Michelangelo

Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo created the 'David' and 'Pieta' sculptures and the Sistine Chapel and 'Last Judgment' paintings.

(1475-1564)

Who Was Michelangelo?

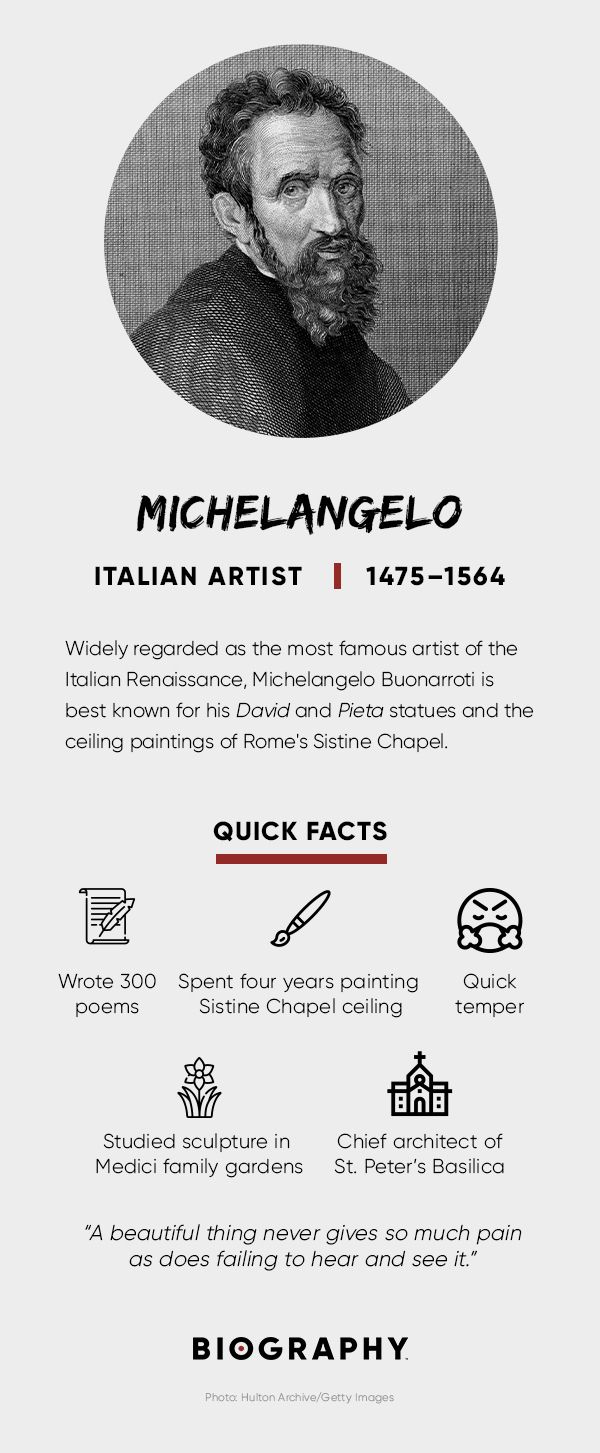

Michelangelo Buonarroti was a painter, sculptor, architect and poet widely considered one of the most brilliant artists of the Italian Renaissance . Michelangelo was an apprentice to a painter before studying in the sculpture gardens of the powerful Medici family .

What followed was a remarkable career as an artist, famed in his own time for his artistic virtuosity. Although he always considered himself a Florentine, Michelangelo lived most of his life in Rome, where he died at age 88.

Michelangelo was born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, Italy, the second of five sons.

When Michelangelo was born, his father, Leonardo di Buonarrota Simoni, was briefly serving as a magistrate in the small village of Caprese. The family returned to Florence when Michelangelo was still an infant.

His mother, Francesca Neri, was ill, so Michelangelo was placed with a family of stonecutters, where he later jested, "With my wet-nurse's milk, I sucked in the hammer and chisels I use for my statues."

Indeed, Michelangelo was less interested in schooling than watching the painters at nearby churches and drawing what he saw, according to his earliest biographers (Vasari, Condivi and Varchi). It may have been his grammar school friend, Francesco Granacci, six years his senior, who introduced Michelangelo to painter Domenico Ghirlandaio.

Michelangelo's father realized early on that his son had no interest in the family financial business, so he agreed to apprentice him, at the age of 13, to Ghirlandaio and the Florentine painter's fashionable workshop. There, Michelangelo was exposed to the technique of fresco (a mural painting technique where pigment is placed directly on fresh, or wet, lime plaster).

Medici Family

From 1489 to 1492, Michelangelo studied classical sculpture in the palace gardens of Florentine ruler Lorenzo de' Medici of the powerful Medici family. This extraordinary opportunity opened to him after spending only a year at Ghirlandaio’s workshop, at his mentor’s recommendation.

This was a fertile time for Michelangelo; his years with the family permitted him access to the social elite of Florence — allowing him to study under the respected sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni and exposing him to prominent poets, scholars and learned humanists.

He also obtained special permission from the Catholic Church to study cadavers for insight into anatomy, though exposure to corpses had an adverse effect on his health.

These combined influences laid the groundwork for what would become Michelangelo's distinctive style: a muscular precision and reality combined with an almost lyrical beauty. Two relief sculptures that survive, "Battle of the Centaurs" and "Madonna Seated on a Step," are testaments to his phenomenal talent at the tender age of 16.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S MICHELANGELO FACT CARD

Move to Rome

Political strife in the aftermath of Lorenzo de' Medici’s death led Michelangelo to flee to Bologna, where he continued his study. He returned to Florence in 1495 to begin work as a sculptor, modeling his style after masterpieces of classical antiquity.

There are several versions of an intriguing story about Michelangelo's famed "Cupid" sculpture, which was artificially "aged" to resemble a rare antique: One version claims that Michelangelo aged the statue to achieve a certain patina, and another version claims that his art dealer buried the sculpture (an "aging" method) before attempting to pass it off as an antique.

Cardinal Riario of San Giorgio bought the "Cupid" sculpture, believing it as such, and demanded his money back when he discovered he'd been duped. Strangely, in the end, Riario was so impressed with Michelangelo's work that he let the artist keep the money. The cardinal even invited the artist to Rome, where Michelangelo would live and work for the rest of his life.

Personality

Though Michelangelo's brilliant mind and copious talents earned him the regard and patronage of the wealthy and powerful men of Italy, he had his share of detractors.

He had a contentious personality and quick temper, which led to fractious relationships, often with his superiors. This not only got Michelangelo into trouble, it created a pervasive dissatisfaction for the painter, who constantly strived for perfection but was unable to compromise.

He sometimes fell into spells of melancholy, which were recorded in many of his literary works: "I am here in great distress and with great physical strain, and have no friends of any kind, nor do I want them; and I do not have enough time to eat as much as I need; my joy and my sorrow/my repose are these discomforts," he once wrote.

In his youth, Michelangelo had taunted a fellow student, and received a blow on the nose that disfigured him for life. Over the years, he suffered increasing infirmities from the rigors of his work; in one of his poems, he documented the tremendous physical strain that he endured by painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

Political strife in his beloved Florence also gnawed at him, but his most notable enmity was with fellow Florentine artist Leonardo da Vinci , who was more than 20 years his senior.

Poetry and Personal Life

Michelangelo's poetic impulse, which had been expressed in his sculptures, paintings and architecture, began taking literary form in his later years.

Although he never married, Michelangelo was devoted to a pious and noble widow named Vittoria Colonna, the subject and recipient of many of his more than 300 poems and sonnets. Their friendship remained a great solace to Michelangelo until Colonna's death in 1547.

Soon after Michelangelo's move to Rome in 1498, the cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas, a representative of the French King Charles VIII to the pope, commissioned "Pieta," a sculpture of Mary holding the dead Jesus across her lap.

Michelangelo, who was just 25 years old at the time, finished his work in less than one year, and the statue was erected in the church of the cardinal's tomb. At 6 feet wide and nearly as tall, the statue has been moved five times since, to its present place of prominence at St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City.

Carved from a single piece of Carrara marble, the fluidity of the fabric, positions of the subjects, and "movement" of the skin of the Piet — meaning "pity" or "compassion" — created awe for its early viewers, as it does even today.

It is the only work to bear Michelangelo’s name: Legend has it that he overheard pilgrims attribute the work to another sculptor, so he boldly carved his signature in the sash across Mary's chest. Today, the "Pieta" remains a universally revered work.

Between 1501 and 1504, Michelangelo took over a commission for a statue of "David," which two prior sculptors had previously attempted and abandoned, and turned the 17-foot piece of marble into a dominating figure.

The strength of the statue's sinews, vulnerability of its nakedness, humanity of expression and overall courage made the "David" a highly prized representative of the city of Florence.

Originally commissioned for the cathedral of Florence, the Florentine government instead installed the statue in front of the Palazzo Vecchio. It now lives in Florence’s Accademia Gallery .

Sistine Chapel

Pope Julius II asked Michelangelo to switch from sculpting to painting to decorate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, which the artist revealed on October 31, 1512. The project fueled Michelangelo’s imagination, and the original plan for 12 apostles morphed into more than 300 figures on the ceiling of the sacred space. (The work later had to be completely removed soon after due to an infectious fungus in the plaster, then recreated.)

Michelangelo fired all of his assistants, whom he deemed inept, and completed the 65-foot ceiling alone, spending endless hours on his back and guarding the project jealously until completion.

The resulting masterpiece is a transcendent example of High Renaissance art incorporating the symbology, prophecy and humanist principles of Christianity that Michelangelo had absorbed during his youth.

'Creation of Adam'

The vivid vignettes of Michelangelo's Sistine ceiling produce a kaleidoscope effect, with the most iconic image being the " Creation of Adam," a famous portrayal of God reaching down to touch the finger of man.

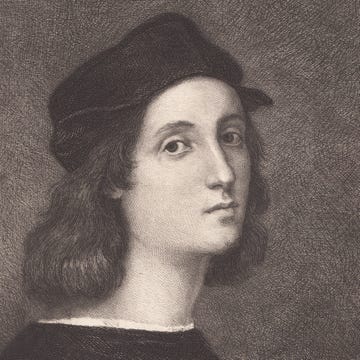

Rival Roman painter Raphael evidently altered his style after seeing the work.

'Last Judgment'

Michelangelo unveiled the soaring "Last Judgment" on the far wall of the Sistine Chapel in 1541. There was an immediate outcry that the nude figures were inappropriate for so holy a place, and a letter called for the destruction of the Renaissance's largest fresco.

The painter retaliated by inserting into the work new portrayals: his chief critic as a devil and himself as the flayed St. Bartholomew.

Architecture

Although Michelangelo continued to sculpt and paint throughout his life, following the physical rigor of painting the Sistine Chapel he turned his focus toward architecture.

He continued to work on the tomb of Julius II, which the pope had interrupted for his Sistine Chapel commission, for the next several decades. Michelangelo also designed the Medici Chapel and the Laurentian Library — located opposite the Basilica San Lorenzo in Florence — to house the Medici book collection. These buildings are considered a turning point in architectural history.

But Michelangelo's crowning glory in this field came when he was made chief architect of St. Peter's Basilica in 1546.

Was Michelangelo Gay?

In 1532, Michelangelo developed an attachment to a young nobleman, Tommaso dei Cavalieri, and wrote dozens of romantic sonnets dedicated to Cavalieri.

Despite this, scholars dispute whether this was a platonic or a homosexual relationship.

Michelangelo died on February 18, 1564 — just weeks before his 89th birthday — at his home in Macel de'Corvi, Rome, following a brief illness.

A nephew bore his body back to Florence, where he was revered by the public as the "father and master of all the arts." He was laid to rest at the Basilica di Santa Croce — his chosen place of burial.

Unlike many artists, Michelangelo achieved fame and wealth during his lifetime. He also had the peculiar distinction of living to see the publication of two biographies about his life, written by Giorgio Vasari and Ascanio Condivi.

Appreciation of Michelangelo's artistic mastery has endured for centuries, and his name has become synonymous with the finest humanist tradition of the Renaissance.

Watch "Michelangelo: Artist and Man" on HISTORY Vault

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Michelangelo Buonarroti

- Birth Year: 1475

- Birth date: March 6, 1475

- Birth City: Caprese (Republic of Florence)

- Birth Country: Italy

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo created the 'David' and 'Pieta' sculptures and the Sistine Chapel and 'Last Judgment' paintings.

- Fiction and Poetry

- Astrological Sign: Pisces

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Michelangelo was just 25 years old at the time when he created the 'Pieta' statue.

- For the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo fired all of his assistants and painted the 65-foot ceiling alone.

- Despite his immense talent, Michelangelo had a quick temper and contempt for authority.

- Death Year: 1564

- Death date: February 18, 1564

- Death City: Rome

- Death Country: Italy

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Michelangelo Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/artists/michelangelo

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: March 4, 2020

- Lord, grant that I may always desire more than I accomplish.

- I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.

- I am here in great distress and with great physical strain, and have no friends of any kind, nor do I want them; and I do not have enough time to eat as much as I need; my joy and my sorrow/my repose are these discomforts.

- With my wet-nurse's milk, I sucked in the hammer and chisels I use for my statues.

- A beautiful thing never gives so much pain as does failing to hear and see it.

- Faith in oneself is the best and safest course.

- If people knew how hard I worked to get my mastery, it wouldn't seem so wonderful at all.

- Critique by creating.

- The true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection.

- With few words I will make thee understand my soul.

- Lord, make me see thy glory in every place.

- Genius is eternal patience.

- If you knew how much work went into it, you wouldn't call it genius.

Famous Painters

Frida Kahlo

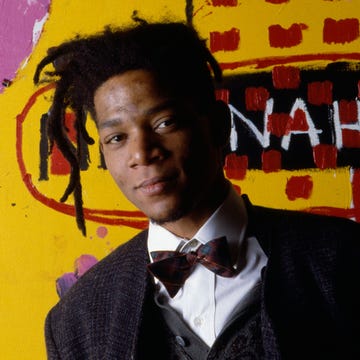

Jean-Michel Basquiat

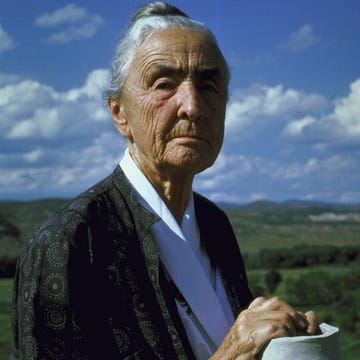

Georgia O'Keeffe

11 Notable Artists from the Harlem Renaissance

Fernando Botero

Gustav Klimt

The Surreal Romance of Salvador and Gala Dalí

Salvador Dalí

Michelangelo’s Life

How it works

‘’Your gifts lie in the place where your values, passions and strengths meet. Discovering that place is the first step toward sculpting your masterpiece, Your Life.’’- Michelangelo (1475–1564). Through these words, Michelangelo let us understand that is not easy to understand what you want to do in your life which mean that we have to work hard to discover our desires and passions, so we can create our art in life. Known as one of the uppermost Italian artists permanently and all over the world, Michelangelo gave birth to an era in the world of art and he reflected that perfectly the future world genius, Italian sculptor, artist and legislator of an era in world art and painting, one of the main masters of the Renaissance. Need a custom essay on the same topic? Give us your paper requirements, choose a writer and we’ll deliver the highest-quality essay! Order now

Moreover Michelangelo's excellent mind and abundant talents earned him the regard and patronage of the rich and influential men of Italy. A gladiatorial personality and fast temper, which led to irritable relationships, often with his superiors. Michelangelo’s life is reflected therefore in his power of Medici Family, his art work in Fresco Painting and Marble Statues, and his platonic association with Vittoria Colonna.

First of all, Michelangelo was someone who born to a family in banking business. Later on, he become part of “Medici family” where he studied classical sculpture. He was less fascinated in schooling than watching the artistes at nearby churches and drawing what he saw, rendering to his earliest biographers. The Medici family, also known as the House of Medici, first reached treasure and political power in Florence in the 13th century through its success in commerce and banking. With the rise to power, they backed the arts and humanities. More astonishing opportunity opened to Michelangelo after spending only a year at Ghirlandaio’s workshop. After that Michelangelo had access to the social elite of Florence which permitting him to study under the respected sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni and divulging him to prominent poets, scholars and learned humanists. These joint impacts laid the groundwork for what would become Michelangelo's unique style: a muscular precision and reality combined with an almost lyrical beauty. "Battle of the Centaurs" and "Madonna Seated on a Step," are proofs to his unrepeatable talent at the tender age of 16.

Secondly, Michelangelo’s artwork be made up in fresco painting, marble statues, and architecture that showed humanity in its natural state. By the time when Michelangelo was 30, he already had two marble statues “David” and “Pieta”. The two masterpiece which made him one of the greater artists of all the times. “Pieta” (1499) is a sculpture which signify Mary holding the dead Jesus across her lap. Just 25-years old at that time Michelangelo finished his work in less than one year and in nowadays “Pieta” (1499) leftovers an amazingly admired work. In 1504 another masterwork came out from Michelangelo which was “David” sculpture (1501-1504). A sculpture that took a lot of disapprovals from people because of the nakedness. However, the strength of the statue and courage made the "David" (1501-1504) a prized representative of the city of Florence. On the other hand, Michelangelo was very brilliant in fresco painting. The most famous one is: “Last Judgment” (1541) and “Sistine Chapel”. Practically all this fame comes from the spectacular paintings of its ceiling. Besides sculpting and painting he was amazing in architecture as well. Here we can mention “St. Peter’s Basilica” (1626) which is the most famous work of Renaissance architecture, is reckon as the greatest building of its age and remains one of the two giant churches in the world. He also created the “Medici Chapel” and the “Laurentian Library”. These structures are considered a crossroads in architectural history.

Thirdly, the last but not least Michelangelo has experienced platonic association with noble widow Vittoria Colonna whom he met in Rome in 1538. They exchanged about 300 letters and deep-thinking sonnets with each-other. Even though he was devoted to her, Michelangelo never married. When Vittoria died, Michelangelo was at her bedside. In his pitiful memorial sonnet, wrote that on her death “Nature that never made so fair a face, remained ashamed, and tears were in all eyes.” From that moment Michelangelo’s poetic impulse began taking literary form in his later years. Vittoria had a big influence on him regarding to the poetry. Occasionally he fell hooked on magic charm of melancholy, which were documented in many of his literary works. Once he wrote: "I am here in great distress and with great physical strain, and have no friends of any kind, nor do I want them; and I do not have enough time to eat as much as I need; my joy and my sorrow/my repose are these discomforts".

In conclusion, Michelangelo (1475-1564), the most potent force in the Italian High Renaissance, was possibly one of the most encouraged creators in the history of art. As a sculptor, architect, painter, and poet, he exerted a prodigious inspiration on today’s art. Michelangelo was revered by the public as the "father and master of all the arts."

Cite this page

Michelangelo’s life. (2019, Nov 01). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/michelangelos-life/

"Michelangelo’s life." PapersOwl.com , 1 Nov 2019, https://papersowl.com/examples/michelangelos-life/

PapersOwl.com. (2019). Michelangelo’s life . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/michelangelos-life/ [Accessed: 22 Nov. 2024]

"Michelangelo’s life." PapersOwl.com, Nov 01, 2019. Accessed November 22, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/michelangelos-life/

"Michelangelo’s life," PapersOwl.com , 01-Nov-2019. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/michelangelos-life/. [Accessed: 22-Nov-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2019). Michelangelo’s life . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/michelangelos-life/ [Accessed: 22-Nov-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

IMAGES

VIDEO