An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Research questions, hypotheses and objectives

Patricia farrugia , bscn, bradley a petrisor , msc, md, forough farrokhyar , mphil, phd, mohit bhandari , md, msc.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondance to: Dr. M. Bhandari, 293 Wellington St. N, Ste. 110, Division of Orthopaedic Surgery, McMaster University, Hamilton ON L8L 2X2, [email protected]

Accepted 2009 Jan 27.

There is an increasing familiarity with the principles of evidence-based medicine in the surgical community. As surgeons become more aware of the hierarchy of evidence, grades of recommendations and the principles of critical appraisal, they develop an increasing familiarity with research design. Surgeons and clinicians are looking more and more to the literature and clinical trials to guide their practice; as such, it is becoming a responsibility of the clinical research community to attempt to answer questions that are not only well thought out but also clinically relevant. The development of the research question, including a supportive hypothesis and objectives, is a necessary key step in producing clinically relevant results to be used in evidence-based practice. A well-defined and specific research question is more likely to help guide us in making decisions about study design and population and subsequently what data will be collected and analyzed. 1

Objectives of this article

In this article, we discuss important considerations in the development of a research question and hypothesis and in defining objectives for research. By the end of this article, the reader will be able to appreciate the significance of constructing a good research question and developing hypotheses and research objectives for the successful design of a research study. The following article is divided into 3 sections: research question, research hypothesis and research objectives.

Research question

Interest in a particular topic usually begins the research process, but it is the familiarity with the subject that helps define an appropriate research question for a study. 1 Questions then arise out of a perceived knowledge deficit within a subject area or field of study. 2 Indeed, Haynes suggests that it is important to know “where the boundary between current knowledge and ignorance lies.” 1 The challenge in developing an appropriate research question is in determining which clinical uncertainties could or should be studied and also rationalizing the need for their investigation.

Increasing one’s knowledge about the subject of interest can be accomplished in many ways. Appropriate methods include systematically searching the literature, in-depth interviews and focus groups with patients (and proxies) and interviews with experts in the field. In addition, awareness of current trends and technological advances can assist with the development of research questions. 2 It is imperative to understand what has been studied about a topic to date in order to further the knowledge that has been previously gathered on a topic. Indeed, some granting institutions (e.g., Canadian Institute for Health Research) encourage applicants to conduct a systematic review of the available evidence if a recent review does not already exist and preferably a pilot or feasibility study before applying for a grant for a full trial.

In-depth knowledge about a subject may generate a number of questions. It then becomes necessary to ask whether these questions can be answered through one study or if more than one study needed. 1 Additional research questions can be developed, but several basic principles should be taken into consideration. 1 All questions, primary and secondary, should be developed at the beginning and planning stages of a study. Any additional questions should never compromise the primary question because it is the primary research question that forms the basis of the hypothesis and study objectives. It must be kept in mind that within the scope of one study, the presence of a number of research questions will affect and potentially increase the complexity of both the study design and subsequent statistical analyses, not to mention the actual feasibility of answering every question. 1 A sensible strategy is to establish a single primary research question around which to focus the study plan. 3 In a study, the primary research question should be clearly stated at the end of the introduction of the grant proposal, and it usually specifies the population to be studied, the intervention to be implemented and other circumstantial factors. 4

Hulley and colleagues 2 have suggested the use of the FINER criteria in the development of a good research question ( Box 1 ). The FINER criteria highlight useful points that may increase the chances of developing a successful research project. A good research question should specify the population of interest, be of interest to the scientific community and potentially to the public, have clinical relevance and further current knowledge in the field (and of course be compliant with the standards of ethical boards and national research standards).

FINER criteria for a good research question

Adapted with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health. 2

Whereas the FINER criteria outline the important aspects of the question in general, a useful format to use in the development of a specific research question is the PICO format — consider the population (P) of interest, the intervention (I) being studied, the comparison (C) group (or to what is the intervention being compared) and the outcome of interest (O). 3 , 5 , 6 Often timing (T) is added to PICO ( Box 2 ) — that is, “Over what time frame will the study take place?” 1 The PICOT approach helps generate a question that aids in constructing the framework of the study and subsequently in protocol development by alluding to the inclusion and exclusion criteria and identifying the groups of patients to be included. Knowing the specific population of interest, intervention (and comparator) and outcome of interest may also help the researcher identify an appropriate outcome measurement tool. 7 The more defined the population of interest, and thus the more stringent the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the greater the effect on the interpretation and subsequent applicability and generalizability of the research findings. 1 , 2 A restricted study population (and exclusion criteria) may limit bias and increase the internal validity of the study; however, this approach will limit external validity of the study and, thus, the generalizability of the findings to the practical clinical setting. Conversely, a broadly defined study population and inclusion criteria may be representative of practical clinical practice but may increase bias and reduce the internal validity of the study.

PICOT criteria 1

A poorly devised research question may affect the choice of study design, potentially lead to futile situations and, thus, hamper the chance of determining anything of clinical significance, which will then affect the potential for publication. Without devoting appropriate resources to developing the research question, the quality of the study and subsequent results may be compromised. During the initial stages of any research study, it is therefore imperative to formulate a research question that is both clinically relevant and answerable.

Research hypothesis

The primary research question should be driven by the hypothesis rather than the data. 1 , 2 That is, the research question and hypothesis should be developed before the start of the study. This sounds intuitive; however, if we take, for example, a database of information, it is potentially possible to perform multiple statistical comparisons of groups within the database to find a statistically significant association. This could then lead one to work backward from the data and develop the “question.” This is counterintuitive to the process because the question is asked specifically to then find the answer, thus collecting data along the way (i.e., in a prospective manner). Multiple statistical testing of associations from data previously collected could potentially lead to spuriously positive findings of association through chance alone. 2 Therefore, a good hypothesis must be based on a good research question at the start of a trial and, indeed, drive data collection for the study.

The research or clinical hypothesis is developed from the research question and then the main elements of the study — sampling strategy, intervention (if applicable), comparison and outcome variables — are summarized in a form that establishes the basis for testing, statistical and ultimately clinical significance. 3 For example, in a research study comparing computer-assisted acetabular component insertion versus freehand acetabular component placement in patients in need of total hip arthroplasty, the experimental group would be computer-assisted insertion and the control/conventional group would be free-hand placement. The investigative team would first state a research hypothesis. This could be expressed as a single outcome (e.g., computer-assisted acetabular component placement leads to improved functional outcome) or potentially as a complex/composite outcome; that is, more than one outcome (e.g., computer-assisted acetabular component placement leads to both improved radiographic cup placement and improved functional outcome).

However, when formally testing statistical significance, the hypothesis should be stated as a “null” hypothesis. 2 The purpose of hypothesis testing is to make an inference about the population of interest on the basis of a random sample taken from that population. The null hypothesis for the preceding research hypothesis then would be that there is no difference in mean functional outcome between the computer-assisted insertion and free-hand placement techniques. After forming the null hypothesis, the researchers would form an alternate hypothesis stating the nature of the difference, if it should appear. The alternate hypothesis would be that there is a difference in mean functional outcome between these techniques. At the end of the study, the null hypothesis is then tested statistically. If the findings of the study are not statistically significant (i.e., there is no difference in functional outcome between the groups in a statistical sense), we cannot reject the null hypothesis, whereas if the findings were significant, we can reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternate hypothesis (i.e., there is a difference in mean functional outcome between the study groups), errors in testing notwithstanding. In other words, hypothesis testing confirms or refutes the statement that the observed findings did not occur by chance alone but rather occurred because there was a true difference in outcomes between these surgical procedures. The concept of statistical hypothesis testing is complex, and the details are beyond the scope of this article.

Another important concept inherent in hypothesis testing is whether the hypotheses will be 1-sided or 2-sided. A 2-sided hypothesis states that there is a difference between the experimental group and the control group, but it does not specify in advance the expected direction of the difference. For example, we asked whether there is there an improvement in outcomes with computer-assisted surgery or whether the outcomes worse with computer-assisted surgery. We presented a 2-sided test in the above example because we did not specify the direction of the difference. A 1-sided hypothesis states a specific direction (e.g., there is an improvement in outcomes with computer-assisted surgery). A 2-sided hypothesis should be used unless there is a good justification for using a 1-sided hypothesis. As Bland and Atlman 8 stated, “One-sided hypothesis testing should never be used as a device to make a conventionally nonsignificant difference significant.”

The research hypothesis should be stated at the beginning of the study to guide the objectives for research. Whereas the investigators may state the hypothesis as being 1-sided (there is an improvement with treatment), the study and investigators must adhere to the concept of clinical equipoise. According to this principle, a clinical (or surgical) trial is ethical only if the expert community is uncertain about the relative therapeutic merits of the experimental and control groups being evaluated. 9 It means there must exist an honest and professional disagreement among expert clinicians about the preferred treatment. 9

Designing a research hypothesis is supported by a good research question and will influence the type of research design for the study. Acting on the principles of appropriate hypothesis development, the study can then confidently proceed to the development of the research objective.

Research objective

The primary objective should be coupled with the hypothesis of the study. Study objectives define the specific aims of the study and should be clearly stated in the introduction of the research protocol. 7 From our previous example and using the investigative hypothesis that there is a difference in functional outcomes between computer-assisted acetabular component placement and free-hand placement, the primary objective can be stated as follows: this study will compare the functional outcomes of computer-assisted acetabular component insertion versus free-hand placement in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. Note that the study objective is an active statement about how the study is going to answer the specific research question. Objectives can (and often do) state exactly which outcome measures are going to be used within their statements. They are important because they not only help guide the development of the protocol and design of study but also play a role in sample size calculations and determining the power of the study. 7 These concepts will be discussed in other articles in this series.

From the surgeon’s point of view, it is important for the study objectives to be focused on outcomes that are important to patients and clinically relevant. For example, the most methodologically sound randomized controlled trial comparing 2 techniques of distal radial fixation would have little or no clinical impact if the primary objective was to determine the effect of treatment A as compared to treatment B on intraoperative fluoroscopy time. However, if the objective was to determine the effect of treatment A as compared to treatment B on patient functional outcome at 1 year, this would have a much more significant impact on clinical decision-making. Second, more meaningful surgeon–patient discussions could ensue, incorporating patient values and preferences with the results from this study. 6 , 7 It is the precise objective and what the investigator is trying to measure that is of clinical relevance in the practical setting.

The following is an example from the literature about the relation between the research question, hypothesis and study objectives:

Study: Warden SJ, Metcalf BR, Kiss ZS, et al. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound for chronic patellar tendinopathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Rheumatology 2008;47:467–71.

Research question: How does low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) compare with a placebo device in managing the symptoms of skeletally mature patients with patellar tendinopathy?

Research hypothesis: Pain levels are reduced in patients who receive daily active-LIPUS (treatment) for 12 weeks compared with individuals who receive inactive-LIPUS (placebo).

Objective: To investigate the clinical efficacy of LIPUS in the management of patellar tendinopathy symptoms.

The development of the research question is the most important aspect of a research project. A research project can fail if the objectives and hypothesis are poorly focused and underdeveloped. Useful tips for surgical researchers are provided in Box 3 . Designing and developing an appropriate and relevant research question, hypothesis and objectives can be a difficult task. The critical appraisal of the research question used in a study is vital to the application of the findings to clinical practice. Focusing resources, time and dedication to these 3 very important tasks will help to guide a successful research project, influence interpretation of the results and affect future publication efforts.

Tips for developing research questions, hypotheses and objectives for research studies

Perform a systematic literature review (if one has not been done) to increase knowledge and familiarity with the topic and to assist with research development.

Learn about current trends and technological advances on the topic.

Seek careful input from experts, mentors, colleagues and collaborators to refine your research question as this will aid in developing the research question and guide the research study.

Use the FINER criteria in the development of the research question.

Ensure that the research question follows PICOT format.

Develop a research hypothesis from the research question.

Develop clear and well-defined primary and secondary (if needed) objectives.

Ensure that the research question and objectives are answerable, feasible and clinically relevant.

FINER = feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, relevant; PICOT = population (patients), intervention (for intervention studies only), comparison group, outcome of interest, time.

Competing interests: No funding was received in preparation of this paper. Dr. Bhandari was funded, in part, by a Canada Research Chair, McMaster University.

- 1. Brian Haynes R. Forming research questions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:881–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.06.006. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Hulley S, Cummings S, Browner W, et al. Designing clinical research. 3rd ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Sackett D, Strauss S, Richardson W, et al. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach evidence-based medicine. 2nd ed. Edinburgh (UK): Churchill Livingstone; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Fisher CG, Wood KB. Introduction to and techniques of evidence-based medicine. Spine. 2007;32(Suppl):S66–72. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318145308d. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Guyatt GH, et al. Clinical epidemiology: how to do clinical practice research. 3rd ed. New York (NY): Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Guyatt G, Rennie D. User’s guide to medical research: a manual for evidence-based clinical practice. 3rd ed. Chicago (IL): AMA Press Printing; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Hanson BP. Designing, conducting and reporting clinical research. A step by step approach. Injury. 2006;37:583–94. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2005.06.051. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Bland JM, Altman DG. One and two sided tests of significance. BMJ. 1994;309:248. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6949.248. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Freedman B. Equipoise and the ethics of clinical research. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:141–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198707163170304. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- PDF (147.1 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Scientific Hypotheses: Writing, Promoting, and Predicting Implications

Affiliations.

- 1 Departments of Rheumatology and Research and Development, Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust (Teaching Trust of the University of Birmingham, UK), Russells Hall Hospital, Dudley, West Midlands, UK. [email protected].

- 2 Department of Medical Chemistry, Yerevan State Medical University, Yerevan, Armenia.

- 3 Department of Surgical Disciplines, South Kazakhstan Medical Academy, Shymkent, Kazakhstan.

- 4 Department of Biology and Biochemistry, South Kazakhstan Medical Academy, Shymkent, Kazakhstan.

- 5 Departments of Rheumatology and Research and Development, Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust (Teaching Trust of the University of Birmingham, UK), Russells Hall Hospital, Dudley, West Midlands, UK.

- 6 Arthritis Research UK Epidemiology Unit, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK.

- PMID: 31760713

- PMCID: PMC6875436

- DOI: 10.3346/jkms.2019.34.e300

Scientific hypotheses are essential for progress in rapidly developing academic disciplines. Proposing new ideas and hypotheses require thorough analyses of evidence-based data and predictions of the implications. One of the main concerns relates to the ethical implications of the generated hypotheses. The authors may need to outline potential benefits and limitations of their suggestions and target widely visible publication outlets to ignite discussion by experts and start testing the hypotheses. Not many publication outlets are currently welcoming hypotheses and unconventional ideas that may open gates to criticism and conservative remarks. A few scholarly journals guide the authors on how to structure hypotheses. Reflecting on general and specific issues around the subject matter is often recommended for drafting a well-structured hypothesis article. An analysis of influential hypotheses, presented in this article, particularly Strachan's hygiene hypothesis with global implications in the field of immunology and allergy, points to the need for properly interpreting and testing new suggestions. Envisaging the ethical implications of the hypotheses should be considered both by authors and journal editors during the writing and publishing process.

Keywords: Bibliographic Databases; Hypothesis; Impact; Peer Review; Research Ethics; Writing.

© 2019 The Korean Academy of Medical Sciences.

Publication types

- Peer Review, Research* / ethics

- Publishing* / ethics

- Social Media

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

The energetics of genome complexity

- William Martin

Evidence for an early prokaryotic endosymbiosis

- James A. Lake

A hierarchical model for evolution of 23S ribosomal RNA

- Konstantin Bokov

- Sergey V. Steinberg

The equilibria that allow bacterial persistence in human hosts

- Martin J. Blaser

- Denise Kirschner

Introns and the origin of nucleus–cytosol compartmentalization

- Eugene V. Koonin

Developmental plasticity and human health

- Patrick Bateson

- David Barker

- Sonia E. Sultan

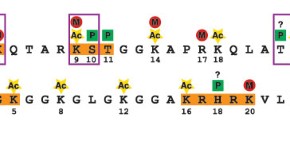

Binary switches and modification cassettes in histone biology and beyond

- Wolfgang Fischle

- Yanming Wang

- C. David Allis

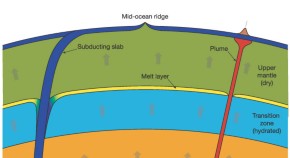

Whole-mantle convection and the transition-zone water filter

- David Bercovici

- Shun-ichiro Karato

The transorientation hypothesis for codon recognition during protein synthesis

- Anne B. Simonson

Cause of neural death in neurodegenerative diseases attributable to expansion of glutamine repeats

- M. F. Perutz

- A. H. Windle

Inferring the statistical interpretation of quantum mechanics from the classical limit

- Kurt Gottfried

The origins of insect metamorphosis

- James W. Truman

- Lynn M. Riddiford

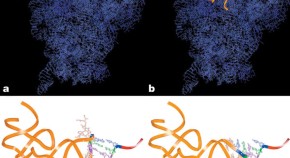

The hydrogen hypothesis for the first eukaryote

- Miklós Müller

Constraints on cortical and thalamic projections: the no-strong-loops hypothesis

- Francis Crick

- Christof Koch

A tension-based theory of morphogenesis and compact wiring in the central nervous system

Many structural features of the mammalian central nervous system can be explained by a morphogenetic mechanism that involves mechanical tension along axons, dendrites and glial processes. In the cerebral cortex, for example, tension along axons in the white matter can explain how and why the cortex folds in a characteristic species-specific pattern. In the cerebellum, tension along parallel fibres can explain why the cortex is highly elongated but folded like an accordion. By keeping the aggregate length of axonal and dendritic wiring low, tension should contribute to the compactness of neural circuitry throughout the adult brain.

- David C. Van Essen

Implications of the late Palaeozoic oxygen pulse for physiology and evolution

- Jeffrey B. Graham

- Nancy M. Aguilar

Implications of the Copernican principle for our future prospects

Making only the assumption that you are a random intelligent observer, limits for the total longevity of our species of 0.2 million to 8 million years can be derived at the 95% confidence level. Further consideration indicates that we are unlikely to colonize the Galaxy, and that we are likely to have a higher population than the median for intelligent species.

- J. Richard Gott III

Polar path in geomagnetic reversals

- S. K. Runcorn

The extragalactic Universe: an alternative view

We discuss evidence to show that the generally accepted view of the Big Bang model for the origin of the Universe is unsatisfactory. We suggest an alternative model that satisfies the constraints better.

- G. Burbidge

- N. C. Wickramasinghe

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

What they need at the start of their research is to formulate a scientific hypothesis that revisits conventional theories, real-world processes, and related evidence to propose new studies and test ideas in an ethical way.3 Such a hypothesis can be of most benefit if published in an ethical journal with wide visibility and exposure to relevant ...

The hypothesis is a tentative prediction of the nature and direction of relationships between sets of data, phrased as a declarative statement. Therefore, hypotheses are really only required for studies that address relational or causal research questions. ... This article is the second in the CJHP Research Primer Series, an initiative of the ...

The main conclusion is therefore—given the proposed definitions of basic/general and applied research as well as the above-mentioned limitations of the present account—that (1) in basic/general hypothesis-testing research, a research hypothesis is sufficient, while a research problem is unjustified, and (2) in applied research, a research ...

Research hypothesis. The primary research question should be driven by the hypothesis rather than the data. 1, 2 That is, the research question and hypothesis should be developed before the start of the study. This sounds intuitive; however, if we take, for example, a database of information, it is potentially possible to perform multiple ...

Medical providers often rely on evidence-based medicine to guide decision-making in practice. Often a research hypothesis is tested with results provided, typically with p values, confidence intervals, or both. Additionally, statistical or research significance is estimated or determined by the investigators. Unfortunately, healthcare providers may have different comfort levels in interpreting ...

The first step in testing hypotheses is the transformation of the research question into a null hypothesis, H 0, and an alternative hypothesis, H A. 6 The null and alternative hypotheses are concise statements, usually in mathematical form, of 2 possible versions of "truth" about the relationship between the predictor of interest and the outcome in the population.

Browse and read free articles from APA Journals across the field of psychology, selected by the editors as the must-read content. ... Research, Practice, Consultation January 2017 by Monica M. Gerber, Jennifer L. Callahan, Danielle N. Moyer, Melissa L. Connally, Pamela M. Holtz, and Beth M. Janis ...

Abstract. The role of hypothesis testing, and especially of p-values, in evaluating the results of scientific experiments has been under debate for a long time.At least since the influential article by Ioannidis (Citation 2005) awareness is growing in the scientific community that the results of many research experiments are difficult or impossible to replicate.

1 Departments of Rheumatology and Research and Development, Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust (Teaching Trust of the University of Birmingham, UK), Russells Hall ... Reflecting on general and specific issues around the subject matter is often recommended for drafting a well-structured hypothesis article. An analysis of influential hypotheses ...

Browse the archive of articles on Nature. ... Hypothesis 20 Oct 2010. ... Research articles News Opinion ...