—supposedly his “brothers,” but completely different, and to be feared, with their “faces of stone,” “blue eyes,” and “hard hands.” The contrast between his native landscape and holidays with the streets of Paris and the Catholic Day of All Saints reminds him that he does not belong. As a central figure in the negritude movement, Senghor stressed African identity as a source of strength for all those of African descent living under white rule, no matter where or under which colonial authority. The same viewpoint was expressed even more forcefully by the delegates to the 1920 Convention of the Universal Negro Improvement Association in New York City. The idea here was that all those of African descent shared a common problem— white oppression, whether in the United States, the Caribbean, Europe, or Africa itself under colonial rule—and a common heritage, and should therefore band together, regardless of language or specific tribal origin. The Convention’s “Declaration” went so far as to nominate an actual president of Africa, and to designate a song about Ethiopia as its anthem.

Document 2, an essay from the 1960s by Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere, carries the Pan-African vision into the post-World War II era, when many African nations overthrew colonial regimes or were in the process of doing so. Along with Kwame Nkrumah, who won freedom for Ghana from British rule, Nyerere was one of this time period’s most outspoken supporters of Pan-Africanism. (Also like Nkrumah, Nyerere can be viewed in the larger context of “Third World” political leaders such as Sukarno of Indonesia, Nehru of India, and Nasser of Egypt, all of whom sought ways to strengthen their newly liberated countries and keep them free of Western political interference and economic domination.) Nyerere identifies a key “dilemma” of Pan-Africanism: the fact that African independence has to be achieved country by country, after which it is tempting for each country to focus narrowly on its own interests. He argues vehemently that Africa can prosper only if such temptations are overcome in favor of a larger, more cooperative understanding of what it means to be African. The mural pictured in document 5 is a visual representation of this utopian ideal, which seeks to unite a billion people under one inclusive label, bridging all other ethnic or linguistic differences. Neither document, however, sufficiently addresses the huge difficulties involved with uniting peoples as diverse as those in Africa actually are. While politicians like Nyerere and Nkrumah managed to establish transnational organizations like the Organization of African Unity (now the African Union), conflict and disunity have tended to greatly outweigh Pan-African unity in the decades since World War II. Differences in language, ethnic and tribal identity, and local culture and religion seem to have proven stronger than abstract ideology.

Documents 1, 6, and 3 all have to do with Pan-Arabism. Gamal Nasser, who had just risen to power in Egypt as a nationalist leader, and would outrage much of the West by establishing Egyptian control over the Suez Canal, ranks with Nyerere as a major political figure in the “Third World” during the 1950s and 1960s. Like the Pan-Africanists, Nasser saw Pan-Arabism as a means to build strength and defy the militarily stronger and more economically prosperous nations of the West. To that end, he even managed to join Egypt to Syria and Iraq in a short-lived United Arab Republic. Much more so than Pan-Africanism, Pan-Arabism had the potential to foster transnational unity, because most people in the so-called Arab world shared a common language (Arabic), a common history and cultural heritage, and, in most cases, a common religion (Islam). Document 6, a recent newspaper editorial, makes this exact point in calling for a revival of the Pan-Arab ideal in order to preserve Arab identity in the face of westernization. However, the fact that document 6 has to call for Pan-Arabism in 2012 clearly indicates that, even with the advantage of a common tongue and heritage, Pan-Arabism—like Pan-Africanism—yielded few concrete political results. Some of the region’s smallest nations may have fused together as the United Arab Emirates, but this is hardly a political powerhouse. Document 3, a graphic showing the “Arab world,” with each nation linked to its individual flag, does not say anything overtly—but by its very nature speaks to the failure of Pan-Arabism to overcome national differences in favor of a larger regional identity. Like Nkrumah and Nyerere, Nasser failed to cement in place a larger dream of union.

As rich as the current selection of documents is, you should include additional perspectives to shed even more light on this comparison between Pan-Africanism and Pan-Arabism. While political elites are well represented, the point of view of nonstate actors is not, and there is much historical evidence to show that the concerns of most ordinary people tend to be local or national, and rarely transnational. Even political leaders who theoretically supported Pan-Arabism, like Gaddafi in Libya and Nasser himself, cared more for their own nations’ interest in the end. With respect to Africa, numerous episodes—such as the Biafra War (in which the Igbo minority tried to secede from Nigeria in the late 1960s) and the 1994 genocide committed in Rwanda by the Hutu against their Tutsi neighbors—provide evidence of the real-life difficulties involved with realizing the dream of Pan-African unity. Finally, to contextualize this topic even further, it would be useful to compare it with trends in Asia during this period. There, too, especially in South and Southeast Asia, many nations decolonized, and a number of them tried to form transnational coalitions or alliances. While Pan-Asianism was not attempted to the same degree that Pan-Arabism and Pan-Africanism were, organizations such as the Southeast Asian Treaty Organization (SEATO) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) emerged to accomplish at least some of the same things that Pan-Africanists and Pan-Arabists hoped to bring about in their own regions.

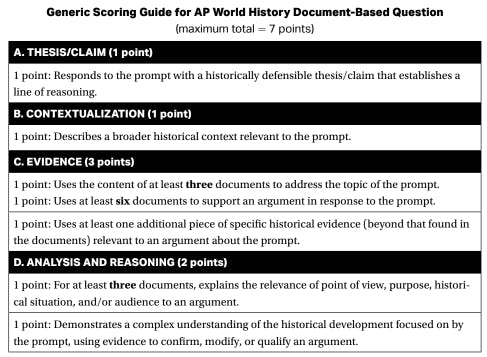

How is the Document-Based Question Scored?

The table below shows the official AP scoring guide for the DBQ. The maximum score you can receive is a “7.”

The Long Essay Question on the AP World History: Modern Exam

The AP World History: Modern exam’s long essay question (LEQ) asks you to develop and support an argument based on evidence. Although you can write this essay before the DBQ if you wish, we recommend you save it for last because of the DBQ’s complexity. Aim to spend about 40 minutes on the LEQ.

You’ll choose between three LEQs. Be sure to select the one you feel the most confident in answering. All three options will test the same historical reasoning skill and focus on the same course theme but cover a different time period: the first will cover 1200–1750, the second will focus on 1450–1800, and the third will do the same for 1750 to the present. The reasoning skill will vary from year to year, rotating through causation, comparison, and continuity/change over time.

[ LISTEN: Barron’s AP World History: Modern Podcast Episode 12: “The Long Essay” on Apple and Spotify ]

Sample Long Essay Prompt

Below are three sets of questions, each reflecting how the AP exam, in any given year, might target a particular historical reasoning skill and course theme. One sample answer—responding to one of the comparison questions—is provided.

Directions: Answer Question 1 or Question 2 or Question 3.

Possible Comparison Questions (Course Theme = State Building)

- In the period 1200 to 1500, states in Europe and in India used various techniques of conquest and rulership to consolidate and centralize their authority. Develop an argument that evaluates the extent to which states in each region succeeded in their goals of political consolidation and centralization.

- In the period 1450 to 1800, the Ottoman Empire and China employed various strategies to legitimate their political authority. Develop an argument that evaluates the extent to which each state succeeded in this goal.

- In the period after 1900, both Latin America and the Middle East significantly modernized their political systems. Develop an argument that evaluates the extent to which this process was accomplished in each region.

Check your answer to Question #3.

The first half of the twentieth century brought immense changes to many parts of the globe. Among these was increased modernization in a number of non-Western regions, including Latin America and the Middle East. Both places faced similar obstacles, such as relative socioeconomic backwardness, heavy influence from outside powers, and limited success in the past with representative government. There were, however, key differences as well. Latin American states, with their generally longer history of independence, tended to be more modern already. Traditional religion was less of a barrier to change in Latin America than in the Middle East, and events like the world wars and the Great Depression affected both areas differently. On the whole, these differences outweighed the similarities, causing Latin America to make more progress toward modernization than the Middle East.

At the beginning of this period, both Latin America and the Middle East suffered from social and economic underdevelopment. Wealthy elites, whether colonial, corporate, or royal and aristocratic, benefited from the unbalanced exploitation of a handful of commodities. In Latin America, these included foodstuffs (beef, coffee, bananas, and other fruit) and natural resources such as copper, steel, fertilizer, and, in some countries, oil. Oil was even more central to the economies of the Middle East, just as it is today. This “banana republic” overexploitation of resources discouraged the healthy diversification of economies and kept societies rigidly stratified, with small upper classes dominating large, impoverished majorities. Although some of this changed between 1900 and 1945, it limited modernization throughout the period.

Another similarity is that Latin American and Middle Eastern states tended to be heavily influenced by outside powers, both before and during this half century. Prior to World War I, much of the Middle East was ruled by the Ottoman Empire or fell into European spheres of influence—and even though the Ottomans fell after WWI, European spheres of influence grew even larger when the post-WWI mandate system placed much of the Middle East, especially the Ottomans’ former Arab possessions, under French and British custody. Most Latin American states had been free since the wars of independence of the early 1800s, but foreign investors (like America’s United Fruit Company) wielded much power over Latin American governments, and the U.S. government regarded the region as part of its political sphere of influence. The Pan- American Union and even Franklin Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy were instruments of U.S. diplomatic interests throughout Latin America. Even when these outside interests did not deliberately oppose modernization (and they often did), it was rarely in their interest to actively support economic diversification, and because dealing with cooperative elite classes was easier than negotiating with elected governments representing a range of popular interests, they did not necessarily support democracy either.

On the other hand, important differences moved Latin America further down the path toward modernization. To begin with, Latin American states, while nonindustrialized by the standards of Western Europe and North America, had undergone more industrialization than most parts of the Middle East. With this kind of foundation to build on, countries like Mexico and Argentina, for example, found it easier to create sizable industrial sectors after WWI. Latin American states also had a tradition of constitutional rule stretching back to the era of Simo'n Bol var in the early 1800s, and while those constitutions were not always perfectly followed, they created a more favorable climate for progress when it came to gender equity, enlarging the middle classes, and reforming electoral systems. Less of this was possible in the Middle East.

Another crucial difference involves the role of religion. Although Catholicism was overwhelmingly central to Latin American culture, and although it tended to exert a conservative influence over public life there, by this point in history it was not nearly as much a barrier to social and economic progress as traditional Islam still was in the Middle East. It is no coincidence that the Middle Eastern states that modernized most were the small handful where energetic westernizing autocrats—most famously Mustafa Kemal Ataturk of Turkey and Reza Khan Pahlavi of Persia (Iran)—defied the will of Muslim clerics, secularized their states, industrialized their economies and educational systems and, in Ataturk’s case, gave women the vote. By the early twentieth century, such fierce conflict with institutional religion was far less necessary for Latin America to modernize. In the Middle East, by contrast, it remains a struggle even today to balance modernization with respect for Islamic tradition.

Another comparison to consider is the prevalence of dictatorship in both regions during these years. Whether they were monarchs or autocratic strongmen, authoritarian leaders in both regions were often the agents of modernizing change. In the Middle East, the primary impulse for economic and social modernization was typically the will of determined authoritarians, such as the above-mentioned Ataturk and Pahlavi. Among the Latin American dictators who promoted industrialization and other modernizing changes were the Perons in Argentina and the Vargas government in Brazil. One last point that calls out for attention is the pronounced trend toward authoritarian rule worldwide during this period. A truly contextual view of this topic must take into account the rise of dictatorial or nondemocratic regimes in places like Asia (Japanese militarism during the 1930s, warlords and Chiang Kai-shek in China after the collapse of Sun Yat-sen’s democratic revolution) and Europe (most notably Lenin and Stalin in Russia, Mussolini in Italy, and Hitler in Germany). As with the regions discussed more directly by this question, dictatorship in these other places arose in some cases due to political and economic crises like the Depression, and in other cases due to pressures brought about by rapid modernization.

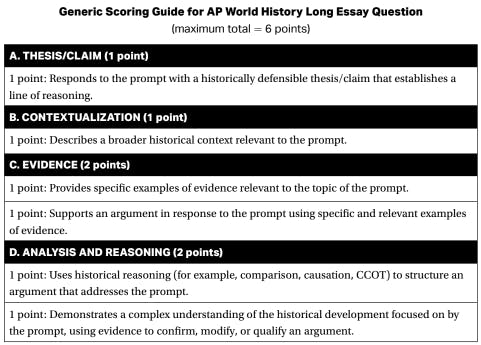

How is the Long Essay Question Scored?

The LEQ is less complicated than the DBQ, but certain tasks need to be accomplished the right way to earn a maximum score of six points. Below, we break down the scoring guide for the AP World History long essay question.

AP Biology Resources

- About the AP Biology Exam

- Top AP Biology Exam Strategies

- Top 5 Study Topics and Tips for the AP Biology Exam

- AP Biology Short Free-Response Questions

- AP Biology Long Free-Response Questions

AP Psychology Resources

- What’s Tested on the AP Psychology Exam?

- Top 5 Study Tips for the AP Psychology Exam

- AP Psychology Key Terms

- Top AP Psychology Exam Multiple-Choice Question Tips

- Top AP Psychology Exam Free Response Questions Tips

- AP Psychology Sample Free Response Question

AP English Language and Composition Resources

- What’s Tested on the AP English Language and Composition Exam?

- Top 5 Tips for the AP English Language and Composition Exam

- Top Reading Techniques for the AP English Language and Composition Exam

- How to Answer the AP English Language and Composition Essay Questions

- AP English Language and Composition Exam Sample Essay Questions

- AP English Language and Composition Exam Multiple-Choice Questions

AP Human Geography Resources

- What’s Tested On the AP Human Geography Exam?

- AP Human Geography FAQs

- AP Human Geography Question Types and Strategies

- Top 5 Study Tips for the AP Human Geography Exam

FOLLOW ALONG ON SOCIAL

Calculate for all schools

Your chance of acceptance, your chancing factors, extracurriculars, ap world history prompts.

Hey guys, I'm taking AP World History this year and I'm trying to get ahead on studying for the upcoming exam. Can anyone share their experience with the essay prompts or give me any advice on how to tackle them? Thanks!

Hello! It's great that you're preparing for the AP World History exam ahead of time. In the AP World History exam, there are two types of essays you'll need to write: the Long Essay Question (LEQ) and the Document-Based Question (DBQ).

For the LEQ, you'll be given a choice of three prompts, each asking you to develop an argument focused on a specific historical development, comparison, or continuity/change over time. To tackle the LEQ, follow these steps:

1. Carefully read and understand the prompt.

2. Brainstorm and outline your argument, organize your main points and supporting evidence.

3. Use relevant examples and evidence from the World History course to support your argument.

4. Make sure you address all parts of the prompt and present a clear and coherent argument.

For the DBQ, you'll be given a prompt and a set of documents to analyze. Your goal is to use the documents as evidence to support your argument in response to the prompt. Here's how to approach the DBQ:

1. Analyze the prompt: Understand what it's asking and identify the key elements you need to address.

2. Read and analyze the documents: Identify the author, the main point, and any bias or perspective present in each document.

3. Group the documents: Organize the documents by theme or topic, which will help you build a clear argument.

4. Develop your thesis: Form a clear and concise argument to answer the prompt, using the documents as evidence.

5. Write your essay: Include an introduction with your thesis, body paragraphs that discuss the documents and provide analysis, and a solid conclusion.

When practicing LEQ and DBQ essays, you can improve your skills by reviewing past prompts from the College Board website, adequately timing yourself, and seeking feedback from your teacher or peers. Remember that practice makes perfect, so the more you work on essay writing, the better prepared you'll be for the exam. Good luck!

About CollegeVine’s Expert FAQ

CollegeVine’s Q&A seeks to offer informed perspectives on commonly asked admissions questions. Every answer is refined and validated by our team of admissions experts to ensure it resonates with trusted knowledge in the field.

All Subjects

AP World History: Modern

How to Write the AP World LEQ

4 min read • Last Updated on July 11, 2024

Eric Beckman

Writing the AP World LEQ

⚡ Watch: AP World History - 🎥 Writing the LEQ

Choosing which long-essay question to write will be one of the last major decisions that students make for AP history this year. If a student understands all of the prompts, they should choose the topic for which they can think of the most evidence. The reason for focusing on evidence first is simple: Three is greater than two.

As I mentioned on in my May 2nd stream "Breaking Down the LEQ (replay on 🎥 the World History page ) quality paragraph based on evidence can net three points on the LEQ, which will certainly be near and probably be above the average score. A quality introduction, whether in one paragraph or two, can earn two points, one for thesis and one for context. Students should go for all five of these points if time allows, of course. But, I recommend drafting the body paragraph first, even though students will probably start their essay with a thesis and context, if they have time.

Looking at least year’s LEQ (on the last page of the Free-Response Questions ), differences in evidence points accounted for more than half of the difference in the average scores of questions two (0.9/1.8). Three (1.7/3.0) and four (1.3/2.4). Generating the most evidence possible is a key to maximizing students' LEQ scores. Not only will using two pieces effectively set up a base score of 2-3 on the LEQ, but using more evidence will help a student with contextualization and maybe even complexity.

The evidence point is usually the easiest to earn for the LEQ, and prepared students can double that point by explaining how their evidence supports an argument related to the prompt. Consider LEQ #2 from last year’s AP World History exam:

⚡ Watch: AP World History - 🎥 Practice on LEQ: Classical Era and Breaking the Prompt Down

“In the period c. 600 BCE to c. 600 CE, different factors led to the emergence and spread of new religions and belief systems, including Buddhism, Christianity, and Confucianism”

Develop an argument that evaluates how such factors led to the emergence or spread of one or more religions in this time period”

Here, an argument related to the prompt will involve a religion or religions and/or a factor related to them. A student could start by thinking about how religions emerged and spread, and then get specific. In order to function as evidence, facts need to be specific and relevant. For instance, with this question a student might start by identifying a religion and then considering how it emerged or spread. For instance, thinking about Confucianism, a student might remember that it began in China. “China” would not count as evidence, but something more specific, such as the Warring States Period or the Han Dynasty, would. Simply writing “The Han Dynasty in China supported Confucianism” is specific and accurate enough to count as one of the two required pieces of evidence. Next, the student would determine how or why the Han Dynasty did this, perhaps by explaining that Confucianism was an element of cultural unity supported by Han Emperors.

The student would then generate additional examples from the same religion or another. For example, they identify Christianity’s emergence and spread in the Roman Empire. Naming the Roman Empire is probably not specific enough, though it might count as context, but something specific from the Empire, such as Constantine, the Edict of Milan, or Christian martyrs would work. The student could combine these examples and their explanations into one paragraph. If the second piece of evidence is one another factor, such as trade routes, then the student has the basis for two smaller paragraphs.

Such a paragraph or paragraphs would yield a third point if the student demonstrate historical reasoning. This has two parts: showing historical thinking (causation, comparison, or analysis of continuity or change) and providing a reason. With question #2 above this requires explaining how something, such as empires, caused religions to emerge or spread. Writing “Empires caused religions to spread” is not enough, but “Religions spread within imperial societies, because some empires encouraged people to practice a particular religion in order to unite their society” would earn the point. Christianity in late Imperial Rome and Confucianism in Han would be evidence in support of this argument.

Once a student has drafted examples to be used as evidence and has an idea of how to demonstrate historical reasoning, they can either write it up or, if time allows, first write a thesis and contextualization. For more on thesis and contextualization see Kris Clancy’s excellent session (watch the replay on the 🎥 Skills Page ). Although they might write a thesis at the top of the essay, students can benefit by designing their response from the inside out: evidence first. Moreover, students who are almost out of time after writing their DBQ should consider writing one good body paragraph with evidence and reasoning, and thus earn three valuable points.

⚡ Watch: AP World History - 🎥 Sharpening Your LEQ Skills , LEQ Strategies , and More LEQ Practice

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

Ap® and sat® are trademarks registered by the college board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website., ap world dbq sourcing analysis practice & feedback.

- AP Calculus

- AP Chemistry

- AP U.S. History

- AP World History

- Free AP Practice Questions

- AP Exam Prep

AP World History: Sample DBQ Thesis Statements

Using the following documents, analyze how the Ottoman government viewed ethnic and religious groups within its empire for the period 1876–1908. Identify an additional document and explain how it would help you analyze the views of the Ottoman Empire.

Crafting a Solid Thesis Statement

Kaplan Pro Tip Your thesis can be in the first or last paragraph of your essay, but it cannot be split between the two. Many times, your original thesis is too simple to gain the point. A good idea is to write a concluding paragraph that might extend your original thesis. Think of a way to restate your thesis, adding information from your analysis of the documents.

Thesis Statements that Do NOT Work

There were many ways in which the Ottoman government viewed ethnic and religious groups.

The next statement paraphrases the historical background and does not address the question. It would not receive credit for being a thesis.

The Ottoman government brought reforms in the Constitution of 1876. The empire had a number of different groups of people living in it, including Christians and Muslims who did not practice the official form of Islam. By 1908 a new government was created by the Young Turks and the sultan was soon out of his job.

This next sentence gets the question backward: you are being asked for the government’s view of religious and ethnic groups, not the groups’ view of the government. Though the point-of-view issue is very important, this statement would not receive POV credit.

People of different nationalities reacted differently to the Ottoman government depending on their religion.

The following paragraph says a great deal about history, but it does not address the substance of the question. It would not receive credit because of its irrelevancy.

Throughout history, people around the world have struggled with the issue of political power and freedom. From the harbor of Boston during the first stages of the American Revolution to the plantations of Haiti during the struggle to end slavery, people have battled for power. Even in places like China with the Boxer Rebellion, people were responding against the issue of Westernization. Imperialism made the demand for change even more important, as European powers circled the globe and stretched their influences to the far reaches of the known world. In the Ottoman Empire too, people demanded change.

Thesis Statements that DO Work

Now we turn to thesis statements that do work. These two sentences address both the religious and ethnic aspects of the question. They describe how these groups were viewed.

The Ottoman government took the same position on religious diversity as it did on ethnic diversity. Minorities were servants of the Ottoman Turks, and religious diversity was allowed as long as Islam remained supreme.

This statement answers the question in a different way but is equally successful.

Government officials in the Ottoman Empire sent out the message that all people in the empire were equal regardless of religion or ethnicity, yet the reality was that the Turks and their version of Islam were superior.

Going Beyond the Basic Requirements

- have a highly sophisticated thesis

- show deep analysis of the documents

- use documents persuasively in broad conceptual ways

- analyze point of view thoughtfully and consistently

- identify multiple additional documents with sophisticated explanations of their usefulness

- bring in relevant outside information beyond the historical background provided

Final Notes on How to Write the DBQ

- Take notes in the margins during the reading period relating to the background of the speaker and his/her possible point of view.

- Assume that each document provides only a snapshot of the topic—just one perspective.

- Look for connections between documents for grouping.

- In the documents booklet, mark off documents that you use so that you do not forget to mention them.

- As you are writing, refer to the authorship of the documents, not just the document numbers.

- Mention additional documents and the reasons why they would help further analyze the question.

- Mark off each part of the instructions for the essay as you accomplish them.

- Use visual and graphic information in documents that are not text-based.

Don’t

- Repeat information from the historical background in your essay.

- Assume that the documents are universally valid rather than presenting a single perspective.

- Spend too much time on the DBQ rather than moving on to the other essay.

- Write the first paragraph before you have a clear idea of what your thesis will be.

- Ignore part of the question.

- Structure the essay with just one paragraph.

- Underline or highlight the thesis. (This may be done as an exercise for class, but it looks juvenile on the exam.)

You might also like

Call 1-800-KAP-TEST or email [email protected]

Prep for an Exam

MCAT Test Prep

LSAT Test Prep

GRE Test Prep

GMAT Test Prep

SAT Test Prep

ACT Test Prep

DAT Test Prep

NCLEX Test Prep

USMLE Test Prep

Courses by Location

NCLEX Locations

GRE Locations

SAT Locations

LSAT Locations

MCAT Locations

GMAT Locations

Useful Links

Kaplan Test Prep Contact Us Partner Solutions Work for Kaplan Terms and Conditions Privacy Policy CA Privacy Policy Trademark Directory

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

The Best AP World History Notes to Study With

Advanced Placement (AP)

AP World History is a fascinating survey of the evolution of human civilization from 1200 CE to the present. Because it spans almost 1,000 years and covers massive changes in power, culture, and technology across the globe, it might seem like an overwhelming amount of info to remember for one test.

This article will help you organize your studying by providing links to online AP World History notes and advice on how to use these notes to structure and execute a successful study plan.

How to Use These AP World History Notes

The notes in this article will help you review all the information you need to know for the AP World History exam. If you are missing any notes from class or just looking for a more organized run-through of the curriculum, you can use this guide as a reference.

During your first semester of AP World History, study the content in the notes that your class has already covered. I'd recommend conducting a holistic review of everything you've learned so far about once a month so that you don't start to forget information from the beginning of the course.

In the second semester, after you've made it through most of the course, you should use these notes in conjunction with practice tests . Taking (realistically timed) practice tests will help verify that you've absorbed the information.

After each test, assess your mistakes and take note of where you came up short. Then, focus your studying on the notes that are most relevant to your weak content areas . Once you feel more confident, take and score another practice test to see whether you've improved. You can repeat this process until you're satisfied with your scores!

Background: AP World History Themes and Units

Before we dive into the content of the AP World History test, it's important to note that the exam underwent some significant changes in the 2019-20 school year . From now on, the test will focus on the modern era (1200 CE to the present) , covering a much smaller period of time. As such, its name has been changed to AP World History: Modern (a World History: Ancient course and exam are currently in development).

Other than this major content change, the format of the exam will remain the same (since 2018).

Now then, what exactly is tested on AP World History? Both the course and exam are divided into six themes and nine units.

Here are the current World History themes:

- Theme 1: Humans and the Environment

- Theme 2: Cultural Developments and Interactions

- Theme 3: Governance

- Theme 4: Economic Systems

- Theme 5: Social Interactions and Organization

- Theme 6: Technology and Innovation

And here are the units as well as how much of the test they make up, percentage-wise:

Source: AP World History Course and Exam Description, 2019-20

You should examine all content through the lens of these themes and units. AP World History is mostly about identifying large trends that occur over long periods of time. In the next section, I'll go through the different time periods covered in the curriculum, with links to online notes.

AP World History Notes

The following AP World History notes are organized by unit. There are both overall notes for each unit as well as notes focusing on almost all of the individual subunits.

Unit 1: The Global Tapestry (1200 to 1450)

Overall Notes

Unit 2: Networks of Exchange (1200-1450)

Unit 3: land-based empires (1450-1750), unit 4: transoceanic interconnections (1450-1750), unit 5: revolutions (1750-1900), unit 6: consequences of industrialization (1750-1900), unit 7: global conflict (1900-present), unit 8: cold war and decolonization (1900-present), unit 9: globalization (1900-present).

AP World History Exam: 4 Essential Study Tips

Here are a few study tips that will help you prepare strategically for the AP World History exam. In addition to these tidbits of advice, you can check out this article with a longer list of the best study tips for this class .

#1: We All Scream for Historical Themes

I'm sure you've been screaming with delight throughout your entire reading of this article because the themes are so thrilling. Seriously, though, they're super important for doing well on the final exam. Knowledge of specific facts about different empires and regions throughout history will be of little use on the test if you can't weave that information together to construct a larger narrative.

As you look through the notes, think carefully about how everything connects back to the six major themes of the course .

For example, if you're reading about the expansion of long-distance trade networks in the early modern period, you might start to think about how these new exchanges impacted the natural environment (theme 1). If you get into this mode of thinking early, you'll have an easier time writing high-quality essays on the final exam.

#2: Practice Outlining Essays (Especially the DBQ)

It's critical to write well-organized, coherent essays on the World History test , but statistics indicate that a large majority of students struggle with this aspect of the exam.

In 2021, results from the DBQ scoring looked like this:

- 79% of students earned the thesis point

- 30% of students earned the contextualization point

- Evidence: 11% of students earned all 3 evidence points; 41% earned 2 points; 40% earned 1 point; 8% earned 0 points

- Analysis & Reasoning: 2% earned 2 points; 15% earned 1 point; 83% earned 0 points

So clearly, it can be tough to do well on the DBQ. However, I guarantee you can score well on the DBQ and other essay questions if you consistently practice writing outlines that follow the instructions and stay focused on the main topic. Try to become a pro at planning out your ideas by the time the exam rolls around.

#3: Know Your Chronology

You don't need to memorize a ton of exact dates, but you do need to be aware of the basic order in which major events happened in each region of the world . If someone tells you the name of an empire or dynasty, you should know which centuries it was active and what caused its rise and fall.

Pay attention to the overall developments that occurred in world history during each period designated by the course. What types of contact were made between different regions? Where were trading networks established? What were the dominant powers?

Multiple-choice and essay questions will ask you to focus on certain time periods and regions, so you should know the gist of what was going on at any given juncture.

#4: Don't Sweat the Small Stuff

It's not necessary to know the names of every single region in a particular empire and the exact dates when they were conquered. You're not expected to have a photographic memory. AP World History is mostly about broad themes.

You should still include a few specific details in your essays to back up your main points, but that's not nearly as important as showing a deep understanding of the progression of human history on a larger scale.

Conclusion: How to Study With AP World History Notes

A well-organized set of notes can help ground your studying for AP World History. With so much content to cover, it's best to selectively revisit different portions of the course based on where you find the largest gaps in your knowledge . You can decide what you need to study based on which content areas cause you the most trouble on practice tests.

Here are some tips to keep in mind while studying the above AP World History notes:

- Connect facts back to the themes

- Practice writing essay outlines

- Know the basic chronology of events

- Don't worry too much about small details

If you meticulously comb through your mistakes and regularly practice your essay-writing skills, you'll be on the right track to a great AP World History score!

What's Next?

What's a document-based question? How do you write a good response? Read this article to learn more about the most challenging question on the AP World History test .

If you're taking AP World History during your freshman or sophomore year, check out this article for some advice on which history classes you should take for the rest of your time in high school.

How many AP classes should you take in high school? We'll help you figure out how many AP classes you should take based on your goals and the course offerings at your school.

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Samantha is a blog content writer for PrepScholar. Her goal is to help students adopt a less stressful view of standardized testing and other academic challenges through her articles. Samantha is also passionate about art and graduated with honors from Dartmouth College as a Studio Art major in 2014. In high school, she earned a 2400 on the SAT, 5's on all seven of her AP tests, and was named a National Merit Scholar.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

- EXPLORE Random Article

- Happiness Hub

How to Write Good Essays in AP World History

Last Updated: September 1, 2021

This article was co-authored by Carrie Adkins, PhD . Carrie Adkins is the cofounder of NursingClio, an open access, peer-reviewed, collaborative blog that connects historical scholarship to current issues in gender and medicine. She completed her PhD in American History at the University of Oregon in 2013. While completing her PhD, she earned numerous competitive research grants, teaching fellowships, and writing awards. This article has been viewed 41,823 times.

AP World History is an exciting course to take. You can learn about how civilizations have grown and interacted with one another from the time of 600 B.C.E. to the present day. For your course and AP exam, you will need to write three kinds of essays: document-based, continuity and change-over-time, and comparative. [1] X Research source Each has a slightly different format so be aware of the differences.

Writing a Document-Based Essay

- Making historical arguments from evidence and practicing historical argumentation

- Chronological reasoning, determining causation, continuity, and change-over-time

- Comparison and contextualization

- Historical interpretation and synthesis [2] X Research source

- Look for commonalities or contrasts in the documents’ tone, authorship, purpose or intent, and dating. [4] X Research source

- Draw a table that lists your group headings, e.g. "gender" or "trade pacts." List the numbers of the documents that fit in each group. For each group, make sure you have minimally two documents. [5] X Research source

- Themes might include a particular time period like World War II, technological movements like the Industrial Revolution, or social movements like civil rights.

- You must use all or all but one of the documents. [7] X Research source For this essay, rely on the evidence in front of you first. Then, if you have any examples that will help your point, you can incorporate them into your argument.

- You might be asked what other documents could be beneficial to your grouping or argument. Think about what could make your arguments stronger. Try to mention an additional needed document at the end of every body paragraph. [8] X Research source

- For tips on writing an essay, see Write an Essay.

- For advice on developing your thesis statement, see Focus an Essay. Your thesis statement should mention evidence you gathered from the documents. It should clearly and concisely answer the prompt. Do not take on a thesis that you cannot prove in the allotted time. A framework for a thesis could be: "Docs. 1-3 demonstrate how due to the invention of the water mill, landowners with water rights were able to extract income from a basic natural resource. This widened the income gap between landowners and farmers."

- For examples of sample questions and documents for this essay and the other types of essays, see http://media.collegeboard.com/digitalServices/pdf/ap/ap-world-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

Penning a Change-Over-Time Essay

- How did environmental conditions shift, for example, during the Industrial Revolution? What were the connections to technological development? Look for changes over time and things that remained the same or were continuous.

- Include dates when relevant. [11] X Research source

- When forming your thesis statement, make sure it answers the prompt and mentions both change and continuity. For example, "Although Christianity spread through colonialism, its impact in China was relatively small in comparison to other countries (e.g. X, Y, Z). In China, Buddhism remained as a mainstay because of missionaries' inability to connect with the local people in (location M, N, etc.)."

- For example, if you are writing about the Crusades, drawing parallels to the Mongols and spirituality's influence on their wars is an interesting side-point. Unless you were asked to compare the role of religion in war, however, the point is probably not necessary to mention!

- Good essays tie change and continuity together. For example, an important agricultural change could lead to a technological innovation that becomes a continuity.

Mastering a Comparative Essay

- You might be able to choose from a number of examples for analysis. [13] X Research source

- Assess or evaluate

- Describe [14] X Research source

- For example, if the prompt asks you to compare the role of religion in war between two societies, you could pick the Ancient Hebrews and early Muslims. If, however, you know more about the Christian Crusaders and the spiritualist Mongols, go for that comparison. As long as you can support your points with thorough examples and your examples answer the question at hand, use what you know best.

- Can develop a solid thesis

- Answer every part of the question

- Provide evidence to back up your thesis

- Make minimally one (preferably more) direct comparisons between regions or societies

- Examine one reason for the difference between regions

Expert Q&A

- Use an active voice (versus passive) and simple past verbs. [15] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- If you have time, always review your essay after you’ve written it. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- To ensure good essay writing, be sure to study enough beforehand. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://media.collegeboard.com/digitalServices/pdf/ap/ap-world-history-course-and-exam-description.pdf

- ↑ http://glencoe.mheducation.com/sites/dl/free/0024122010/899891/AP_World_History_Essay_Writers_HB.pdf

- ↑ http://faculty.chass.ncsu.edu/slatta/hi216/write.htm

About this article

Reader Success Stories

Oct 15, 2017

Did this article help you?

- About wikiHow

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

AP® World History

The 5 most important historical thinking skills for the ap® world history test.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: March 1, 2022

When you finally sit down and begin the AP® World History Exam, you will have invested a lot of time, effort, and energy in preparing for that moment. Having a plan of attack for each question is key to getting the maximum number of points for that question. One of your best bets is to make sure that you have developed solid historical thinking skills .

This AP® World History review will outline and discuss the nine historical thinking skills that are central to the study and practice of history. We will then discuss the five most important of those skills needed to excel on the exam. We will also arm you with the strategies needed for spotting these skills on the exam, how to use them to analyze a primary source critically, and how you can include them in your own writing.

Historical Thinking Skills and the AP® World History Exam

As an AP® student, you are expected to have mastered historical thinking skills because every question on the exam will require you to apply one or more of them. Even though every exam question assesses one or more of the skill-based proficiency expectations, historical thinking skills are best put into practice on the Short-Answer, Document-Based and Long Essay Questions (SAQs, DBQs, and LEQs).

These three sections make up 60% of the overall AP® World History total exam score. Do we have your attention? You can see clearly that the CollegeBoard wants you to use those historical thinking skills on the exam.

Historical Thinking Skills and AP® World History Writing Questions

Short-answer questions.

SAQs will address one or more of themes of the course. You will have to use your historical thinking skills to respond to primary and secondary sources, a historian’s argument, non-textual sources (maps or charts), or general suggestions about world history. Each question will ask you to identify and explore examples of historical evidence relevant to the source or question.

Document-Based Question

The DBQ measures your ability to analyze and integrate historical data and to assess verbal, quantitative, or visual evidence. Your responses will be judged on your ability to formulate a thesis and back it up with relevant evidence. The documents included in the DBQ can vary in length and format, and the question content can include charts, graphs, cartoons, and pictures, as well as written materials.

You are expected to be able to assess the value of different kinds of documents, and you’ll be required to relate the material to a historical period or theme, thus focusing on major periods and issues. Therefore, it is crucial to have knowledge beyond the particular focus of the question and to incorporate it into your essay to get the highest score.

Long Essay Question

You are given a chance to show what you know best on the LEQs by having a choice between two long essay options. The LEQs will measure how you use your historical thinking skills to explain and analyze significant issues in the world history themes from the course. Your essays must include a central issue or argument that you need to support by evaluating specific and relevant historical evidence using specific in-depth examples of large-scale events taken from the course, or classroom discussion.

What are the Nine Historical Thinking Skills?

The CollegeBoard, in its Rubrics for AP® Histories , tells you that the AP® history courses are designed to “apprentice” you in the practice of history, emphasizing the development of historical thinking skills as you learn about world history. To accomplish this, the CollegeBoard has come up with nine historical thinking skills that will be evaluated on the AP® World History exam.

So, how do you go about developing historical thinking skills? Students of history do this by investigating the past, particularly through exploring and interpreting primary sources and secondary texts. You further refine those skills through the regular development of historical argumentation in writing.

The nine historical thinking skills are grouped into four categories: Analyzing Historical Sources and Evidence, Making Historical Connections, Chronological Reasoning, and Creating and Supporting a Historical Argument.

Analyzing Historical Sources and Evidence

You can best develop your historical thinking skills by analyzing an assortment of primary and secondary sources. Being exposed to a variety of diverse views builds your ability to evaluate the effectiveness of different types of arguments.

Content and Sourcing of Primary Sources – This involves the ability to describe, select, and evaluate relevant evidence about the past from many different sources. When you analyze a source, you should not just think about the content of the source, but you should also look at the interaction between the content and the authorship, vantage point, purpose, audience, format, and historical context of the source. You can then evaluate the usefulness, reliability, and limitations of the source as historical evidence.

Interpreting Secondary Sources – This skill requires you to use secondary sources to describe, analyze, and evaluate the ways that the past is interpreted. This includes understanding the types of questions that are asked, as well as considering how the particular circumstances and contexts in which historians work and write shape their interpretations of past events and historical evidence.

Making Historical Connections

Comparison – This skill involves your ability to identify, compare, and evaluate multiple perspectives on a given historical event so you can make conclusions about that event. This skill also requires the ability to describe, compare, and assess several historical developments within one society, between different cultures, and in diverse chronological and geographical contexts. Comparisons can also be made across different time periods and geographical locations, and between contrasting historical events within the same time period or geographical area.

Contextualization – This skill relates your ability to connect historical events and processes to particular circumstances of time and place, including broader regional, national, or global activities. You will need to determine past events or developments within the wider context in which they occurred and then draw conclusions about their significance.

Synthesis – This skill may be the most challenging of all the thinking skills in the AP® World History course and can be mastered only after spending some time as a professional historian. There are ways that you, as an AP® student, can show your proficiency in the skill of synthesis.

For example, you can make meaningful and persuasive historical connections between one historical issue and other historical issue and similar developments in a different historical context, geographical area, or era, including the present. You can also connect different course themes or approaches to history (e.g., political, social, or cultural) for a given historical issue. Finally, you can use views from an entirely different discipline like economics, art history or anthropology, to better understand a particular historical point.

As an AP® World History student, your essays should include a combination of diverse and conflicting evidence with differing interpretations in an essay to show a well-thought out and convincing understanding of the past.

Chronological Reasoning

Causation – This skill relates to your ability to identify, analyze, and evaluate the relationships among historical causes and effects. You also must tell the difference between those that are long-term and proximate. You should also know the difference between causation and correlation to master this skill.

Patterns of Continuity and Change over Time – This is your ability to recognize, analyze, and assess the dynamics of continuity and change over periods of time of different lengths, as well as your ability to relate these patterns to a broader historical processes or themes.

Periodization – This is your ability to describe, analyze, and evaluate different ways that history is divided into periods. Various models of periodization are often debated among historians, and the choice of specific turning points or starting and ending dates might garner a higher value to one region or group than to another.

Creating and Supporting a Historical Argument

Argumentation – This involves your ability to create an argument and support it using relevant historical evidence. This includes identifying and framing a question about the past and then coming up with a claim or argument about that question, usually in the form of a thesis.

A good argument requires a defensible thesis, supported by thorough analysis of pertinent and varied historical evidence. The evidence used should be built around the application of one of the other historical thinking skills like comparison, causation, patterns of continuity and change over time, or periodization.