Essay on Government School

Students are often asked to write an essay on Government School in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Government School

Introduction.

Government schools are educational institutions funded by the state. They are important as they provide free or minimal cost education, ensuring everyone has access to learning.

Role and Importance

Government schools play a crucial role in society. They offer education to all, regardless of their economic status, promoting equality and social justice.

Despite their importance, government schools often face issues like lack of resources and poor infrastructure. However, they strive to overcome these obstacles and provide quality education.

In conclusion, government schools are pillars of our education system, crucial for fostering an educated and equal society.

250 Words Essay on Government School

The role of government schools.

Government schools, often referred to as public schools, play a crucial role in providing education to a wide demographic. These institutions, funded and managed by the government, ensure that quality education is accessible to all, irrespective of their socio-economic status.

Democratizing Education

Government schools democratize education by providing an opportunity for every child to learn and grow. They aim to bridge the gap between different socio-economic classes by offering free or low-cost education. This inclusivity is essential in fostering social harmony and reducing inequality.

Curriculum and Standards

The curriculum in government schools is designed to adhere to national education standards. This uniformity ensures that every child, regardless of their location or background, receives a similar standard of education. Moreover, it allows for a unified assessment system, making it easier to gauge and improve educational outcomes nationwide.

Challenges and Opportunities

Despite their pivotal role, government schools often face challenges such as inadequate funding, lack of resources, and understaffing. These issues can affect the quality of education. However, these challenges also present opportunities for reform. Innovative educational policies, increased investment, and community involvement can significantly improve the situation.

In conclusion, government schools are the backbone of an inclusive and egalitarian society. They ensure that every child has an equal opportunity to learn and succeed. Despite the challenges they face, with the right reforms and adequate support, government schools can continue to play a vital role in shaping the future of our nation.

500 Words Essay on Government School

Introduction to government schools.

Government schools, often referred to as public schools in many countries, are educational institutions primarily funded and maintained by the government. They are the backbone of the educational system in many developing and developed nations, providing free or low-cost education to millions of students who might otherwise lack access to quality learning opportunities.

Government schools play a crucial role in shaping a nation’s future. They are tasked with the responsibility of imparting education to all, regardless of socio-economic status, race, or religion. This principle of equality and inclusivity is a cornerstone of public education, ensuring that every child has an equal opportunity to learn and grow.

Government schools also serve as a platform for social interaction among diverse groups. They bring together children from different backgrounds, fostering a sense of unity, mutual respect, and understanding. This diversity is not just beneficial for students’ social development but also contributes to a more inclusive and accepting society.

Challenges Faced by Government Schools

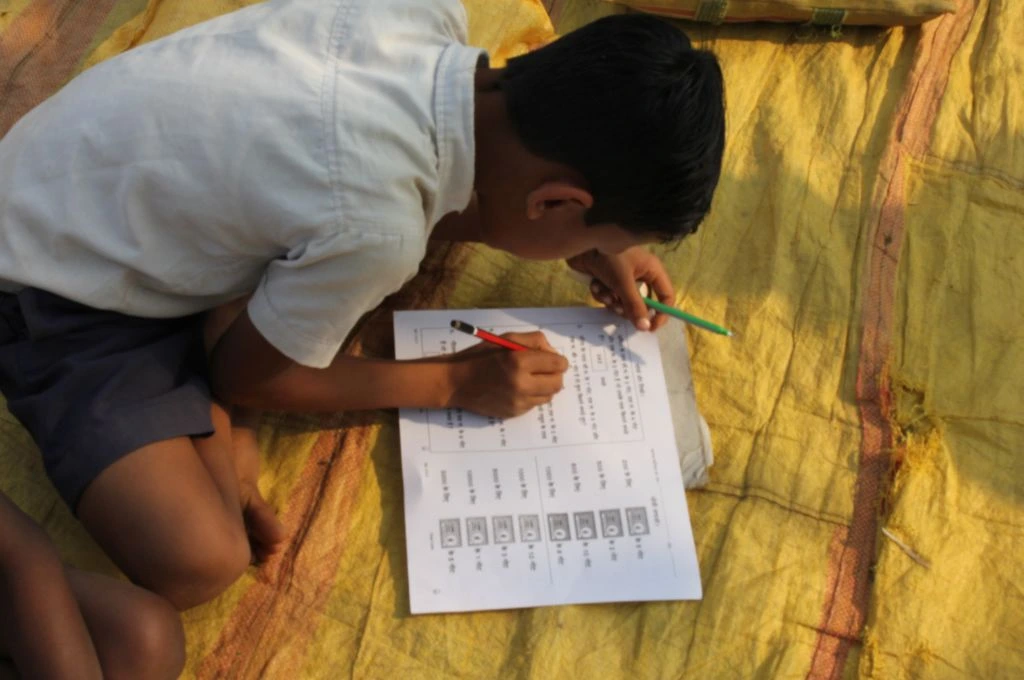

Despite their significant role, government schools often face numerous challenges. These include inadequate infrastructure, lack of qualified teachers, and insufficient resources. In many developing nations, government schools are plagued by issues such as overcrowded classrooms, poor sanitation facilities, and outdated teaching methods.

Furthermore, the quality of education in government schools is often a subject of concern. With limited resources, it can be challenging to provide personalized attention to each student or adopt innovative teaching methodologies. This often results in lower academic performance compared to private schools, leading to a perception that government schools offer inferior education.

Reforming Government Schools

Addressing these challenges requires comprehensive reforms. Governments need to invest more in public education, specifically in teacher training, infrastructure development, and curriculum enhancement. There is also a need for regular assessment and accountability to ensure that the quality of education is not compromised.

Moreover, innovative teaching methods, such as experiential learning and technology integration, can significantly improve the learning experience in government schools. Public-private partnerships can also be explored to bring additional resources and expertise to these schools.

Government schools are an integral part of a nation’s educational system. They provide opportunities for quality education to all, fostering social equality and inclusivity. Despite the challenges they face, with the right reforms and investments, government schools have the potential to offer a robust and comprehensive education to all students. They can serve as a powerful tool in shaping a nation’s future, contributing to social, economic, and political development.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Manners Make the Man

- Essay on Good Manners

- Essay on Good Handwriting

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

My Study Times

Education through Innovation

Government Schools vs Private Schools Essay , Debate, Speech

Government Schools vs Private Schools Essay , Debate, Speech | Advantages of Private Schools | DisAdvantages of Private Schools | Advantages of Government Schools | Disadvantages of Government Schools | Government Schools vs Private Schools Debate

Schools are the temples of knowledge and it is the place where a student grows up to be a scholar. Education is the backbone of development of a country and therefore developing this sector is always a part of great consideration by the government. However the question is that which of the two schools are better: Government or Private?

For a few students, either of the choice of school does not matter. They progress under any supervision. But in reality, differences do exist if we compare the two types of schools.

Government Schools vs Private Schools Essay

Let us talk about the Government school first. Government schools are a hope for the underprivileged sector of the society. It is those Government schools only which are within their limited capacity and affordability. Government schools provides free and compulsory education to children up to the age of 14 years which is not under the consideration by any private institution. Government schools are setup to provide only minimum required infrastructure and quality of education. This is an important drawback of Government schools. There is no regulation of batch sizes in most of the government institutions. So, many times students suffer as a teacher finds it difficult to control a classroom or give enough attention to weaker students within a stipulated time.

Government Schools vs Private Schools Advantages – Disadvantages

Coming to the discussion of Private schools, In many ways it is wiser to enroll oneself in a Private institution as it has got some serious advantages over Government Schools . Private schools are better in approach towards psychological development of a child. Also better infrastructure is provided by them. Education in Private schools are slowly shifting into Audio- visual mode, which makes studies and learning a fun experience. While the Government schools do not take much steps in improving the quality of performance of the faculties. Many teachers just join for the good- looking salaries but do not care about their teaching and class. Also, in Private schools there are people to check how each teacher is conducting his/her classes as there must be some compulsory tests or evaluation taken each week/ month to check on the progress of a student. These ensure that the teachers are involved too. Quality of Laboratories and Sports education is a lot better in Private school. Ina Private school only a student gets the scope to learn the civilized and modern approach which is in demand in MNC culture.

Conclusion of Government Schools vs Private Schools Debate

Therefore, We can conclude that while Government institutions focus only on basic education, Private schools on other hand believe in providing better opportunities to its students as they face a competition from fellow Private schools as well.

Government Schools vs Private Schools Essay , Debate, Speech , Advantages of Private Schools , DisAdvantages of Private Schools , Advantages of Government Schools , Disadvantages of Government Schools , Government Schools vs Private Schools Debate

About Charmin Patel

Blogger and Digital Marketer by Choice and Chemical Engineer By Chance. Computer and Internet Geek Person Who Loves To Do Something New Every Day.

- Education Savings Accounts

- School Vouchers

- Tax-Credit ESAs

- Tax-Credit Scholarships

- Individual Tax Credits and Deductions

- School Choice in America

- Research Library – main

- Schooling in America Survey Dashboard

- Public Opinion Tracker

- Project Nickel

- School Choice Bibliography

- EdChoice Experts

- Connecticut

- Massachusetts

- Mississippi

- New Hampshire

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- West Virginia

- Washington, D.C.

- Puerto Rico

- U.S. Virgin Islands

- Northern Mariana Islands

- American Samoa

The Role of Government in Education

From Milton Friedman (1962/1982), Capitalism and Freedom (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press); earlier version (1955) in Robert A. Solo (Ed.), Economics and the Public Interest , pp. 123-144 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press).

The general trend in our times toward increasing intervention by the state in economic affairs has led to a concentration of attention and dispute on the areas where new intervention is proposed and to an acceptance of whatever intervention has so far occurred as natural and unchangeable. The current pause, perhaps reversal, in the trend toward collectivism offers an opportunity to re-examine the existing activities of government and to make a fresh assessment of the activities that are and those that are not justified. This paper attempts such a re-examination for education.

Education is today largely paid for and almost entirely administered by governmental bodies or non-profit institutions. This situation has developed gradually and is now taken so much for granted that little explicit attention is any longer directed to the reasons for the special treatment of education even in countries that are predominantly free enterprise in organization and philosophy. The result has been an indiscriminate extension of governmental responsibility.

The role assigned to government in any particular field depends, of course, on the principles accepted for the organization of society in general. In what follows, I shall assume a society that takes freedom of the individual, or more realistically the family, as its ultimate objective, and seeks to further this objective by relying primarily on voluntary exchange among individuals for the organization of economic activity. In such a free private enterprise exchange economy, government’s primary role is to preserve the rules of the game by enforcing contracts, preventing coercion, and keeping markets free. Beyond this, there are only three major grounds on which government intervention is to be justified. One is “natural monopoly” or similar market imperfection which makes effective competition (and therefore thoroughly voluntary exchange) impossible. A second is the existence of substantial “neighborhood effects,” i.e., the action of one individual imposes significant costs on other individuals for which it is not feasible to make him compensate them or yields significant gains to them for which it is not feasible to make them compensate him — circumstances that again make voluntary exchange impossible. The third derives from an ambiguity in the ultimate objective rather than from the difficulty of achieving it by voluntary exchange, namely, paternalistic concern for children and other irresponsible individuals. The belief in freedom is for “responsible” units, among whom we include neither children nor insane people. In general, this problem is avoided by regarding the family as the basic unit and therefore parents as responsible for their children; in considerable measure, however, such a procedure rests on expediency rather than principle. The problem of drawing a reasonable line between action justified on these paternalistic grounds and action that conflicts with the freedom of responsible individuals is clearly one to which no satisfactory answer can be given.

In applying these general principles to education, we shall find it helpful to deal separately with (1) general education for citizenship, and (2) specialized vocational education, although it may be difficult to draw a sharp line between them in practice. The grounds for government intervention are widely different in these two areas and justify very different types of action.

General Education for Citizenship

A stable and democratic society is impossible without widespread acceptance of some common set of values and without a minimum degree of literacy and knowledge on the part of most citizens. Education contributes to both. In consequence, the gain from the education of a child accrues not only to the child or to his parents but to other members of the society; the education of my child contributes to other people’s welfare by promoting a stable and democratic society. Yet it is not feasible to identify the particular individuals (or families) benefited or the money value of the benefit and so to charge for the services rendered. There is therefore a significant “neighborhood effect.”

What kind of governmental action is justified by this particular neighborhood effect? The most obvious is to require that each child receive a minimum amount of education of a specified kind. Such a requirement could be imposed upon the parents without further government action, just as owners of buildings, and frequently of automobiles, are required to adhere to specified standards to protect the safety of others. There is, however, a difference between the two cases. In the latter, individuals who cannot pay the costs of meeting the required standards can generally divest themselves of the property in question by selling it to others who can, so the requirement can readily be enforced without government subsidy — though even here, if the cost of making the property safe exceeds its market value, and the owner is without resources, the government may be driven to paying for the demolition of a dangerous building or the disposal of an abandoned automobile. The separation of a child from a parent who cannot pay for the minimum required education is clearly inconsistent with our reliance on the family as the basic social unit and our belief in the freedom of the individual.

Yet, even so, if the financial burden imposed by such an educational requirement could readily be met by the great bulk of the families in a community, it might be both feasible and desirable to require the parents to meet the cost directly.

Extreme cases could be handled by special provisions in much the same way as is done now for housing and automobiles. An even closer analogy is provided by present arrangements for children who are mistreated by their parents. The advantage of imposing the costs on the parents is that it would tend to equalize the social and private costs of having children and so promote a better distribution of families by size. 1

Differences among families in resources and in number of children — both a reason for and a result of the different policy that has been followed — plus the imposition of a standard of education involving very sizable costs have, however, made such a policy hardly feasible. Instead, government has assumed the financial costs of providing the education. In doing so, it has paid not only for the minimum amount of education required of all but also for additional education at higher levels available to youngsters but not required of them — as for example in State and municipal colleges and universities. Both steps can be justified by the “neighborhood effect” discussed above — the payment of the costs as the only feasible means of enforcing the required minimum; and the financing of additional education, on the grounds that other people benefit from the education of those of greater ability and interest since this is a way of providing better social and political leadership.

Government subsidy of only certain kinds of education can be justified on these grounds. To anticipate, they do not justify subsidizing purely vocational education which increases the economic productivity of the student but does not train him for either citizenship or leadership. It is clearly extremely difficult to draw a sharp line between these two types of education. Most general education adds to the economic value of the student — indeed it is only in modern times and in a few countries that literacy has ceased to have a marketable value. And much vocational education broadens the student’s outlook. Yet it is equally clear that the distinction is a meaningful one. For example, subsidizing the training of veterinarians, beauticians, dentists, and a host of other specialized skills — as is widely done in the United States in governmentally supported educational institutions — cannot be justified on the same grounds as subsidizing elementary education or, at a higher level, liberal education. Whether it can be justified on quite different grounds is a question that will be discussed later in this paper.

The qualitative argument from the “neighborhood effect” does not, of course, determine the specific kids of education that should be subsidized or by how much they should be subsidized. The social gain from education is presumably greatest for the very lowest levels of education, where there is the nearest approach to unanimity about the content of the education, and declines continuously as the level of education rises. But even this statement cannot be taken completely for granted — many governments subsidized universities long before they subsidized lower education. What forms of education have the greatest social advantage and how much of the community’s limited resources should be spent on them are questions to be decided by the judgment of the community expressed through its accepted political channels. The role of an economist is not to decide these questions for the community but rather to clarify the issues to be judged by the community in making a choice, in particular, whether the choice is one that it is appropriate or necessary to make on a communal rather than individual basis.

We have seen that both the imposition of a minimum required level of education and the financing of education by the state can be justified by the “neighborhood effects” of education. It is more difficult to justify in these terms a third step that has generally been taken, namely, the actual administration of educational institutions by the government, the “nationalization,” as it were, of the bulk of the “education industry.” The desirability of such nationalization has seldom been faced explicitly because governments have in the main financed education by paying directly the costs of running educational institutions, so that this step has seemed required by the decision to subsidize education. Yet the two steps could readily be separated. Governments could require a minimum level of education which they could finance by giving parents vouchers redeemable for a specified maximum sum per child per year if spent on “approved” educational services.

Parents would then be free to spend this sum and any additional sum on purchasing educational services from an “approved” institution of their own choice. The educational services could be rendered by private enterprises operated for profit, or by non-profit institutions of various kinds. The role of the government would be limited to assuring that the schools met certain minimum standards such as the inclusion of a minimum common content in their programs, much as it now inspects restaurants to assure that they maintain minimum sanitary standards. An excellent example of a program of this sort is the United States educational program for veterans after World War II. Each veteran who qualified was given a maximum sum per year that could be spent at any institution of his choice, provided it met certain minimum standards. A more limited example is the provision in Britain whereby local authorities pay the fees of some students attending nonstate schools (the so-called “public schools”). Another is the arrangement in France whereby the state pays part of the costs for students attending non-state schools.

One argument from the “neighborhood effect” for nationalizing education is that it might otherwise be impossible to provide the common core of values deemed requisite for social stability. The imposition of minimum standards on privately conducted schools, as suggested above, might not be enough to achieve this result. The issue can be illustrated concretely in terms of schools run by religious groups. Schools run by different religious groups will, it can be argued, instill sets of values that are inconsistent with one another and with those instilled in other schools; in this way they convert education into a divisive rather than a unifying force.

Carried to its extreme, this argument would call not only for governmentally administered schools, but also for compulsory attendance at such schools. Existing arrangements in the United States and most other Western countries are a halfway house. Governmentally administered schools are available but not required. However, the link between the financing of education and its administration places other schools at a disadvantage: they get the benefit of little or none of the governmental funds spent on education — a situation that has been the source of much political dispute, particularly, of course, in France. The elimination of this disadvantage might, it is feared, greatly strengthen the parochial schools and so render the problem of achieving a common core of values even more difficult.

This argument has considerable force. But it is by no means clear either that it is valid or that the denationalizing of education would have the effects suggested. On grounds of principle, it conflicts with the preservation of freedom itself; indeed, this conflict was a major factor retarding the development of state education in England. How draw a line between providing for the common social values required for a stable society on the one hand, and indoctrination inhibiting freedom of thought and belief on the other? Here is another of those vague boundaries that it is easier to mention than to define.

In terms of effects, the denationalization of education would widen the range of choice available to parents. Given, as at present, that parents can send their children to government schools without special payment, very few can or will send them to other schools unless they too are subsidized.

Parochial schools are at a disadvantage in not getting any of the public funds devoted to education; but they have the compensating advantage of being funded by institutions that are willing to subsidize them and can raise funds to do so, whereas there are few other sources of subsidies for schools.

Let the subsidy be made available to parents regardless where they send their children — provided only that it be to schools that satisfy specified minimum standards — and a wide variety of schools will spring up to meet the demand. Parents could express their views about schools directly, by withdrawing their children from one school and sending them to another, to a much greater extent than is now possible. In general, they can now take this step only by simultaneously changing their place of residence.

For the rest, they can express their views only through cumbrous political channels. Perhaps a somewhat greater degree of freedom to choose schools could be made available also in a governmentally administered system, but it is hard to see how it could be carried very far in view of the obligation to provide every child with a place. Here, as in other fields, competitive private enterprise is likely to be far more efficient in meeting consumer demands than either nationalized enterprises or enterprises run to serve other purposes. The final result may therefore well be less rather than more parochial education.

Another special case of the argument that governmentally conducted schools are necessary to keep education a unifying force is that private schools would tend to exacerbate class distinctions. Given greater freedom about where to send their children, parents of a kind would flock together and so prevent a healthy intermingling of children from decidedly different backgrounds. Again, whether or not this argument is valid in principle, it is not at all clear that the stated results would follow. Under present arrangements, particular schools tend to be peopled by children with similar backgrounds thanks to the stratification of residential areas. In addition, parents are not now prevented from sending their children to private schools. Only a highly limited class can or does do so, parochial schools aside, in the process producing further stratification. The widening of the range of choice under a private system would operate to reduce both kinds of stratification.

Another argument for nationalizing education is “natural monopoly.” In small communities and rural areas, the number of children may be too small to justify more than one school of reasonable size, so that competition cannot be relied on to protect the interests of parents and children. As in other cases of natural monopoly, the alternatives are unrestricted private monopoly, state-controlled private monopoly, and public operation — a choice among evils. This argument is clearly valid and significant, although its force has been greatly weakened in recent decades by improvements in transportation and increasing concentration of the population in urban communities.

The arrangement that perhaps comes closest to being justified by these considerations — at least for primary and secondary education — is a mixed one under which governments would continue to administer some schools but parents who chose to send their children to other schools would be paid a sum equal to the estimated cost of educating a child in a government school, provided that at least this sum was spent on education in an approved school. This arrangement would meet the valid features of the “natural monopoly” argument, while at the same time it would permit competition to develop where it could. It would meet the just complaints of parents that if they send their children to private nonsubsidized schools they are required to pay twice for education — once in the form of general taxes and once directly — and in this way stimulate the development and improvement of such schools. The interjection of competition would do much to promote a healthy variety of schools. It would do much, also, to introduce flexibility into school systems. Not least of its benefits would be to make the salaries of school teachers responsive to market forces. It would thereby give governmental educational authorities an independent standard against which to judge salary scales and promote a more rapid adjustment to changes in conditions of demand or supply. 2

Why is it that our educational system has not developed along these lines? A full answer would require a much more detailed knowledge of educational history than I possess, and the most I can do is to offer a conjecture. For one thing, the “natural monopoly” argument was much stronger at an earlier date. But I suspect that a much more important factor was the combination of the general disrepute of cash grants to individuals (“handouts”) with the absence of an efficient administrative machinery to handle the distribution of vouchers and to check their use. The development of such machinery is a phenomenon of modern times that has come to full flower only with the enormous extension of personal taxation and of social security programs. In its absence, the administration of schools was regarded as the only possible way to finance education. Of course, as some of the examples cited above suggest, some features of the proposed arrangements are present in existing educational systems. And there has been strong and I believe increasing pressure for arrangements of this general kind in most Western countries, which is perhaps to be explained by the modern developments in governmental administrative machinery that facilitate such arrangements.

Many detailed administrative problems would arise in changing over from the present to the proposed system and in administering the proposed system. But these seem neither insoluble nor unique. As in the denationalization of other activities, existing premises and equipment could be sold to private enterprises that wanted to enter the field, so there would be no waste of capital in the transition. The fact that governmental units, at least in some areas, were going to continue to administer schools would permit a gradual and easy transition. The localized administration of education in the United States and some other countries would similarly facilitate the transition, since it would encourage experimentation on a small scale and with alternative methods of handling both these and other problems.

Difficulties would doubtless arise in determining eligibility for grants from a particular governmental unit, but this is identical with the existing problem of determining which unit is obligated to provide educational facilities for a particular child. Differences in size of grants would make one area more attractive than another just as differences in the quality of education now have the same effect.

The only additional complication is a possibly greater opportunity for abuse because of the greater freedom to decide where to educate children. Supposed difficulty of administration is a standard defense of the status quo against any proposed changes; in this particular case, it is an even weaker defense than usual because existing arrangements must master not only the major problems raised by the proposed arrangements but also the additional problems raised by the administration of the schools as a governmental function.

The preceding discussion is concerned mostly with primary and secondary education. For higher education, the case for nationalization on grounds either of neighborhood effects or of natural monopoly is even weaker than for primary and secondary education. For the lowest levels of education, there is considerable agreement, approximating unanimity, on the appropriate content of an educational program for citizens of a democracy — the three R’s cover most of the ground. At successively higher levels of education, there is less and less agreement. Surely, well below the level of the American college, one can expect insufficient agreement to justify imposing the views of a majority, much less a plurality, on all. The lack of agreement may, indeed, extend so far as to cast doubts on the appropriateness of even subsidizing education at this level; it surely goes far enough to undermine any case for nationalization on the grounds of providing a common core of values. Similarly, there can hardly be any question of “natural monopoly” at this level, in view of the distances that individuals can and do go to attend institutions of higher learning.

Governmental institutions in fact play a smaller role in the United States in higher education than at lower levels. Yet they grew greatly in importance until at least the 1920’s and now account for more than half the students attending colleges and universities. 3 One of the main reasons for their growth was their relative cheapness: most State and municipal colleges and universities charge much lower tuition fees than private universities can afford to. Private universities have in consequence had serious financial problems, and have quite properly complained of “unfair” competition. They have wanted to maintain their independence from government, yet at the same time have felt driven by financial pressure to seek government aid.

The preceding analysis suggests the lines along which a satisfactory solution can be found. Public expenditure on higher education can be justified as a means of training youngsters for citizenship and for community leadership — though I hasten to add that the large fraction of current expenditure that goes for strictly vocational training cannot be justified in this way or, indeed, as we shall see, in any other. Restricting the subsidy to education obtained at a state-administered institution cannot be justified on these grounds, or on any other that I can derive from the basic principles outlined at the outset. Any subsidy should be granted to individuals to be spent at institutions of their own choosing, provided only that the education is of a kind that it is desired to subsidize. Any government schools that are retained should charge fees covering the cost of educating students and so compete on an equal level with non-government-supported schools. The retention of state schools themselves would, however, have to be justified on grounds other than those we have so far considered. 4 The resulting system would follow in its broad outlines the arrangements adopted in the United States after World War II for financing the education of veterans, except that the funds would presumably come from the States rather than the Federal government.

The adoption of such arrangements would make for more effective competition among various types of schools and for a more efficient utilization of their resources. It would eliminate the pressure for direct government assistance to private colleges and universities and thus preserve their full independence and diversity at the same time that it enabled them to grow relatively to State institutions. It might also have the ancillary advantage of causing a closer scrutiny of the purposes for which subsidies are granted. The subsidization of institutions rather than of people has led to an indiscriminate subsidization of whatever activities it is appropriate for such institutions to undertake, rather than of the activities it is appropriate for the state to subsidize. Even cursory examination suggests that while the two classes of activities overlap, they are far from identical.

Vocational or Professional Education

As noted above, vocational or professional education has no neighborhood effects of the kind attributed above to general education. It is a form of investment in human capital precisely analogous to investment in machinery, buildings, or other forms of nonhuman capital. Its function is to raise the economic productivity of the human being. If it does so, the individual is rewarded in a free enterprise society by receiving a higher return for his services than he would otherwise be able to command. 5 This difference is the economic incentive to acquire the specialized training, just as the extra return that can be obtained with an extra machine is the economic incentive to invest capital in the machine. In both cases, extra returns must be balanced against the costs of acquiring them. For vocational education, the major costs are the income foregone during the period of training, interest lost by postponing the beginning of the earning period, and special expenses of acquiring the training such as tuition fees and expenditures on books and equipment. For physical capital, the major costs are the expenses of constructing the capital equipment and the interest during construction.

In both cases, an individual presumably regards the investment as desirable if the extra returns, as he views them, exceed the extra costs, as he views them. 6 In both cases, if the individual undertakes the investment and if the state neither subsidizes the investment nor taxes the return, the individual (or his parent, sponsor, or benefactor) in general bears all the extra cost and receives all the extra returns: there are no obvious unborne costs or unappropriable returns that tend to make private incentives diverge systematically from those that are socially appropriate. If capital were as readily available for investment in human beings as for investment in physical assets, whether through the market or through direct investment by the individuals concerned or their parents or benefactors, the rate of return on capital would tend to be roughly equal in the two fields: if it were higher on non-human capital, parents would have an incentive to buy such capital for their children instead of investing a corresponding sum in vocational training, and conversely. In fact, however, there is considerable empirical evidence that the rate of return on investment in training is very much higher than the rate of return on investment in physical capital.

According to estimates that Simon Kuznets and I have made elsewhere, professionally trained workers in the United States would have had to earn during the 1930s at most 70 percent more than other workers to cover the extra costs of their training, including interest at roughly the market rate on non-human capital. In fact, they earned on the average between two and three times as much. 7

Some part of this difference may well be attributable to greater natural ability on the part of those who entered the professions: it may be that they would have earned more than the average non-professional worker if they had not gone into the professions. Kuznets and I concluded, however, that such differences in ability could not explain anything like the whole of the extra return of the professional workers. 8 Apparently, there was sizable underinvestment in human beings. The postwar period has doubtless brought changes in the relative earnings in different occupations.

It seems extremely doubtful, however, that they have been sufficiently great to reverse this conclusion. It is not certain at what level this underinvestment sets in. It clearly applies to professions requiring a long period of training, such as medicine, law, dentistry, and the like and probably to all occupations requiring a college training. At one time, it almost certainly extended to many occupations requiring much less training but probably no longer does, although the opposite has sometimes been maintained. 9

This underinvestment in human capital presumably reflects an imperfection in the capital market: investment in human beings cannot be financed on the same terms or with the same ease as investment in physical capital. It is easy to see why there would be such a difference. If a fixed money loan is made to finance investment in physical capital, the lender can get some security for his loan in the form of a mortgage or residual claim to the physical asset itself, and he can count on realizing at least part of his investment in case of necessity by selling the physical asset. If he makes a comparable loan to increase the earning power of a human being, he clearly cannot get any comparable security; in a non-slave state, the individual embodying the investment cannot be bought and sold. But even if he could, the security would not be comparable. The productivity of the physical capital does not — or at least generally does not — depend on the co-operativeness of the original borrower. The productivity of the human capital quite obviously does — which is, of course, why, all ethical considerations aside, slavery is economically inefficient. A loan to finance the training of an individual who has no security to offer other than his future earnings is therefore a much less attractive proposition than a loan to finance, say, the erection of a building: the security is less, and the cost of subsequent collection of interest and principal is very much greater.

A further complication is introduced by the inappropriateness of fixed money loans to finance investment in training. Such an investment necessarily involves much risk. The average expected return may be high, but there is wide variation about the average. Death or physical incapacity is one obvious source of variation but is probably much less important than differences in ability, energy, and good fortune. The result is that if fixed money loans were made, and were secured only by expected future earnings, a considerable fraction would never be repaid. In order to make such loans attractive to lenders, the nominal interest rate charged on all loans would have to be sufficiently high to compensate for the capital losses on the defaulted loans. The high nominal interest rate would both conflict with usury laws and make the loans unattractive to borrowers, especially to borrowers who have or expect to have other assets on which they cannot currently borrow but which they might have to realize or dispose of to pay the interest and principal of the loan. 10 The device adopted to meet the corresponding problem for other risky investments is equity investment plus limited liability on the part of shareholders. The counterpart for education would be to “buy” a share in an individual’s earning prospects: to advance him the funds needed to finance his training on condition that he agree to pay the lender a specified fraction of his future earnings. In this way, a lender would get back more than his initial investment from relatively successful individuals, which would compensate for the failure to recoup his original investment from the unsuccessful.

There seems no legal obstacle to private contracts of this kind, even though they are economically equivalent to the purchase of a share in an individual’s earning capacity and thus to partial slavery. One reason why such contracts have not become common, despite their potential profitability to both lenders and borrowers, is presumably the high costs of administering them, given the freedom of individuals to move from one place to another, the need for getting accurate income statements, and the long period over which the contracts would run. These costs would presumably be particularly high for investment on a small scale with a resultant wide geographical spread of the individuals financed in this way. Such costs may well be the primary reason why this type of investment has never developed under private auspices. But I have never been able to persuade myself that a major role has not also been played by the cumulative effect of such factors as the novelty of the idea, the reluctance to think of investment in human beings as strictly comparable to investment in physical assets, the resultant likelihood of irrational public condemnation of such contracts, even if voluntarily entered into, and legal and conventional limitation on the kind of investments that may be made by the financial intermediaries that would be best suited to engage in such investments, namely, life insurance companies. The potential gains, particularly to early entrants, are so great that it would be worth incurring extremely heavy administrative costs. 11

But whatever the reason, there is clearly here an imperfection of the market that has led to underinvestment in human capital and that justifies government intervention on grounds both of “natural monopoly,” insofar as the obstacle to the development of such investment has been administrative costs, and of improving the operation of the market, insofar as it has been simply market frictions and rigidities.

What form should government intervention take? One obvious form, and the only form that it has so far taken, is outright government subsidy of vocational or professional education financed out of general revenues. Yet this form seems clearly inappropriate. Investment should be carried to the point at which the extra return repays the investment and yields the market rate of interest on it. If the investment is in a human being, the extra return takes the form of a higher payment for the individual’s services than he could otherwise command. In a private market economy, the individual would get this return as his personal income, yet if the investment were subsidized, he would have borne none of the costs. In consequence, if subsidies were given to all who wished to get the training, and could meet minimum quality standards, there would tend to be overinvestment in human beings, for individuals would have an incentive to get the training so long as it yielded any extra return over private costs, even if the return were insufficient to repay the capital invested, let alone yield any interest on it. To avoid such overinvestment, government would have to restrict the subsidies. Even apart from the difficulty of calculating the “correct” amount of investment, this would involve rationing in some essentially arbitrary way the limited amount of investment among more claimants than could be financed, and would mean that those fortunate enough to get their training subsidized would receive all the returns from the investment whereas the costs would be borne by the taxpayers in general. This seems an entirely arbitrary, if not perverse, redistribution of income.

The desideratum is not to redistribute income but to make capital available for investment in human beings on terms comparable to those on which it is available for physical investment. Individuals should bear the costs of investment in themselves and receive the rewards, and they should not be prevented by market imperfections from making the investment when they are willing to bear the costs. One way to do this is to have government engage in equity investment in human beings of the kind described above.

A governmental body could offer to finance or help finance the training of any individual who could meet minimum quality standards by making available not more than a limited sum per year for not more than a specified number of years, provided it was spent on securing training at a recognized institution. The individual would agree in return to pay to the government in each future year x percent of his earnings in excess of y dollars for each $1,000 that he gets in this way. This payment could easily be combined with payment of income tax and so involve a minimum of additional administrative expense. The base sum, $y, should be set equal to estimated average — or perhaps modal — earnings without the specialized training; the fraction of earnings paid, x , should be calculated so as to make the whole project self-financing. In this way the individuals who received the training would in effect bear the whole cost. The amount invested could then be left to be determined by individual choice. Provided this was the only way in which government financed vocational or professional training, and provided the calculated earnings reflected all relevant returns and costs, the free choice of individuals would tend to produce the optimum amount of investment. The second proviso is unfortunately not likely to be fully satisfied. In practice, therefore, investment under the plan would still be somewhat too small and would not be distributed in the optimum manner. To illustrate the point at issue, suppose that a particular skill acquired by education can be used in two different ways; for example, medical skill in research or in private practice. Suppose that, if money earnings were the same, individuals would generally prefer research. The non-pecuniary advantages of research would then tend to be offset by higher money earnings in private practice. These higher earnings would be included in the sum to which the fraction x was applied whereas the monetary equivalent of the non-pecuniary advantages of research would not be. In consequence, the earnings differential would have to be higher under the plan than if individuals could finance themselves, since it is the net monetary differential, not the gross, that individuals would balance against the non-pecuniary advantages of research in deciding how to use their skill. This result would be produced by a larger than optimum fraction of individuals going into research necessitating a higher value of x to make the scheme self-financing than if the value of the non-pecuniary advantages could be included in calculated earnings. The inappropriate use of human capital financed under the plan would in this way lead to a less than optimum incentive to invest and so to a less than optimum amount of investment. 12

Estimation of the values of x and y clearly offers considerable difficulties, especially in the early years of operation of the plan, and the danger would always be present that they would become political footballs. Information on existing earnings in various occupations is relevant but would hardly permit anything more than a rough approximation to the values that would render the project self-financing. In addition, the values should in principle vary from individual to individual in accordance with any differences in expected earning capacity that can be predicted in advance — the problem is similar to that of varying life insurance premia among groups that have different life expectancy. For such reasons as these it would be preferable if similar arrangements could be developed on a private basis by financial institutions in search of outlets for investing their funds, non-profit institutions such as private foundations, or individual universities and colleges.

Insofar as administrative expense is the obstacle to the development of such arrangements on a private basis, the appropriate unit of government to make funds available is the Federal government in the United States rather than smaller units. Any one State would have the same costs as an insurance company, say, in keeping track of the people whom it had financed. These would be minimized for the Federal government. Even so, they would not be completely eliminated. An individual who migrated to another country, for example, might still be legally or morally obligated to pay the agreed-on share of his earnings, yet it might be difficult and expensive to enforce the obligation. Highly successful people might therefore have an incentive to migrate. A similar problem arises, of course, also under the income tax, and to a very much greater extent. This and other administrative problems of conducting the scheme on a Federal level, while doubtless troublesome in detail, do not seem serious. The really serious problem is the political one already mentioned: how to prevent the scheme from becoming a political football and in the process being converted from a self-financing project to a means of subsidizing vocational education.

But if the danger is real, so is the opportunity. Existing imperfections in the capital market tend to restrict the more expensive vocational and professional training to individuals whose parents or benefactors can finance the training required. They make such individuals a “non-competing” group sheltered from competition by the unavailability of the necessary capital to many individuals, among whom must be large numbers with equal ability. The result is to perpetuate inequalities in wealth and status. The development of arrangements such as those outlined above would make capital more widely available and would thereby do much to make equality of opportunity a reality, to “diminish inequalities of income and wealth, and to promote the full use of our human resources. And it would do so not, like the outright redistribution of income, by impeding competition, destroying incentive, and dealing with symptoms, but by strengthening competition, making incentives effective, and eliminating the causes of inequality.

This re-examination of the role of government in education suggests that the growth of governmental responsibility in this area has been unbalanced. Government has appropriately financed general education for citizenship, but in the process it has been led also to administer most of the schools that provide such education. Yet, as we have seen, the administration of schools is neither required by the financing of education, nor justifiable in its own right in a predominantly free enterprise society. Government has appropriately been concerned with widening the opportunity of young men and women to get professional and technical training, but it has sought to further this objective by the inappropriate means of subsidizing such education, largely in the form of making it available free or at a low price at governmentally operated schools.

The lack of balance in governmental activity reflects primarily the failure to separate sharply the question what activities it is appropriate for government to finance from the question what activities it is appropriate for government to administer — a distinction that is important in other areas of government activity as well. Because the financing of general education by government is widely accepted, the provision of general education directly by governmental bodies has also been accepted. But institutions that provide general education are especially well suited also to provide some kinds of vocational and professional education, so the acceptance of direct government provision of general education has led to the direct provision of vocational education. To complete the circle, the provision of vocational education has, in turn, meant that it too was financed by government, since financing has been predominantly of educational institutions not of particular kinds of educational services.

The alternative arrangements whose broad outlines are sketched in this paper distinguish sharply between the financing of education and the operation of educational institutions, and between education for citizenship or leadership and for greater economic productivity. Throughout, they center attention on the person rather than the institution. Government, preferably local governmental units, would give each child, through his parents, a specified sum to be used solely in paying for his general education; the parents would be free to spend this sum at a school of their own choice, provided it met certain minimum standards laid down by the appropriate governmental unit. Such schools would be conducted under a variety of auspices: by private enterprises operated for profit, nonprofit institutions established by private endowment, religious bodies, and some even by governmental units.

For vocational education, the government, this time however the central government, might likewise deal directly with the individual seeking such education. If it did so, it would make funds available to him to finance his education, not as a subsidy but as “equity” capital. In return, he would obligate himself to pay the state a specified fraction of his earnings above some minimum, the fraction and minimum being determined to make the program self-financing. Such a program would eliminate existing imperfections in the capital market and so widen the opportunity of individuals to make productive investments in themselves while at the same time assuring that the costs are borne by those who benefit most directly rather than by the population at large.

An alternative, and a highly desirable one if it is feasible, is to stimulate private arrangements directed toward the same end. The result of these measures would be a sizable reduction in the direct activities of government, yet a great widening in the educational opportunities open to our children. They would bring a healthy increase in the variety of educational institutions available and in competition among them. Private initiative and enterprise would quicken the pace of progress in this area as it has in so many others. Government would serve its proper function of improving the operation of the invisible hand without substituting the dead hand of bureaucracy.

Note: I am indebted to P. T. Bauer, A. R. Prest, and H. G. Johnson for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

1. It is by no means so fantastic as may at first appear that such a step would noticeably affect the size of families. For example. one explanation of the lower birth rate among higher than among lower socio-economic groups may well be that children are relatively more expensive to the former, thanks in considerable measure to the higher standards of education they maintain and the costs of which they bear.

2. Essentially this proposal — public financing but private operation of education has recently been suggested in several southern states as a means of evading the Supreme Court ruling against segregation. This fact came to my attention after this paper was essentially in its present form. My initial reaction — and I venture to predict, that of most readers — was that this possible use of the proposal was a count against it, that it was a particularly striking case of the possible defect — the exacerbating of class distinctions — referred to in the second paragraph preceding the one to which this note is attached.

Further thought has led me to reverse my initial reaction. Principles can be tested most clearly by extreme cases. Willingness to permit free speech to people with whom one agrees is hardly evidence of devotion to the principle of free speech; the relevant test is willingness to permit free speech to people with whom one thoroughly disagrees. Similarly, the relevant test of the belief in individual freedom is the willingness to oppose state intervention even when it is designed to prevent individual activity of a kind one thoroughly dislikes. I deplore segregation and racial prejudice; pursuant to the principles set forth at the outset of the paper, it is clearly an appropriate function of the state to prevent the use of violence and physical coercion by one group on another; equally clearly, it is not an appropriate function of the state to try to force individuals to act in accordance with my — or anyone else’s views, whether about racial prejudice or the party to vote for, so long as the action of anyone individual affects mostly himself. These are the grounds on which I oppose the proposed Fair Employment Practices Commissions; and they lead me equally to oppose forced nonsegregation. However, the same grounds also lead me to oppose forced segregation. Yet, so long as the schools are publicly operated, the only choice is between forced nonsegregation and forced segregation; and if I must choose between these evils, I would choose the former as the lesser.

The fact that I must make this choice is a reflection of the basic weakness of a publicly operated school system. Privately conducted schools can resolve the dilemma. They make unnecessary either choice. Under such a system, there can develop exclusively white schools, exclusively colored schools, and mixed schools. Parents can choose which to send their children to. The appropriate activity for those who oppose segregation and racial prejudice is to try to persuade others of their views; if and as they succeed, the mixed schools will grow at the expense of the nonmixed, and a gradual transition will take place. So long as the school system is publicly operated, only drastic change is possible; one must go from one extreme to the other; it is a great virtue of the private arrangement that it permits a gradual transition.

An example that comes to mind as illustrating the preceding argument is summer camps for children. Is there any objection to the simultaneous existence of some camps that are wholly Jewish, some wholly non-Jewish, and some mixed? One can — though many who would react quite differently to negro-white segregation — would not explore the existence of attitudes that lead to the three types; one can seek to propagate views that would tend to the growth of the mixed school at the expense of the extremes; but is it an appropriate function of the state to prohibit the unmixed camps?

The establishment of private schools does not of itself guarantee the desirable freedom of choice on the part of parents. The public funds could be made available subject to the condition that parents use them solely in segregated schools; and it may be that some such condition is contained in the proposals now under consideration by southern states. Similarly, the public funds could be made available for use solely in nonsegregated schools. The proposed plan is not therefore inconsistent with either forced segregation or forced nonsegregation. The point is that it makes available a third alternative.

3. See George J. Stigler. Employment and Compensation in Education, (National Bureau of Economic Research, Occasional Paper 1111, 1950). p. 1111.

4. The subsidizing of basic research for example. I have interpreted education narrowly so as to exclude considerations of this type which would open up an unduly wide field.

5. The increased return may be only partly in a monetary form; it may also consist of non-pecuniary advantages attached to the occupation for which the vocational training fits the individual. Similarly, the occupation may have nonpecuniary disadvantages, which would have to be reckoned among the costs of the investment.

6. For a more detailed and precise statement of the considerations entering into the choice of an occupation, see Milton Friedman and Simon Kuznets, Income from Independent Professional Practice, (National Bureau of Economic Research, N.Y., 1945). pp. 81-94, 118-37.

7. Ibid., pp. 68-69. 84. 148-51.

8. Ibid., pp. 88-94.

9. Education and Economic Well-Being in American Democracy , (Educational Policies Commission, National Education Association of United States and American Association of School Administrators, 1940).

10. Despite these obstacles to fixed money loans, I am told that they have been a very common means of financing university education in Sweden, where they have apparently been available at moderate rates of interest. Presumably a proximate explanation is a smaller dispersion of income among university graduates than in the United States. But this is no ultimate explanation and may not be the only or major reason for the difference in practice. Further study of Swedish and similar experience is highly desirable to test whether the reasons given above are adequate to explain the absence in the United States and other countries of a highly developed market in loans to finance vocational education, or whether there may not be other obstacles that could be removed more easily.

11. It is amusing to speculate on how the business could be done and on some ancillary methods of profiting from it. The initial entrants would be able to choose the very best investments, by imposing very high quality standards on the individuals they were willing to finance. If they did so, they could increase the profitability of their investment by getting public recognition of the superior quality of the individuals they financed: the legend, “Training financed by XYZ Insurance Company” could be made into an assurance of quality (like “Approved by Good Housekeeping”) that would attract custom. All sorts of other common services might be rendered by the XYZ company to “its” physicians, lawyers, dentists, and so on.

12. The point in question is familiar in connection with the disincentive effects of income taxation. An example that perhaps makes this clearer than the example in the text is to suppose that the individual can earn $5, say, by some extra work and would just be willing to do so if he could keep the whole $5 — that is, he values the non-pecuniary costs of the extra worth at just under $5. If x is say 0.10, he only keeps $4.50 and this will not be enough to induce him to do the extra work. It should be noted that a plan involving fixed money loans to individuals might be less seriously affected by differences among various uses of skills in non-pecuniary returns and costs than the plan for equity investment under consideration. It would not however be unaffected by them; such differences would tend to produce different frequencies of default depending on the use made of the skill and so unduly favor uses yielding relatively high non-pecuniary returns or involving relatively low non-pecuniary costs. I am indebted to Harry G. Johnson and Paul W. Cook, Jr., for suggesting the inclusion of this qualification. For a fuller discussion of the role of non-pecuniary advantages and disadvantages in determining earnings in different pursuits. See Friedman and Kuznets, loc. cit.

RECEIVE EDUCATIONAL CHOICE UPDATES STRAIGHT TO YOUR INBOX

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- © 2024 EdChoice

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Education Public School

Public School vs. Private School: Argumentative Comparison

Table of contents, public schools: accessibility and diversity, public schools: limited resources and class sizes, private schools: specialized curriculum and resources, private schools: affordability and socioeconomic disparities.

- Baker, B. D., & Welner, K. G. (Eds.). (2017). School Choice: Policies and Outcomes. University of California Press.

- Henig, J. R., Hula, R. C., & Orr, M. T. (Eds.). (2019). Educational Inequality and School Finance: Why Money Matters for America's Students. Harvard Education Press.

- Kahlenberg, R. D. (Ed.). (2013). The Future of School Integration: Socioeconomic Diversity as an Education Reform Strategy. Century Foundation Press.

- Ravitch, D. (2013). Reign of Error: The Hoax of the Privatization Movement and the Danger to America's Public Schools. Knopf.

- Van Dunk, D. D., & Taylor, S. S. (Eds.). (2020). Global Perspectives on School Choice and Privatization. Information Age Publishing.

*minimum deadline

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below

- Student Life

- Plans After High School

- Interpretation

Related Essays

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

Public School vs Private School Essay

Public school vs private school essay introduction, private schools vs public schools: classroom size & admission, cost & tuition.

Need to compare and contrast public and private schools? Essay samples like this one will help you with this task! Here, you will learn about advantages, disadvantages, and differences between public schools vs private schools. Choose your side of the debate and persuade the readers in your public school vs private school essay!

Comparing private and public schools can be more or less like comparing oranges and apples, two very disparate things that can never be held on similar standards. Choosing the best school for your child is one of the most important decisions parents have to make for their children but most parents rely on rumors and hearsay in deciding on whether to send their children to a private or a public school.

The best ways to determine whether you are making the right decision for your child is by visiting the school and asking for clarification from teachers for all your queries. What school your youngster attend to is a personal decision which is greatly determined by the family values, special needs of the kids, his mannerisms and interests.

This essay critically compares the differences and similarities, advantages and disadvantages and the issues that a rise in both private and public schools that affects the education of the children mainly preschool kids the its effects they on the kids future life.

Statistics show that some time back private school used to do better than public schools but recently this gap has been narrowing and making it harder for parents to choose between a private independent school with a high price tag on it, from a local public school which is relatively cheaper (Diana, 2006).

According to Maureen ( 2011, pp.10) public schools usually have larger class sizes due to the fact that they are required to admit every child who meets the qualifications set by the government. This offers an advantage to the pre-school children by improving their communication and socializing skills since they interact with more children from different races, cultures and social classes.

However, large classes are also disadvantageous in that it reduces the ratio of teachers to students and this tends to limit the teacher’s concentration on students hence limiting the children’s there performance. The average ratio of teachers to students in public schools is 1:17while in private schools its 1:9.

Private schools on the other hand are very selective in terms of their admissions. Some schools cannot admit students from certain religions, races or even economic status. This tends to reduce the population of private schools. Some of the long term effects to children attending privately owned pre-schools are poor socializing skills due to the low population size and similar social classes, religion and lack of diverse cultures (Robert, 2011, pp4).

Public schools are cheaper and they are funded by the government and some of them are usually underfunded. They are a part of the large school system which is part of the government and this makes them vulnerable to the political influence hence exposes them to political vulnerabilities which if experienced affects their performance.

The economic status of the country and the government also greatly affects the operations of public schools. Their curriculum is determined by the government and as you know different regions face different challenges hence the need for different curriculum to meet the different needs. (GreatSchools, 2010, pp.5)

Private schools on the other hand charge a higher tuition fee which is the major source of its funds. This makes them independent and protects them from the political realm hence they are free to determine their own curricula which is usually single minded, producing best results by providing the best quality of education possible (Eddie , 2011, pp.4)

In cases of children with special needs public schools usually have special programs and specially trained teachers who are well trained to work with such children. In contrast most private schools lack these programs and they are sometimes forced to deny such kids admission to their institutions and sometimes these services may be offered at an extra cost.

Is the question about which schools are better, private or public schools, answered yet? I bet not since there are no clear conclusions since they both have advantages and disadvantages as we have seen. In a nut shell the best school for ones child depends on the values, mannerisms, family, back ground, needs and interests of both the parents and the children. In other words one man’s meat is another man’s poison.

Diana, J. S. (2006). Public Schools Perform Near Private Ones in Study . Web.

Eddie, R. (2011). Pre School Education: Private Schools Vs PublicSchools . Web.

Great Schools Staff. (2010). Private versus public . Web.

Maureen, B. (2011). Public vs. private : Which is right for your child? Web.

Robert, N. (2011). Private vs Public Schools: Class Size. Web.

- Self-Management: Becoming an Independent Learner

- Why Dismissing Community Colleges Is a Bad Idea

- Tuition Reimbursement Program

- Should College Tuition Be Free: University Education

- Adam Davidson: Is College Tuition Really Too High

- Reasons for attending college

- Should Higher Education be Free?

- Majoring in Software Engineering

- College Degree: Does It Matter?

- Higher Education an Element to Success

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, December 27). Public School vs Private School. https://ivypanda.com/essays/public-schools-vs-private-schools/

"Public School vs Private School." IvyPanda , 27 Dec. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/public-schools-vs-private-schools/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Public School vs Private School'. 27 December.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Public School vs Private School." December 27, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/public-schools-vs-private-schools/.

1. IvyPanda . "Public School vs Private School." December 27, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/public-schools-vs-private-schools/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Public School vs Private School." December 27, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/public-schools-vs-private-schools/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

When it Comes to Education, the Federal Government is in Charge of ... Um, What?

- Posted August 29, 2017

- By Brendan Pelsue

Judging by her Senate confirmation process, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos is one of the most controversial members of President Donald Trump’s cabinet. She was the only nominee to receive two “no” votes from members of her own party, Senators Susan Collins of Maine and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska. On the eve of her confirmation vote, Democrats staged an all-night vigil in which they denounced her from the Senate floor. Following a 50–50 vote, Vice President Mike Pence was summoned in his capacity as president of the Senate to break the tie for DeVos — a first in the Senate’s 228-year history of giving “advice and consent” to presidential cabinet nominees.

Now that DeVos is several months into her tenure as the 11th secretary of education, both her supporters and detractors are paying close attention to the policies she is beginning to implement and how they will change the nation’s public schools. Even for veteran education watchers, however, this is difficult, not only because the Trump administration’s budget and policy proposals are more skeletal than those put forward by previous administrations, but because the Department of Education does not directly oversee the nation’s 100,000 public schools. States have some oversight, but individual municipalities, are, in most cases, the legal entities responsible for running schools and for providing the large majority of funding through local tax dollars.

Still, the federal government uses a complex system of funding mechanisms, policy directives, and the soft but considerable power of the presidential bully pulpit to shape what, how, and where students learn. Anyone hoping to understand the impact of DeVos’ tenure as secretary of education first needs to grasp some core basics: what the federal government controls, how it controls it, and how that balance does (and doesn’t) change from administration to administration.

This policy landscape is the subject of an Ed School course, A-129, The Federal Government and Schools, taught by Lecturer Laura Schifter , Ed.M.'07, Ed.D.'14,, a former senior adviser to Congressman George Miller (D-CA). Schifter has noticed that even for students who have worked in public schools, understanding the federal government’s current role in education can be complicated.

“Students frequently need a refresher on things like understanding the nature of the relationship between the federal government and the states, and what federalism is,” she says. With that in mind, the course begins with a civics review, especially the complicated politics of federalism, then moves on to a history lesson in federal education legislation since the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, and finally to an overview of the actual policy mechanisms through which the federal government enforces and implements the law. Throughout, students “read statutes, they read regulations, they read court decisions,” Schifter says — activities she believes are essential since there is no better way for educators to understand the law than to consult it themselves.

The civics and history lessons required to understand the federal government’s role in education are of course deeply intertwined and begin, as with so many things American, with the Constitution. That document makes no mention of education. It does state in the 10th Amendment that “the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution … are reserved to the States respectively.” This might seem to preclude any federal oversight of education, except that the 14th Amendment requires all states to provide “any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”